Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea[1] is a sea of the North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba to Puerto Rico, the Lesser Antilles to the east from the Virgin Islands to Trinidad and Tobago, South America to the south from the Venezuelan coastline to the Colombian coastline, and Central America and the Yucatán Peninsula to the west from Panama to Mexico. The geopolitical region centered around the Caribbean Sea, including the numerous islands of the West Indies and adjacent coastal areas in the mainland of the Americas, is known as the Caribbean.

The Caribbean Sea is one of the largest seas on Earth and has an area of about 2,754,000 km2 (1,063,000 sq mi).[2][3] The sea's deepest point is the Cayman Trough, between the Cayman Islands and Jamaica, at 7,686 m (25,217 ft) below sea level. The Caribbean coastline has many gulfs and bays: the Gulf of Gonâve, the Gulf of Venezuela, the Gulf of Darién, Golfo de los Mosquitos, the Gulf of Paria and the Gulf of Honduras.

The Caribbean Sea has the world's second-largest barrier reef, the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef. It runs 1,000 km (620 mi) along the Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras[4] coasts.

History

The name Caribbean derives from the Caribs, one of the region's dominant native people at the time of European contact during the late 15th century. After Christopher Columbus landed in The Bahamas in 1492 and later discovered some of the islands in The Caribbean, the Spanish term Antillas applied to the lands; stemming from this, the Sea of the Antilles became a common alternative name for the "Caribbean Sea" in various European languages. Spanish dominance in the region remained undisputed during the first century of European colonization.

From the 16th century, Europeans visiting the Caribbean region distinguished the "South Sea" (the Pacific Ocean south of the isthmus of Panama) from the "North Sea" (the Caribbean Sea north of the same isthmus).[5]

The Caribbean Sea had been unknown to the populations of Eurasia until after 1492 when Christopher Columbus sailed into Caribbean waters to find a sea route to Asia. At that time, the Americas were generally unknown to most Europeans, although they had been visited in the 10th century by the Vikings. Following Columbus's discovery of the islands, the area was quickly colonized by several Western cultures (initially Spain, then later England, the Dutch Republic, France, Courland and Denmark). Following the colonization of the Caribbean islands, the Caribbean Sea became a busy area for European-based marine trading and transports. This commerce eventually attracted pirates such as Samuel Bellamy and Blackbeard.

As of 2015[update] the area is home to 22 island territories and borders 12 continental countries.[citation needed]

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Caribbean Sea as follows:[6]

- On the North. In the Windward Channel – a line joining Caleta Point (74°15′W) in Cuba and Pearl Point (19°40′N) in Haiti. In the Mona Passage – a line joining Cape Engaño and the extreme of Agujereada (18°31′N 67°08′W / 18.517°N 67.133°W) in Puerto Rico.

- Eastern limits. From Point San Diego (Puerto Rico) Northward along the meridian thereof (65°39′W) to the 100-fathom line, thence Eastward and Southward, in such a manner that all islands, shoals and narrow waters of the Lesser Antilles are included in the Caribbean Sea as far as but not including Trinidad. From before Trinidad to Baja Point (9°32′N 61°0′W / 9.533°N 61.000°W) in Venezuela.

Although Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados are on the same continental shelf, they are considered to be in the Atlantic Ocean rather than in the Caribbean Sea.[7]

Geology

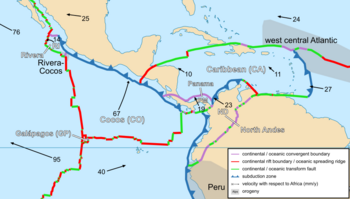

The Caribbean Sea is an oceanic sea on the Caribbean Plate. The Caribbean Sea is separated from the ocean by several island arcs of various ages. The youngest stretches from the Lesser Antilles to the Virgin Islands to north of Trinidad and Tobago, which is in the Atlantic. This arc was formed by the collision of the South American Plate with the Caribbean Plate. It included active and extinct volcanoes such as Mount Pelee, the Quill on Sint Eustatius in the Caribbean Netherlands, La Soufrière in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Morne Trois Pitons on Dominica. The larger islands in the northern part of the sea Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica and Puerto Rico lie on an older island arc.

The geological age of the Caribbean Sea is estimated to be between 160 and 180 million years and was formed by a horizontal fracture that split the supercontinent called Pangea in the Mesozoic Era.[10] It is assumed the proto-caribbean basin existed in the Devonian period and in the early Carboniferous movement of Gondwana to the north and its convergence with the Euramerica basin decreased in size. The next stage of the Caribbean Sea's formation began in the Triassic. Powerful rifting led to the formation of narrow troughs, stretching from modern Newfoundland to the Gulf of Mexico's west coast, forming siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. In the early Jurassic due to powerful marine transgression, water broke into the present area of the Gulf of Mexico creating a vast shallow pool. Deep basins emerged in the Caribbean during the Middle Jurassic rifting. The emergence of these basins marked the beginning of the Atlantic Ocean and contributed to the destruction of Pangaea at the end of the late Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the Caribbean acquired a shape close to today. In the early Paleogene due to marine regression the Caribbean became separated from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean by the land of Cuba and Haiti. The Caribbean remained like this for most of the Cenozoic until the Holocene when rising water levels of the oceans restored communication with the Atlantic Ocean.

The Caribbean's floor is composed of sub-oceanic sediments of deep red clay in the deep basins and troughs. On continental slopes and ridges calcareous silts are found. Clay minerals have likely been deposited by the mainland river Orinoco and the Magdalena River. Deposits on the bottom of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico have a thickness of about 1 km (0.62 mi). Upper sedimentary layers relate to the period from the Mesozoic to the Cenozoic (250 million years ago) and the lower layers from the Paleozoic to the Mesozoic.

The Caribbean seafloor is divided into five basins separated from each other by underwater ridges and mountain ranges. Atlantic Ocean water enters the Caribbean through the Anegada Passage between the Lesser Antilles and the Virgin Islands and the Windward Passage between Cuba and Haiti. The Yucatán Channel between Mexico and Cuba links the Gulf of Mexico with the Caribbean. The deepest points of the sea lie in Cayman Trough with depths reaching approximately 7,686 m (25,220 ft). Despite this, the Caribbean Sea is considered a relatively shallow sea compared to other bodies of water. The pressure of the South American Plate to the east of the Caribbean causes the region of the Lesser Antilles to have high volcanic activity. A very serious eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902 caused many casualties.

The Caribbean sea floor is also home to two oceanic trenches: the Cayman Trench and the Puerto Rico Trench, which put the area at a high risk of earthquakes. Underwater earthquakes pose a threat of generating tsunamis which could have a devastating effect on the Caribbean islands. Scientific data reveals that over the last 500 years, the area has seen a dozen earthquakes above 7.5 magnitude.[11] Most recently, a 7.1 earthquake struck Haiti on January 12, 2010.

Oceanography

The hydrology of the sea has a high level of homogeneity. Annual variations in monthly average water temperatures at the surface do not exceed 3 °C (5.4 °F). Over the past 50 years, the Caribbean has gone through three stages: cooling until 1974, a cold phase with peaks during 1974–1976 and 1984–1986, and finally a warming phase with an increase in temperature of 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) per year. Virtually all temperature extremes were associated with the phenomena of El Niño and La Niña. The salinity of the seawater is about 3.6%, and its density is 1,023.5–1,024.0 kg/m3 (63.90–63.93 lb/cu ft). The surface water color is blue-green to green.

The Caribbean's depth in its wider basins and deep-water temperatures are similar to those of the Atlantic. Atlantic deep water is thought to spill into the Caribbean and contribute to the general deep water of its sea.[12] The surface water (30 m; 100 ft) acts as an extension of the northern Atlantic as the Guiana Current and part of the North Equatorial Current enter the sea on the east. On the western side of the sea, the trade winds influence a northerly current which causes an upwelling and a rich fishery near Yucatán.[13]

Ecology

The Caribbean is home to about 9% of the world's coral reefs, covering about 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi), most of which are located off the Caribbean Islands and the Central American coast.[14] Among them, the Belize Barrier Reef stands out, with an area of 963 km2 (372 sq mi), which was declared a World Heritage Site in 1996. It forms part of the Great Mayan Reef (also known as the MBRS) and, being over 1,000 km (600 mi) in length, is the world's second longest. It runs along the Caribbean coasts of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras.

Since 2005 unusually warm Caribbean waters have been increasingly threatening the coral reefs. Coral reefs support some of the most diverse marine habitats in the world, but they are fragile ecosystems. When tropical waters become unusually warm for extended periods of time, microscopic plants called zooxanthellae, which are symbiotic partners living within the coral polyp tissues, die off. These plants provide food for the corals and give them their color. The result of the death and dispersal of these tiny plants is called coral bleaching, and can lead to the devastation of large areas of reef. Over 42% of corals are completely bleached, and 95% are experiencing some type of whitening.[15] Historically the Caribbean is thought to contain 14% of the world's coral reefs.[16]

The habitats supported by the reefs are critical to such tourist activities as fishing and scuba diving, and provide an annual economic value to Caribbean nations of US$3.1–4.6 billion. Continued destruction of the reefs could severely damage the region's economy.[17] A Protocol of the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region came in effect in 1986 to protect the various endangered marine life of the Caribbean through forbidding human activities that would advance the continued destruction of such marine life in various areas. Currently this protocol has been ratified by 15 countries.[18] Also, several charitable organisations have been formed to preserve the Caribbean marine life, such as Sea Turtle Conservancy which seeks to study and protect sea turtles while educating others about them.[19]

In connection with the foregoing, the Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, conducted a regional study, funded by the Department of Technical Cooperation of the International Atomic Energy Agency, in which specialists from 11 Latin American countries (Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Dominican Republic, Venezuela) plus Jamaica participated. The findings indicate that heavy metals such as mercury, arsenic, and lead, have been identified in the coastal zone of the Caribbean Sea. Analysis of toxic metals and hydrocarbons is based on the investigation of coastal sediments that have accumulated less than 50 meters deep during the last hundred and fifty years. The project results were presented in Vienna in the forum "Water Matters", and the 2011 General Conference of that multilateral organization.[20]

After the Mediterranean, the Caribbean Sea is the second most polluted sea. Pollution (in the form of up to 300,000 tonnes of solid garbage dumped into the Caribbean Sea each year) is progressively endangering marine ecosystems, wiping out species, and harming the livelihoods of the local people, which is primarily reliant on tourism and fishing.[21][22][23][24]

KfW took part in a €25.7 million funding agreement to eliminate marine trash and boost the circular economy in the Caribbean's Small Island Developing States. The project "Sustainable finance methods for marine preservation in the Caribbean" will assist remove solid waste and keep it out of the marine and coastal environment by establishing a new facility under the Caribbean Biodiversity Fund (CBF).[21] Non-governmental organizations, universities, public institutions, civil society organizations, and the corporate sector are all eligible for financing. The project is estimated to prevent and remove at least 15 000 tonnes of marine trash, benefiting at least 20 000 individuals.[21]

Climate

The climate of the Caribbean is driven by the low latitude and tropical ocean currents that run through it. The principal ocean current is the North Equatorial Current, which enters the region from the tropical Atlantic. The climate of the area is tropical, varying from tropical rainforest in some areas to tropical savanna in others. There are also some locations that are arid climates with considerable drought in some years.

Rainfall varies with elevation, size, and water currents (cool upwelling keep the ABC islands arid). Warm, moist trade winds blow consistently from the east, creating both rainforest and semi-arid climates across the region. The tropical rainforest climates include lowland areas near the Caribbean Sea from Costa Rica north to Belize, as well as the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, while the more seasonal dry tropical savanna climates are found in Cuba, northern Venezuela, and southern Yucatán, Mexico. Arid climates are found along the extreme northern coast of Venezuela out to the islands including Aruba and Curaçao, as well as the northern tip of Yucatán[26]

Tropical cyclones are a threat to the nations that rim the Caribbean Sea. While landfalls are infrequent, the resulting loss of life and property damage makes them a significant hazard to life in the Caribbean. Tropical cyclones that impact the Caribbean often develop off the West coast of Africa and make their way west across the Atlantic Ocean toward the Caribbean, while other storms develop in the Caribbean itself. The Caribbean hurricane season as a whole lasts from June through November, with the majority of hurricanes occurring during August and September. On average around nine tropical storms form each year, with five reaching hurricane strength. According to the National Hurricane Center 385 hurricanes occurred in the Caribbean between 1494 and 1900.

Flora and fauna

The region has a high level of biodiversity and many species are endemic to the Caribbean.

Vegetation

The vegetation of the region is mostly tropical but differences in topography, soil and climatic conditions increase species diversity. Where there are porous limestone terraced islands these are generally poor in nutrients. It is estimated that 13,000 species of plants grow in the Caribbean of which 6,500 are endemic. For example, guaiac wood (Guaiacum officinale), the flower of which is the national flower of Jamaica and the Bayahibe rose (Pereskia quisqueyana) which is the national flower of the Dominican Republic and the ceiba which is the national tree of both Puerto Rico and Guatemala. The mahogany is the national tree of the Dominican Republic and Belize. The caimito (Chrysophyllum cainito) grows throughout the Caribbean. In coastal zones there are coconut palms and in lagoons and estuaries are found thick areas of black mangrove and red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle).

In shallow water flora and fauna is concentrated around coral reefs where there is little variation in water temperature, purity and salinity. Leeward sides of lagoons provide areas of growth for sea grasses. Turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum) is common in the Caribbean as is manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme) which can grow together as well as in fields of single species at depths up to 20 m (66 ft). Another type shoal grass (Halodule wrightii) grows on sand and mud surfaces at depths of up to 5 m (16 ft). In brackish water of harbours and estuaries at depths less than 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) widgeongrass (Ruppia maritima) grows. Representatives of three species belonging to the genus Halophila, (Halophila baillonii, Halophila engelmannii and Halophila decipiens) are found at depths of up to 30 m (98 ft) except for Halophila engelmani which does not grow below 5 m (16 ft) and is confined to the Bahamas, Florida, the Greater Antilles and the western part of the Caribbean. Halophila baillonii has been found only in the Lesser Antilles.[27]

Fauna

Marine biota in the region have representatives of both the Indian and Pacific oceans which were caught in the Caribbean before the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama four million years ago.[28] In the Caribbean Sea there are around 1,000 documented species of fish, including sharks (bull shark, tiger shark, silky shark and Caribbean reef shark), flying fish, giant oceanic manta ray, angel fish, spotfin butterflyfish, parrotfish, Atlantic Goliath grouper, tarpon and moray eels. Throughout the Caribbean there is industrial catching of lobster and sardines (off the coast of Yucatán Peninsula).

There are 90 species of mammals in the Caribbean including sperm whales, humpback whales and dolphins. The island of Jamaica is home to seals and manatees. The Caribbean monk seal which lived in the Caribbean is considered extinct. Solenodons and hutias are mammals found only in the Caribbean; only one extant species is not endangered.

There are 500 species of reptiles (94% of which are endemic). Islands are inhabited by some endemic species such as rock iguanas and American crocodile. The blue iguana, endemic to the island of Grand Cayman, is endangered. The green iguana is invasive to Grand Cayman. The Mona ground iguana which inhabits the island of Mona, Puerto Rico, is endangered. The rhinoceros iguana from the island of Hispaniola which is shared between Haiti and the Dominican Republic is also endangered. The region has several types of sea turtle (loggerhead, green turtle, hawksbill, leatherback turtle, Atlantic ridley and olive ridley). Some species are threatened with extinction.[29] Their populations have been greatly reduced since the 17th century – the number of green turtles has declined from 91 million to 300,000 and hawksbill turtles from 11 million to less than 30,000 by 2006.[30]

All 170 of the amphibian species that live in the region are endemic. The habitats of almost all members of the toad family, poison dart frogs, tree frogs and leptodactylidae (a type of frog) are limited to only one island.[31] The golden coqui is in serious threat of extinction.

In the Caribbean, 600 species of birds have been recorded, of which 163 are endemic such as todies, Fernandina's flicker and palmchat. The American yellow warbler is found in many areas, as is the green heron. Of the endemic species 48 are threatened with extinction including the Puerto Rican amazon, and the Zapata wren. According to BirdLife International in 2006 in Cuba 29 species of bird were in danger of extinction and two species officially extinct.[32] The black-fronted piping guan is endangered. The Antilles along with Central America lie in the flight path of migrating birds from North America so the size of populations is subject to seasonal fluctuations. Parrots and bananaquits are found in forests. Over the open sea can be seen frigatebirds and tropicbirds.

Economy and human activity

The Caribbean region has seen a significant increase in human activity since the colonization period. The sea is one of the largest oil production areas in the world, producing approximately 170 million tons[clarification needed] per year.[33] The area also generates a large fishing industry for the surrounding countries, accounting for 500,000 tonnes (490,000 long tons; 550,000 short tons) of fish a year.[34]

Human activity in the area also accounts for a significant amount of pollution. The Pan American Health Organization estimated in 1993 that only about 10% of the sewage from the Central American and Caribbean Island countries is properly treated before being released into the sea.[33]

The region has been famous for its rum production - the drink is first mentioned in records from Barbados in around 1650, although it was likely to have been produced beforehand across the other islands.[35]

The Caribbean region supports a large tourism industry. The Caribbean Tourism Organization calculates that about 12 million people a year visit the area, including (in 1991–1992) about 8 million cruise ship tourists. Tourism based upon scuba diving and snorkeling on coral reefs of many Caribbean islands makes a major contribution to their economies.[36]

Gallery

-

Sunrise over the south beach of Jamaica

-

Beach of Curaçao

-

Palm Beach, Aruba

-

Cayo Coco, Cuba

-

Sunset in the Caribbean Sea

See also

- Greater Antilles

- Hispanic America

- Ibero-America

- Intra-Americas Sea

- Kick 'em Jenny

- Latin America

- Lesser Antilles

- List of Caribbean islands

- List of Caribbean Countries

- List of Caribbean countries by population

- Piracy in the Caribbean

- Territorial evolution of the Caribbean

- West Indies

References

- ^ (Spanish: Mar Caribe; French: Mer des Caraïbes; Haitian Creole: Lanmè Karayib; Jamaican Patois: Kiaribiyan Sii; Dutch: Caraïbische Zee; Papiamento: Laman Karibe)

- ^ The Caribbean Sea Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine All The Sea. URL last accessed May 7, 2006

- ^ "The Caribbean Sea". Archived from the original on 2018-04-21. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ^ "Mesoamerican Reef | Places". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 2020-11-13. Retrieved 2016-10-21.

- ^

Gorgas, William C. (1912). "Sanitation at Panama". Journal of the American Medical Association. 58 (13). American Medical Association: 907. doi:10.1001/jama.1912.04260030305001. ISSN 0002-9955.

The Pacific Ocean, south of this isthmus [Panama], was known to the early explorers as the South Sea, and the Caribbean, lying to the north, as the North Sea.

- ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Stefanov, William (16 December 2009). "Greater Bridgetown Area, Barbados". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ National Geophysical Data Center, 1999. Global Land One-kilometer Base Elevation (GLOBE) v.1. Hastings, D. and P.K. Dunbar. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA Archived 2011-02-10 at the Wayback Machine. doi:10.7289/V52R3PMS [access date: 2015-03-16]

- ^ Amante, C. and B.W. Eakins, 2009. ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis. NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. doi:10.7289/V5C8276M [access date: 2015-03-18].

- ^ Iturralde-Vinent, Manuel (2004), The first inhabitants of the Caribbean, Cuban Science Network. URL accessed on 28/07/2007

- ^ Dawicki, Shelley. "Tsunamis in the Caribbean? It's possible". Oceanus. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2006.

- ^ Pernetta, John. (2004). Guide to the Oceans. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books, Inc. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-55297-942-6.

- ^ Pernetta, John. (2004). Guide to the Oceans. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books, Inc. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-1-55297-942-6.

- ^ Status of coral reefs in the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean Archived June 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine World Resource Institute. URL accessed on April 29, 2006.

- ^ [1] Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine Inter Press Service News Agency – Mesoamerican Coral Reef on the way to becoming a Marine Desert

- ^ Elder, Danny and Pernetta, John. (1991). The Random House Atlas of the Oceans. New York : Random House. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-679-40830-7.

- ^ Alarm sounded for Caribbean coral Archived 2011-08-12 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. URL accessed on April 29, 2006.

- ^ Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife to the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region (SPAW) Archived 2018-04-05 at the Wayback Machine NOAA Fisheries: Office of Protected Resources. URL accessed on April 30, 2006.

- ^ Caribbean Conservation Corporation Archived October 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Orion Online. URL last accessed May 1, 2006.

- ^ Analysis of Contaminants in the Caribbean Sea over the last 150 years Archived 2017-05-17 at the Wayback Machine. National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) 2012 (Spa).

- ^ a b c "The Clean Oceans Initiative". European Investment Bank. 2023-02-23. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ "Pollution in the Mediterranean". UNEPMAP. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ "Over 200,000 tonnes of plastic leaking into the Mediterranean each year – IUCN report". IUCN. 2020-10-27. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ "Marine Pollution Threatens the Caribbean Sea". World Bank. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ "NASA – NASA Satellites Record a Month for the Hurricane History Books". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- ^ Silverstein, Alvin (1998) Weather And Climate (Science Concepts); page 17. 21st Century. ISBN 978-0-7613-3223-7

- ^ Caribbean seagrass. Seagrass watch, retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ Robert James Menzies, John C Ogden. "Caribbean Sea" Archived 2011-08-04 at the Wayback Machine. Britannica Online Encyclopaedia.

- ^ Severin Carrell, "Caribbean Sea Turtles Close to Extinction", The Independent, 28 November 2004.

- ^ Historic Caribbean Sea Turtle Population falls 99%. Plunge has significant ecological consequences. Mongabay.com (August 1, 2006).

- ^ Conservation International Caribbean Islands Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Threatened Species.

- ^ "Birdlife International" Archived 2020-12-19 at the Wayback Machine – Red List Cuba.

- ^ a b An Overview of Land Based Sources of Marine Pollution Archived 2006-12-07 at the Wayback Machine Caribbean Environment Programme. URL last accessed May 14, 2006.

- ^ LME 12: Caribbean Sea Archived 2006-05-04 at the Wayback Machine NOAA Fisheries Northeast Fisheries Science Center Narragansett Laboratory. URL last accessed May 14, 2006.

- ^ "Rum in the Caribbean". nationalgeographic.com. 12 July 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean: Economic Valuation Methodology Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine World Resources Institute 2009.

Further reading

- Donovan, Stephen K., and Trevor A. Jackson, eds. Caribbean Geology: An Introduction (1994) online

- Gallegos, Artemio. "Descriptive physical oceanography of the Caribbean Sea". Small Islands Marine Science and Sustainable Development 51 (1996): 36–55.

- Glover K., Linda (2004), Defying Ocean's End: An Agenda For Action, Island Press, p. 9. ISBN 978-1-55963-753-4

- Morgan, Philip D. et al. Sea and Land: An Environmental History of the Caribbean (Oxford University Press, 2022) online review

- Peters, Philip Dickenson (2003), Caribbean WOW 2.0, Islandguru Media, p. 100^^75;4. ISBN 978-1-929970-04-9.

- Snyderman, Marty (1996), Guide to Marine Life: Caribbean-Bahamas-Florida, Aqua Quest Publications, pp. 13–14, 19. ISBN 978-1-881652-06-9.

- Wood, Robert E. "Caribbean cruise tourism: Globalization at sea." Annals of tourism research 27.2 (2000): 345–370.

- Woodring, Wendell Phillips. "Caribbean land and sea through the ages." Geological Society of America Bulletin 65.8 (1954): 719–732. GSA Bulletin (1954) 65 (8): 719–732. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1954)65[719:CLASTT2.0.CO]

- Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean: Economic Valuation Methodology, World Resources Institute 2007.

External links

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !