Evolution of the Dutch colonial empire

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

The Dutch Empire is a term comprising different territories that were controlled by the Netherlands from the 17th to 20th centuries. They settled outside Europe with skills in trade and transport.[1] In the late 16th century, the Netherlands reclaimed their lead at sea, and by the second half of the 17th century, dominated it. This hundred-year period is called the Dutch Golden Age. The Dutch built their empire with corporate colonialism by establishing the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (GWC), following Britain's footsteps, which led to war between both empires.[2][3] After the French Revolutionary Wars, the Netherlands lost most of its power to the British after the French armies invaded the Netherlands and parts of the Dutch colonies.[4] Hence, Dutch leaders had to defend their colonies and homeland. Between 1795 and 1814, the French restored the VOC in Indonesia and Suriname which remained under Dutch control.[5]

The global expansion of the Dutch Empire

By the 17th century, there was a beginning of revolutionary thought in Europe.[6][7] This had an impact on the European politics, culture, and science, eventually leading to the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century.[8] Due to Enlightenment thinking and science, European economies developed faster than the rest of the world. Therefore, a primary consequence was the beginning of modern imperialism and the rise of the colonial states. This led to the rise of the Dutch Empire.[9] The Dutch Empire lasted for three and a half centuries, both in the east and west of the globe. The majority of the Dutch Empire's economy was concentrated on the East Indies and only a small part of their focus was on the West Indies. By the 19th century, the Netherlands started losing most of its possessions in Asia, while Great Britain managed to become the undisputed successor that took over most of the Dutch East India Company's assets. For that reason, Dutch trade in the East Indies weakened while the British took control of Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Dutch East India Company (VOC)

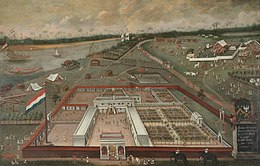

The VOC name came from the Dutch East Indies Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compangnie).[10] This trading company was founded in the Dutch Republic, started in 1602 to protect their trade along the Indian Ocean. The VOC main trade location was in Indonesia. The company became the only power of the peninsula. According to the Dutch colonial archive, the communication between Batavia and the government in Hague were disrupted during the British captured and occupied the Dutch East Indies.[11] However, it was restored when Java returned to the Dutch in 1816, after five years under British rule. The structure of the company factories was to control the supplies of some products such as cloves, nutmeg and mace.[12][13] They used a forceful system as a form of tax, to control the locals to sell at a set price. The purpose of this system was to bring all these products to Europe; and VOC profits were only for the company not to the indigenous traders.[14]

Dutch West India Company

The GWC name came from the Dutch West India Company (Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie). When the VOC took control in the eastern shores, Amsterdam decided to establish the GWC. The Dutch arrival in Africa and the Americas had a great effect on the political culture of both countries. According to historians, the Dutch played an important role in the Atlantic countries. They brought their culture and politics to Africa and the Americas. The Dutch were at war with Spain; but Amsterdam was only interested in taking over the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and South America, the reason behind the war with Spain, due to the Spanish invasion of the southern Netherlands between the 15th and the 16th centuries. The government did not care about investment or trade, which angered the merchants because they did not have any financial guarantees.[15] It was obvious that the West India Company was interested in war more than trade. On the other hand, Spain did not intend to wage war against the Dutch, as a result, the Spanish made them sign a truce to force the Dutch to withdraw from the Americas. The Dutch were not impressed with the Spanish ban on their trade, except the Dutch were more knowledgeable in map-making across the globe. The most famous Dutch cartographer of the 17th century was Hessel Gerritsz.

Economy

The demand for wool could not meet with the native production in the Netherlands. By the 12th century, Flemings imported a large amount of English wool.[16] Textile industries in the southern Netherlands became the largest manufacturers of cloth as well as being front-runners of crafts in the thirteenth century. The Dutch Republic was more successful in cloth-making, with Flanders[17] being the most favoured throughout all of Europe.[18] Whereas, in the other European countries, they used fake textiles trying to copy Flanders work, most of the Dutch textile industry were mastered by Romans. By the end of the 15th century, Flanders was not the sole manufacturer anymore. When the demand grew for textile, the English imported wool which was the high-quality product and the most demanded all over Europe. Flanders lost its position in textile industries. However, the economy was built on fishing. Agriculture and fishing were the most essential for the Dutch economy. The Dutch were successful in the fishing industries in the Baltic and North Seas between the 15th and 16th centuries, nearly a hundred years before they established their empire in the 17th century. As the urban population increased during the 17th century, there was a dramatic rise in demand for fruit and vegetables. As a result, many farmers turned to gardening as well as animal production, considering Holland's weather and soil was ideal to grow cattle. Agriculture was the biggest section of Dutch economy. Though grain production could not cover the demands, due to migrations from the southern provinces. Consequently, the Dutch started to import grains from the Baltic, and sure enough the main trade considered the main source of the Dutch employment in the eighteenth century. Due to the early success that the Dutch had with the Baltic trade, Dutch ships expand their trade to east Russia, south to the Mediterranean. By the 17th century, they moved their trade to the American and Asian markets. They also expanded to Guinea trade ignoring the slave trade, as it was the Portuguese trade. There was a big rivalry between trade companies from European Asia to America. The Dutch trade faced stark competition from the Portuguese in Asia and English in Africa and America. As they controlled the trade road from the Indian to Atlantic Oceans. Until the VOC was formed, it became the first and most big merchant ships in Asia. Even then they had stiff competition with the English East India company. Although the economy was built on fishing, the agriculture during the fifteenth century, animal farming was another reason for building the Dutch economy.[18] Dutch cattle were well cared for, during that period urban population grew and farmers grew fruits and vegetables to supply the cities. The success they built in the Baltic trade gave the Dutch the ability to increase their trade to Asia and the Americas.[18]

Africa

South Africa

In 1652, the Dutch East India Company under Jan van Riebeeck established a resupply station at the Cape of Good Hope, situated halfway between the Dutch East Indies and the Dutch West Indies. Great Britain seized the colony in 1797 during the wars of the First Coalition (in which the Netherlands were allied with revolutionary France), and annexed it in 1805.[19] The Dutch remained in South Africa until the Boer Wars broke out.[20] The Dutch colonists in South Africa remained after the British took over and later made the trek across the country to Natal. They were involved in the Boer Wars against the British and are now known as Boers.

West Africa

The Dutch had several possessions in West Africa. These included the Dutch Gold Coast, the Dutch Slave Coast, Dutch Loango-Angola, Senegambia, and Arguin. They built their first two forts on the Gold Coast in 1598 at Komenda and Kormantsil (in present-day Ghana). They expanded their presence in the following centuries. In 1872, they sold the Dutch Gold Coast to the British.

East Africa

Mauritius is an island east of Madagascar, off Africa's southeast coast. Dutch Mauritius was an official settlement of the Dutch East India Company on the island of Mauritius between 1638 and 1710.

Asia

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies comprised and formed the basis of mostly the later Indonesia. The first Dutch conquests were made among the Portuguese trading posts in the Maluku "Spice Islands" in 1605. The Spice Islands were out of the way for the Dutch trade routes to China and Japan, so Jayakarta on Java was captured and fortified in 1619. As "Batavia" (now Jakarta), it became the Asian headquarters of the East India Company (VOC). The company administered the islands directly on a for-profit model that restricted most of its attention to Java, southern Sumatra, and Bangka. English incursions were curtailed by the 1623 Amboyna massacre but the attack left bad blood and prompted a series of Anglo-Dutch wars. The company and its territories were nationalized in 1795 after British attacks effectively bankrupted it. The Dutch Malacca was part of the Dutch East Indies governorate between 1818 and 1825. However, the Dutch preferred Batavia (present-day Jakarta) as their economic and administrative centre in the region and their hold in Malacca was to prevent the loss of the city to other European powers and, subsequently, the competition that would come with it. In 1825, based on the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, the Dutch have ceded Malacca to the United Kingdom that have consolidated modern-day rule to the Malacca state of Malaysia. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Dutch expanded throughout the archipelago. Following the 1940 German occupation of the Netherlands and the 1942 Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies during World War II,[21] Indonesian independence was declared in August 1945 and – following a prolonged revolution – recognized in December 1949.

Dutch New Guinea was retained separately until 1962, when it was transferred to Indonesia under pressure from the United States amid the escalation of the Vietnam War.

Dutch India

Dutch India was also composed of colonies and trading posts administered initially by the East Indies Company (VOC) and then directly by the Dutch government after the VOC's collapse.

Coromandel was the major Dutch colony on the mainland. It grew from the fort at Pulicat (Geldria) captured from the Portuguese in 1609. It comprised India's southeastern Coromandel coast across from Ceylon. Surat (Suratte) administered Dutch outposts in Gujarat after 1616. Outposts in Mughal Bengal (Bengalen) were consolidated after Chinsura (Gustavius) was fortified in 1635. Malabar was conquered from the Portuguese in the 1660s and administered from Cochin.

Amid the Napoleonic Wars, Malabar and Suratte were yielded to the British in 1795; Ceylon in 1802; and Bengal and Coromandel in 1824.

Ceylon

Ceylon (Zeylan; modern Sri Lanka) was the principal interest of the Dutch in India: it provided cinnamon and elephants and serviced trade between South Africa and the East Indies. Buddhists, Muslims and Hindus were struggling against the Portuguese who were trying to convert the people to Christianity. Where the Dutch were interested in trade more than religion, as a result, they took over and made Ceylon their major trading post. The VOC successfully wrested it from Portuguese control during the 1630s, 1640s, and 1650s although, like the Portuguese, they were never able control the interior of the island. In 1796, Britain took control of all the Dutch positions.[22]

Formosa

Formosa was the Dutch colony on Taiwan. It was based at Fort Zeelandia from 1624 to 1662, when Koxinga conquered the island. The island was a source of sugarcane and buckskin, as well as an entrepot for merchants from the Chinese mainland.

Malacca

Malacca was an important port on the western Malay Peninsula controlling the Strait of Malacca. It was seized from the Portuguese in 1641. During the Napoleonic Wars, it was yielded to Britain in 1806; it was later returned in 1816 and finally ceded again in 1824.

Iran

An asterisk (*) designates a trading post.

Band-e Kong (1690)*

Bandar-e Abbas (1623–1758)* The Dutch East India Company founded an office in Gamron in 1623. Here they purchased wool and attar of roses and above all silk. They sold spices, cotton fabrics, porcelain, opium, and Japanese lacquer work. Gamron had a garrison comprising around 20 European employees and 20 Persian staff. In 1729 the Dutch attempted, without success, to move their factory from Bandar-e Abbas to the island of Hormuz. In 1758 the company decided to close the station at Bandar-e Abbas.

Bushehr (1738–1753)*

Esfahan (1623–1747)* In 1623 Huybert Visnich established a trading station in Isfahan and concluded a commercial treaty with the Shah. Esfahan was the capital of the kingdom of Persia. The Dutch East Indies Company bought silk from the Shah in exchange for spices and military protection. They were obliged to maintain an office in Esfahan due to the endless negotiations with the Shah about trading concessions. In 1722, Esfahan was conquered by the Afghans. During this time the Dutch were kept virtual prisoners in their factory. In 1727 the factory had to be abandoned because the inner city was to be reserved for Afghans only. The Dutch staff moved to Jolfa. In 1747 the Dutch East India Company office was closed.

Kerman (1659–1744)* A Dutch trading station was opened at Kerman in 1659. It remained in operation, with interruptions, until 1744. The town of Kerman was known for its wool trade.

Khark (1753–1766) Khark is an island in the north of the Persian Gulf near Basra. In Khark the Baron Tido von Kniphausen, formerly Dutch East India Company agent in Bassora, built Fort Mosselstein in 1753 where Javanese sugar and Indian textiles were offered for sale. In 1766 the fort was plundered by the Persian army.

Lar (1631)

Qeshm (1685)

Shiraz (???)

Iraq

Al Basrah (1645–1646, 1651)*

Pakistan

The Dutch had a trading office in the city of Sindi (now Thatta) from 1652 to 1660.[23]

Yemen

Aden (1620)* On 22 August 1620, the Dutch ship T Wapen van Zeelandt reached Aden. Here the Dutch immediately rented a house. When the ship left Aden, five servants and a supply of goods (worth about 42.000 guilders) were left in the trading post under the charge of Harman van Gil. Van Gil went to Sana'a where Muhammad Basha granted to the Dutch permission to build a trading office in Mocha. In November/December 1620 Van Gil transferred the company's goods to Mocha and closed the temporary office in Aden.

Al Mukha (1621–1623, 1639–1739)* Van Gil arrived in Mocha on 28 January 1621 and there he founded a Dutch trading office. Harman van Gil died in July 1621. Willem Jacobsz de Milde was appointed chief of the trading office. The trading office was closed in April 1623 due to problems with the Yemenite governors. It was reopened in 1639–1739.

Ash Shihr (1614–1616)*

Bangladesh

Dhaka (1602–1757)*

During the period of Proto-industrialization, the empire received 50% of textiles and 80% of silks import from the India's Mughal Empire, chiefly from its most developed region known as Bengal Subah.[24][25][26][27]

In the 18th century the Dutch Colonial Empire began to decline as a result of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War of 1780–1784, in which the Netherlands lost a number of its colonial possessions and trade monopolies to the British Empire and the conquest of the wealthy Mughal Bengal at the Battle of Plassey.[28][29]

Oman

Muscat (1674)*

Burma

Bandel (1608–1631, 1634)*

Syriam (1635–1679)*

Ava (1635–1679)*

Mandalay (1625–1665)*

Martaban (1660)*

Pegu (???)*

Thailand

Ayutthaya*

Bangkok*

Nakhon Si Thammarat*

Pattani*

Phuket*

Songkhla*

Malaysia

Melaka*

Kuala Kedah*

Kuala Linggi

Kuala Selangor

Tanjung Putus*

Ilha das Naus

Kota Belanda (1670–1743, 1745–1748) The origins of this fort can be traced back to 1670. At this time, the Dutch had a monopoly on the export of tin in Perak. The fort was built to protect the tin trade. It is located in the fishing village of Teluk Gedung on Pangkor Island. An early fort was built in 1651 but was destroyed. In 1670, Batavia ordered the construction of a new wooden fort. Ten years later it was replaced by a brick one. In 1690, the Malays under the leadership of Panglima Kulup attacked, damaging the fort and killing several Dutchmen. The settlement was temporarily abandoned until 1743, when the Dutch returned and repaired it. The Dutch stationed 60 soldiers here, including of 30 Europeans.

In 1748, the Dutch built another fort near the Perak River. Following this the Dutch administrators ordered the abandonment of this fort. In 1973, the Museums Department rebuilt the fort and it is now a tourist attraction.

Cambodia

Phnom Penh*

Laauweck (1620–1622, 1667)* The town of Lawec in Cambodia was situated halfway along the Mekong River on the way to Phnom Penh. The Dutch East India Company set up a trading post at Lauweck in 1620, but the trade there proved disappointing, and just two years later the company shut the post down. A new Lawec trading post was opened in 1636, and then sold to the British in 1651, with discontinuities corresponding to the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the era. Meanwhile, "From 1636 to 1670 the Dutch merchants lived at Udong on a semi-permanent basis."[1] but in 1667 the Company left Cambodia durably (to continue regional trade from their expanding holdings in what is now Indonesia). Besides deer hides and ray skins, Cambodia functioned mainly as a source of provisions for Batavia such as rice, butter, salted pork, and lard.

Vietnam

Hanoi (1636–1699)* Towards the end of the 1630s, the Company signed an agreement with the king of Tonkin and opened a trading post in or near today's Hanoi. The country was a major silk producer. The silk which the Dutch East India Company bought there was particularly valuable for trade with Japan. The Company maintained a trading post in Tonkin from 1636 to 1699. This trading post was run by an 'opperhoofd' or supervisor.

Hoi An*

China

Fuzhou (????-1681)* After the loss of Taiwan to the Chinese in 1662, the Dutch East India Company tried to gain access to the Chinese porcelain and silk trade at the port of Fuzhou. The company's attempts to trade there were hampered by a string of bureaucratic restrictions. Although the trading post at Fuzhou barely made a profit, the Company kept it open until 1681.

Huangpu (1728) Whampoa, an island situated in the Zhujiang river, served as the harbour for the city of Canton. A Dutch warehouse was built here.

Canton (1749–1803)* Tea and porcelain were the principal products purchased by the Dutch East India Company in Canton (now known as Guangzhou). In the 18th century the Company rented permanent premises in Canton, next to the building occupied by the British.

In 1622, some Dutch East India Company (VOC) ships attempted to set up a trading post at Fat Tong Mun (佛堂門) (now in Hong Kong) after the Dutch settled in present-day Tainan. The Dutch then sailed their ships via present day Victoria Harbour to Nantou in Shenzhen. The Dutch left for Portuguese Macau and finally Taiwan after violent crashes with the locals.[30]

Japan

Firando (1609–1641)*

Deshima (1641–1853)* Initially the Dutch maintained a trading post at Hirado, from 1609 to 1641. The Japanese granted the Dutch a trade monopoly in Japan from 1641 to 1853, but solely on Deshima, an artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki. During this period they were the only Europeans allowed into Japan. Chinese and Korean traders were still welcome, though restricted in their movements.

Europe

Belgium

The Netherlands were granted control of the Southern Netherlands after the Congress of Vienna. The Southern Netherlands declared independence in 1830 (the Belgian Revolution), and its independence was recognized by the Netherlands in 1839, giving birth to the new country of Belgium. As part of the Congress of Vienna, King William I of the Netherlands was made Grand Duke of Luxembourg, and the two countries united into a personal union.

Luxembourg

The independence of Luxembourg was ratified in 1869. When William III of the Netherlands died in 1890, leaving no male successor, the Grand Duchy was given to another branch of the House of Nassau.

North America

New Netherland

New Netherland (Nieuw-Nederland) comprised the areas of the northeast Atlantic seaboard of the present-day United States that were visited by Dutch explorers and later settled and taken over by the Dutch West India Company. The settlements were initially located on the Hudson River at Fort Nassau (1614–7) in present-day Albany, New York (later resettled as Fort Orange in 1624), and New Amsterdam, founded in 1625 on Manhattan Island. New Netherland reached its maximum size after the Dutch absorbed the Swedish settlement of Fort Christina in 1655, thereby ending the North American colony of New Sweden.

New Netherland itself formally ended in 1674 after the Third Anglo-Dutch War. Dutch settlements passed to the English crown. The treaty was that each party would hold on to their land, as the Anglo-Dutch war ended, the English conquered New Amsterdam of Peter Stuyvesant including Manhattan Island.[31] Amsterdam city is today called New York.[32] The treaty forged by the Dutch and English stated that each party would hold onto any lands held or conquered at the time of the Treaty of Breda which had ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War. There was no exchange of lands. Hence, the English held onto New Amsterdam (including Manhattan Island and the Hudson River Valley), and the Dutch spoils included Dutch Guiana in South America, and the group of islands in the East Indies known as the Spice Islands (now called Maluku Islands) that were the source of the valuable spice nutmeg. These islands were the only place in the world where the nutmeg tree was found at that time.

Dutch West Indies

The Dutch Antilles (Nederlandse Antillen) comprised various islands around the Caribbean principally colonized or seized by the Dutch from the Spanish. The first settlement was at Saint Martin in 1620. Former territories include the Dutch Virgin Islands (Nederlandse Maagdeneilanden) settled in 1648 but seized by the English in 1672 and New Walcheren (Nieuw-Walcheren) on Tobago held at various times between 1628 and 1677.

Six of the original islands remain part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to this day. Three – Aruba,[33] Curaçao, and St. Maarten – are counted as "countries" within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, while the BES Islands – Bonaire, Saba, and St. Eustatius – are counted as special municipalities of the Netherlands proper within the country and overseas territories under the EU.

Oceania

New Holland

New Holland was a nominal Dutch claim over western Australia. Although no formal colonization attempt was ever made, many places along the northwest coast retain Dutch names. Numerous Dutch ships on their way to the Dutch East Indies such as the Batavia were wrecked off the coast. Later British explorers also claimed to discover small pockets of aborigines with blonde hair and blue eyes.

Van Diemen's Land

Another Dutch claim in present-day Australia, that to Van Diemen's Land, dated from 1642 when Abel Tasman claimed the present-day island of Tasmania that now commemorates his name. It too was never colonized (or even re-visited by later Dutch explorers).

South America

Suriname

Suriname (Surinam) was originally established as the English colony of Willoughbyland by Lord Willoughby in 1650. The colony was captured by a Dutch force on 26 February 1667 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Under the terms of the treaties of Breda and Westminster, the English government accepted the loss of Suriname in exchange for receiving New Netherland (which they renamed New York) in North America. Slavery in Dutch Suriname was abolished in 1873, following a decade-long transition period. Suriname remained a Dutch colony until the German occupation of the Netherlands during World War II, during which the importance of its aluminium mines prompted its occupation by American troops. After the war, Suriname was returned to Dutch rule but promoted to a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1954. It was granted full independence in 1975.

Suriname was known for its valuable sugar plantations so it fell into the hands of the Dutch in return for New Netherland when a treaty was signed in 1674.

Guyana

Pomeroon was established on its eponymous river in 1581 and destroyed by natives and Spaniards around 1596. Its original colonists fled to the ruins of an old Portuguese settlement on the island of Kyk-Over-Al in the Essequibo River and established New Zeeland (Nova Zeelandia). After a new fort was established in 1616, the colony became known as Essquibo (Essequebo). In similar fashion, settlements along the Berbice River became known as Berbice in 1627 and others along the Demerara River became Demerara (Demerary) in 1745. Pomeroon was briefly refounded in 1650 but destroyed by French pirates in 1689; later settlements were considered part of the other three colonies. Berbice was occupied by the French in 1712 during the War of Spanish Succession. It was also the site of a major slave uprising under Cuffy in 1763 and '64.

All three were repeatedly captured by the British, finally being ceded at the close of the Napoleonic Wars and reformed as Demerara-Essequibo and Berbice and then united as British Guiana. By 1814 the Netherlands surrendered Guyana to the United Kingdom.

New Holland (Brazil)

New Holland (Nieuw-Holland) comprised territories captured from the Iberian Union in northern and northeastern Brazil, held between 1630 and 1654, and claimed until the 1661 Treaty of the Hague. The conquest was the culmination of the "Grand Design", a plan by the West India Company to control the sugar trade by seizing the rich Brazilian plantations and the African slave ports necessary to resupply their labor force. A 1624 attempt held the Brazilian capital of Salvador da Bahia for a year but failed in Africa and finally yielded to a combined Luso-Spanish force. The Battle of Matanzas Bay provided the West India Company with a huge windfall of Spanish silver, which it used to successfully renew the plan. At its height, New Holland spread from Sergipe to Maranhão. Governor Maurits successfully managed the colony for years but, upon his recall to the Netherlands in 1643, the Portuguese planters began a long campaign against his successors. This struggle against the Dutch was later considered formative for later Brazilian independence. Newly independent, Portugal finally agreed to pay the Netherlands 4 million reais (63 metric tons of gold) for abandoning its claims to the territory.

Chile

In 1643 a Dutch fleet sailed from Dutch Brazil to Southern Chile with the goal of establishing a base in the ruins of the abandoned Spanish city of Valdivia. The expedition led by Hendrik Brouwer sacked the Spanish Fort at Carelmapu and the settlement of Castro in Chiloé Archipelago before sailing to Valdivia. The Dutch arrived to Valdivia on 24 August 1643, built a fort and named the colony Brouwershaven after Brouwer who had died several weeks earlier. The short-lived colony was abandoned on 28 October 1643 as they did not find the gold mines they had expected. Nevertheless, the occupation caused great alarm among Spanish authorities and the Spanish resettled Valdivia and begun the construction of an extensive network of fortifications in 1645 to prevent any similar intrusions from happening again. Although contemporaries considered the possibility of a new incursion, the expedition was the last one undertaken by the Dutch on the west coast of the Americas.[34][35]

References

- ^ "Ship - History of ships". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Salomons, Bobby (2017-12-15). "The Dutch East India Company was richer than Apple, Google and Facebook combined". DutchReview. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Dutch West India Company | Dutch trading company". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Revolutionary War". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Bosma, Ulbe (2014). "The Economic Historiography of the Dutch Colonial Empire". Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis. 11 (2): 153. doi:10.18352/tseg.136.

- ^ "American Revolution". History. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "French Revolution". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ History.com. "Enlightenment". History.com. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Doel. "The Dutch Empire. An Essential Part of World History". Academia.edu. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Dutch East India Company, Dutch Trading Company". Britannica.com. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Australia's Bloodiest Shipwreck". www.nationalgeographic.com.au. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Saltwater Aquarium Fish for Marine Aquariums: Ambon Damselfish, Captive-Bred". m.liveaquaria.com. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Cooking with Nutmeg and Mace - including therapeutic benefits and recipes". www.helpwithcooking.com. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Israel, Jonathan (Spring 1997). "The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477–1806. Volume I, The Oxford History of Early Modern Europe". The Historians. 60 (2): 433–434.

- ^ Klooster, Wim (2016). The Dutch Moment War, Trade and settlement in the Seventeenth Century Atlantic World. Leiden University Press. pp. 33–187. ISBN 9780801450457.

- ^ Lloyd, T. H. (Terrence Henry), 1937- (1977). The English wool trade in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521212391. OCLC 2372597.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Material world | Flanders Today". www.flanderstoday.eu. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ a b c "The Dutch Economy in the Golden Age (16th – 17th Centuries)". eh.net. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ "South African War | Definition, Causes, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Boer War begins in South Africa". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "The German invasion of the Netherlands". Anne Frank Website. 2018-09-28. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Gommans, Jos (2015). Exploring the Dutch Empire Agents Networks and institution 1600-2000. London: London Bloomsbury Academia. pp. 77–130.

- ^ "Colonial Voyage - The website dedicated to the Colonial History". Colonial Voyage.

- ^ Junie T. Tong (2016). Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- ^ John L. Esposito, ed. (2004). The Islamic World: Past and Present. Vol. 1: Abba - Hist. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3.

- ^ Nanda, J. N (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. 2005. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- ^ Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- ^ Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ Hobkirk, Michael (1992). Land, Sea or Air?: Military Priorities- Historical Choices. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-0312074937.

- ^ "香港經歷四次殖民侵略". www.takungpao.com.hk/paper/2017/1110/125170.html. 大公網. 2017-11-10. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Peter Stuyvesant". www.newnetherlandinstitute.org. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Bosma, Ulbe (2014). "The Economic Historiography of the Dutch Colonial Empire". Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis. 11 (2): 153. doi:10.18352/tseg.136. ISSN 2468-9068.

- ^ van den Doel, Wim; Doel, Wim van den (2010). "The Dutch Empire. An Essential Part of World History". BMGN: Low Countries Historical Review. 125 (2–3): 179. doi:10.18352/bmgn-lchr.7119. ISSN 2211-2898.

- ^ "Breve Historia de Valdivia". Editorial Francisco de Aguirre. 1971. Archived from the original on 2007-02-18. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ Lane, Kris E. (1998). Pillageing the Empire: Piracy in the Americas 1500–1750. M.E. Sharpe. p. 90. ISBN 9780765630834.

An asterisk (*) designates a trading post

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !