Caroline Harrison

Caroline Harrison | |

|---|---|

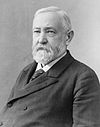

Portrait by C. Parker, 1889 | |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role March 4, 1889 – October 25, 1892 | |

| President | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | Frances Cleveland |

| Succeeded by | Mary Harrison McKee (acting) |

| 1st President General of the Daughters of the American Revolution | |

| In office 1890–1892 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Mary Virginia Ellet Cabell (Vice President presiding) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Caroline Lavinia Scott October 1, 1832 Oxford, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | October 25, 1892 (aged 60) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Crown Hill Cemetery |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, Russell, Mary, Elizabeth |

| Parent |

|

| Education | Miami University (BM) |

| Signature | |

Caroline Lavinia Harrison (née Scott; October 1, 1832 – October 25, 1892) was an American music teacher, artist, and the first lady of the United States from 1889 until her death. She was married to President Benjamin Harrison, and was the second first lady to die while serving in the role.

The daughter of a college professor, Harrison was well-educated, and she expressed interest in art, music, and literature throughout her life. She married Benjamin Harrison in 1853 and taught music while he engaged in a legal and political career. She was heavily involved in the community, working at her church, participating in charity work, and managing local institutions such as an orphanage and a women's club. During the Civil War, she contributed to the war effort through women's volunteer groups. When her husband was nominated for the presidency, she was a hostess as her home became the center of a front porch campaign.

As first lady, Harrison took little interest in her duties as hostess and dedicated much of her time to charity work. She was in favor of women's rights, and she was an organizing member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, serving as its first President General. Harrison engaged in a major undertaking to renovate the White House, having much of its interior and utilities entirely redone. These renovations included the addition of electricity, though the family declined to use it for fear of electrocution. Her plans for the White House would later influence the construction of the East Wing and the West Wing. She also took inventory of furnishings and other possessions kept in the White House, beginning the practice of White House historical preservation.

Early life

Caroline Lavinia Scott was born on October 1, 1832,[1]: 147 in Oxford, Ohio, to Mary Potts Neal, a teacher at a girls' school, and John Witherspoon Scott, a Presbyterian minister and professor at Miami University.[2]: 1 Caroline's parents were abolitionists, and were active in the Underground Railroad.[3] Her great-grandfather was the founder of the first Presbyterian church in the United States, and of the College of New Jersey, which was later renamed Princeton University.[4] She had two sisters and two brothers.[5]: 151 Among her family, she was known as "Carrie".[6]: 83 Her father left Miami University following a dispute over his abolitionist beliefs, and the family moved to Cincinnati.[2]: 2 Her parents were supporters of women's education, and they ensured that she was well educated.[7]

While in Cincinnati, Caroline attended a girls' school that her father founded.[8]: 187 Caroline's father also took a job teaching science and mathematics at Farmer's College in Cincinnati. Caroline began a courtship with Benjamin Harrison, one of her father's students at Farmer's College.[7] The extent of their relationship was kept secret,[9]: 96 and the two would often meet for buggy and sleigh rides together. They would also secretly attend dancing parties, which were seen as sinful at her father's institute.[1]: 148 When Caroline's father was appointed the first president of the Oxford Female Institute, the Scotts returned to Oxford, and Benjamin transferred to Miami University so he could be close to Caroline.[2]: 4

In addition to her enrollment as a student, Scott took a part-time job at the institute teaching art and music.[9]: 96 They were engaged in 1852, but they delayed the marriage until the following year.[8]: 187 While Harrison advanced his legal career, Scott took a job as a music teacher in Carrollton, Kentucky, with Bethania Bishop Bennet.[2]: 5 Bennet had previously been in charge of the Oxford Female Institute.[10] Caroline was severely overworked while in Kentucky, which negatively affected her health: as a result she and Benjamin wed sooner than originally planned.[2]: 5 They were married on October 20, 1853, with Caroline's father presiding.[1]: 148

Benjamin and Caroline were often contrasted with one another, as Benjamin's serious personality was distinct from Caroline's friendly demeanor.[5]: 152 After their marriage, they stayed at the Harrison family home in North Bend, Ohio until Benjamin was admitted to the bar 1854, at which point they moved to Indianapolis.[1]: 148 The Harrisons struggled financially in the early years of their marriage; though the Harrison family had been well-to-do, their wealth had been diluted over generations. Caroline kept house while Benjamin worked as an attorney.[6]: 83–84 While she was pregnant with her first child in 1854, Caroline stayed at her family home in Ohio. The Harrisons' lives were further complicated by a fire that destroyed their home in Indianapolis the same year.[8]: 188

The Harrisons had three children, two of whom survived to adulthood. Russell Benjamin Harrison was born on August 12, 1854; Mary Scott Harrison was born on April 3, 1858; and another daughter died at birth in 1861. The family lived more comfortably as Benjamin's legal career advanced.[1]: 148–149 In addition to keeping house, Caroline took up several hobbies. She began china painting and playing the piano and the organ.[6]: 85 Harrison also established an art studio from which she taught ceramics and other forms of art.[9]: 97 The Harrisons were active in the First Presbyterian Church; Caroline participated in the church choir, sewing society, and fundraisers, and she also taught Sunday school. She was also active in the community, joining the Indianapolis Orphans' Asylum board of managers in 1860 and holding the position until her death.[1]: 149 She served as the president of the Indianapolis Woman's Club.[6]: 85–86 Other organizations to which she contributed include the Indianapolis Benevolent Society, a group that distributed aid in the community, and the Home for Friendless Women, a woman's retirement home.[11]

Civil War and senator's wife

Harrison experienced periods of loneliness and depression as her husband began his political career, for he was often away and their marriage was neglected. This was exacerbated by the onset of the Civil War, at which time both Caroline and Benjamin sought to help in the war effort.[5]: 153 Caroline joined volunteer groups such as the Ladies Patriotic Association and the Ladies Sanitary Committee. When visiting her husband at the soldiers' camp, she would mend uniforms and perform other chores, and when at home in Indianapolis, she would tend to wounded soldiers.[1]: 149 She continued her education after the war, taking literature and art classes.[5]: 153–154 Her pursuit of literature led her to establish the Impromptu Club, a local literary discussion group,[8]: 188 while her pursuit of art became such that she began featuring her work in art exhibitions.[5]: 153–154 She also took a position on the board of lady managers of the Garfield Hospital.[1]: 150 Harrison faced several serious health problems in the 1880s: she took a severe fall on the ice, underwent surgery in 1883, and became seriously ill in 1886.[1]: 150 In 1874, the Harrisons oversaw the construction of a sixteen-room house. It was finished in 1875, and gave Caroline experience in planning a home that would prove valuable when she became first lady years later.[12]

Benjamin continued to pursue politics after the war. He ran an unsuccessful campaign to be the Governor of Indiana in 1876, and he was elected to the United States Senate in 1880.[8]: 188 After his election, Caroline oversaw the family's move to a rented suite in Washington, D.C.[13]: 108–109 She served as an advisor in his political career and assisted him in his political campaigns.[5]: 154 Her work as a family hostess grew significantly when her husband was chosen as the Republican candidate for the 1888 presidential election. He ran a front porch campaign as was common at the time, bringing thousands of people through their home. She also became a public figure in her own right, and she was used in the campaign to contrast with the popular incumbent first lady Frances Cleveland. The campaign was stressful for Harrison, and she expressed a hope to find privacy in the White House. Her husband was elected president, and was sworn in on March 4, 1889.[5]: 154 [8]: 188–189

First Lady

Harrison was responsible for a large family in the White House; in addition to the president and herself, the White House was home to their two children and their families, Caroline's father, Caroline's sister Elizabeth, and Elizabeth's widowed daughter. Managing this large family contributed to her image as grandmotherly and as an ideal of domestic life. Both her daughter and her daughter-in-law helped with the responsibilities of the first lady.[1]: 151 She considered her domestic duties to be her primary responsibilities, expressing little interest in her role as White House hostess. Harrison continued in her artistic pursuits while she was first lady, and she would mail ceramic milk sets to parents that named their children after the president.[14]: 273

To appeal to the public, Harrison would arrange publicity photos of her infant grandson, popularly known as "Baby McKee".[15]: 49 She also continued her charitable work as first lady, giving her little time to organize grand receptions. She did implement some reforms for presidential receptions; Harrison abolished the practice of handshaking in receiving lines, and she restored dancing as a common practice.[1]: 151 Harrison caused one major political controversy in 1889 when she accepted a seaside cottage from John Wanamaker as a gift, leading to accusations of bribery.[1]: 152

Harrison supported women's rights movements while serving as first lady. It was on her advice that her husband appointed Alice Sanger to the White House staff, the first woman to hold such a position.[8]: 191 Harrison also organized educational programs in the White House for the wives and daughters of cabinet members, including ceramics and French classes.[9]: 98 In 1890, Harrison was the first President General of the Daughters of the American Revolution, a woman's organization that celebrated the contributions of women during the founding of the United States. Her involvement gave the organization legitimacy, and her first speech to the group was the first public speech to be written and delivered by a first lady.[1]: 152 The same year, she and several other women helped raise funds for the Johns Hopkins University Medical School on the condition that it admit women.[16] This was the first medical school in the United States to accept women, and it would lead to similar policies in other medical schools.[9]: 98

Renovations and preservation

When she became the first lady, Harrison inspected the White House in its entirety and found many problems that she wished to address. The structure had been damaged by rot as well as by pests such as termites and rats. She consulted with Thomas Edison to bring electricity into the building, but he concluded that it could not safely incorporate electrical wiring in its current state. The extended family also found that there were not enough bedrooms between them and that there was only one bathroom.[6]: 86–87 She took particular issue with the integration of the residential spaces and public offices, allowing visitors access to the family's quarters.[8]: 189 She wished to entirely reconstruct the White House, even drawing plans with architect Frederick D. Owen, but Congress was unwilling to fund the project.[1]: 151 Instead, Congress authorized $35,000 (equivalent to $1,055,574 in 2021) for renovations, decoration, and modernization.[17]

Harrison made large changes with the allocated funds. The rooms were repainted, and the drapes, carpets, and upholstery were replaced.[1]: 151 The kitchens, which had not been updated in over forty years, were modernized.[6]: 87 More bathrooms were installed, and new furniture was purchased for the house.[14]: 273 Wooden structures in the state rooms were repainted ivory, and five layers of floorboards were replaced due to rot. She oversaw the installation of electrical wiring over a period of four months, but the family and much of the staff were afraid to use the light switches.[18] She also authorized other utilities, including the installation of a heating system and modernized plumbing.[8]: 190 The wood-frame bathtubs were replaced with iron tubs.[19] To address the rat problem, she released ferrets,[8]: 190 and she had the basement redone with concrete floors and tiled walls.[1]: 151 For decoration, Harrison introduced the use of orchids as the official floral decoration at state receptions,[8]: 191 and she also had the first White House Christmas tree put up.[1]: 151 The Green Room was redone in rococo style.[19] By the time she had finished, she had refurbished the White House in its entirety, becoming the first first lady to do so.[8]: 190

Harrison took interest in the history of the White House, and she would offer personal tours.[1]: 151 She ended the practice of selling off furnishing at the end of a presidential administration to preserve historic pieces from past administrations and mitigate a continual need of refurnishing.[11] She especially took interest in china from previous administrations that had been stored in the attic, organizing it and creating what would become the White House china collection.[14]: 273 She also designed china of her own to be used as the official White House china of her husband's presidency.[18] She had her husband order a total account of the furniture in the White House that documented the history of every item.[1]: 151 One such item, the Resolute desk, was also used by subsequent presidents.[18] Under her management, the White House hired its first art curator, a practice that would be revived by the Kennedy administration.[11]

Illness and death

In 1891, it was discovered that Harrison had tuberculosis.[14]: 275 As her health declined, she delegated her responsibilities to relatives, primarily her daughter Mary. This caused conflict with the second lady and the wife of the Secretary of State, who both felt that they were entitled to the position. She traveled to spend the summer of 1892 in the Adirondack Mountains, as the air was considered healthful for tuberculosis patients. After her condition became terminal, she returned to the White House. Her condition was worsened by suspicions that her husband had begun a romantic relationship with her niece Mary Scott Dimmick.[8]: 192 In respect for her condition, both her husband and his opponent limited their campaign activity in the 1892 presidential election.[5]: 156

Harrison died on October 25, 1892, two weeks before her husband was defeated for reelection.[14]: 275 It is believed that she died from a combination of tuberculosis and another illness, such as typhoid fever or influenza. Preliminary services were held in the East Room, then her body was returned to Indianapolis for the final funeral at her church and her burial at Crown Hill Cemetery. Her duties as first lady were taken over by their daughter Mary for the remainder of the term. In 1896, Benjamin married Mary Scott Dimmick.[8]: 192

Legacy

Harrison is described as an "underrated" first lady who was more active than most first ladies of her generation.[5]: 156 [8]: 186 [11] She is ranked poorly by historians, typically being placed in the bottom quartile in historian polls.[20] Coverage of Harrison in historical analysis has been limited.[14]: 279–280 Early historical analysis of Harrison's performance as first lady often emphasized her role as a housekeeper, but her legacy has been reconsidered to include her advocacy for the arts, women's causes, and White House preservation.[11] A bronze statue of Harrison was placed in the Oxford Community Arts Center garden in 2018, the site previously being the location of the Oxford Female Institute.[21]

Harrison was celebrated in her day as a model of domestic life for proficiently managing the White House.[1]: 153 In her role as White House hostess, she is described as unsuccessful, being unable to maintain good relations with Washington society and lacking the grandeur associated with past first ladies. Her desire for privacy often superseded her duties as the public face of the White House.[5]: 155–156 In particular, she was often compared to and sometimes overshadowed by her immediate predecessor Frances Cleveland, who was much younger and widely beloved.[8]: 189

Contemporary historians recognize Harrison for her renovation work in the White House, and her renovation projects had a major effect on future presidencies. Her rejected proposal to remodel the White House would be adapted into a future renovation plan, resulting in the construction of the building's East Wing and West Wing.[8]: 186 Frances Cleveland, who managed the White House both before and after Harrison, expressed her approval of the renovations.[5]: 154 Harrison's work remains one of the most comprehensive projects to affect the White House.[5]: 156 Her measures to preserve White House china and furnishings have established long-standing collections.[8]: 190

See also

- Letitia Christian Tyler – wife of John Tyler who also died while serving as first lady

- Ellen Axson Wilson – wife of Woodrow Wilson who also died while serving as first lady

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Schneider, Dorothy; Schneider, Carl J. (2010). "Caroline (Carrie) Lavinia Scott Harrison". First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Facts on File. pp. 147–154. ISBN 978-1-4381-0815-5.

- ^ a b c d e Moore, Anne Chieko (2005). Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison. Nova History Publication. ISBN 1-59454-099-3.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2011). The Civil War Era and Reconstruction: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural and Economic History. Vol. 1. Sharpe Reference. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7656-8257-4.

- ^ Brown, John Howard, ed. (1900). Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States. Vol. III (University ed.). p. 555.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Watson, Robert P. (2001). "Caroline Lavinia Scott Harrison". First Ladies of the United States. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 151–157. doi:10.1515/9781626373532. ISBN 978-1-62637-353-2. S2CID 249333854.

- ^ a b c d e f Foster, Feather Schwartz (2011). "Caroline Harrison". The First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Mamie Eisenhower, an Intimate Portrait of the Women Who Shaped America. Cuberland House. pp. 83–88. ISBN 978-1-4022-4272-4.

- ^ a b Diller, Daniel C.; Robertson, Stephen L. (2001). The Presidents, First Ladies, and Vice Presidents: White House Biographies, 1789–2001. CQ Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-56802-573-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Hendricks, Nancy (2015). "Caroline Harrison". America's First Ladies. ABC-CLIO. pp. 186–192. ISBN 978-1-61069-882-5.

- ^ a b c d e Longo, James McMurtry (2011). From Classroom to White House: The Presidents and First Ladies as Students and Teachers. McFarland. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0-7864-8846-9.

- ^ Sherzer, Jane (September 7, 1912). "A Pioneer Woman's College". The Outlook. pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d e Scherber, Annette (June 28, 2017). ""Underrated" First Lady Caroline Scott Harrison: Advocate for the Arts, Women's Interests, and Preservation of the White House". Indiana History Blog. Indiana State Library and Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Gould, Lewis L. (1996). American First Ladies: Their Lives and Their Legacy. Garland Publishing. p. 265. ISBN 0-8153-1479-5.

- ^ Caroli, Betty Boyd (2010). First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 108–111. ISBN 978-0-19-539285-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Scofield, Merry Ellen (2016). "Rose Cleveland, Frances Cleveland, Caroline Harrison, Mary McKee". In Sibley, Katherine A. S. (ed.). A Companion to First Ladies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 265–282. ISBN 978-1-118-73218-2.

- ^ Beasley, Maurine H. (2005). First Ladies and the Press: The Unfinished Partnership of the Media Age. Northwestern University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8101-2312-0.

- ^ Griffin, Lynne; Kelly McCann (1992). The Book of Women. Holbrook, MA: Bob Adams, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 1-55850-106-1.

- ^ DeGregorio, William A. (1993). The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents (4th ed.). Wings Books. p. 334. ISBN 0-517-08244-6.

- ^ a b c Lindsay, Rae (2001). The Presidents' First Ladies. Gilmour House. p. 60. ISBN 0-965-37533-1.

- ^ a b "White House Repairs". The Sunday Herald. June 14, 1891. p. 17.

- ^ Ranking America's First Ladies (PDF) (Report). Siena Research Institute. 2003.

- ^ Snyder, Lauren (October 12, 2018). "Caroline Scott Harrison, a First Lady from Oxford, Returns Home in Bronze". Oxford Observer. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

External links

- "First Lady Biographies: Caroline Harrison" Archived May 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, First Ladies Library website

- Caroline Harrison at C-SPAN's First Ladies: Influence & Image

- 1832 births

- 1892 deaths

- 19th-century American educators

- 19th-century American women educators

- 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Benjamin Harrison

- Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery

- First ladies of the United States

- Presidents General of the Daughters of the American Revolution

- Harrison family of Virginia

- Tuberculosis deaths in Washington, D.C.

- Miami University alumni

- People from Oxford, Ohio

- American women music educators

- American music educators

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !