Berlin German

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (August 2017) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Berlin German | |

|---|---|

| Berlinese | |

| Berliner Dialekt, Berliner Mundart, Berlinerisch, Berlinisch | |

| Region | Berlin |

Early form | |

| German alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | berl1235 |

| IETF | de-u-sd-debe |

Berlin German, or Berlinese (High German: Berliner Dialekt, Berliner Mundart, Berlinerisch or Berlinisch; derogative: Berliner Schnauze, pronounced [bɛʁˌliːnɐ ˈʃnaʊtsə] ), is the regiolect spoken in the city of Berlin as well as its surrounding metropolitan area. It originates from a Brandenburgisch dialect. However, several phrases in Berlin German are typical of and unique to the city, indicating the manifold origins of immigrants, such as the Huguenots from France.

Overview

The area of Berlin was one of the first to abandon East Low German as a written language, which occurred in the 16th century, and later also as a spoken language. That was the first regiolect of Standard German with definite High German roots but a Low German substratum apparently formed (Berlinerisch may therefore be considered an early form of Missingsch). Only recently has the new dialect expanded into the surroundings, which had used East Low German.

Since the 20th century, the Berlin dialect has been a colloquial standard in the surrounding Brandenburg region. However, in Berlin proper, especially in the former West Berlin, the dialect is now seen more as a sociolect, largely through increased immigration and trends among the educated population to speak Standard German in everyday life.[1]

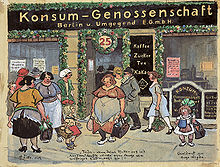

Occasionally, the regiolect is found on advertising.

History

The area now known as Berlin was originally settled by Germanic tribes, who may have given their name to the Havel River in West Berlin. The area was later inhabited by immigrant Slavs, as evidenced by place and field names such as Kladow, Buckow and Köpenick, and by the Berlin word Kietz, ‘city neighborhood.’

The city of Berlin lies south of the Benrath Line and has been influenced by Low and Central German since its first documented mention in 1237. From 1300-1500, immigration from the Flemish areas of the Holy Roman Empire the East Low German spoken in Berlin underwent a number of changes but was eventually abandoned as a colloquial language. This resulted in a separate variety of Standard High German with a clear Middle German basis but a strong Low German substrate. Only recently has this new dialect spread to the surrounding area, which had previously remained East Low German. Berlin German has parallels to Colognian ("Kölsch"), which also has strong features of a regiolect and has been shaped by immigration over the centuries. Both exhibit the characteristic softening of initial sounds, such as in jut (gut, 'good') and jehen (gehen, 'to go').

In the late 18th century, the common colloquial Brandenburg (or Markish) dialect, was replaced by a Central German koiné based on Upper Saxon. This is similar to developments in other Low German regions, which first developed Missingsch dialects as a mixed language with the law firm language and changed their use to colloquial language. The newly created koiné dialect, which was very similar to modern Berlin German, adopted individual words (ick, det, wat, doof) from the neighboring Low German-speaking areas.

Berlin was a destination for ever increasing immigration starting in 1871. Large numbers of immigrants from Saxony and Siliesia pushed back against some of the Low German elements of the Berlin dialect. The 1900s saw large waves of emigration out of Berlin and into West Germany, the first starting in1945 and the second in 1961.

Dialect

Due to the extensive commonalities with High German, Berlin German is classified as a dialect of German. Berlinish has long been looked down upon as a dialect of "the common people," and the educated class has historically distanced themselves through use of the High German dialect, which is considered the standard.

Berliners use written conventions of High German, but there does exist a Brandenburg-Berlin dictionary which includes vocabulary specific to the Berlin dialect. When recording Berlinish speech in writing, there is no consensus on transcription. Pronunciation varies among speakers and individual speakers may alter their pronunciation depending on communicative context. For published texts, each publisher determines its own transcription system for embedded passages of Berlin German within texts. The majority use High German orthography, only changing letters or words to mark prominent differences in pronunciation.

Present Day

Berlin German is the central language variety of a regiolect area extending across Berlin, Brandenburg, and parts of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Saxony-Anhalt. In Brandenburg, Berlin German has been considered the colloquial variety since the 20th century, but In Berlin itself, especially in West Berlin, an influx of people with educated middle-class dialects has resulted in Berlin German becoming one of many dialects in the region, no longer a regiolect but a sociolect.

Phonology

Berliner pronunciation is similar to that of other High German varieties. Nevertheless, it maintains unique characteristics, which set it apart from other variants. The most notable are the strong contraction trends over several words and the rather irreverent adaptation of foreign words and anglicisms that are difficult to understand for many speakers of Upper German. Also, some words contain the letter j (representing IPA: [j]) instead of g, as is exemplified in the word for good, in which gut becomes jut.

'j' in place of 'g'

Word initially and after front vowels and approximants, 'g' is realized as the voiced palatal approximant [j]. After back vowels, the sound is pronounced as a voiced velar fricative [ɣ], the same sound as High German 'r.'

Monophthongs

Many diphthongs are realized as long monophthongs in Berlin German: au [au] to oo [o:], ei [aɪ] to ee [e:]. However, this pattern holds only for words with a historic au/oo or ei/ee split between the Middle High German and Low German dialects. For example, ein/een ("a/an") and Rauch/Rooch ("smoke") conform to the split, but Eis ("ice") and Haus ("house") do not.

High German Consonant Shift

As a Central German dialect bordering Low German regions, Berlin German does not exhibit all features of the High German consonant shift, retaining some older features, such as geminate 'p' [pp], as in Appel and Kopp for High German Apfel and Kopf, as well as det/dit, wat, and et for das, was, and es, respectively.

Reductions and Contractions

Berlin dialect speakers often reduce and contract words that are separated in High German. For example, High German auf dem becomes Berlin German uffm.

Grammar

Berlinese grammar contains some notable differences from that of Standard German. For instance, the accusative case and dative case are not distinguished. Similarly, conjunctions that are distinguished in standard German are not in Berlinese. For example, in Standard German, wenn (when, if) is used for conditional, theoretical or consistent events, and wann (when) is used for events that are currently occurring or for questions. There is no difference between the two in Berlinese.[2]

Genitive forms are also replaced by prepositional accusative forms, some still with an inserted pronoun: dem sein Haus (this one his house) rather than the standard sein Haus (his house). Plural forms often have an additional -s, regardless of the standard plural ending.[3]

Words ending in -ken are often written colloquially and pronounced as -sken.

Pronouns

Personal Pronouns

The accusative and dative case pronouns are almost identical in Berlin German. While in High German the first-person singular accusative is mich, and the first-person singular dative is mir, Berlin German uses mir for both cases. A popular saying is "Der Berlina sacht imma mir, ooch wenn et richtich is"[4][5] ("The Berliner always says mir, even if it is right."). In contrast, speakers in southern Brandenburg, use the pronoun mich in both cases, as in "Bringt mich mal die Zeitung" ("Bring me the newspaper.").

The lack of distinction between these pronouns may be attributed to the influence of Brandenburg Low German, in which both mir and mich sound like mi [mi] or mai [maɪ]. Second-person singular familiar pronouns dir (dative) and dich (accusative) follow the same pattern, sounding like di [di] or dai [daɪ].

Berlin German uses ick or icke for first-person singular subject pronoun ich, as shown in the old Berlin saying, Icke, dette, kieke mal, Oogn, Fleesch und Beene, wenn de mir nich lieben tust, lieb ick mir alleene. The high German equivalent is Ich, das, schau mal, Augen, Fleisch und Beine, wenn du mich nicht liebst, liebe ich mich alleine. ("I, that, just look, eyes, flesh, and legs, if you don't love me, I love me alone.")

Personal pronouns:

| 1st sg. | 2nd sg. | 3rd sg.: m. / f. / n. |

1st pl. | 2nd pl. | 3rd pl. | polite address | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | ick icke (absolute, standing without verb) -'k (enclitic) |

du due (alternatively when absolute, rare) -e (enclitic) |

er | sie, se | et -'t (enclitic) |

wir | ihr | sie, se | Sie, Se |

| Dat.-Acc. | mir (emphatic: mia, unemphatic: ma) | dir | ihn ihm (occasionally, and then more common in Acc.) |

ihr | et -'t (enclitic) |

uns | euch | sie, se ihr (occasionally) |

Ihn' Sie (alternatively after prepositions) |

Interrogative pronoun:

| m. (f.) | n. | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom. | wer | wat |

| Gen. | wems wemst | |

| Dat.-Acc. | wem |

Er/Wir for Direct Address

Er ('he') as a form of direct address was previously widespread among German speakers when speaking to subordinates and those of lower social rank.[8] In modern Berlin German, er may be used for direct address, as in Hatter denn ooch’n jült’jen Fahrausweis? ("Hat er denn auch einen gültigen Fahrausweis?"or "Does he [=do you] also have a valid ticket?" ). This can also be see with the feminine sie (she), as in Hattse denn die fümf[9] Euro nich’n bisken kleena? ("Hat sie denn die fünf Euro nicht ein bisschen kleiner? or “Doesn't she [=don't you] have something smaller than five Euros?") .

The third-person plural nominative wir is also sometimes used for second-person address in Berlin German. "Na, hamwa nu det richt’je Bier jewählt? ("Na, haben wir nun das richtige Bier gewählt?" or "Well, have we now selected the right beer?")

Idioms

The Berlin regiolect has a number of distinctive idioms, including the following:[10]

- JWD (janz weit draußen) = Really far out there

- Na Mann, du hast heut’ aba wieda ’ne Kodderschnauze (Literally: "Well, man, you have a bit of a dirty snout today.") This expression means the addressee has a loose tongue, giving their unsolicited comments.

- bis in die Puppen (Literally: "until in the dolls") This expression, meaning "until the wee hours" originated in the 18th century. The Berlin park Großer Tiergarten had a square decorated with statues called “The Dolls.” If you strolled particularly far on Sundays, you walked “until you were in the dolls.”

- Da kamma nich meckan. "You can't complain about that." This is supposedly the highest praise a Berliner can offer.

See also

References

- ^ Berlinerisch, Deutsche Welle

- ^ Icke, icke bin Berlina, wer mir haut, den hau ich wieda Wölke Archived December 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Viertel-Dreiviertel-Verbreitungskarte

- ^ Hans Ostwald: Der Urberliner. Paul Franke, Berlin 1928

- ^ Cf: Icke, icke bin Berlina, wer mir haut, den hau ick wieda nach Wölke (Memento vom 5. Dezember 2010 im Internet Archive)

- ^ Hans Meyer: Der richtige Berliner in Wörtern und Redensarten

- [Hans Meyer]: Der richtige Berliner in Wörtern und Redensarten. 2nd edition, Druck und Verlag von H. S. Hermann, Berlin, 1879, especially p. VIII, X, 23f. s.v. Ick, Icke, and 70 s.v. Wemst

- Hans Meyer: Der Richtige Berliner in Wörtern und Redensarten. 6th edition, Druck und Verlag von H. S. Hermann, Berlin, 1904, p. XV

- Hans Meyer, Siegfried Mauermann, Walther Kiaulehn: Der richtige Berliner in Wörtern und Redensarten verfaßt von Hans Meyer und Siegfried Mauermann bearbeitet und ergänzt von Walther Kiaulehn. 13th edition, Verlag C. H. Beck, 2000, p. 49f.

- ^ Karl Lentzner: Der Berlinische Dialekt. Untersucht und nach Aufzeichnungen „richtiger Berliner“ herausgegeben. 1893, p. 10

- ^ Georg Büchners Dramenfragment Woyzeck: „Ich hab’s gesehn, Woyzeck; er hat an die Wand gepißt, wie ein Hund“

- ^ Hans Meyer: Der Richtige Berliner in Wörtern und Redensarten. 6. Auflage. Berlin 1904, S. 2 (Stichwort Abklawieren) u. vgl. S. XIII Digitalisat. (Memento vom 8. August 2014 im Internet Archive; PDF; 6,5 MB)

- ^ Berliner Mundart und weitere Sprüche. berlin.de

External links

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !