Hiram Powers

Hiram Powers (July 29, 1805 – June 27, 1873) was an American neoclassical sculptor. He was one of the first 19th-century American artists to gain an international reputation, largely based on his famous marble sculpture The Greek Slave.

Early life and studies

Powers was born to a farmer on July 29, 1805 in Woodstock, Vermont.[1][2] When he was 14 years old, his family moved to Ohio, about six miles from Cincinnati, where Powers attended school for about a year[1] while staying with his father's brother, a lawyer. He began working after the death of his parents, first superintending a reading-room in connection with the chief hotel of the town, then working as a clerk in a general store.[3][4] At age 17, Powers became an assistant to Luman Watson, Cincinnati's early wooden clockmaker, who owned a clock and organ factory. Using his skill in modeling figures, Powers mastered the construction of the instruments and became the first mechanic in the factory.[1]

In 1826, he began to frequent the studio of Frederick Eckstein, and at once conceived a strong passion for the art of sculpture. His proficiency in modeling secured him the situation of general assistant and artist of the Western Museum, kept by a Louisiana naturalist of French extraction named Joseph Dorfeuille.[2] Here he created representations of scenes in the poem Inferno by Dante, which met with extraordinary success.[2] Fanny Trollope helped launch his career when she had him sculpt Dante's Commedia.[5] After studying thoroughly the art of modeling and casting, he moved to Washington, D.C. at the end of 1834.[2]

Career as a sculptor

Powers drew attention and local commissions in Washington, D.C. with his modeled portrait of Andrew Jackson.[2] In 1837 he moved to Italy and settled on the Via Fornace in Florence, where he had access to good supplies of marble and to traditions of stone-cutting and bronze casting. He remained in Florence till his death, though he did travel to Britain during this time. During his time in Italy, he developed a friendship with Horatio Greenough.[2] He developed a thriving business in portraiture and "fancy" parlor busts, but he also devoted his time to creating life-size, full-figure ideal subjects, many of which were also isolated as a bust. In 1839 his statue of Eve won the admiration of the leading European neoclassical sculptor, Bertel Thorvaldsen.[citation needed]

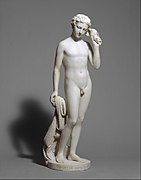

In 1843 Powers produced his most celebrated statue, The Greek Slave, which at once gave him a place among the leading sculptors of his time. It attracted more than 100,000 viewers when it toured America in 1847; and in 1851 was exhibited in Britain (along with the Fisher Boy, his other very famous statue, mentioned below) at the center of the Crystal Palace Exhibition, when Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote a sonnet on it.[2] This sculpture was used in the abolitionist cause and copies of it appeared in many Union-supporting state houses. Among the best known of his other idealising statues are The Fisher Boy, Il Penseroso, Eve Disconsolate, California, America and The Last of the Tribe (also called The Last of Her Tribe). He was elected an Associate Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1851.[6]

Powers' most discerning and important private client was Prince Anatole Demidoff, who owned marble full-figure versions of both the Greek Slave and the Fisher Boy and also commissioned from Powers a portrait bust of his wife, the niece of Napoleon and the Grand Duchess of Tuscany. The statues and busts Powers carved for Demidoff were exceptional in the quality and purity of the marble employed.[7]

Powers became a teacher at the Florence Accademia. One of his sons was the sculptor Preston Powers.

Hiram Powers died on June 27, 1873, and is buried, as were three of his children, at the Cimitero Protestante di Porta a' Pinti, Florence (English Cemetery, Florence).

Spiritual descendants of Hiram Powers in Europe included the notorious Futurist designer 'Thayaht,' pseudonym of Ernesto Michahelles and his brother, the notorious neo-metaphysical artist RAM, pseudonym of Ruggero Alfredo Michahelles who was awarded the "Prix Paul Guillaume" in Paris in 1937.

Collections

In 2007 the Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio presented the first major exhibition devoted to his work, "Hiram Powers: Genius in Marble". This is the same place of the first solo exhibition of Powers' work in Cincinnati in 1842, when Nicholas Longworth opened his private residence to allow the public to view Power's newest sculpture.[8]

Collections holding works by Hiram Powers include the Addison Gallery of American Art (Andover, Massachusetts), the Amon Carter Museum (Texas), the Arizona State University Art Museum, the Art Gallery of the University of Rochester (New York), the Art Institute of Chicago (Illinois), the Berkshire Museum (Massachusetts), the Birmingham Museum of Art (Alabama), the Brooklyn Museum of Art (New York City), the Carnegie Museum of Art (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), the Chrysler Museum of Art (Norfolk, Virginia), the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.), Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College (Florida), High Museum of Art (Atlanta, GA) Dallas Museum of Art (Texas), Detroit Institute of Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Glencairn Museum (Pennsylvania), the Greenville County Museum of Art (South Carolina), Harvard University Art Museums, the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Hudson River Museum (Yonkers, New York), the McMullen Museum of Art (Massachusetts), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Milwaukee Art Museum, Miami University, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA), the Morse Museum of American Art, (Florida), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston the National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.), the Newark Museum (New Jersey), the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Portland Museum of Art (Maine), Raby Castle (County Durham, England), the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington D.C.), the United States Senate Art Collection, the University of Cincinnati Galleries (Ohio), the University of Michigan Museum of Art, the Vermont State House Fine Arts Collection (Montpelier, Vermont), the White House Collection, (Washington), the Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, Connecticut), Huddersfield Art Gallery (UK) and Edward Lee McClain High School (Greenfield, Ohio).

Gallery

-

President Andrew Jackson, modeled in 1835

-

Proserpine, 1844

-

Benjamin Franklin, 1844–60

-

America, 1854

-

Fisher Boy, 1857

-

Hope, ca. 1866

-

The Last of the Tribes, 1876–77

References

- ^ a b c Malloy, Judy Powers. "Hiram Powers (1805-1873): Vermont-born Irish American Sculptor, who Lived and Worked in Florence, Italy".

- ^ a b c d e f g "Hiram Powers". Encyclopædia Britannica. July 7, 2013.

- ^ Lynne D. Ambrosini and Rebecca A. G. Reynolds (2007). Hiram Powers: Genius in Marble. Cincinnati: Taft Museum of Art.

- ^ "Hiram Powers". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ White, Edmund. "FRANCES TROLLOPE PORTAL". FLORIN WEBSITE.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter P" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ "Theresa Leininger-Miller reviews Hiram Powers: Genius in Marble". NCAW | Volume 17, Issue 2 | Autumn 2018. August 12, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ "2006-2008 Exhibitions". Taft Museum of Art. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

Further reading

- Tolles, Thayer. "Hiram Powers (1805–1873)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- David Wilson (2013). Hiram Powers' 'Demidoff' Fisher Boy, London. ISBN 978-0-9927224-0-1

- Lauren Lessing (2010). "Ties that Bind: Hiram Powers' Greek Slave and Nineteenth-century Marriage". American Art. 24 (Spring, 2010): 41–65.

- Lynne D. Ambrosini and Rebecca A. G. Reynolds (2007). Hiram Powers: Genius in Marble. Cincinnati: Taft Museum of Art.

- Russell E. Burke III (2000). Hiram Powers: The Last of the Tribes. New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries.

- Richard P. Wunder (1991). Hiram Powers: Vermont sculptor, 1805-1873. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-87413-310-6.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . . Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Art and the empire city: New York, 1825-1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Powers (see index)

- Artcyclopedia: list of sites featuring Powers' work

- 1805 births

- 1873 deaths

- 19th-century American sculptors

- 19th-century American male artists

- American male sculptors

- Neoclassical sculptors

- Vermont culture

- People from Woodstock, Vermont

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Artists from Vermont

- American expatriates in Italy

- Expatriates in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

- Sculptors from Ohio

- Artists of the Boston Public Library

- Sculptors from Vermont

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !