Clyde Bellecourt

Clyde Bellecourt | |

|---|---|

Neegonnwayweedun | |

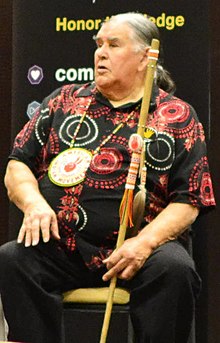

Bellecourt speaking at ASU in 2016 | |

| Born | May 8, 1936 |

| Died | January 11, 2022 (aged 85) Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Occupation | Civil rights organizer |

| Known for | Co-founding the American Indian Movement |

| Spouse |

Peggy Sue Holmes (Hakida)

(m. 1965) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | Vernon Bellecourt (brother) |

Clyde Howard Bellecourt (May 8, 1936 – January 11, 2022) was a Native American civil rights organizer.[2] His Ojibwe name is Nee-gon-we-way-we-dun, which means "Thunder Before the Storm".[3] He founded the American Indian Movement (AIM) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1968 with Dennis Banks, Eddie Benton-Banai, and George Mitchell. His elder brother, Vernon Bellecourt, was also active in the movement.

Under Bellecourt's leadership, AIM succeeded in raising awareness of tribal issues. AIM shone a light on police harassment in Minneapolis. Bellecourt founded successful "survival schools" in the Twin Cities to help Native American children learn their traditional cultures. In 1972, he initiated the march to Washington, D.C. called the Trail of Broken Treaties, hoping to renegotiate federal-tribal nations' treaties. Non-profit groups he founded are designed to improve economic development for Native Americans.[4]

Early life

Clyde Bellecourt was the seventh of twelve children born to his parents, Charles and Angeline, on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota. Among his older siblings was brother Vernon Bellecourt.[5] The reservation was impoverished and his home had no running water or electricity.[3]

In his youth, Bellecourt fought against authorities, believing that they did not treat his family and other Indians with respect.[6] His parents told him to think about his education and do as well as he could.[6] The years in school were not pleasant. As a boy, he attended a reservation Catholic mission school run by strict nuns of a Benedictine order.[6] Young Bellecourt snared rabbits, and harvested wild rice and sugar beets until he was 11 when he was arrested for truancy and delinquency, and sent away to the Red Wing State Training School.[7]

By the time he was released four years later, the Bellecourt family had moved to Minneapolis in the 1950s, under the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 whereby the federal government encouraged moves to settings where there might be more job opportunities.[7] They found the city difficult, and Bellecourt reacted to perceived discrimination and feeling out of place.[7]

He received detentions at school.[6] Getting involved with bad influences, Bellecourt ultimately incurred criminal charges. He was convicted and sentenced to the adult correctional facility at St. Cloud for a succession of offenses, including burglary and robbery.[6]

At the age of 25, Bellecourt was transferred to Stillwater Prison in the eponymous city of Minnesota, where he served out the remainder of his sentence.[8] There he met numerous other Native Americans, many of them also Ojibwe. Among those were Eddie Benton-Banai (Ojibwe, 1931–2020), who had started a prison cultural program called the American Indian Folklore Group[9] for Native Americans,[10] and Dennis Banks (Ojibwe, 1937–2017).[11] After working together in prison, they decided to create a similar program in Minneapolis, to aid urban Indians through exposure to their history, traditional culture, and spirituality.[6]

American Indian Movement

Bellecourt helped found AIM during a Minneapolis meeting in July 1968 with Banks and George Mitchell of the Leech Lake Reservation.[12][13] Eddie Benton-Banai, who was raised on the Lac Courte Oreilles reservation in northern Wisconsin, was also one of the founders.[10] They were discussing how to raise awareness of issues American Indians faced in the Twins Cities, and to solve those problems. Topics included police harassment and brutality against Native Americans, discrimination by employers, discrimination in school, poor housing, and high unemployment among American Indians.[12]

At first they called themselves “Concerned Indian Americans,” but changed to "aim" at the suggestion of an elder woman.[9] Banks wrote in 2004 that Bellecourt was a "man in a hurry to get things done," who "spoke with such intensity that his enthusiasm swept over us like a storm. In that moment, AIM was born."[9] Bellecourt was elected the group's first chairman, Dennis Banks field director, and Charles Deegan vice chairman.[9]

They began to monitor arrests of American Indians made by the local police department to ensure their civil rights were observed and they were treated with dignity and respect.[12] Benton-Banai had also worked on this issue before serving time in Stillwater Prison.[10]

In 1970, he led a takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) building in Littleton, Colorado, to demand that Native Americans be put in charge of the BIA. The protest spread across the country, with eight BIA offices shut down.[7]

In 1971, Bellecourt visited the Chicago Indian Village (CIV), an inter-tribal group protesting to raise awareness of and solutions for poor housing conditions for Native Americans in Chicago. The CIV had occupied the former site of a battery of Nike anti-aircraft missiles at Belmont Harbor in Chicago.[14]

The FBI was able to splinter the movement and as of the early 21st century it survives, weakened,[15] in two factions, one in Colorado and formerly led by Russell Means, and the second in Minnesota and formerly led by the Bellecourt brothers, all now deceased. The Minnesota faction is incorporated under Minnesota and U.S. law and has succeeded in several legislative and social efforts.[16] When it broke off, the Colorado faction accused the Minnesotans of various crimes: for the most part, the Bellecourts labeling themselves national AIM officers fraudulently, because national leaders do not exist in a grassroots organization.[17]

Trail of Broken Treaties

In August 1972, tribal chairman Robert Burnette of the Rosebud Reservation proposed a peaceful march on Washington, D.C., which became known as the Trail of Broken Treaties.[18] They wanted to highlight the failures of the federal government in fulfilling its treaty obligations and the widespread poverty among Native Americans.[15] The group supported establishing a Federal Indian Commission as part of the executive branch and the abolition of the BIA, among their list of demands. Organizers originally planned a peaceful tour of Washington landmarks and meeting with leading government officials to present their "20 points," as a list of their grievances and demands.[19]

Finding no accommodations elsewhere,[20] about 1,000 activists occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[citation needed] They allegedly caused extensive damage to treaty files and other records of the history between the federal government and the tribes.[15] They called for ending corruption and mismanagement within the BIA.[21][22][23] Bellecourt, Banks and other AIM leaders negotiated with the federal government.[24] Following an occupation from November 3 until November 9,[20] the Nixon administration gave the activists $66,000 in transportation costs in exchange for a peaceful outcome.[citation needed]

Wounded Knee Occupation

In 1973 AIM activists were invited to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota by its local civil rights organization to aid in securing better treatment from state and local law enforcement in the border towns, which had been slow to prosecute attacks against Lakota. They were also protesting the failed impeachment of the elected tribal chairman, Richard Wilson, who was opposed by many on the reservation, and poor living conditions. AIM occupied Wounded Knee, a town in the reservation that is the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. Soon they were surrounded by FBI agents and U.S. marshals. Two people were killed in the 71-day armed standoff.[4]

Bellecourt became a negotiator.[4] Eventually, he, Russell Means, and Carter Camp held a meeting with a representative for U.S. President Nixon,[25] when they negotiated an audit of Wilson's finances and an investigation of his private militia, the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs).[6]

After leaving Pine Ridge, Bellecourt and Means were arrested in Pierre, South Dakota; the court set a bond at $25,000.[25] They were served a restraining order against approaching closer than five miles to the town of Wounded Knee.[25] After being released on bond, Bellecourt went on a fundraising tour across the United States, trying to raise money for the activists still occupying Wounded Knee.[25] Charges against Means and Banks were dropped, and none were brought against Bellecourt.[7]

Shot, reported dead

At least three versions of this story exist, and all agree Bellecourt was unarmed.[26] He was steadfastly opposed to violence and did not carry a weapon at Wounded Knee.[26] Carter Camp, who had just been elected AIM national chairman,[3] shot Bellecourt at point-blank range on the Rosebud Reservation in 1973. Later Bellecourt wrote in his autobiography that he believed Camp was working with the FBI, an opinion shared with others; however Camp's name was since cleared in this respect.[26] The bullet pierced his pancreas, just missing his spine. News reported him dead however he was flown from South Dakota to the University of Minnesota hospital where he recovered.[7]

After the occupation of Wounded Knee ended, Bellecourt hosted seminars and other public appearances. He claimed that "the seminar represents the beginning of an educational effort by AIM and a turning point for the organization, which hopes to avoid violent confrontations in the future." Throughout the rest of his speaking tour about Wounded Knee and the BIA takeover, Bellecourt would maintain that Christianity, the Office of Education, and the Federal government were enemies to Indians.[9] He defended AIM actions at the BIA and Wounded Knee.[6] Bellecourt said, "We are the landlords of the country, it is the end of the month, the rent is due, and AIM is going to collect."[3]

In 1977, Bellecourt traveled to the United Nations where he testified on U.S. mistreatment of Native Americans.[7]

1980s drug charges

In December 1985, Bellecourt met with an undercover agent in a laundry room at Little Earth of United Tribes, a south Minneapolis housing development, and sold her LSD. Bellecourt was arrested, along with a group of Indian and non-Indian associates, in possession of an estimated $125,000 worth (5000 "hits") of LSD and other "hard" drugs (cocaine). Charged on eight counts of being a major drug distributor, each compounded by a conspiracy charge, Bellecourt accepted a plea bargain deal. He confessed, entering a guilty plea to lesser felonies. Federal District Judge Paul A. Magnuson sentenced him to five years' imprisonment (of which he served less than two). Bellecourt had become addicted to drugs before his arrest; he later said that the conviction and imprisonment helped him break the addiction.[8][27][17]

Bellecourt described this time with regret, "I should never have gotten involved in drug dealing, but I did. I've made mistakes in my life, and this one was one of the worst; I have had to make peace with it."[28]

Heart of the Earth

Bellecourt founded the Heart of the Earth Survival School in 1972, which was approved for 501(c)(3) status in 1974. The passage of the American Indian Education Act enabled Native American tribes and related groups to contract to operate BIA funded schools for Native American students. Heart of the Earth won such contracts for 24 years. The school covered students from preK-12. In the 1980s, it added adult learning and prison programs. Heart of the Earth has coordinated a national law education program.[29]

Developed as an independent charter school in 1999, when it was considered an option of the public school district, Heart of the Earth took over ownership of its site. It continued to offer a wide variety of independent cultural programs, awarded scholarships to Indian students, and developed indigenous language research.[29] The charter was revoked in 2008 because serious financial irregularities were discovered, and the school was closed.[30]

In all, more Native American students graduated from the school in its 40-year history than from all Minneapolis Public Schools combined.[29]

Later activities

In 1993, Bellecourt and others led protests against police brutality in Minneapolis when two intoxicated Native men were driven to the hospital in the trunk of a squad car.[7][28]

Bellecourt continued to direct national and international AIM activities. He coordinated the National Coalition on Racism in Sports and the Media, which has long protested sports teams use of Native American mascots and names, urging them to end such practices; the Washington Redskins finally dropped their mascot in 2020 in response to years of protests. He also led Heart of the Earth, Inc., an interpretive center located behind the site of AIM's former 'survival school', which operated from 1972 to 2008 in Minneapolis.[31]

Other organizations founded in part by Bellecourt include the Elaine M. Stately Peacemaker Center for Indian youth; the AIM Patrol, which provides security for the Minneapolis Indian community; the Legal Rights Center; MIGIZI Communications, Inc.; the Native American Community Clinic; Women of Nations Eagle Nest Shelter; and Board of American Indian OIC (Opportunities Industrialization Center), a job program to help Native Americans get full-time jobs.[32]

In 2016, Bellecourt participated in resistance to an underground oil pipeline at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation.[25]

Personal life and death

Bellecourt lived in Minneapolis with his wife, Peggy. They had four children.[33] He died of cancer[34] on January 11, 2022, at the age of 85.[35] At the time of his death, Bellecourt was the last surviving co-founder of the American Indian Movement.[36]

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz stated, "Clyde Bellecourt sparked a movement in Minneapolis that spread worldwide. His fight for justice and fairness leaves behind a powerful legacy that will continue to inspire people across our state and nation for generations to come".[37] According to Minnesota Lt. Governor Peggy Flanagan, Neegawnwaywidung was a "civil rights leader who fought for more than a half-century on behalf of Indigenous people in Minnesota and around the world. Indian Country benefited from Clyde Bellecourt's activism".[37]

References

- ^ a b Saint Louis, Christina (April 4, 2022). "Peggy Bellecourt, a leader of the American Indian Movement for Indigenous civil rights, dies at 78". Star Tribune. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ "American Indian Movement Leader Clyde Bellecourt Dies at 85". US News. Associated Press. January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, Sam (January 13, 2022). "Clyde Bellecourt, a Founder of the American Indian Movement, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Clyde Bellecourt". MPR archive, Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Furst, Randy. "As his body gives out, AIM co-founder Clyde Bellecourt keeps his eye on the fight". StarTribune. No. February 19, 2019. Tribune Media Company LLC. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Clyde Bellecourt, Cofounder of AIM". AAANativeArts. April 20, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nesterak, Max (January 11, 2022). "American Indian Movement co-founder Clyde Bellecourt, 'Neegonnwayweedun,' dies at 85". Minnesota Reformer. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Bury My Heart | City Pages". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Davis, Dr. Julie L. "Not Just a Bunch of Radicals: A History of the Survival Schools". Regents of the University of Minnesota. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c Forliti, Amy; Fonseca, Felicia (December 2, 2020). "American Indian Movement co-founder Benton-Banai dies at 89". Associated Press. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ D'Arcus, Bruce (May 2010). "The Urban Geography of Red Power: The American Indian Movement in Minneapolis-Saint Paul, 1968–70". Urban Studies. 47 (6): 1241–1255. Bibcode:2010UrbSt..47.1241D. doi:10.1177/0042098009360231. JSTOR 43079911. S2CID 146782977.

- ^ a b c Davis, Dr. Julie L. (2013). Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-8166-7429-9.

- ^ "Timeline". American Indian Movement. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ LaGrand, James B. (2002). Indian Metropolis: Native Americans in Chicago 1945–75. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 241. ISBN 9780252072963.

- ^ a b c Simpson, Bob (November 19, 1972). "Native Americans Take Over Bureau of Indian Affairs: 1972". The Montgomery Spark. Retrieved January 16, 2022 – via The Washington Area Spark.

- ^ ""American Indian Movement" Extremist Groups: Information for Students". Encyclopedia.com. December 29, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ a b "1994 Charges Against the Bellecourts". Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Blair, William M. (October 31, 1972). "Indians to Begin Capital Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Trail of Broken Treaties 20-Point Position Paper - An Indian Manifesto". AIM Movement. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Cobb, Daniel (October 2, 2021). "The Trail of Broken Treaties and Occupation of Wounded Knee". The Teaching Company. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "Framing Red Power". www.framingredpower.org. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Trail of Broken Treaties 20-Point Position Paper - An Indian Manifesto". www.aimovement.org. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Dee (November 24, 1974). "Behind the Trail Of Broken Treaties An Indian Declaration of Independence. By Vine Deloria Jr. 263 pp. New York: Delacorte Press. $8.95". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Clyde Bellecourt, Dennis Banks. "Trail Of Broken Treaties," exhibits. Gilbert Frazier, Feather Films. Event occurs at 3:40. Retrieved January 17, 2022 – via University of Georgia, Wilson Center.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson, Darren (January 11, 2022). "Clyde Bellecourt, One of Original Founders of the American Indian Movement, Passes Away". Native News Online. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Matthiessen, Peter (1992). In the Spirit of Crazy Horse. Viking Press. pp. 84–86. ISBN 0140144560.

- ^ Diaz, Kevin (December 23, 2010). "Minnesotan now nation's top drug cop". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ a b Furst, Randy (January 11, 2022). "Clyde Bellecourt, AIM co-founder and longtime civil rights leader, dies". Star Tribune. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Lurie, Jon. "Heart of the Earth Survival School". MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Ross, Jenna (June 1, 2009). "Minneapolis charter school director allegedly embezzled $1.38 million". Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Archived from the original on June 14, 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ Indian Nations of North America. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. 2010.

- ^ Mosedale, Mike (February 16, 2000). "Bury My Heart", Archived May 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine City Pages.

- ^ Olson, Rochelle (December 25, 2012). "Minneapolis Indian activist arrested at Crystal Court on Christmas Eve". Star Tribune.

- ^ "American Indian Movement co-founder Clyde Bellecourt dies at 85". January 11, 2022. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "American Indian Movement leader Clyde Bellecourt dies at 85". Associated Press. January 11, 2022. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023.

- ^ Braine, Theresa (January 11, 2022). "Clyde Bellecourt, co-founder of American Indian Movement and longtime activist activist, dies at 85". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Alvarado, Caroll (January 12, 2022). "Clyde Bellecourt, Native American civil rights leader, dies at 85". CNN. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

Further reading

- "Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan Moves on Washington D.C.", Akwesasne Notes 4.6 (1972): 1–6.

- Davis, Julie. Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2013)

- Heppler, Jason A., "Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/21

- Smith, Paul C., and Robert A. Warrior. Like a Hurricane. New York: The New Press, 1996. 128–32, 242–43, 256.

External links

- Clyde Bellecourt biography, International Indian Treaty Council and AIM Speakers Bureau

- Thunder before the Storm: The Autobiography of Clyde Bellecourt. Project MUSE, Johns Hopkins University. 2016. ISBN 9781681340203.

- 1936 births

- 2022 deaths

- 20th-century Native Americans

- Native American activists

- Members of the American Indian Movement

- Activists from Minneapolis

- White Earth Nation people

- Deaths from cancer in Minnesota

- Prisoners and detainees of Minnesota

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

- Native American people from Minnesota

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !