Bracero Program

This article is written like a research paper or scientific journal. (January 2022) |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Chicanos and Mexican Americans |

|---|

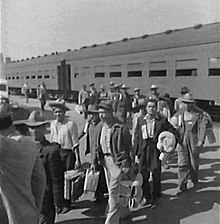

The Bracero Program (from the Spanish term bracero [bɾaˈse.ɾo], meaning "manual laborer" or "one who works using his arms") was a U.S. Government-sponsored program that imported Mexican farm and railroad workers into the United States between the years 1942 and 1964.

The program, which was designed to fill agriculture shortages during World War II, offered employment contracts to 5 million braceros in 24 U.S. states. It was the largest guest worker program in U.S. history.[1]

The program was the result of a series of laws and diplomatic agreements, initiated on August 4, 1942, when the United States signed the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement with Mexico.[2] For these farmworkers, the agreement guaranteed decent living conditions (sanitation, adequate shelter, and food) and a minimum wage of 30 cents an hour, as well as protections from forced military service, and guaranteed that a part of wages was to be put into a private savings account in Mexico. The program also allowed the importation of contract laborers from Guam as a temporary measure during the early phases of World War II.[3]

The agreement was extended with the Migrant Labor Agreement of 1951 (Pub. L. 82–78), enacted as an amendment to the Agricultural Act of 1949 by the United States Congress,[4] which set the official parameters for the Bracero Program until its termination in 1964.[1]

In studies published in 2018 and 2023, it was found that the Bracero Program did not have an adverse effect on the wages or employment for American-born farm workers, [5] and that termination of the program had adverse impact on American-born farmers and resulted in increased farm mechanization.[6]

Since abolition of the Bracero Program, temporary agricultural workers have been admitted with H-2 and H-2A visas.

Introduction

The Bracero Program operated as a joint program under the State Department, the Department of Labor, and the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) in the Department of Justice. Under this pact, the laborers were promised decent living conditions in labor camps, such as adequate shelter, food and sanitation, as well as a minimum wage pay of 30 cents an hour. The agreement also stated that braceros would not be subject to discrimination such as exclusion from "white" areas.[7]

This program, which commenced in Stockton, California in August 1942,[8] was intended to fill the labor shortage in agriculture because of World War II. In Texas, the program was banned by Mexico for several years during the mid-1940s due to the discrimination and maltreatment of Mexicans, which included lynchings along the border. Texas Governor Coke Stevenson pleaded on several occasions to the Mexican government that the ban be lifted to no avail.[9] The program lasted 22 years and offered employment contracts to 5 million braceros in 24 U.S. states—becoming the largest foreign worker program in U.S. history.[1]

From 1942 to 1947, only a relatively small number of braceros were admitted, accounting for less than 10 percent of U.S. hired workers.[10] Yet both U.S. and Mexican employers became heavily dependent on braceros for willing workers; bribery was a common way to get a contract during this time. Consequently, several years of the short-term agreement led to an increase in undocumented immigration and a growing preference for operating outside of the parameters set by the program.[7]

Moreover, Truman's Commission on Migratory Labor in 1951 disclosed that the presence of Mexican workers depressed the income of American farmers, even as the U.S. Department of State urged a new bracero program to counter the popularity of communism in Mexico. Furthermore, it was seen as a way for Mexico to be involved in the Allied armed forces. The first braceros were admitted on September 27, 1942, for the sugar-beet harvest season. From 1948 to 1964, the U.S. allowed in on average 200,000 braceros per year.[7]

Railroad workers

Bracero railroad workers were often distinguished from their agricultural counterparts. Railroad workers closely resembled agriculture contract workers between Mexico and the U.S. Being a bracero on the railroad meant lots of demanding manual labor, including tasks such as expanding rail yards, laying track at port facilities, and replacing worn rails. Railroad work contracts helped the war effort by replacing conscripted farmworkers, staying in effect until 1945 and employing about 100,000 men."[11]

Southern Pacific Railroad

In 1942 when the Bracero Program came to be, it was not only agriculture work that was contracted, but also railroad work. Just like braceros working in the fields, Mexican contract workers were recruited to work on the railroads. The Southern Pacific railroad was having a hard time keeping full-time rail crews on hand. The dilemma of short handed crews prompted the railway company to ask the government permission to have workers come in from Mexico. The railroad version of the Bracero Program carried many similarities to agricultural braceros. It was written that, "The bracero railroad contract would preserve all the guarantees and provisions extended to agricultural workers."[12] Only eight short months after agricultural braceros were once again welcomed to work, so were braceros on the railroads. The "Immigration and Naturalization authorized, and the U.S. attorney general approved under the 9th Proviso to Section 3 of the Immigration Act of February 5, 1917, the temporary admission of unskilled Mexican non-agricultural workers for railroad track and maintenance-of-way employment. The authorization stipulated that railroad braceros could only enter the United States for the duration of the war."[12] Over the course of the next few months, braceros began coming in by the thousands to work on railroads. Multiple railroad companies began requesting Mexican workers to fill labor shortages. Bracero railroaders were also in understanding of an agreement between the U.S. and Mexico to pay a living wage, and provide adequate food, housing, and transportation. Working in the U.S. was not easy for bracero railroaders. Oftentimes, just like agricultural braceros, the railroaders were subject to rigged wages, harsh or inadequate living spaces, food scarcity, and racial discrimination [citation needed]. Exploitation of the braceros went on well into the 1960s.

1951 negotiations to termination

American growers longed for a system that would admit Mexican workers and guarantee them an opportunity to grow and harvest their crops, and place them on the American market. Thus, during negotiations in 1948 over a new bracero program, Mexico sought to have the United States impose sanctions on American employers of undocumented workers.[citation needed]

President Truman signed Public Law 78 (which did not include employer sanctions) in July 1951.[13][14] Soon after it was signed, United States negotiators met with Mexican officials to prepare a new bilateral agreement. This agreement made it so that the U.S. government were the guarantors of the contract, not U.S. employers. The braceros could not be used as replacement workers for U.S. workers on strike; however, the braceros were not allowed to go on strike or renegotiate wages. The agreement set forth that all negotiations would be between the two governments.[1]

A year later, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 was passed by the 82nd United States Congress whereas President Truman vetoed the U.S. House immigration and nationality legislation on June 25, 1952.[15] The H.R. 5678 bill conceded a federal felony for knowingly concealing, harboring, or shielding a foreign national or illegal immigrant.[16] However the Texas Proviso stated that employing unauthorized workers would not constitute as "harboring or concealing" them. This also led to the establishment of the H-2A visa program,[17] which enabled laborers to enter the U.S. for temporary work. There were a number of hearings about the United States–Mexico migration, which overheard complaints about Public Law 78 and how it did not adequately provide them with a reliable supply of workers. Simultaneously, unions complained that the braceros' presence was harmful to U.S. workers.[10]

The outcome of this meeting was that the United States ultimately got to decide how the workers would enter the country by way of reception centers set up in various Mexican states and at the United States border. At these reception centers, potential braceros had to pass a series of examinations. The first step in this process required that the workers pass a local level selection before moving onto a regional migratory station where the laborers had to pass a number of physical examinations.

Lastly, at the U.S. reception centers, workers were inspected by health departments, stripped & sprayed with DDT a dangerous pesticide.[10][18]

They were then sent to contractors that were looking for workers.[10] Operations were primarily run by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) along with other military personnel. Braceros frequently dealt with harassment from these officials and could be kept for extended periods of time in the examination rooms.[19] These rooms held as many as 40 men at a time, and migrants would have to wait 6 or more hours to be examined.[19] According to first hand accounts, personnel would often process 800 to 1600 braceros at a time and, on occasion, upwards of 3100.[19] The invasive health procedures and overcrowded processing centers would continue to persist throughout the program's 22-year tenure.[19]

To address the overwhelming amount of undocumented migrants in the United States, the Immigration and Naturalization Service launched Operation Wetback in June 1954, as a way to repatriate illegal laborers back to Mexico. The illegal workers who came over to the states at the initial start of the program were not the only ones affected by this operation, there were also massive groups of workers who felt the need to extend their stay in the U.S. well after their labor contracts were terminated.[10]

In the first year, over a million Mexicans were sent back to Mexico; 3.8 million were repatriated when the operation was finished. The criticisms of unions and churches made their way to the U.S. Department of Labor, as they lamented that the braceros were negatively affecting the U.S. farmworkers in the 1950s. In 1955, the AFL and CIO spokesman testified before a Congressional committee against the program, citing lack of enforcement of pay standards by the Labor Department.[20] The Department of Labor eventually acted upon these criticisms and began closing numerous bracero camps in 1957–1958, they also imposed new minimum wage standards and in 1959 they demanded that American workers recruited through the Employment Service be entitled to the same wages and benefits as the braceros.[21]

The Department of Labor continued to try to get more pro-worker regulations passed, however the only one that was written into law was the one guaranteeing U.S. workers the same benefits as the braceros, which was signed in 1961 by President Kennedy as an extension of Public Law 78. After signing, Kennedy said, "I am aware ... of the serious impact in Mexico if many thousands of workers employed in this country were summarily deprived of this much-needed employment." Thereupon, bracero employment plummeted; going from 437,000 workers in 1959 to 186,000 in 1963.[10]

During a 1963 debate over extension, the House of Representatives rejected an extension of the program. However, the Senate approved an extension that required U.S. workers to receive the same non-wage benefits as braceros. The House responded with a final one-year extension of the program without the non-wage benefits, and the Bracero Program saw its demise in 1964.[10]

Emergency Farm Labor Program and federal public laws

1942-1947 Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program

| Year | Number of Braceros | Applicable U.S. Law | Date of Enactment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | 4,203 | 56 Stat. 1759, E.A.S. 278 - No. 312 [22] | August 4, 1942 |

| 1943 | (44,600)[23] | Pub. L. 78–45 | 57 Stat. 70 | April 29, 1943 |

| 1944 | 62,170 | Pub. L. 78–229 | 58 Stat. 11 | February 14, 1944 |

| 1945 | (44,600) | Pub. L. 79–269 | 59 Stat. 632 | December 28, 1945 |

| 1946 | (44,600) | Pub. L. 79–731 | 60 Stat. 1062 | August 14, 1946 |

| 1947 | (30,000)[24] | Pub. L. 80–40 | 61 Stat. 55 | April 28, 1947 |

| 1947 | (30,000)[24] | Pub. L. 80–76 | 61 Stat. 106 | May 26, 1947 |

| 1947 | (30,000)[24] | Pub. L. 80–131 | 61 Stat. 202 | June 30, 1947 |

| 1947 | (30,000)[24] | Pub. L. 80–298 | 61 Stat. 694 | July 31, 1947 |

1948-1964 Farm Labor Supply Program

| Year | Number of Braceros | Applicable U.S. Law | Date of Enactment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | (30,000) | Pub. L. 80–893 | 62 Stat. 1238 | July 3, 1948 |

| 1948–50 | (79,000/yr)[25] | Period of administrative agreements | |

| 1951 | 192,000[26] | Pub. L. 82–78 | 65 Stat. 119 | July 12, 1951 |

| 1952 | 197,100 | Agricultural Act, 1949 Amended - Title V | July 12, 1951 |

| 1953 | 201,380 | Pub. L. 83–237 | 67 Stat. 500 | August 8, 1953 |

| 1954 | 309,033 | Pub. L. 83–309 | 68 Stat. 28 | March 16, 1954 |

| 1955 | 398,650 | Pub. L. 84–319 | 69 Stat. 615 | August 9, 1955 |

| 1956 | 445,197 | Agricultural Act, 1949 Amended - Title V | July 12, 1951 |

| 1957 | 436,049 | Agricultural Act, 1949 Amended - Title V | July 12, 1951 |

| 1958 | 432,491 | Pub. L. 85–779 | 72 Stat. 934 | August 27, 1958 |

| 1959 | 437,000 | Agricultural Act, 1949 Amended - Title V | July 12, 1951 |

| 1960 | 319,412 | Pub. L. 86–783 | 74 Stat. 1021 | September 14, 1960 |

| 1961 | 296,464 | Pub. L. 87–345 | 75 Stat. 761 | October 3, 1961 |

| 1962 | 198,322 | Agricultural Act, 1949 Amended - Title V | July 12, 1951 |

| 1963 | 186,000 | Agricultural Act, 1949 Amended - Title V | July 12, 1951 |

| 1964 | 179,298 | Pub. L. 88–203 | 77 Stat. 363 | December 13, 1963 |

The workers who participated in the bracero program have generated significant local and international struggles challenging the U.S. government and Mexican government to identify and return 10 percent mandatory deductions taken from their pay, from 1942 to 1948, for savings accounts that they were legally guaranteed to receive upon their return to Mexico at the conclusion of their contracts. Many field working braceros never received their savings, but most railroad working braceros did.[27]

Lawsuits presented in federal courts in California, in the late 1990s and early 2000s (decade), highlighted the substandard conditions and documented the ultimate destiny of the savings accounts deductions, but the suit was thrown out because the Mexican banks in question never operated in the United States. Today, it is stipulated that ex-braceros can receive up to $3,500.00 as compensation for the 10% only by supplying check stubs or contracts proving they were part of the program during 1942 to 1948. It is estimated that, with interest accumulated, $500 million is owed to ex-braceros, who continue to fight to receive the money owed to them.[27]

Organized labor

Notable strikes

- January–February (exact dates aren't noted) 1943: In Burlington, Washington, braceros strike because farmers were paying higher wages to Anglos than to the braceros doing similar work[28]

- 1943: In Medford, Oregon, one of the first notable strikes was by a group of braceros that[29] staged a work stoppage to protest their pay based on per box versus per hour. The growers agreed to pay them 75 cents an hour versus the 8 or 10 cents per box.

- May 1944: Braceros in Preston, Idaho, struck over wages[30]

- July and September 1944: Braceros near Rupert and Wilder, Idaho, strike over wages[31]

- October 1944: Braceros in Sugar City and Lincoln, Idaho refused to harvest beets after earning higher wages picking potatoes[32]

- May–June 1945: Bracero asparagus cutters in Walla Walla, Washington, struck for twelve days complaining they grossed only between $4.16 and $8.33 in that time period[33]

- June 1945: Braceros from Caldwell-Boise sugar beet farms struck when hourly wages were 20 cents less than the established rate set by the County Extension Service. They won a wage increase.[34]

- June 1945: In Twin Falls, Idaho, 285 braceros went on strike against the Amalgamated Sugar Company for two days which resulted in them effectively receiving a 50 cent raise which put them 20 cents over the prevailing wage of the contracted labor[35]

- June 1945: Three weeks later braceros at Emmett struck for higher wages[36]

- July 1945: In Idaho Falls, 170 braceros organized a sit-down strike that lasted nine days after fifty cherry pickers refused to work at the prevailing rate.[37]

- October 1945: In Klamath Falls, Oregon, braceros and transient workers from California refuse to pick potatoes due to insufficient wages[38]

- A majority of Oregon's Mexican labor camps were affected by labor unrest and stoppages in 1945[39]

- November 1946: In Wenatchee, Washington, 100 braceros refused to be transported to Idaho to harvest beets and demanded a train back to Mexico.[40]

The number of strikes in the Pacific Northwest is much longer than this list. Two strikes, in particular, should be highlighted for their character and scope: the Japanese-Mexican strike of 1943 in Dayton, Washington[41] and the June 1946 strike of 1000 plus braceros that refused to harvest lettuce and peas in Idaho.

1943 strike

The 1943 strike in Dayton, Washington, is unique in the unity it showed between Mexican braceros and Japanese-American workers. The wartime labor shortage not only led to tens of thousands of Mexican braceros being used on Northwest farms, it also saw the U.S. government allow some ten thousand Japanese Americans, who were placed against their will in internment camps during World War II, to leave the camps in order to work on farms in the Northwest.[42] The strike at Blue Mountain Cannery erupted in late July. After "a white female came forward stating that she had been assaulted and described her assailant as 'looking Mexican' ... the prosecutor's and sheriff's office imposed a mandatory 'restriction order' on both the Mexican and Japanese camps."[43] No investigation took place nor were any Japanese or Mexican workers asked their opinions on what happened.

The Walla Walla Union-Bulletin reported the restriction order read:

Males of Japanese and or Mexican extraction or parentage are restricted to that area of Main Street of Dayton, lying between Front Street and the easterly end of Main Street. The aforesaid males of Japanese and or Mexican extraction are expressly forbidden to enter at any time any portion of the residential district of said city under penalty of law.[44]

The workers' response came in the form of a strike against this perceived injustice. Some 170 Mexicans and 230 Japanese struck. After multiple meetings including some combination of government officials, Cannery officials, the county sheriff, the Mayor of Dayton and representatives of the workers, the restriction order was voided. Those in power actually showed little concern over the alleged assault. Their real concern was ensuring the workers got back into the fields. Authorities threatened to send soldiers to force them back to work.[45] Two days later the strike ended. Many of the Japanese and Mexican workers had threatened to return to their original homes, but most stayed there to help harvest the pea crop.

Reasons for discontent

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wik.ipedia.Pro. (August 2017) |

First, like braceros in other parts of the U.S., those in the Northwest came to the U.S. looking for employment with the goal of improving their lives. Yet, the power dynamic all braceros encountered offered little space or control by them over their living environment or working conditions. As Gamboa points out, farmers controlled the pay (and kept it very low), hours of work and even transportation to and from work. Transportation and living expenses from the place of origin to destination, and return, as well as expenses incurred in the fulfillment of any requirements of a migratory nature, should have been met by the employer. Most employment agreements contained language to the effect of, "Mexican workers will be furnished without cost to them with hygienic lodgings and the medical and sanitary services enjoyed without cost to them will be identical with those furnished to the other agricultural workers in regions where they may lend their services." These were the words of agreements that all bracero employers had to come to but employers often showed that they couldn't stick with what they agreed on. Braceros had no say on any committees, agencies or boards that existed ostensibly to help establish fair working conditions for them.[46] The lack of quality food angered braceros all over the U.S. According to the War Food Administrator, "Securing able cooks who were Mexicans or who had had experience in Mexican cooking was a problem that was never completely solved."[47]

John Willard Carrigan, who was an authority on this subject after visiting multiple camps in California and Colorado in 1943 and 1944, commented, "Food preparation has not been adapted to the workers' habits sufficiently to eliminate vigorous criticisms. The men seem to agree on the following points: 1.) the quantity of food is sufficient, 2.) evening meals are plentiful, 3.) breakfast often is served earlier than warranted, 4.) bag lunches are universally disliked ... In some camps, efforts have been made to vary the diet more in accord with Mexican taste. The cold sandwich lunch with a piece of fruit, however, persists almost everywhere as the principal cause of discontent."[48]

Not only was the pay extremely low, but braceros often weren't paid on a timely basis. A letter from Howard A. Preston describes payroll issues that many braceros faced, "The difficulty lay chiefly in the customary method of computing earnings on a piecework basis after a job was completed. This meant that full payment was delayed for long after the end of regular pay periods. It was also charged that time actually worked was not entered on the daily time slips and that payment was sometimes less than 30 cents per hour. April 9, 1943, the Mexican Labor Agreement is sanctioned by Congress through Public Law 45 which led to the agreement of a guaranteed a minimum wage of 30 cents per hour and "humane treatment" for workers involved in the program.[49]

Wage discrepancies

Despite what the law extended to braceros and what growers agreed upon in their contracts, braceros often faced rigged wages, withheld pay, and inconsistent disbursement of wages. Bracero railroaders were usually paid by the hour, whereas agricultural braceros sometime were paid by the piece of produce which was packaged. Either way, these two contracted working groups were shorted more times than not. Bracero contracts indicated that they were to earn nothing less than minimum wage. In an article titled, "Proof of a Life Lived: The Plight of the Braceros and What It Says About How We Treat Records" written by Jennifer Orsorio, she describes this portion of wage agreement, "Under the contract, the braceros were to be paid a minimum wage (no less than that paid to comparable American workers), with guaranteed housing, and sent to work on farms and in railroad depots throughout the country - although most braceros worked in the western United States."[50] Unfortunately, this was not always simple and one of the most complicated aspects of the bracero program was the worker's wage garnishment. The U.S. and Mexico made an agreement to garnish bracero wages, save them for the contracted worker (agriculture or railroad), and put them into bank accounts in Mexico for when the bracero returned to their home. Like many, braceros who returned home did not receive those wages. Many never had access to a bank account at all. It is estimated that the money the U.S. "transferred" was about $32 million.[50] Often braceros would have to take legal action in attempts to recover their garnished wages. According to bank records money transferred often came up missing or never went into a Mexican banking system. In addition to the money transfers being missing or inaccessible by many braceros, the everyday battles of wage payments existed up and down the railroads, as well as in all the country's farms.

In a newspaper article titled "U.S. Investigates Bracero Program", published by The New York Times on January 21, 1963, claims the U.S. Department of Labor was checking false-record keeping. In this short article the writer explains, "It was understood that five or six prominent growers have been under scrutiny by both regional and national officials of the department."[51] This article came out of Los Angeles particular to agriculture braceros. However, just like many other subjections of the bracero, this article can easily be applied to railroaders.

Reasons for strikes in the Northwest

One key difference between the Northwest and braceros in the Southwest or other parts of the United States involved the lack of Mexican government labor inspectors. According to Galarza, "In 1943, ten Mexican labor inspectors were assigned to ensure contract compliance throughout the United States; most were assigned to the Southwest and two were responsible for the northwestern area."[52] The lack of inspectors made the policing of pay and working conditions in the Northwest extremely difficult. The farmers set up powerful collective bodies like the Associated Farmers Incorporated of Washington with a united goal of keeping pay down and any union agitators or communists out of the fields.[53] The Associated Farmers used various types of law enforcement officials to keep "order" including privatized law enforcement officers, the state highway patrol, and even the National Guard.[54]

Another difference is the proximity, or not, to the Mexican border. In the Southwest, employers could easily threaten braceros with deportation knowing the ease with which new braceros could replace them. However, in the Northwest due to the much farther distance and cost associated with travel made threats of deportation harder to follow through with. Braceros in the Northwest could not easily skip out on their contracts due to the lack of a prominent Mexican-American community which would allow for them to blend in and not have to return to Mexico as so many of their counterparts in the Southwest chose to do and also the lack of proximity to the border.[55]

Knowing this difficulty, the Mexican consulate in Salt Lake City, and later the one in Portland, Oregon, encouraged workers to protest their conditions and advocated on their behalf much more than the Mexican consulates did for braceros in the Southwest.[56] Combine all these reasons together and it created a climate where braceros in the Northwest felt they had no other choice, but to strike in order for their voices to be heard.

Braceros met the challenges of discrimination and exploitation by finding various ways in which they could resist and attempt to improve their living conditions and wages in the Pacific Northwest work camps. Over two dozen strikes were held in the first two years of the program. One common method used to increase their wages was by "loading sacks" which consisted of braceros loading their harvest bags with rock in order to make their harvest heavier and therefore be paid more for the sack.[57] Also, braceros learned that timing was everything. Strikes were more successful when combined with work stoppages, cold weather, and a pressing harvest period.[58] The notable strikes throughout the Northwest proved that employers would rather negotiate with braceros than to deport them, employers had little time to waste as their crops needed to be harvested and the difficulty and expense associated with the bracero program forced them to negotiate with braceros for fair wages and better living conditions.[59]

Braceros were also discriminated and segregated in the labor camps. Some growers went to the extent of building three labor camps, one for whites, one for blacks, and the one for Mexicans.[60] The living conditions were horrible, unsanitary, and poor. For example, in 1943 in Grants Pass, Oregon, 500 braceros suffered food poisoning, one of the most severe cases reported in the Northwest. This detrition of the quality and quantity of food persisted into 1945 until the Mexican government intervened.[61] Lack of food, poor living conditions, discrimination, and exploitation led braceros to become active in strikes and to successfully negotiate their terms.

[62]== Role of women and impact on families == The role of women in the bracero movement was often that of the homemaker, the dutiful wife who patiently waited for their men; cultural aspects also demonstrate women as a deciding factor for if men answered to the bracero program and took part in it. Women and families left behind were also often seen as threats by the US government because of the possible motives for the full migration of the entire family.[63]

Romantic relationships

Bracero men's prospective in-laws were often wary of men who had a history of abandoning wives and girlfriends in Mexico and not coming back from the U.S. or not reaching out when they were back in the country. The women's families were not persuaded then by confessions and promises of love and good wages to help start a family and care for it.[63] As a result, bracero men who wished to marry had to repress their longings and desires as did women to demonstrate to the women's family that they were able to show strength in emotional aspects, and therefore worthy of their future wife.[63]

Due to gender roles and expectations, bracero wives and girlfriends left behind had the obligation to keep writing love letters, to stay in touch, and to stay in love while bracero men in the U.S. did not always respond or acknowledge them.[63] Married women and young girls in relationships were not supposed to voice their concerns or fears about the strength of their relationship with bracero men, and women were frowned upon if they were to speak on their sexual and emotional longings for their men as it was deemed socially, religiously, and culturally inappropriate.[63]

Women as deciding factors for men in bracero program integration

The Bracero Program was an attractive opportunity for men who wished to either begin a family with a head start with American wages,[64] or to men who were already settled and who wished to expand their earnings or their businesses in Mexico.[65] As such, women were often those to whom both Mexican and US governments had to pitch the program to.[63] Local Mexican government was well aware that whether male business owners went into the program came down to the character of their wives; whether they would be willing to take on the family business on their own in place of their husbands or not.[63] Workshops were often conducted in villages all over Mexico open to women for them to learn about the program and to encourage their husbands to integrate into it as they were familiarized with the possible benefits of the program [63]

US government censorship of family contact

As men stayed in the U.S., wives, girlfriends, and children were left behind often for decades.[63] Bracero men searched for ways to send for their families and saved their earnings for when their families were able to join them. In the U.S., they made connections and learned the culture, the system, and worked to found a home for a family.[63] The only way to communicate their plans for their families' futures was through mail in letters sent to their women. These letters went through the US postal system and originally they were inspected before being posted for anything written by the men indicating any complaints about unfair working conditions.[63] However, once it became known that men were actively sending for their families to permanently reside in the US, they were often intercepted, and many men were left with no responses from their women.[63] Permanent settlement of bracero families was feared by the US, as the program was originally designed as a temporary work force which would be sent back to Mexico eventually.[63]

Aftermath

After the 1964 termination of the Bracero Program, the A-TEAM, or Athletes in Temporary Employment as Agricultural Manpower, program of 1965 was meant to simultaneously deal with the resulting shortage of farmworkers and a shortage of summer jobs for teenagers.[66] More than 18,000 17-year-old high school students were recruited to work on farms in Texas and California. Only 3,300 ever worked in the fields, and many of them quickly quit or staged strikes because of the poor working conditions, including oppressive heat and decrepit housing.[66] The program was cancelled after the first summer.

Significance and effects

The Catholic Church in Mexico was opposed to the Bracero Program, objecting to the separation of husbands and wives and the resulting disruption of family life; to the supposed exposure of migrants to vices such as prostitution, alcohol, and gambling in the United States; and to migrants' exposure to Protestant missionary activity while in the United States.[67][68] Starting in 1953, Catholic priests were assigned to some bracero communities,[67] and the Catholic Church engaged in other efforts specifically targeted at braceros.[68]

Labor unions that tried to organize agricultural workers after World War II targeted the Bracero Program as a key impediment to improving the wages of domestic farm workers.[69] These unions included the National Farm Laborers Union (NFLU), later called the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), headed by Ernesto Galarza, and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), AFL-CIO. During his tenure with the Community Service Organization, César Chávez received a grant from the AWOC to organize in Oxnard, California, which culminated in a protest of domestic U.S. agricultural workers of the U.S. Department of Labor's administration of the program.[69] In January 1961, in an effort to publicize the effects of bracero labor on labor standards, the AWOC led a strike of lettuce workers at 18 farms in the Imperial Valley, an agricultural region on the California-Mexico border and a major destination for braceros.[70]

Prior to the end of the Bracero Program in 1964, The Chualar Bus Crash in Salinas, California made headlines illustrating just how harsh braceros situations were in California. In the accident 31 braceros lost their lives in a collision with a train and a bracero transportation truck. This particular accident led activist groups from agriculture and the cities to come together and strongly oppose the Bracero Program.[71] According to Manuel Garcia y Griego, a political scientist and author of The Importation of Mexican Contract Laborers to the United States 1942–1964, the Contract-Labor Program "left an important legacy for the economies, migration patterns, and politics of the United States and Mexico". Griego's article discusses the bargaining position of both countries, arguing that the Mexican government lost all real bargaining-power after 1950. In addition to the surge of activism in American migrant labor the Chicano Movement was now in the forefront creating a united image on behalf of the fight against the Bracero Program.

The end of the Bracero Program in 1964 was followed by the rise to prominence of the United Farm Workers (UFW) and the subsequent transformation of American migrant labor under the leadership of César Chávez, Gilbert Padilla, and Dolores Huerta. Newly formed labor unions (sponsored by Chávez and Huerta), namely the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, were responsible for series of public demonstrations including the Delano grape strike. These efforts demanded change for labor rights, wages and the general mistreatment of workers that had gained national attention with the Bracero Program. Change ensued with the UFW championing a 40% wage increase for grape farm laborers nationwide.[72] While the federal minimum wage remained at $1.25 per hour, laborers operating under the grape contract made $1.50.[72] In order to avoid increased wages, farmers who formerly employed braceros would later turn to the mechanization of labor-intensive tasks.

Recent scholarship illustrates that the program generated controversy in Mexico from the outset. Mexican employers and local officials feared labor shortages, especially in the states of west-central Mexico that traditionally sent the majority of migrants north (Jalisco, Guanajuato, Michoacan, Zacatecas). The Catholic Church warned that emigration would break families apart and expose braceros to Protestant missionaries and to labor camps where drinking, gambling, and prostitution flourished. Others deplored the negative image that the braceros' departure produced for the Mexican nation. The political opposition even used the exodus of braceros as evidence of the failure of government policies, especially the agrarian reform program implemented by the post-revolutionary government in the 1930s.[73] Because of labor shortage concerns, the administration of president Ávila Camacho declared in 1942 that laborers from Jalisco, Guanajuato and Michoacan were ineligible to qualify as braceros. By 1944, some Jalisco and Michoacan laborers had found ways to evade the restrictions placed on them. They applied for state (not federal) government-issued provisional passports with which they entered the United States. In response, the Mexican federal government instructed state governments to ban the issuance of provisional passports to anyone who they deemed to fit the profile of a potential Bracero Program applicant. State governments were further instructed to distribute pamphlets warning that wages incurred by working in the U.S. illegally were not subject to protections contained in bracero contracts. Despite state government protests about the effects this would have on agricultural production, the federal Bracero ban on laborers from the three provinces was lifted by the Mexican government in 1946. [74]

Some historians like Michael Snodgrass and Deborah Cohen demonstrate why the program proved popular among so many migrants, for whom seasonal work in the US offered great opportunities, despite the poor conditions they often faced in the fields and housing camps. They saved money, purchased new tools or used trucks, and returned home with new outlooks and with a greater sense of dignity. Social scientists doing field work in rural Mexico at the time observed these positive economic and cultural effects of bracero migration.[75] The bracero program looked different from the perspective of the participants rather than from the perspective of its many critics in the U.S. and Mexico.

A 1980 Congressional Research Service report found that the Bracero Program was "instrumental" in significantly reducing illegal immigration by the mid-1950s.[76] The end of the program saw a rise in Mexican legal immigration between 1963 and 1972, as many Mexican men who had already lived in the United States chose to return, bringing along their families.[77] The dissolution of the Bracero program also saw a rise in undocumented immigration, despite the efforts of Operation Wetback, and American growers hired increasing numbers of undocumented migrants.[78]

The aftermath of the Bracero Program's effect on labor conditions for agricultural workers continues to be debated. On one hand, the end of the program allowed workers to unionize and facilitated victories made by labor organizations and other individuals. A key victory for these former braceros was the abolition of the short-handed hoe, el cortito, spurred by the efforts of American lawyer Maurice Jordan. Jordan was successfully able to win a case against California growers, claiming that the tool did not increase crop yield and caused several health issues for workers.[79]

However, the unionization efforts of the United Farm Workers, as popular as they were, were increasingly challenged by farm owners in the 1970s. Employers would pit unions against one another as they increasingly hired workers from the Teamster union, for example, that challenged the earlier work done by the UFW to achieve favorable contracts.[80] Furthermore, union participation has decreased among many farmworkers, reaching a 90% decline from 1975 to 2000, consequently lowering the bargaining power of these organizations.[81]

Some consider the H-2A visa program to be a repeat of the abuses of the Bracero Program where workers report dangerous conditions. For example, a blueberry farm worker in Washington died in August 2017 for reported 12-hour shifts under hot conditions to meet production quotas.[82]

A 2018 study published in the American Economic Review found that the Bracero program did not have any adverse impact on the labor market outcomes of American-born farm workers. The study found that ending the Bracero program did not raise wages or employment for American-born farm workers.[5] A 2023 study in the American Economic Journal found that the termination of the program had adverse economic effects on American farmers and prompted greater farm mechanization.[6]

In popular culture

- Woody Guthrie's poem "Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)", set to music by Martin Hoffman, commemorates the deaths of 28 braceros being repatriated to Mexico in January 1948. The song has been recorded by dozens of folk artists.

- Protest singer Phil Ochs's song "Bracero" focuses on the exploitation of the Mexican workers in the program.

- A minor character in the 1948 Mexican film Nosotros los Pobres wants to become a bracero.

- The 1949 film Border Incident explores two federal agents' efforts to end an illegal bracero-smuggling operation.[83]

- Famed satirist Tom Lehrer wrote the song "George Murphy" about Senator George Murphy in response to an infamous racist gaffe referring to Mexican labor, which included the lines "Should Americans pick crops? George says "No" / 'Cause no-one but a Mexican would stoop so low / And after all, even in Egypt, the pharaohs / Had to import Hebrew braceros".[84]

- The 2010 documentary Harvest of Loneliness describes the history of the bracero program. It includes interviews with several former braceros and family members, and with labor historian Henry Anderson.

- A Convenient Truth (2014) urges viewers not to let their governments repeat "the follies" of the Braceros program, during the end credits.

- In 1953, Pedro Infante recorded Canto del Bracero under Peerlees label.

Exhibitions and collections

In October 2009, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History opened a bilingual exhibition titled, "Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program, 1942–1964." Through photographs and audio excerpts from oral histories, this exhibition examined the experiences of bracero workers and their families while providing insight into the history of Mexican Americans and historical context to today's debates on guest worker programs. The exhibition included a collection of photographs taken by photojournalist Leonard Nadel in 1956, as well as documents, objects, and an audio station featuring oral histories collected by the Bracero Oral History Project. The exhibition closed on January 3, 2010. The exhibition was converted to a traveling exhibition in February 2010 and traveled to Arizona, California, Idaho, Michigan, Nevada, and Texas under the auspices of Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service.[85]

See also

- Bracero Selection Process

- 1917 Bath Riots

- Maquiladora

- Operation Wetback

- Chualar Bus Incident

- Mexican Repatriation

- Bracero Monument

- Rio Vista Bracero Reception Center

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Calavita, Kitty (1992). Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I. N. S. New York: Quid Pro, LLC. p. 1. ISBN 0-9827504-8-X.

- ^ "Bracero History Archive | About". braceroarchive.org. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Koestler, Fred L. "Bracero Program". tshaonline.org. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "SmallerLarger Bracero Program Begins, April 4, 1942". Student Resources in Context. Gale, Cengage Learning. Retrieved March 17, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Clemens, Michael A.; Lewis, Ethan G.; Postel, Hannah M. (June 2018). "Immigration Restrictions as Active Labor Market Policy: Evidence from the Mexican Bracero Exclusion". American Economic Review. 108 (6): 1468–1487. doi:10.1257/aer.20170765. ISSN 0002-8282. PMC 6040835. PMID 30008480.

We find that bracero exclusion failed to raise wages or substantially raise employment for domestic workers in the sector.

- ^ a b San, Shmuel (2023). "Labor Supply and Directed Technical Change: Evidence from the Termination of the Bracero Program in 1964". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 15 (1): 136–163. doi:10.1257/app.20200664. ISSN 1945-7782.

- ^ a b c Ngai, Mae (2004). Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 139. ISBN 978-0-691-12429-2.

- ^ Loza, Mireya (2016), "UNIONIZING THE IMPOSSIBLE: Alianza de Braceros Nacionales de México en los Estados Unidos", Defiant Braceros, How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual, and Political Freedom, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 97–136, ISBN 978-1-4696-2976-6, JSTOR 10.5149/9781469629773_loza.7, retrieved August 27, 2024

- ^ McWilliams, Carey. North From Mexico: The Spanish Speaking People of the United States.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Bracero Program – Rural Migration News | Migration Dialogue". migration.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "World War II Homefront Era: 1940s: Bracero Program Establishes New Migration Patterns | Picture This". picturethis.museumca.org. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Gamboa, Erasmo (2016). Bracero Railroaders: The Forgotten World War II Story of Mexican Workers in the U.S. West. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99832-9. JSTOR j.ctvcwn55d.

- ^ "S. 984 - Agricultural Act, 1949 Amendment of 1951". P.L. 82-78 ~ 65 Stat. 119. Congress.gov. July 12, 1951.

- ^ Truman, Harry S. (July 13, 1951). "Special Message to the Congress on the Employment of Agricultural Workers from Mexico - July 13, 1951". Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Service. pp. 389–393.

- ^ Truman, Harry S. (June 25, 1952). "Veto of Bill To Revise the Laws Relating to Immigration, Naturalization, and Nationality - June 25, 1952". Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Service. pp. 441–447.

- ^ "H.R. 5678 - Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952". P.L. 82-414 ~ 66 Stat. 163. Congress.gov. June 27, 1952.

- ^ "H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers". USCIS. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Bath Riots: Indignity Along the Mexican Border". NPR. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Molina, Natalia (2011). "Borders, Laborers, and Racialized Medicalization Mexican Immigration and US Public Health Practices in the 20th Century". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (6): 1024–1031. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.300056. PMC 3093266. PMID 21493932.

- ^ "Labor Groups Oppose Bracero Law Features". Archives.TexasObserver.org. Texas Observer. March 28, 1955. p. 7. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Scruggs, Otey M. (August 1, 1963). "Texas and the Bracero Program, 1942–1947". Pacific Historical Review. 32 (3): 251–64. doi:10.2307/4492180. JSTOR 4492180.

- ^ "Mexico - Migration of Agricultural Workers - August 4, 1942" [56 Stat. 1759, E.A.S. 278 - No. 312]. United States Statutes at Large. LVI (U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 56 (1942), 77th Congress, Session II). United States Library of Congress: 1759–1769. August 4, 1942.

- ^ average for '43, 45–46 calculated from total of 220,000 braceros contracted '42-47, cited in Navarro, Armando, Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán (2005)

- ^ average calculated from total of 401,845 braceros under the period of negotiated administrative agreements, cited in Navarro, Armando, Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán (2005)

- ^ Data 1951–67 cited in Gutiérrez, David Gregory, Between two worlds (1996)

- ^ a b "Braceros: History, Compensation – Rural Migration News | Migration Dialogue". migration.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ Northwest Farm News, February 3, 1944. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 80.

- ^ Gonzales-Berry, Erlinda (2012). Mexicanos in Oregon: Their Stories, Their Lives. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. p. 46.

- ^ Narrative, June 1944, Preston, Idaho, Box 52, File: Idaho, GCRG224, NA. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 81.

- ^ Narrative, July 1944, Rupert, Idaho, Box 52, File: Idaho; Narrative, October 1944, Lincoln, Idaho; all in GCRG224, NA. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", pp. 81–82.

- ^ Narrative, October 1944, Sugar City, Idaho, Box 52, File: Idaho; Narrative, October 1944, Lincoln, Idaho; all in GCRG224, NA. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 82.

- ^ Visitation Reports, Walter E. Zuger, Walla Walla County, June 12, 1945, EFLR, WSUA. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 84.

- ^ Idaho Daily Statesman, June 8, 1945. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 84.

- ^ Jimenez Sifuentez, Mario (2016). Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 26.

- ^ Idaho Daily Statesman, June 29, 1945. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 84.

- ^ Idaho Daily Statesman, July 11, 14, 1945. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 84.

- ^ Daily Statesman, October 5, 1945. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 82.

- ^ Annual Report of State Supervisor of Emergency Farm Labor Program 1945, Extension Service, p. 56, OSU. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 82.

- ^ Marshall, Maureen E. Wenatchee's Dark Past. Wenatchee, Wash: The Wenatchee World, 2008.

- ^ Jerry Garcia; Gilberto Garcia. "Chapter 3: Japanese and Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest, 1900–1945". Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest. pp. 85–128.

- ^ Roger Daniels (1993). Prisoners Without Trials: Japanese Americans in World War II. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 74. Cited in Garcia and Garcia, Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest, p. 104.

- ^ College of Washington and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperating, Specialist Record of County Visit, Columbia County, Walter E. Zuger, Assistant State Farm Labor Supervisor, July 21–22, 1943. Cited in Garcia and Garcia, Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest, p. 112.

- ^ "Cannery Shut Down By Work Halt." Walla Walla Union-Bulletin, July 22, 1943. Cited in Garcia and Garcia, Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest, p. 113.

- ^ College of Washington and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperating, Specialist Record of County Visit, Columbia County, Walter E. Zuger, Assistant State Farm Labor Supervisor, July 21–22, 1943. Cited in Garcia and Garcia, Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest, p. 113.

- ^ Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", pp. 74–75.

- ^ Rasmussen, Wayne D. (1951). "A History of the Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program, 1943-47" [Letter, War Food Administrator to Secretary of State, June 15, 1943]. Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Economics. p. 229. OCLC 16762793.

- ^ Rasmussen, Wayne D. (1951). "A History of the Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program, 1943-47" [Memorandum transmitted to Brig. Gen. Philip G. Burton by John Willard Carigan, September 23, 1944]. Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Economics. p. 230. OCLC 16762793.

- ^ Rasmussen, Wayne D. (1951). "A History of the Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program, 1943-47" [Letter, Howard A. Preston to Chief of Operations, Chicago, Illinois, Sept. 24, 1945]. Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Agricultural Economics. p. 232. OCLC 16762793.

- ^ a b Osorio, Jennifer (2005). "Proof of a Life Lived: The Plight of the Braceros and What It Says About How We Treat Records". Archival Issues. 29 (2): 95–103. ISSN 1067-4993. JSTOR 41102104.

- ^ "U.S. INVESTIGATES BRACERO PROGRAM; Labor Department Checking False-Record Report Rigging Is Denied Wage Rates Vary". The New York Times. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Ernesto Galarza, "Personal and Confidential Memorandum". pp. 8–9. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 75.

- ^ Northwest Farm News, January 13, 1938. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 76.

- ^ Idaho Falls Post Register, September 12, 1938; Yakima Daily Republic, August 25, 1933. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 76.

- ^ Mario Jimenez Sifuentez (2016). Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 28.

- ^ Ernesto Galarza (1964). Merchants of Labor: The Mexican Bracero Story. Cited in Gamboa, "Mexican Labor and World War II", p. 77.

- ^ Mario Jimenez Sifuentez (2016). Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 25.

- ^ Erasmo Gamboa (1990). Mexican Labor & World War II: Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942–1947. Seattle: University of Washington. p. 85.

- ^ Mario Jimenez Sifuentez. Of Forests and Fields. pp. 28–29

- ^ Robert Bauman (2005). "Jim Crow in the Tri-Cities, 1943–1950". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 96 (3): 126.

- ^ Erasmo Gamboa (1981). "Mexican Migration into Washington State: A History, 1940–1950". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 72 (3): 125.

- ^ Rosas, Ana Elizabeth (August 2011). "Breaking the Silence: Mexican Children and Women's Confrontation of Bracero Family Separation, 1942-64". Gender & History. 23 (2): 382–400. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2011.01644.x. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rosas, Ana Elizabeth (2014). Abrazando El Espíritu: Bracero Families Confront the US-Mexico Border. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520282667. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt13x1hjj. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Navarro, Moisés González (January 1, 1994). Los extranjeros en México y los mexicanos en el extranjero, 1821-1970: Tomo 3, 1910-1970 (1 ed.). El Colegio de México. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3f8ns4.6. ISBN 978-607-564-044-0. JSTOR j.ctv3f8ns4.

- ^ Cardoso, Lawrence A. (May 1, 2019). Mexican Emigration to the United States, 1897–1931. University of Arizona Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvss3xzr.9. ISBN 978-0-8165-4029-7. JSTOR j.ctvss3xzr. S2CID 241262377.

- ^ a b Arellano, Gustavo (August 23, 2018). "When The U.S. Government Tried To Replace Migrant Farmworkers With High Schoolers". NPR. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Richard B. Craig, The Bracero Program: Interest Groups and Foreign Policy (University of Texas Press, 1971).

- ^ a b David Fitzgerald, Uncovering the Emigration Policies of the Catholic Church in Mexico, Migration Police Institute (May 21, 2009).

- ^ a b Ferris, Susan and Sandoval, Ricardo (1997). The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement

- ^ Los Angeles Times, January 23, 1961 "Lettuce Farm Strike Part of Deliberate Union Plan"

- ^ "A Town Full of Dead Mexicans: The Salinas Valley Bracero Tragedy of 1963, the End of the Bracero Program, and the Evolution of California's Chicano Movement". The Western Historical Quarterly. 44 (2): 124–143. July 2013. doi:10.2307/westhistquar.44.2.0124.

- ^ a b "Mexican Braceros and US Farm Workers | Wilson Center". www.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Snodgrass, "The Bracero Program," pp.83-88

- ^ García, Alberto (January 17, 2023). Abandoning Their Beloved Land. University of California Press. pp. 40–55. doi:10.2307/j.ctv34j7mrm. ISBN 978-0-520-39024-9.

- ^ Snodgrass, "Patronage and Progress," pp.252-61; Michael Belshaw, A Village Economy: Land and People of Huecorio (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967)

- ^ Congressional Research Service (1980), Temporary Worker Programs: Background and Issues, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 41, retrieved May 12, 2024 – via HathiTrust

- ^ Portes, Alejandro (March 1, 1974). "Return of the wetback". Society. 11 (3): 40–46. doi:10.1007/BF02695162. ISSN 1936-4725. S2CID 143986760.

- ^ Zatz, Marjorie S.; Calavita, Kitty; Gamboa, Erasmo (1993). "Using and Abusing Mexican Farmworkers: The Bracero Program and the INS". Law & Society Review. 27 (4): 851. doi:10.2307/3053955. JSTOR 3053955.

- ^ Murray, Douglas L. (October 1982). "The Abolition of El Cortito, the Short-Handled Hoe: A Case Study in Social Conflict and State Policy in California Agriculture". Social Problems. 30 (1): 26–39. doi:10.2307/800182. ISSN 0037-7791. JSTOR 800182.

- ^ CHAVEZ, CESAR (1976). "The California Farm Workers' Struggle". The Black Scholar. 7 (9): 16–19. doi:10.1080/00064246.1976.11413833. ISSN 0006-4246. JSTOR 41066045.

- ^ "Labor Relations in California Agriculture: 1975-2000 -- Philip Martin - Changing Face | Migration Dialogue". migration.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Bacon, David (June 1, 2018). "'You Came Here to Suffer'". Progressive.org. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Auerbach, Jonathan (2008). "Noir Citizenship: Anthony Mann's "Border Incident"". Cinema Journal. 47 (4): 102–120. doi:10.1353/cj.0.0021. ISSN 0009-7101. JSTOR 20484414. S2CID 144835225.

- ^ tomlehrer. "George Murphy (incl. The George Murphy Campaign Song and addenda)". Tom Lehrer Songs. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942–1964 / Cosecha Amarga Cosecha Dulce: El Programa Bracero 1942–1964". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

Bibliography

- Driscoll, Barbara A. (1999). The Tracks North: The Railroad Bracero Program of World War II. Austin, Texas: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas at Austin. ISBN 978-0292715929. LCCN 97049865. OCLC 241413991.

- Deborah Cohen, Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

- Hirsch, Hans G. (1967). "Termination of the Bracero Program: Foreign Economic Aspects". Internet Archive. Foreign Agricultural Economic Report, No. 34. Washington, D.C.: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. OCLC 2330552.

- Koestler, Fred L. (February 22, 2010). "Bracero Program". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- McElroy, Robert C. (June 1965). "Termination of the Bracero Program: Some Effects on Farm Labor and Migrant Housing Needs". National Agricultural Library Digital Collections. Agricultural Economic Report, No. 77. Washington, D.C.: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. OCLC 14819771.

- Don Mitchell, They Saved the Crops: Labor, Landscape, and the Struggle Over Industrial Farming in Bracero-Era California. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

- Ana Elizabeth Rosas, Abrazando el Espíritu: Bracero Families Confront the US-Mexico Border. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014.

- Scruggs, Otey M. (1963). "Texas and the Bracero Program, 1942–1947". Pacific Historical Review. 32 (3): 251–264. doi:10.2307/4492180. JSTOR 4492180.

- Michael Snodgrass, "The Bracero Program, 1942–1964," in Beyond the Border: The History of Mexican-U.S. Migration, Mark Overmyer-Velásquez, ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 79–102.

- Michael Snodgrass, "Patronage and Progress: The bracero program from the Perspective of Mexico," in Workers Across the Americas: The Transnational Turn in Labor History, Leon Fink, ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 245–266.

- Flores, Lori A. (2016). Grounds for dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, and the California farmworker movement. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300196962. OCLC 906878123.

External links

Media related to Bracero program at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bracero program at Wikimedia Commons- The Bracero Project

- Los Braceros: Strong Arms to Aid the USA – Public Television Program

- Braceros in Oregon Photograph Collection

- Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942–1964 An online exhibition from the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

- University of Texas El Paso Oral History Archive

- "1942: Bracero Program". LOC Research Guides. United States Library of Congress.

- "Bracero Program: Photographs of the Mexican Agricultural Labor Program ~ 1951-1964". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Bracero Program - USCIS History Library. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. January 7, 2020.

- "Braceros in Oregon Photograph Collection." Oregon State University, Special Collections and Archives Research Center.

- "Why Braceros?". Internet Archive. Wilding-Butler Division of Wilding, Inc. 1959. OCLC 1232500309.

- Bracero Archive - a project of the Roy Rosenzwieg Center for History and New Media, George Mason University, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Brown University, and The Institute of Oral History at the University of Texas at El Paso.

- Agricultural labor in the United States

- Agriculture in California

- Labor history of the United States

- Labor relations in California

- History of labor relations in the United States

- History of immigration to the United States

- Economic history of Mexico

- Economic history of the United States

- History of North America

- History of Mexican Americans

- Mexico–United States relations

- United States home front during World War II

- Government agencies established in 1942

- 1942 in international relations

- 1942 in Mexico

- 1942 in the United States

- 1964 disestablishments

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !