Lambda phage

This article provides insufficient context for those unfamiliar with the subject. (September 2013) |

| Escherichia virus Lambda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Electron micrograph of a virus particle of species Escherichia virus Lambda | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Duplodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Heunggongvirae |

| Phylum: | Uroviricota |

| Class: | Caudoviricetes |

| Order: | Caudovirales |

| Family: | Siphoviridae |

| Genus: | Lambdavirus |

| Species: | Escherichia virus Lambda

|

Enterobacteria phage λ (lambda phage, coliphage λ, officially Escherichia virus Lambda) is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species Escherichia coli (E. coli). It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950.[2] The wild type of this virus has a temperate life cycle that allows it to either reside within the genome of its host through lysogeny or enter into a lytic phase, during which it kills and lyses the cell to produce offspring. Lambda strains, mutated at specific sites, are unable to lysogenize cells; instead, they grow and enter the lytic cycle after superinfecting an already lysogenized cell.[3]

The phage particle consists of a head (also known as a capsid),[4] a tail, and tail fibers (see image of virus below). The head contains the phage's double-strand linear DNA genome. During infections, the phage particle recognizes and binds to its host, E. coli, causing DNA in the head of the phage to be ejected through the tail into the cytoplasm of the bacterial cell. Usually, a "lytic cycle" ensues, where the lambda DNA is replicated and new phage particles are produced within the cell. This is followed by cell lysis, releasing the cell contents, including virions that have been assembled, into the environment. However, under certain conditions, the phage DNA may integrate itself into the host cell chromosome in the lysogenic pathway. In this state, the λ DNA is called a prophage and stays resident within the host's genome without apparent harm to the host. The host is termed a lysogen when a prophage is present. This prophage may enter the lytic cycle when the lysogen enters a stressed condition.

Anatomy

The virus particle consists of a head and a tail that can have tail fibers. The whole particle consists of 12–14 different proteins with more than 1000 protein molecules total and one DNA molecule located in the phage head. However, it is still not entirely clear whether the L and M proteins are part of the virion.[5] All characterized lambdoid phages possess an N protein-mediated transcription antitermination mechanism, with the exception of phage HK022.[6]

The genome contains 48,502[7] base pairs of double-stranded, linear DNA, with 12-base single-strand segments at both 5' ends.[8] These two single-stranded segments are the "sticky ends" of what is called the cos site. The cos site circularizes the DNA in the host cytoplasm. In its circular form, the phage genome, therefore, is 48,502 base pairs in length.[8] The lambda genome can be inserted into the E. coli chromosome and is then called a prophage. See section below for details.

The tail of lambda phages is made of at least 6 proteins (H, J, U, V, Stf, Tfa) and requires 7 more for assembly (I, K, L, M, Z, G/T). This assembly process begins with protein J, which then recruits proteins I, L, K, and G/T to add protein H. Once G and G/T leave the complex, protein V can assemble onto the J/H scaffold. Then, protein U is added to the head-proximal end of the tail. Protein Z is able to connect the tail to the head. Protein H is cleaved due to the actions of proteins U and Z.[5]

Life cycle

Infection

Lambda phage is a non-contractile tailed phage, meaning during an infection event it cannot 'force' its DNA through a bacterial cell membrane. It must instead use an existing pathway to invade the host cell, having evolved the tip of its tail to interact with a specific pore to allow entry of its DNA to the hosts.

- Bacteriophage Lambda binds to an E. coli cell by means of its J protein in the tail tip. The J protein interacts with the maltose outer membrane porin (the product of the lamB gene) of E. coli,[9] a porin molecule, which is part of the maltose operon.

- The linear phage genome is injected through the outer membrane.

- The DNA passes through the mannose permease complex in the inner membrane[10][11] (encoded by the manXYZ genes) and immediately circularises using the cos sites, 12-base G-C-rich cohesive "sticky ends". The single-strand viral DNA ends are ligated by host DNA ligase. It is not generally appreciated that the 12 bp lambda cohesive ends were the subject of the first direct nucleotide sequencing of a biological DNA.[6]

- Host DNA gyrase puts negative supercoils in the circular chromosome, causing A-T-rich regions to unwind and drive transcription.

- Transcription starts from the constitutive PL, PR and PR' promoters producing the 'immediate early' transcripts. At first, these express the N and cro genes, producing N, Cro and a short inactive protein.

- Cro binds to OR3, preventing access to the PRM promoter, preventing expression of the cI gene. N binds to the two Nut (N utilisation) sites, one in the N gene in the PL reading frame, and one in the cro gene in the PR reading frame.

- The N protein is an antiterminator, and functions by engaging the transcribing RNA polymerase at specific sites of the nascently transcribed mRNA. When RNA polymerase transcribes these regions, it recruits N and forms a complex with several host Nus proteins. This complex skips through most termination sequences. The extended transcripts (the 'late early' transcripts) include the N and cro genes along with cII and cIII genes, and xis, int, O, P and Q genes discussed later.

- The cIII protein acts to protect the cII protein from proteolysis by FtsH (a membrane-bound essential E. coli protease) by acting as a competitive inhibitor. This inhibition can induce a bacteriostatic state, which favours lysogeny. cIII also directly stabilises the cII protein.[12]

On initial infection, the stability of cII determines the lifestyle of the phage; stable cII will lead to the lysogenic pathway, whereas if cII is degraded the phage will go into the lytic pathway. Low temperature, starvation of the cells and high multiplicity of infection (MOI) are known to favor lysogeny (see later discussion).[13]

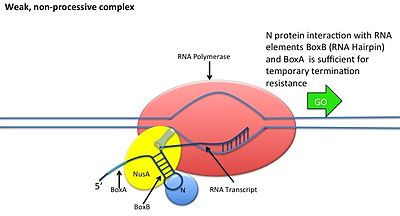

N antitermination

This occurs without the N protein interacting with the DNA; the protein instead binds to the freshly transcribed mRNA. Nut sites contain 3 conserved "boxes", of which only BoxB is essential.

- The boxB RNA sequences are located close to the 5' end of the pL and pR transcripts. When transcribed, each sequence forms a hairpin loop structure that the N protein can bind to.

- N protein binds to boxB in each transcript, and contacts the transcribing RNA polymerase via RNA looping. The N-RNAP complex is stabilized by subsequent binding of several host Nus (N utilisation substance) proteins (which include transcription termination/antitermination factors and, bizarrely, a ribosome subunit).

- The entire complex (including the bound Nut site on the mRNA) continues transcription, and can skip through termination sequences.

Lytic life cycle

This is the lifecycle that the phage follows following most infections, where the cII protein does not reach a high enough concentration due to degradation, so does not activate its promoters.[citation needed]

- The 'late early' transcripts continue being written, including xis, int, Q and genes for replication of the lambda genome (OP). Cro dominates the repressor site (see "Repressor" section), repressing synthesis from the PRM promoter (which is a promoter of the lysogenic cycle).

- The O and P proteins initiate replication of the phage chromosome (see "Lytic Replication").

- Q, another antiterminator, binds to Qut sites.

- Transcription from the PR' promoter can now extend to produce mRNA for the lysis and the head and tail proteins.

- Structural proteins and phage genomes self-assemble into new phage particles.

- Products of the genes S,R, Rz and Rz1 cause cell lysis. S is a holin, a small membrane protein that, at a time determined by the sequence of the protein, suddenly makes holes in the membrane. R is an endolysin, an enzyme that escapes through the S holes and cleaves the cell wall. Rz and Rz1 are membrane proteins that form a complex that somehow destroys the outer membrane, after the endolysin has degraded the cell wall. For wild-type lambda, lysis occurs at about 50 minutes after the start of infection and releases around 100 virions.

Rightward transcription

Rightward transcription expresses the O, P and Q genes. O and P are responsible for initiating replication, and Q is another antiterminator that allows the expression of head, tail, and lysis genes from PR’.[6]

Pr is the promoter for rightward transcription, and the cro gene is a regulator gene. The cro gene will encode for the Cro protein that will then repress Prm promoter. Once Pr transcription is underway the Q gene will then be transcribed at the far end of the operon for rightward transcription. The Q gene is a regulator gene found on this operon, which will control the expression of later genes for rightward transcription. Once the gene's regulatory proteins allow for expression, the Q protein will then act as an anti-terminator. This will then allow for the rest of the operon to be read through until it reaches the transcription terminator. Thus allowing expression of later genes in the operon, and leading to the expression of the lytic cycle.[15]

Pr promoter has been found to activate the origin in the use of rightward transcription, but the whole picture of this is still somewhat misunderstood. Given there are some caveats to this, for instance this process is different for other phages such as N15 phage, which may encode for DNA polymerase. Another example is the P22 phage may replace the p gene, which encodes for an essential replication protein for something that is capable of encoding for a DnaB helices.[6]

Lytic replication

- For the first few replication cycles, the lambda genome undergoes θ replication (circle-to-circle).

- This is initiated at the ori site located in the O gene. O protein binds the ori site, and P protein binds the DnaB subunit of the host replication machinery as well as binding O. This effectively commandeers the host DNA polymerase.

- Soon, the phage switches to a rolling circle replication similar to that used by phage M13. The DNA is nicked and the 3’ end serves as a primer. Note that this does not release single copies of the phage genome but rather one long molecule with many copies of the genome: a concatemer.

- These concatemers are cleaved at their cos sites as they are packaged. Packaging cannot occur from circular phage DNA, only from concatomeric DNA.

Q antitermination

Q is similar to N in its effect: Q binds to RNA polymerase in Qut sites and the resulting complex can ignore terminators, however the mechanism is very different; the Q protein first associates with a DNA sequence rather than an mRNA sequence.[16]

- The Qut site is very close to the PR’ promoter, close enough that the σ factor has not been released from the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Part of the Qut site resembles the -10 Pribnow box, causing the holoenzyme to pause.

- Q protein then binds and displaces part of the σ factor and transcription re-initiates.

- The head and tail genes are transcribed and the corresponding proteins self-assemble.

Leftward transcription

Leftward transcription expresses the gam, xis, bar and int genes.[6] Gam proteins are involved in recombination. Gam is also important in that it inhibits the host RecBCD nuclease from degrading the 3’ ends in rolling circle replication. Int and xis are integration and excision proteins vital to lysogeny.[citation needed]

Leftward transcription process

- Lambda phage inserts chromosome into the cytoplasm of the host bacterial cell.

- The phage chromosome is inserted to the host bacterial chromosome through DNA ligase.

- Transcription of the phage chromosome proceeds leftward when the host RNA polymerase attaches to promotor site pL resulting in the translation of gene N.

- Gene N acts a regulatory gene that results in RNA polymerase being unable to recognize translation-termination sites.[17]

Leftward Transcription mutations

Leftward transcription is believed to result in a deletion mutation of the rap gene resulting in a lack of growth of lambda phage. This is due to RNA polymerase attaching to pL promoter site instead of the pR promotor site. Leftward transcription results in barI and barII transcription on the left operon. Bar positive phenotype is present when the rap gene is absent. The lack of growth of lambda phage is believed to occur due to a temperature sensitivity resulting in inhibition of growth.[18]

xis and int regulation of insertion and excision

- xis and int are found on the same piece of mRNA, so approximately equal concentrations of xis and int proteins are produced. This results (initially) in the excision of any inserted genomes from the host genome.

- The mRNA from the PL promoter forms a stable secondary structure with a stem-loop in the sib section of the mRNA. This targets the 3' (sib) end of the mRNA for RNAaseIII degradation, which results in a lower effective concentration of int mRNA than xis mRNA (as the int cistron is nearer to the sib sequence than the xis cistron is to the sib sequence), so a higher concentrations of xis than int is observed.

- Higher concentrations of xis than int result in no insertion or excision of phage genomes, the evolutionarily favoured action - leaving any pre-inserted phage genomes inserted (so reducing competition) and preventing the insertion of the phage genome into the genome of a doomed host.

Lysogenic (or lysenogenic) life cycle

The lysogenic lifecycle begins once the cI protein reaches a high enough concentration to activate its promoters, after a small number of infections.

- The 'late early' transcripts continue being written, including xis, int, Q and genes for replication of the lambda genome.

- The stabilized cII acts to promote transcription from the PRE, PI and Pantiq promoters.

- The Pantiq promoter produces antisense mRNA to the Q gene message of the PR promoter transcript, thereby switching off Q production. The PRE promoter produces antisense mRNA to the cro section of the PR promoter transcript, turning down cro production, and has a transcript of the cI gene. This is expressed, turning on cI repressor production. The PI promoter expresses the int gene, resulting in high concentrations of Int protein. This int protein integrates the phage DNA into the host chromosome (see "Prophage Integration").

- No Q results in no extension of the PR' promoter's reading frame, so no lytic or structural proteins are made. Elevated levels of int (much higher than that of xis) result in the insertion of the lambda genome into the hosts genome (see diagram). Production of cI leads to the binding of cI to the OR1 and OR2 sites in the PR promoter, turning off cro and other early gene expression. cI also binds to the PL promoter, turning off transcription there too.

- Lack of cro leaves the OR3 site unbound, so transcription from the PRM promoter may occur, maintaining levels of cI.

- Lack of transcription from the PL and PR promoters leads to no further production of cII and cIII.

- As cII and cIII concentrations decrease, transcription from the Pantiq, PRE and PI stop being promoted since they are no longer needed.

- Only the PRM and PR' promoters are left active, the former producing cI protein and the latter a short inactive transcript. The genome remains inserted into the host genome in a dormant state.

The prophage is duplicated with every subsequent cell division of the host. The phage genes expressed in this dormant state code for proteins that repress expression of other phage genes (such as the structural and lysis genes) in order to prevent entry into the lytic cycle. These repressive proteins are broken down when the host cell is under stress, resulting in the expression of the repressed phage genes. Stress can be from starvation, poisons (like antibiotics), or other factors that can damage or destroy the host. In response to stress, the activated prophage is excised from the DNA of the host cell by one of the newly expressed gene products and enters its lytic pathway.

Prophage integration

The integration of phage λ takes place at a special attachment site in the bacterial and phage genomes, called attλ. The sequence of the bacterial att site is called attB, between the gal and bio operons, and consists of the parts B-O-B', whereas the complementary sequence in the circular phage genome is called attP and consists of the parts P-O-P'. The integration itself is a sequential exchange (see genetic recombination) via a Holliday junction and requires both the phage protein Int and the bacterial protein IHF (integration host factor). Both Int and IHF bind to attP and form an intasome, a DNA-protein-complex designed for site-specific recombination of the phage and host DNA. The original B-O-B' sequence is changed by the integration to B-O-P'-phage DNA-P-O-B'. The phage DNA is now part of the host's genome.[19]

Maintenance of lysogeny

- Lysogeny is maintained solely by cI. cI represses transcription from PL and PR while upregulating and controlling its own expression from PRM. It is therefore the only protein expressed by lysogenic phage.

- This is coordinated by the PL and PR operators. Both operators have three binding sites for cI: OL1, OL2, and OL3 for PL, and OR1, OR2 and OR3 for PR.

- cI binds most favorably to OR1; binding here inhibits transcription from PR. As cI easily dimerises, the binding of cI to OR1 greatly increases the affinity of the binding of cI to OR2, and this happens almost immediately after OR1 binding. This activates transcription in the other direction from PRM, as the N terminal domain of cI on OR2 tightens the binding of RNA polymerase to PRM and hence cI stimulates its own transcription. When it is present at a much higher concentration, it also binds to OR3, inhibiting transcription from PRM, thus regulating its own levels in a negative feedback loop.

- cI binding to the PL operator is very similar, except that it has no direct effect on cI transcription. As an additional repression of its own expression, however, cI dimers bound to OR3 and OL3 bend the DNA between them to tetramerise.

- The presence of cI causes immunity to superinfection by other lambda phages, as it will inhibit their PL and PR promoters.

Induction

The classic induction of a lysogen involved irradiating the infected cells with UV light. Any situation where a lysogen undergoes DNA damage or the SOS response of the host is otherwise stimulated leads to induction.

- The host cell, containing a dormant phage genome, experiences DNA damage due to a high stress environment, and starts to undergo the SOS response.

- RecA (a cellular protein) detects DNA damage and becomes activated. It is now RecA*, a highly specific co-protease.

- Normally RecA* binds LexA (a transcription repressor), activating LexA auto-protease activity, which destroys LexA repressor, allowing production of DNA repair proteins. In lysogenic cells, this response is hijacked, and RecA* stimulates cI autocleavage. This is because cI mimics the structure of LexA at the autocleavage site.

- Cleaved cI can no longer dimerise, and loses its affinity for DNA binding.

- The PR and PL promoters are no longer repressed and switch on, and the cell returns to the lytic sequence of expression events (note that cII is not stable in cells undergoing the SOS response). There is however one notable difference.

Control of phage genome excision in induction

- The phage genome is still inserted in the host genome and needs excision for DNA replication to occur. The sib section beyond the normal PL promoter transcript is, however, no longer included in this reading frame (see diagram).

- No sib domain on the PL promoter mRNA results in no hairpin loop on the 3' end, and the transcript is no longer targeted for RNAaseIII degradation.

- The new intact transcript has one copy of both xis and int, so approximately equal concentrations of xis and int proteins are produced.

- Equal concentrations of xis and int result in the excision of the inserted genome from the host genome for replication and later phage production.

Multiplicity reactivation and prophage reactivation

Multiplicity reactivation (MR) is the process by which multiple viral genomes, each containing inactivating genome damage, interact within an infected cell to form a viable viral genome. MR was originally discovered with phage T4, but was subsequently found in phage λ (as well as in numerous other bacterial and mammalian viruses[20]). MR of phage λ inactivated by UV light depends on the recombination function of either the host or of the infecting phage.[21] Absence of both recombination systems leads to a loss of MR.

Survival of UV-irradiated phage λ is increased when the E. coli host is lysogenic for an homologous prophage, a phenomenon termed prophage reactivation.[22] Prophage reactivation in phage λ appears to occur by a recombinational repair process similar to that of MR.

Repressor

The repressor found in the phage lambda is a notable example of the level of control possible over gene expression by a very simple system. It forms a 'binary switch' with two genes under mutually exclusive expression, as discovered by Barbara J. Meyer.[23]

The lambda repressor gene system consists of (from left to right on the chromosome):

- cI gene

- OR3

- OR2

- OR1

- cro gene

The lambda repressor is a self assembling dimer also known as the cI protein.[24] It binds DNA in the helix-turn-helix binding motif. It regulates the transcription of the cI protein and the Cro protein.

The life cycle of lambda phages is controlled by cI and Cro proteins. The lambda phage will remain in the lysogenic state if cI proteins predominate, but will be transformed into the lytic cycle if cro proteins predominate.

The cI dimer may bind to any of three operators, OR1, OR2, and OR3, in the order OR1 > OR2 > OR3. Binding of a cI dimer to OR1 enhances binding of a second cI dimer to OR2, an effect called cooperativity. Thus, OR1 and OR2 are almost always simultaneously occupied by cI. However, this does not increase the affinity between cI and OR3, which will be occupied only when the cI concentration is high.

At high concentrations of cI, the dimers will also bind to operators OL1 and OL2 (which are over 2 kb downstream from the R operators). When cI dimers are bound to OL1, OL2, OR1, and OR2 a loop is induced in the DNA, allowing these dimers to bind together to form an octamer. This is a phenomenon called long-range cooperativity. Upon formation of the octamer, cI dimers may cooperatively bind to OL3 and OR3, repressing transcription of cI. This autonegative regulation ensures a stable minimum concentration of the repressor molecule and, should SOS signals arise, allows for more efficient prophage induction.[25]

- In the absence of cI proteins, the cro gene may be transcribed.

- In the presence of cI proteins, only the cI gene may be transcribed.

- At high concentration of cI, transcriptions of both genes are repressed.

-

Some base pairs with serve a dual function with promoter and operator for either cl and cro proteins.

-

Protein cl turned ON, with repressor bound to OR2 polymerase binding is increased and turn OFF OR1.

-

Lysogen repression all 3 sites bound is a low occurrence due to OR3 weak binding affinity. OR1 repression increases binding affinity to OR2 due to repressor-repressor interaction. Increased concentrations of repressor increase binding.

Protein function overview

| Protein | Function in life cycle | Promoter region | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| cIII | Regulatory protein CIII. Lysogeny, cII Stability | PL | (Clear 3) HflB (FtsH) binding protein, protects cII from degradation by proteases. |

| cII | Lysogeny, Transcription activator | PR | (Clear 2) Activates transcription from the PAQ, PRE and PI promoters, transcribing cI and int. Low stability due to susceptibility to cellular HflB (FtsH) proteases (especially in healthy cells and cells undergoing the SOS response). High levels of cII will push the phage toward integration and lysogeny while low levels of cII will result in lysis. |

| cI | Repressor, Maintenance of Lysogeny | PRM, PRE | (Clear 1) Transcription inhibitor, binds OR1, OR2 and OR3 (affinity OR1 > OR2 = OR3, i.e. preferentially binds OR1). At low concentrations blocks the PR promoter (preventing cro production). At high concentrations downregulates its own production through OR3 binding. Repressor also inhibits transcription from the PL promoter. Susceptible to cleavage by RecA* in cells undergoing the SOS response. |

| cro | Lysis, Control of Repressor's Operator | PR | Transcription inhibitor, binds OR3, OR2 and OR1 (affinity OR3 > OR2 = OR1, i.e. preferentially binds OR3). At low concentrations blocks the pRM promoter (preventing cI production). At high concentrations downregulates its own production through OR2 and OR1 binding. No cooperative binding (c.f. below for cI binding) |

| O | Lysis, DNA replication | PR | Replication protein O. Initiates Phage Lambda DNA replication by binding at ori site. |

| P | Lysis, DNA Replication | PR | Initiates Phage Lambda DNA replication by binding to O and DnaB subunit. These bindings provide control over the host DNA polymerase. |

| gam | Lysis, DNA replication | PL | Inhibits host RecBCD nuclease from degrading 3' ends—allow rolling circle replication to proceed. |

| S | Lysis | PR' | Holin, a membrane protein that perforates the membrane during lysis. |

| R | Lysis | PR' | Endolysin, Lysozyme, an enzyme that exits the cell through the holes produced by Holin and cleaves apart the cell wall. |

| Rz and Rz1 | Lysis | PR' | Forms a membrane protein complex that destroys the outer cell membrane following the cell wall degradation by endolysin. Spanin, Rz1(outer membrane subunit) and Rz(inner membrane subunit). |

| F | Lysis | PR' | Phage capsid head proteins. |

| D | Lysis | PR' | Head decoration protein. |

| E | Lysis | PR' | Major head protein. |

| C | Lysis | PR' | Minor capsid protein. |

| B | Lysis | PR' | Portal protein B. |

| A | Lysis | PR' | Large terminase protein. |

| J | Lysis | PR' | Host specificity protein J. |

| M V U G L T Z | Lysis | PR' | Minor tail protein M. |

| K | Lysis | PR' | Probable endopeptidase. |

| H | Lysis | PR' | Tail tape measure protein H. |

| I | Lysis | PR' | Tail assembly protein I. |

| FI | Lysis | PR' | DNA-packing protein FI. |

| FII | Lysis | PR' | Tail attachment protein. |

| tfa | Lysis | PR' | Tail fiber assembly protein. |

| int | Genome Integration, Excision | PI, PL | Integrase, manages insertion of phage genome into the host's genome. In Conditions of low int concentration there is no effect. If xis is low in concentration and int high then this leads to the insertion of the phage genome. If xis and int have high (and approximately equal) concentrations this leads to the excision of phage genomes from the host's genome. |

| xis | Genome Excision | PI, PL | Excisionase and int protein regulator, manages excision and insertion of phage genome into the host's genome. |

| N | Antitermination for Transcription of Late Early Genes | PL | Antiterminator, RNA-binding protein and RNA polymerase cofactor, binds RNA (at Nut sites) and transfers onto the nascent RNApol that just transcribed the nut site. This RNApol modification prevents its recognition of termination sites, so normal RNA polymerase termination signals are ignored and RNA synthesis continues into distal phage genes (cII, cIII, xis, int, O, P, Q) |

| Q | Antitermination for Transcription of Late Lytic Genes | PR | Antiterminator, DNA binding protein and RNApol cofactor, binds DNA (at Qut sites) and transfers onto the initiating RNApol. This RNApol modification alters its recognition of termination sequences, so normal ones are ignored; special Q termination sequences some 20,000 bp away are effective. Q-extended transcripts include phage structural proteins (A-F, Z-J) and lysis genes (S, R, Rz and Rz1). Downregulated by Pantiq antisense mRNA during lysogeny. |

| RecA | SOS Response | Host protein | DNA repair protein, functions as a co-protease during SOS response, auto-cleaving LexA and cI and facilitating lysis. |

Lytic vs. lysogenic

An important distinction here is that between the two decisions; lysogeny and lysis on infection, and continuing lysogeny or lysis from a prophage. The latter is determined solely by the activation of RecA in the SOS response of the cell, as detailed in the section on induction. The former will also be affected by this; a cell undergoing an SOS response will always be lysed, as no cI protein will be allowed to build up. However, the initial lytic/lysogenic decision on infection is also dependent on the cII and cIII proteins.

In cells with sufficient nutrients, protease activity is high, which breaks down cII. This leads to the lytic lifestyle. In cells with limited nutrients, protease activity is low, making cII stable. This leads to the lysogenic lifestyle. cIII appears to stabilize cII, both directly and by acting as a competitive inhibitor to the relevant proteases. This means that a cell "in trouble", i.e. lacking in nutrients and in a more dormant state, is more likely to lysogenise. This would be selected for because the phage can now lie dormant in the bacterium until it falls on better times, and so the phage can create more copies of itself with the additional resources available and with the more likely proximity of further infectable cells.

A full biophysical model for lambda's lysis-lysogeny decision remains to be developed. Computer modeling and simulation suggest that random processes during infection drive the selection of lysis or lysogeny within individual cells.[26] However, recent experiments suggest that physical differences among cells, that exist prior to infection, predetermine whether a cell will lyse or become a lysogen.[27]

As a genetic tool

Lambda phage has been used heavily as a model organism and has been an excellent tool first in microbial genetics, and then later in molecular genetics.[28] Some of its uses include its application as a vector for the cloning of recombinant DNA; the use of its site-specific recombinase (int) for the shuffling of cloned DNAs by the gateway method;[29] and the application of its Red operon, including the proteins Red alpha (also called 'exo'), beta and gamma in the DNA engineering method called recombineering. The 48 kb DNA fragment of lambda phage is not essential for productive infection and can be replaced by foreign DNA,[30] which can then be replicated by the phage. Lambda phage will enter bacteria more easily than plasmids, making it a useful vector that can either destroy or become part of the host's DNA.[31] Lambda phage can also be manipulated and used as an anti-cancer vaccine that targets human aspartyl (asparaginyl) β-hydroxylase (ASPH, HAAH), which has been shown to be beneficial in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice.[32] Lambda phage has also been of major importance in the study of specialized transduction.[33]

See also

- Esther Lederberg

- Lambda holin family

- Molecular weight size marker

- Sankar Adhya

- Zygotic induction

- Corynebacteriophages – Corynephages β (beta) and ω (omega) are (proposed) members of genus Lambdavirus

References

- ^ Victor Padilla-Sanchez (2024-11-25), Bacteriophage Lambda Structure at Atomic Resolution, doi:10.5281/zenodo.14219202, retrieved 2024-11-25

- ^ Lederberg E (January 1950). "Lysogenicity in Escherichia coli strain K-12". Microbial Genetics Bulletin. 1: 5–8.; followed by Lederberg EM, Lederberg J (January 1953). "Genetic Studies of Lysogenicity in Escherichia Coli". Genetics. 38 (1): 51–64. doi:10.1093/genetics/38.1.51. PMC 1209586. PMID 17247421.

- ^ Griffiths A, Miller J, Suzuki D, Lewontin R, Gelbart W (2000). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (7th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3520-5. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Wang C, Zeng J, Wang J (April 2022). "Structural basis of bacteriophage lambda capsid maturation". Structure. 30 (4): 637–645.e3. doi:10.1016/j.str.2021.12.009. PMID 35026161. S2CID 245933331.

- ^ a b c d Rajagopala SV, Casjens S, Uetz P (September 2011). "The protein interaction map of bacteriophage lambda". BMC Microbiology. 11: 213. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-11-213. PMC 3224144. PMID 21943085.

- ^ a b c d e Casjens SR, Hendrix RW (May 2015). "Bacteriophage lambda: Early pioneer and still relevant". Virology. 479–480: 310–330. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.010. PMC 4424060. PMID 25742714.

- ^ "Escherichia phage Lambda, complete genome". 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b Campbell AM (1996). "Bacteriophages". In Neidhardt FC, Curtiss R (eds.). Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Washington, DC: ASM Press. OCLC 1156862867.

- ^ Werts C, Michel V, Hofnung M, Charbit A (February 1994). "Adsorption of bacteriophage lambda on the LamB protein of Escherichia coli K-12: point mutations in gene J of lambda responsible for extended host range". Journal of Bacteriology. 176 (4): 941–947. doi:10.1128/jb.176.4.941-947.1994. PMC 205142. PMID 8106335.

- ^ Erni B, Zanolari B, Kocher HP (April 1987). "The mannose permease of Escherichia coli consists of three different proteins. Amino acid sequence and function in sugar transport, sugar phosphorylation, and penetration of phage lambda DNA". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (11): 5238–5247. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61180-9. PMID 2951378.

- ^ Liu X, Zeng J, Huang K, Wang J (August 2019). "Structure of the mannose transporter of the bacterial phosphotransferase system". Cell Research. 29 (8): 680–682. doi:10.1038/s41422-019-0194-z. PMC 6796895. PMID 31209249.

- ^ Kobiler O, Rokney A, Oppenheim AB (April 2007). "Phage lambda CIII: a protease inhibitor regulating the lysis-lysogeny decision". PLOS ONE. 2 (4): e363. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..363K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000363. PMC 1838920. PMID 17426811.

- ^ Henkin, Tina M.; Peters, Joseph E. (2020). "Bacteriophages and Transduction". Snyder and Champness molecular genetics of bacteria (Fifth ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 293–294. ISBN 9781555819750.

- ^ a b Santangelo TJ, Artsimovitch I (May 2011). "Termination and antitermination: RNA polymerase runs a stop sign". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 9 (5): 319–329. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2560. PMC 3125153. PMID 21478900.

- ^ Thomason LC, Schiltz CJ, Court C, Hosford CJ, Adams MC, Chappie JS, Court DL (October 2021). "Bacteriophage λ RexA and RexB functions assist the transition from lysogeny to lytic growth". Molecular Microbiology. 116 (4): 1044–1063. doi:10.1111/mmi.14792. PMC 8541928. PMID 34379857.

- ^ Deighan P, Hochschild A (February 2007). "The bacteriophage lambdaQ anti-terminator protein regulates late gene expression as a stable component of the transcription elongation complex". Molecular Microbiology. 63 (3): 911–920. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05563.x. PMID 17302807.

- ^ Brammar WJ, Hadfield C (November 1984). "A programme for the construction of a lambda phage". Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 83 (Suppl): 75–88. PMID 6241940.

- ^ Guzmán P, Guarneros G (March 1989). "Phage genetic sites involved in lambda growth inhibition by the Escherichia coli rap mutant". Genetics. 121 (3): 401–409. doi:10.1093/genetics/121.3.401. PMC 1203628. PMID 2523838.

- ^ Groth AC, Calos MP (January 2004). "Phage integrases: biology and applications". Journal of Molecular Biology. 335 (3): 667–678. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.082. PMID 14687564.

- ^ Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–285. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ^ Huskey RJ (April 1969). "Multiplicity reactivation as a test for recombination function". Science. 164 (3877): 319–320. Bibcode:1969Sci...164..319H. doi:10.1126/science.164.3877.319. PMID 4887562. S2CID 27435591.

- ^ Blanco M, Devoret R (March 1973). "Repair mechanisms involved in prophage reactivation and UV reactivation of UV-irradiated phage lambda". Mutation Research. 17 (3): 293–305. doi:10.1016/0027-5107(73)90001-8. PMID 4688367.

- ^ "Barbara J. Meyer". HHMI Interactive.

- ^ Burz DS, Beckett D, Benson N, Ackers GK (July 1994). "Self-assembly of bacteriophage lambda cI repressor: effects of single-site mutations on the monomer-dimer equilibrium". Biochemistry. 33 (28): 8399–8405. doi:10.1021/bi00194a003. PMID 8031775.

- ^ Ptashne M (2004). A genetic switch: phage lambda revisited (3rd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-87969-716-7.

- ^ Arkin A, Ross J, McAdams HH (August 1998). "Stochastic kinetic analysis of developmental pathway bifurcation in phage lambda-infected Escherichia coli cells". Genetics. 149 (4): 1633–1648. doi:10.1093/genetics/149.4.1633. PMC 1460268. PMID 9691025.

- ^ St-Pierre F, Endy D (December 2008). "Determination of cell fate selection during phage lambda infection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (52): 20705–20710. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10520705S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808831105. PMC 2605630. PMID 19098103.

- ^ Pitre, Emmanuelle; te Velthuis, Aartjan J. W. (2021-01-01), Cameron, Craig E.; Arnold, Jamie J.; Kaguni, Laurie S. (eds.), "Chapter Four - Understanding viral replication and transcription using single-molecule techniques", The Enzymes, Viral Replication Enzymes and their Inhibitors Part A, 49, Academic Press: 83–113, doi:10.1016/bs.enz.2021.07.005, PMID 34696840, S2CID 239573473, retrieved 2023-11-28

- ^ Reece-Hoyes, John S.; Walhout, Albertha J. M. (2018-01-01). "Gateway Recombinational Cloning". Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2018 (1): pdb.top094912. doi:10.1101/pdb.top094912. ISSN 1940-3402. PMC 5935001. PMID 29295908.

- ^ Feiss, Michael; Catalano, Carlos Enrique (2013), "Bacteriophage Lambda Terminase and the Mechanism of Viral DNA Packaging", Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet], Landes Bioscience, retrieved 2023-11-28

- ^ Smith, George P. (1985). "Filamentous Fusion Phage: Novel Expression Vectors that Display Cloned Antigens on the Virion Surface". Science. 228 (4705): 1315–1317. Bibcode:1985Sci...228.1315S. doi:10.1126/science.4001944. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1694587. PMID 4001944.

- ^ Iwagami, Yoshifumi; Casulli, Sarah; Nagaoka, Katsuya; Kim, Miran; Carlson, Rolf I.; Ogawa, Kosuke; Lebowitz, Michael S.; Fuller, Steve; Biswas, Biswajit; Stewart, Solomon; Dong, Xiaoqun; Ghanbari, Hossein; Wands, Jack R. (2017). "Lambda phage-based vaccine induces antitumor immunity in hepatocellular carcinoma". Heliyon. 3 (9): e00407. Bibcode:2017Heliy...300407I. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00407. PMC 5619992. PMID 28971150.

- ^ "7.14E: Bacteriophage Lambda as a Cloning Vector". Biology LibreTexts. 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

Further reading

- Watson J, Baker T, Bell S, Gann A, Levine M, Losick R. Molecular Biology of the Gene (International Edition) (6th ed.).

- Ptashne M, Hopkins N (August 1968). "The operators controlled by the lambda phage repressor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 60 (4): 1282–7. Bibcode:1968PNAS...60.1282P. doi:10.1073/pnas.60.4.1282. PMC 224915. PMID 5244737.

- Meyer BJ, Kleid DG, Ptashne M (December 1975). "Lambda repressor turns off transcription of its own gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (12): 4785–89. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.4785M. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.12.4785. PMC 388816. PMID 1061069.

- Brüssow H, Hendrix RW (January 2002). "Phage genomics: small is beautiful". Cell. 108 (1): 13–16. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00637-7. PMID 11792317.

- Dodd IB, Shearwin KE, Egan JB (April 2005). "Revisited gene regulation in bacteriophage lambda". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 15 (2): 145–152. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2005.02.001. PMID 15797197.

- Friedman DI, Court DL (April 2001). "Bacteriophage lambda: alive and well and still doing its thing". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 4 (2): 201–207. doi:10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00189-2. PMID 11282477.

- Gottesman ME, Weisberg RA (December 2004). "Little lambda, who made thee?". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 68 (4): 796–813. doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.4.796-813.2004. PMC 539004. PMID 15590784.

- Hendrix RW, Smith MC, Burns RN, Ford ME, Hatfull GF (March 1999). "Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (5): 2192–2197. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.2192H. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.5.2192. PMC 26759. PMID 10051617.

- Kitano H (March 2002). "Systems biology: a brief overview". Science. 295 (5560): 1662–1664. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1662K. doi:10.1126/science.1069492. PMID 11872829. S2CID 2703843.

- Ptashne, M. "A Genetic Switch: Phage Lambda Revisited", 3rd edition 2003

- Ptashne M (June 2005). "Regulation of transcription: from lambda to eukaryotes". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 30 (6): 275–279. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.003. PMID 15950866.

- Snyder L, Champness W (2007). Molecular Genetics of Bacteria (3rd ed.). (Contains an informative and well illustrated overview of bacteriophage lambda)

- "Bacteriophage Lambda Infection". Splasho. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. (illustrates genes active at all stages in lifecycle)

External links

- Life Cycle, Basic Animation of Lambda Lifecyecle (illustrates infection and lytic/lysogenic pathways with some protein and transcription detail)

- Time-lapse microscopy video from MIT showing both lysis and lysogeny by phage lambda

- Lambda Phage Life cycle (basic visual demonstration of Lambda bacteriophage life cycle)

- Lambda Phage genome in GenBank

- Lambda Phage Reference Proteome from UniProt

- Lambda Phage Protein Structures in NCBI (3D display of protein structures for bacteriophage Lambda)

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !