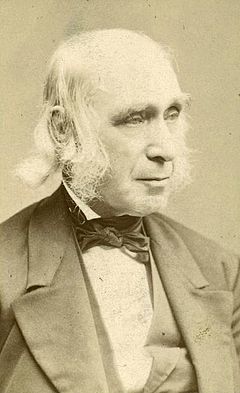

Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Amos Bronson Alcox November 29, 1799 Wolcott, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 1888 (aged 88) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

Amos Bronson Alcott (/ˈɔːlkət/; November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and avoided traditional punishment. He hoped to perfect the human spirit and, to that end, advocated a plant-based diet. He was also an abolitionist and an advocate for women's rights.

Born in Wolcott, Connecticut, in 1799, Alcott had only minimal formal schooling before attempting a career as a traveling salesman. Worried that the itinerant life might have a negative impact on his soul, he turned to teaching. His innovative methods, however, were controversial, and he rarely stayed in one place very long. His most well-known teaching position was at the Temple School in Boston. His experience there was turned into two books: Records of a School and Conversations with Children on the Gospels. Alcott became friends with Ralph Waldo Emerson and became a major figure in transcendentalism. His writings on behalf of that movement, however, are heavily criticized for being incoherent. Based on his ideas for human perfection, Alcott founded Fruitlands, a transcendentalist experiment in community living. The project failed after seven months. Alcott and his family struggled financially for most of his life. Nevertheless, he continued focusing on educational projects and opened a new school at the end of his life in 1879. He died in 1888.

Alcott married Abby May in 1830, and they had four surviving children, all daughters. Their second was Louisa May, who fictionalized her experience with the family in her novel Little Women in 1868.

Life and work

Early life

A native New Englander, Amos Bronson Alcott was born in Wolcott, Connecticut (then recently renamed from "Farmingbury") on November 29, 1799.[1] His parents were Joseph Chatfield Alcott and Anna Bronson Alcott. The family home was in an area known as Spindle Hill, and his father, Joseph Alcox, traced his ancestry to colonial-era settlers in eastern Massachusetts. The family originally spelled their name "Alcock", later changed to "Alcocke" then "Alcox". Amos Bronson, the oldest of eight children, later changed the spelling to "Alcott" and dropped his first name.[2] At age six, young Bronson began his formal education in a one-room schoolhouse in the center of town but learned how to read at home with the help of his mother.[3] The school taught only reading, writing, and spelling, and he left this school at the age of 10.[4] At age 13, his uncle, Reverend Tillotson Bronson, invited Alcott into his home in Cheshire, Connecticut, to be educated and prepared for college. Bronson gave it up after only a month[5] and was self-educated from then on.[6] He was not particularly social and his only close friend was his neighbor and second cousin William Alcott, with whom he shared books and ideas.[7] Bronson Alcott later reflected on his childhood at Spindle Hill: "It kept me pure ... I dwelt amidst the hills ... God spoke to me while I walked the fields."[8] Starting at age 15, he worked for clockmaker Seth Thomas[9] in the nearby town of Plymouth.[10]

At age 17, Alcott passed the exam for a teaching certificate but had trouble finding work as a teacher.[9] Instead, he left home and became a traveling salesman in the American South,[6] peddling books and merchandise. He hoped the job would earn him enough money to support his parents, "to make their cares, and burdens less ... and get them free from debt", though he soon spent most of his earnings on a new suit.[11] At first, he thought it an acceptable occupation but soon worried about his spiritual well-being. In March 1823, Alcott wrote to his brother: "Peddling is a hard place to serve God, but a capital one to serve Mammon."[12] Near the end of his life, he fictionalized this experience in his book, New Connecticut, originally circulated only among friends before its publication in 1881.[13]

Early career and marriage

By the summer of 1823, Alcott returned to Connecticut in debt to his father, who had bailed him out after his last two unsuccessful sales trips.[14] He took a job as a schoolteacher in Cheshire with the help of his Uncle Tillotson.[15] He quickly set about reforming the school. He added backs to the benches on which students sat, improved lighting and heating, de-emphasized rote learning, and provided individual slates to each student—paid for by himself.[16] Alcott had been influenced by educational philosophy of the Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and even renamed his school "The Cheshire Pestalozzi School".[15]

His style attracted the attention of Samuel Joseph May, who introduced Alcott to his sister Abby May. She called him, "an intelligent, philosophic, modest man" and found his views on education "very attractive".[16] Locals in Cheshire were less supportive and became suspicious of his methods. Many students left and were enrolled in the local common school or a recently reopened private school for boys.[17] On November 6, 1827, Alcott started teaching in Bristol, Connecticut, still using the same methods he used in Cheshire, but opposition from the community surfaced quickly;[18] he was unemployed by March 1828.[19] He moved to Boston on April 24, 1828, and was immediately impressed, referring to the city as a place "where the light of the sun of righteousness has risen".[20] He opened the Salem Street Infant School two months later on June 23.[21] Abby May applied as his teaching assistant; instead, the couple were engaged, without consent of the family.[22] They were married at King's Chapel on May 22, 1830; he was 30 years old and she was 29.[23] Her brother conducted the ceremony and a modest reception followed at her father's house.[24] After their marriage the Alcotts moved to 12 Franklin Street in Boston, a boarding house run by a Mrs. Newall.[25] Around this time, Alcott also first expressed his public disdain for slavery. In November 1830, he and William Lloyd Garrison founded what he later called a "preliminary Anti-Slavery Society", though he differed from Garrison as a nonresistant.[26] Alcott became a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee.[27]

Attendance at Alcott's school was falling when a wealthy Quaker named Reuben Haines III proposed that he and educator William Russell start a new school in Pennsylvania,[24] associated with the Germantown Academy. Alcott accepted and he and his newly pregnant wife set forth on December 14.[28] The school was established in Germantown[29] and the Alcotts were offered a rent-free home by Haines. Alcott and Russell were initially concerned that the area would not be conducive to their progressive approach to education and considered establishing the school in nearby Philadelphia instead.[28] Unsuccessful, they went back to Germantown, though the rent-free home was no longer available and the Alcotts instead had to rent rooms in a boarding-house.[30] It was there that their first child, a daughter they named Anna Bronson Alcott, was born on March 16, 1831,[24] after 36 hours of labor.[30] By the fall of that year, their benefactor Haines died suddenly and the Alcotts again suffered financial difficulty. "We hardly earn the bread", wrote Abby May to her brother, "[and] the butter we have to think about."[31]

The couple's only son was born on April 6, 1839, but lived only a few minutes. The mother recorded: "Gave birth to a fine boy full grown perfectly formed but not living".[32] It was in Germantown that the couple's second daughter was born. Louisa May Alcott was born on her father's birthday, November 29, 1832, at a half-hour past midnight.[33] Bronson described her as "a very fine healthful child, much more so than Anna was at birth".[34] The Germantown school, however, was faltering; soon only eight pupils remained.[35] Their benefactor Haines died before Louisa's birth. He had helped recruit students and even paid tuition for some of them. As Abby wrote, his death "has prostrated all our hopes here".[36] On April 10, 1833, the family moved to Philadelphia,[35] where Alcott ran a day school. As usual, Alcott's methods were controversial; a former student later referred to him as "the most eccentric man who ever took on himself to train and form the youthful mind".[37] Alcott began to believe Boston was the best place for his ideas to flourish. He contacted theologian William Ellery Channing for support. Channing approved of Alcott's methods and promised to help find students to enroll, including his daughter Mary. Channing also secured aid from Justice Lemuel Shaw and Boston mayor Josiah Quincy Jr.[38]

Experimental educator

On September 22, 1834, Alcott opened a school of about 30 students, mostly from wealthy families.[39] It was named the Temple School because classes were held at the Masonic Temple on Tremont Street in Boston.[40] His assistant was Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, later replaced by Margaret Fuller. Mary Peabody Mann served as a French instructor for a time.[41] The school was briefly famous, and then infamous, because of Alcott's method of "discarding text-books and teaching by conversation", his questioning attitude toward the Bible, and his reception of "a colored girl" into his classes.[42]

Before 1830, primary and secondary teaching of writing consisted of rote drills in grammar, spelling, vocabulary, penmanship and transcription of adult texts. In that decade, however, progressive reformers such as Alcott, influenced by Pestalozzi, Friedrich Fröbel, and Johann Friedrich Herbart, began to advocate compositions based on students' own experiences. These reformers opposed beginning instruction with rules and preferred to have students learn to write by expressing their personal understanding of the events of their lives.

Alcott sought to develop instruction on the basis of self-analysis, with an emphasis on conversation and questioning rather than lecturing and drill. A similar interest in instructive conversation was shared by Abby May who, describing her idea of a family "post office" set up to curb potential domestic tension, said "I thought it would afford a daily opportunity for the children, indeed all of us, to interchange thought and sentiment".[43]

Alongside writing and reading, Alcott gave lessons in "spiritual culture", which included interpretation of the Gospels, and advocated object teaching in writing instruction.[44] He even went so far as to decorate his schoolroom with visual elements he thought would inspire learning: paintings, books, comfortable furniture, and busts or portraits of Plato, Socrates, Jesus, and William Ellery Channing.[40]

During this time, the Alcotts had another child. Born on June 24, 1835, she was named Elizabeth Peabody Alcott in honor of the teaching assistant at the Temple School.[45] By age three, however, her mother changed her name to Elizabeth Sewall Alcott, after her own mother,[46] perhaps because of the recent rupture between Bronson Alcott and Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.[47]

In July 1835, Peabody published her account as an assistant to the Temple School as Record of a School: Exemplifying the General Principles of Spiritual Culture.[41] While working on a second book, Alcott and Peabody had a falling out and Conversations with Children on the Gospels was prepared with help from Peabody's sister Sophia,[48] published at the end of December 1836.[39] Alcott's methods were not well received; many found his conversations on the Gospels close to blasphemous. For example, he asked students to question if Biblical miracles were literal and suggested that all people are part of God.[49] In the Boston Daily Advertiser, Nathan Hale criticized Alcott's "flippant and off hand conversation" about serious topics from the Virgin birth of Jesus to circumcision.[50] Joseph T. Buckingham called Alcott "either insane or half-witted" and "an ignorant and presuming charlatan".[51] The book did not sell well; a Boston lawyer bought 750 copies to use as waste paper.[52]

The Temple School was widely denounced in the press. Reverend James Freeman Clarke was one of Alcott's few supporters and defended him against the harsh response from Boston periodicals.[53] Alcott was rejected by most public opinion and, by the summer of 1837, he had only 11 students left and no assistant after Margaret Fuller moved to Providence, Rhode Island.[54] The controversy had caused many parents to remove their children and, as the school closed, Alcott became increasingly financially desperate.[42] Remaining steadfast to his pedagogy, a forerunner of progressive and democratic schooling, he alienated parents in a later "parlor school" by admitting an African American child to the class, whom he then refused to expel in the face of protests.

Transcendentalist

Beginning in 1836, Alcott's membership in the Transcendental Club put him in the company of such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Orestes Brownson and Theodore Parker.[55] He became a member at the club's second meeting and hosted its third.[50] A biographer of Emerson described the group as "the occasional meetings of a changing body of liberal thinkers, agreeing in nothing but their liberality".[56] Frederic Henry Hedge wrote similarly that "[t]here was no club in the strict sense ... only occasional meetings of like-minded men and women".[56] Alcott preferred the term "Symposium" for their group.[57]

In late April 1840, Alcott moved to the town of Concord[58] urged by Emerson. He rented a home for $50 a year within walking distance of Emerson's house. He named it Dove Cottage.[59] A supporter of his philosophies, Emerson offered to help Alcott with his writing. This proved a difficult task. For example, after several revisions of the essay "Psyche" (Alcott's account of how he educated his daughters), Emerson deemed it unpublishable.[60] Alcott also wrote a series patterned after the work of German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe which was published in the Transcendentalists' journal, The Dial. Emerson had written to Margaret Fuller, then editor, that Alcott's so-called "Orphic Sayings" might "pass muster & even pass for just & great",[58] but they were widely mocked as silly and unintelligible. Fuller herself disliked them, but did not want to hurt Alcott's feelings.[61] The following example appeared in the first issue:

Nature is quick with spirit. In eternal systole and diastole, the living tides course gladly along, incarnating organ and vessel in their mystic flow. Let her pulsations for a moment pause on their errands, and creation's self ebbs instantly into chaos and invisibility again. The visible world is the extremist wave of that spiritual flood, whose flux is life, whose reflux death, efflux thought, and conflux light. Organization is the confine of incarnation,—body the atomy of God.[62]

With financial support from Emerson,[63] and leaving his family in the care of his brother Junius,[64] Alcott departed Concord for a visit to England on May 8, 1842. There he met admirers Charles Lane and Henry C. Wright,[65] supporters of Alcott House, an experimental school outside London based on Alcott's Temple School methods.[63] The two men followed Alcott back to the United States and, in an early communitarian experiment, Lane and his son moved in with the Alcotts.[66]

Persuaded in part by Lane's abolitionist views, Alcott took a stand against President Tyler's plan to annex Texas as a slave territory and refused to pay his poll tax.[67] Abby May wrote in her journal on January 17, 1843, "A day of some excitement, as Mr. Alcott refused to pay his town tax ... After waiting some time to be committed [to jail], he was told it was paid by a friend. Thus we were spared the affliction of his absence and the triumph of suffering for his principles."[68] The incident inspired Henry David Thoreau, whose similar protest against the $1.50 poll tax led to a night in jail and his essay "Civil Disobedience".[69]

Fruitlands

Lane and Alcott collaborated on a major expansion of their educational theories into a Utopian society. Alcott, however, was still in debt and could not purchase the land needed for their planned community. In a letter, Lane wrote, "I do not see anyone to act the money part but myself."[70] In May 1843, he purchased a 90-acre (36 ha) farm in Harvard, Massachusetts.[71] Up front, he paid $1,500 of the total $1,800 value of the property; the rest was meant to be paid by the Alcotts over a two-year period.[72] They moved to the farm on June 1 and optimistically named it "Fruitlands" despite only ten old apple trees on the property.[71] In July, Alcott announced their plans in The Dial: "We have made an arrangement with the proprietor of an estate of about a hundred acres, which liberates this tract from human ownership".[71]

Their goal was to regain Eden, to find the formula for agriculture, diet, and reproduction that would provide the perfect way for the individual to live "in harmony with nature, the animal world, his fellows, himself, [and] his creator".[73] In order to achieve this, they removed themselves from the economy as much as possible and lived independently,[74] styling themselves a "consociate family".[71] Unlike a similar project named Brook Farm, the participants at Fruitlands avoided interaction with other local communities.[75] At first scorning animal labor as exploitative,[71] they found human spadework insufficient to their needs and eventually allowed some cattle to be "enslaved".[76] They banned coffee, tea, alcoholic drinks, milk, and warm bathwater.[77] As Alcott had published earlier, "Our wine is water, — flesh, bread; — drugs, fruits."[78] One member, Samuel Bower, "gave the community the reputation of refusing to eat potatoes because instead of aspiring toward the sky they grew downward in the earth",[79] For clothing, they prohibited leather, because animals were killed for it, as well as cotton, silk, and wool, because they were products of slave labor.[76] Alcott had high expectations, but was often away, attempting to recruit more members when the community most needed him.[80]

The experimental community was never successful, partly because most of the land was not arable.[81] Alcott lamented, "None of us were prepared to actualize practically the ideal life of which we dreamed. So we fell apart".[82] Its founders were often away as well; in the middle of harvesting, they left for a lecture tour through Providence, Rhode Island, New York City, and New Haven, Connecticut.[83] In its seven months, only 13 people joined, included the Alcotts and Lanes.[84] Other than Abby May and her daughters, only one other woman joined, Ann Page. One rumor is that Page was asked to leave after eating a fish tail with a neighbor.[85] Lane believed Alcott had misled him into thinking enough people would join the enterprise and developed a strong dislike for the nuclear family. He quit the project and moved to a nearby Shaker family with his son.[86] After Lane's departure, Alcott fell into a depression and could not speak or eat for three days.[87] Abby May thought Lane purposely sabotaged her family. She wrote to her brother, "All Mr. Lane's efforts have been to disunite us. But Mr. Alcott's ... paternal instincts were too strong for him."[88] When the final payment on the farm was owed, Sam May refused to cover his brother-in-law's debts, as he often did, possibly at Abby May's suggestion.[89] The experiment failed, the Alcotts had to leave Fruitlands.

The members of the Alcott family were not happy with their Fruitlands experience. At one point, Abby May threatened that she and their daughters would move elsewhere, leaving Bronson behind.[90] Louisa May Alcott, who was ten years old at the time, later wrote of the experience in Transcendental Wild Oats (1873): "The band of brothers began by spading garden and field; but a few days of it lessened their ardor amazingly."[91]

Return to Concord

In January 1844, Alcott moved his family to Still River, a village within Harvard[92] but, on March 1, 1845, the family returned to Concord to live in a home they named "The Hillside" (later renamed "The Wayside" by Nathaniel Hawthorne).[93] Both Emerson and Sam May assisted in securing the home for the Alcotts.[94] While living in the home, Louisa began writing in earnest and was given her own room.[95] She later said her years at the home "were the happiest years" of her life; many of the incidents in her novel Little Women (1868) are based on this period.[96] Alcott renovated the property, moving a barn and painting the home a rusty olive color, as well as tending to over six acres of land.[97] On May 23, 1845, Abby May was granted a sum from her father's estate which was put into a trust fund, granting minor financial security.[94] That summer, Bronson Alcott let Henry David Thoreau borrow his ax to prepare his home at Walden Pond.[98]

The Alcotts hosted a steady stream of visitors at The Hillside,[99] including fugitive slaves, which they hosted in secret as a station of the Underground Railroad.[100] Alcott's opposition to slavery also fueled his opposition to the Mexican–American War which began in 1846. He considered the war a blatant attempt to extend slavery and asked if the country was made up of "a people bent on conquest, on getting the golden treasures of Mexico into our hands, and of subjugating foreign peoples?"[101]

In 1848, Abby May insisted they leave Concord, which she called "cold, heartless, brainless, soulless". The Alcott family put The Hillside up for rent and moved to Boston.[102] There, next door to Peabody's book store on West Street, Bronson Alcott hosted a series based on the "Conversations" model by Margaret Fuller called "A Course on the Conversations on Man—his History, Resources, and Expectations". Participants, both men and women, were charged three dollars to attend or five dollars for all seven lectures.[103] In March 1853, Alcott was invited to teach fifteen students at Harvard Divinity School in an extracurricular, non-credit course.[104]

Alcott and his family moved back to Concord after 1857, where he and his family lived in the Orchard House until 1877. In 1860, Alcott was named superintendent of Concord Schools.[105]

Civil War years and beyond

Alcott voted in a presidential election for the first time in 1860. In his journal for November 6, 1860, he wrote: "At Town House, and cast my vote for Lincoln and the Republican candidates generally—the first vote I ever cast for a President and State officers."[106] Alcott was an abolitionist and a friend of the more radical William Lloyd Garrison.[107] He had attended a rally led by Wendell Phillips on behalf of 17-year-old Thomas Sims, a fugitive slave on trial in Boston. Alcott was one of several who attempted to storm the courthouse; when gunshots were heard, he was the only one who stood his ground, though the effort was unsuccessful.[108] He had also stood his ground in a protest against the trial of Anthony Burns. A group had broken down the door of the Boston courthouse but guards beat them back. Alcott stood forward and asked the leader of the group, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, "Why are we not within?" He then walked calmly into the courthouse, was threatened with a gun, and turned back, "but without hastening a step", according to Higginson.[109]

In 1862, Louisa moved to Washington, D.C. to volunteer as a nurse. On January 14, 1863, the Alcotts received a telegram that Louisa was sick; Bronson immediately went to bring her home, briefly meeting Abraham Lincoln while there.[110] Louisa turned her experience into the book Hospital Sketches. Her father wrote of it, "I see nothing in the way of a good appreciation of Louisa's merits as a woman and a writer."[111]

Henry David Thoreau died on May 6, 1862,[112] likely from an illness he caught from Alcott two years earlier.[113] At Emerson's request, Alcott helped arrange Thoreau's funeral, which was held at First Parish Sanctuary in Concord,[114] despite Thoreau having disavowed membership in the church when he was in his early twenties.[115] Emerson wrote a eulogy,[116] and Alcott helped plan the preparations.[112] Only two years later, neighbor Nathaniel Hawthorne died as well. Alcott served as a pallbearer along with Louis Agassiz, James T. Fields, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and others.[117] With Hawthorne's death, Alcott worried that few of the Concord notables remained. He recorded in his journal: "Fair figures one by one are fading from sight."[118] The next year, Lincoln was assassinated, which Alcott called "appalling news".[119]

In 1868, Alcott met with publisher Thomas Niles, an admirer of Hospital Sketches. Alcott asked Niles if he would publish a book of short stories by his daughter; instead, he suggested she write a book about girls. Louisa May was not interested initially but agreed to try.[120] "They want a book of 200 pages or more", Alcott told his daughter.[121] The result was Little Women, published later that year. The book, which fictionalized the Alcott family during the girls' coming-of-age years, recast the father figure as a chaplain, away from home at the front in the Civil War.

Alcott spoke, as opportunity arose, before the "lyceums" then common in various parts of the United States, or addressed groups of hearers as they invited him. These "conversations" as he called them, were more or less informal talks on a great range of topics, spiritual, aesthetic and practical, in which he emphasized the ideas of the school of American Transcendentalists led by Emerson, who was always his supporter and discreet admirer. He often discussed Platonic philosophy, the illumination of the mind and soul by direct communion with Spirit; upon the spiritual and poetic monitions of external nature; and upon the benefit to man of a serene mood and a simple way of life.[122]

Final years

Alcott's published books, all from late in his life, include Tablets (1868), Concord Days (1872), New Connecticut (1881), and Sonnets and Canzonets (1882). Louisa May attended to her father's needs in his final years. She purchased a house for her sister Anna which had been the last home of Henry David Thoreau, now known as the Thoreau-Alcott House.[123] Louisa and her parents moved in with Anna as well.[124]

After the death of his wife Abby May on November 25, 1877, Alcott never returned to Orchard House, too heartbroken to live there. He and Louisa May collaborated on a memoir and went over her papers, letters, and journals. "My heart bleeds with the memories of those days", he wrote, "and even long years, of cheerless anxiety and hopeless dependence."[125] Louisa noted her father had become "restless with his anchor gone".[126] They gave up on the memoir project and Louisa burned many of her mother's papers.[127]

On January 19, 1879, Alcott and Franklin Benjamin Sanborn wrote a prospectus for a new school which they distributed to potentially interested people throughout the country.[128] The result was the Concord School of Philosophy and Literature, which held its first session in 1879 in Alcott's study in the Orchard House. In 1880 the school moved to the Hillside Chapel, a building next to the house, where he held conversations and, over the course of successive summers, as he entered his eighties, invited others to give lectures on themes in philosophy, religion and letters.[129] The school, considered one of the first formal adult education centers in America, was also attended by foreign scholars. It continued for nine years.

In April 1882, Alcott's friend and benefactor Ralph Waldo Emerson was sick and bedridden. After visiting him, Alcott wrote, "Concord will be shorn of its human splendor when he withdraws behind the cloud." Emerson died the next day.[130] Alcott himself moved out of Concord for his final years, settling at 10 Louisburg Square in Boston beginning in 1885.[131]

As he was bedridden at the end of his life, Alcott's daughter Louisa May came to visit him at Louisburg on March 1, 1888. He said to her, "I am going up. Come with me." She responded, "I wish I could."[132] He died three days later on March 4; Louisa May died only two days after her father.

Beliefs

Alcott was fundamentally and philosophically opposed to corporal punishment as a means of disciplining his students. Instead, beginning at the Temple School, he would appoint a daily student superintendent. When that student observed an infraction, he or she reported it to the rest of the class and, as a whole, they deliberated on punishment.[133] At times, Alcott offered his own hand for an offending student to strike, saying that any failing was the teacher's responsibility. The shame and guilt this method induced, he believed, was far superior to the fear instilled by corporal punishment; when he used physical "correction" he required that the students be unanimously in support of its application, even including the student to be punished.

The most detailed discussion of his theories on education is in an essay, "Observations on the Principles and Methods of Infant Instruction". Alcott believed that early education must draw out "unpremeditated thoughts and feelings of the child" and emphasized that infancy should primarily focus on enjoyment.[134] He noted that learning was not about the acquisition of facts but the development of a reflective state of mind.[135]

Alcott's ideas as an educator were controversial. Writer Harriet Martineau, for example, wrote dubiously that, "the master presupposes his little pupils possessed of all truth; and that his business is to bring it out into expression".[136] Even so, his ideas helped to found one of the first adult education centers in America, and provided the foundation for future generations of liberal education. Many of Alcott's educational principles are still used in classrooms today, including "teach by encouragement", art education, music education, acting exercises, learning through experience, risk-taking in the classroom, tolerance in schools, physical education/recess, and early childhood education. The teachings of William Ellery Channing a few years earlier had also laid the groundwork for the work of most of the Concord Transcendentalists.[137]

The Concord School of Philosophy, which closed following Alcott's death in 1888, was reopened almost 90 years later in the 1970s. It has continued functioning with a Summer Conversational Series in its original building at Orchard House, now run by the Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association.

While many of Alcott's ideas continue to be perceived as being on the liberal/radical edge, they are still common themes in society, including vegetarian/veganism, sustainable living, and temperance/self-control. Alcott described his sustenance as a "Pythagorean diet": Meat, eggs, butter, cheese, and milk were excluded and drinking was confined to well water.[138] Alcott believed that diet held the key to human perfection and connected physical well-being to mental improvement. He further viewed a perfection of nature to the spirit and, in a sense, predicted modern environmentalism by condemning pollution and encouraging humankind's role in sustaining ecology.[139]

Criticism

Alcott's philosophical teachings have been criticized as inconsistent, hazy or abrupt. He formulated no system of philosophy, and shows the influence of Plato, German mysticism, and Immanuel Kant as filtered through the writings of Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[140] Margaret Fuller referred to Alcott as "a philosopher of the balmy times of ancient Greece—a man whom the worldlings of Boston hold in as much horror as the worldlings of Athens held Socrates."[141] In his later years, Alcott related a story from his boyhood: during a total solar eclipse, he threw rocks at the sky until he fell and dislocated his shoulder. He reflected that the event was a prophecy that he would be "tilting at the sun and always catching the fall".[142]

Like Emerson, Alcott was always optimistic, idealistic, and individualistic in thinking. Writer James Russell Lowell referred to Alcott in his poem "Studies for Two Heads" as "an angel with clipped wings".[104] Even so, Emerson noted that Alcott's brilliant conversational ability did not translate into good writing. "When he sits down to write," Emerson wrote, "all his genius leaves him; he gives you the shells and throws away the kernel of his thought."[60] His "Orphic Sayings", published in The Dial, became famous for their hilarity as dense, pretentious, and meaningless. In New York, for example, The Knickerbocker published a parody titled "Gastric Sayings" in November 1840. A writer for the Boston Post referred to Alcott's "Orphic Sayings" as "a train of fifteen railroad cars with one passenger".[61]

Modern critics[who?] often fault Alcott for not being able to financially support his family. Alcott himself worried about his own prospects as a young man, once writing to his mother that he was "still at my old trade—hoping."[143] Alcott held his principles above his and his family's well-being. Shortly before his marriage, for example, his future father-in-law Colonel Joseph May helped him find a job teaching at a school in Boston run by the Society of Free Enquirers, followers of Robert Owen, for a lucrative $1,000 to $1,200 annual salary. He refused it because he did not agree with their beliefs, writing, "I shall have nothing to do with them."[144]

From the other perspective, the Alcotts created an environment which produced two famous daughters in different fields in a time when women were not commonly encouraged to have independent careers.

Works

- Observations on the Principles and Methods of Infant Instruction (1830)

- The Doctrine and Discipline of Human Culture (1836)

- Conversations with Children on the Gospels (Volume I, 1836)

- Conversations with Children on the Gospels (Volume II, 1837)

- Tablets (1868)

- Concord Days (1872)

- Table-Talk (1877)

- New Connecticut: An Autobiographical Poem (1887; first edition privately printed in 1882)

- Sonnets and Canzonets (1882)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, Philosopher and Seer: An Estimate of His Character and Genius in Prose and Verse (1882)

- The Journals of Bronson Alcott (1966)

References

Notes

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 13

- ^ Bedell 1980, pp. 7–9

- ^ Bedell 1980, pp. 9–10

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, p. 19

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 12

- ^ a b Hankins 2004, p. 129

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, pp. 19–21

- ^ Matteson 2007, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b Reisen 2009, p. 9

- ^ Shepard 1937, p. 9

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 15

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 25

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, p. 328

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 16

- ^ a b Bedell 1980, p. 17

- ^ a b Reisen 2009, p. 10

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 18

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, p. 50

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 32

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 34

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, p. 55

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 12

- ^ Bedell 1980, pp. 50–51

- ^ a b c Reisen 2009, p. 13

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 51

- ^ Perry, Lewis. Radical Abolitionism: Anarchy and the Government of God in Antislavery Thought. University of Tennessee Press, 1995: 81.

- ^ Bearse 1880, p. 3.

- ^ a b Matteson 2007, p. 42

- ^ Gura 2007, p. 85

- ^ a b Matteson 2007, p. 43

- ^ Reisen 2009, pp. 14–15

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 48

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 48

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 5

- ^ a b Matteson 2007, p. 50

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 63

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 16

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 53

- ^ a b Packer 2007, p. 55

- ^ a b Dahlstrand 1982, p. 110

- ^ a b Gura 2007, p. 88

- ^ a b Johnson 1906, p. 68

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 122

- ^ Russell, William; Woodbridge, William Channing; Alcott, Amos Bronson (January 1, 1828). American Journal of Education. Wait, Green, and Company.

- ^ Matteson 2007, pp. 66–67

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 33

- ^ LaPlante, Eve (2012). Marmee & Louisa. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-4516-2066-5.

- ^ Schreiner 2006, pp. 49–50

- ^ Packer 2007, p. 59

- ^ a b Gura 2007, p. 89

- ^ Bedell 1980, pp. 130–131

- ^ Baker 1996, p. 184

- ^ Packer 2007, p. 97

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, p. 143

- ^ Buell, Lawrence. Emerson. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003: 32–33. ISBN 0-674-01139-2

- ^ a b Gura 2007, p. 5

- ^ Hankins 2004, p. 24

- ^ a b Packer 2007, p. 115

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 83

- ^ a b Reisen 2009, p. 35

- ^ a b Packer 2007, p. 116

- ^ Felton 2006, p. 23

- ^ a b Schreiner 2006, p. 95

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 99

- ^ Packer 2007, pp. 147–148

- ^ Schreiner 2006, pp. 103–104

- ^ Schreiner 2006, pp. 110–111

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, p. 194

- ^ Packer 2007, pp. 187–188

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 67

- ^ a b c d e Packer 2007, p. 148

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 240

- ^ Francis 2010, pp. 57–58

- ^ Hankins 2004, p. 36

- ^ Gura 2007, p. 176

- ^ a b Felton 2006, p. 132

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 77

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 56

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 179

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 224

- ^ Delano, Sterling F. Brook Farm: The Dark Side of Utopia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004: 118. ISBN 0-674-01160-0

- ^ Baker 1996, p. 221

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 225

- ^ Felton 2006, p. 122

- ^ Reisen 2009, pp. 76–77

- ^ Packer 2007, p. 149

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 230

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 161

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 241

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 228

- ^ Packer 2007, pp. 148–149

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene and Carruth, Gorton. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 62. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 174

- ^ a b Bedell 1980, p. 234

- ^ Bedell 1980, pp. 238–239

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 98

- ^ Matteson 2007, pp. 175–176

- ^ Reisen 2009, pp. 91–92

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 91

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 176

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982, pp. 210–211

- ^ Schreiner 2006, pp. 150–151

- ^ Gura 2007, p. 135

- ^ a b Bedell 1980, p. 319

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 201

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 209

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 61

- ^ Reisen 2009, pp. 163–164

- ^ Packer 2007, p. 226

- ^ Matteson 2007, pp. 281–283

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 219

- ^ a b Schreiner 2006, p. 216

- ^ Packer 2007, p. 271

- ^ Patricia Hohl (April 23, 2012). "Remembering Henry David Thoreau". Thoreau Farm Trust. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Schreiner 2006, pp. 91–92

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1862). "Thoreau". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 10, no. 58. Ticknor and Fields. pp. 239–249. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 186

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 223

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 222

- ^ Madison, Charles A. Irving to Irving: Author-Publisher Relations 1800–1974. New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1974: 36. ISBN 0-8352-0772-2.

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 213

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Richardson, Charles F. (1911). "Alcott, Amos Bronson". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). . Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 528.

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 45. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- ^ Reisen 2009, pp. 262–263

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 387

- ^ Reisen 2009, p. 264

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 388

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 391

- ^ Richardson 1911, p. 529.

- ^ Schreiner 2006, pp. 234–235

- ^ Wilson, Susan. The Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Beverly, Massachusetts: Commonwealth Editions, 2005: 57. ISBN 1-889833-67-3

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 423

- ^ Gura 2007, p. 87

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 53

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 58

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 59

- ^ Richardson 1911, p. 528.

- ^ Baker 1996, p. 217

- ^ Francis 2010, p. 280

- ^ Dahlstrand 1982.

- ^ Nelson, Randy F. (editor). The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981: 152. ISBN 0-86576-008-X

- ^ Matteson 2007, p. 15

- ^ Schreiner 2006, p. 51

- ^ Bedell 1980, p. 49

Sources

- Baker, Carlos (1996). Emerson Among the Eccentrics: A Group Portrait. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-86675-X.

- Bearse, Austin (1880). Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston. Boston: Warren Richardson.

- Bedell, Madelon (1980). The Alcotts: Biography of a Family. New York: Clarkson N. Potter. ISBN 0-517-54031-2.

- Dahlstrand, Federick (1982). Amos Bronson Alcott: An Intellectual Biography. Rutherford: Farleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-838-63016-2.

- Felton, Todd (2006). A Journey into the Transcendentalists' New England. Berkeley: Roaring Forties Press. ISBN 0-9766706-4-X.

- Francis, Richard (2010). Fruitlands: The Alcott Family and Their Search for Utopia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14041-5.

- Gura, Philip F. (2007). American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-3477-2.

- Hankins, Barry (2004). The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31848-4.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Alcott, Amos Bronson". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. pp. 67–68.

- LaPlante, Eve (2012). Marmee & Louisa: The Untold Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Mother. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-2066-5.

- Matteson, John (2007). Eden's Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33359-6.

- Packer, Barbara L. (2007). The Transcendentalists. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2958-1.

- Reisen, Harriet (2009). Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-8299-9.

- Schreiner, Samuel A. Jr. (2006). The Concord Quartet: Alcott, Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, and the Friendship That Freed the American Mind. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-64663-1.

- Shepard, Odell (1937). Pedlar's Progress: The Life of Bronson Alcott. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC 370981.

External links

- Works by Amos Bronson Alcott at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Amos Bronson Alcott at the Internet Archive

- Amos Bronson Alcott Network

- Alcott biography on American Transcendentalism Web

- Alcott at Perspectives in American Literature

- Bronson Alcott: A glimpse at our vegetarian heritage, by Karen Iacobbo

- Guide to Books from the library of Amos Bronson Alcott at Houghton Library, Harvard University

- Guide to Amos Bronson Alcott papers at Houghton Library, Harvard University

- 1799 births

- 1888 deaths

- 19th-century American educators

- 19th-century American philosophers

- Abolitionists from Boston

- Alcott family

- American male feminists

- American people of English descent

- American tax resisters

- American veganism activists

- American women's rights activists

- Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery (Concord, Massachusetts)

- Founders of utopian communities

- Massachusetts Republicans

- Members of the Transcendental Club

- Opponents of tea drinking

- People from Concord, Massachusetts

- People from Harvard, Massachusetts

- People from Wolcott, Connecticut

- Philosophers from Connecticut

- Philosophers from Massachusetts

- Scholars of feminist philosophy

- Schoolteachers from Massachusetts

- Sonneteers

- Underground Railroad people

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !