Hurricane John (1994)

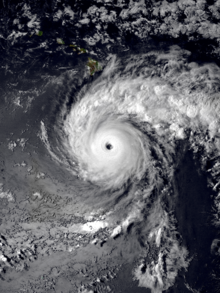

John near peak intensity to the south of Hawaii on August 23 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 11, 1994 |

| Extratropical | September 10, 1994 |

| Dissipated | September 13, 1994 |

| Duration | 4 weeks and 2 days |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 175 mph (280 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 929 mbar (hPa); 27.43 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | $15 million (1994 USD) |

| Areas affected | Hawaiian Islands, Johnston Atoll, Aleutian Islands, Alaska |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1994 Pacific hurricane and typhoon seasons | |

Hurricane John, also known as Typhoon John, was the farthest-traveling tropical cyclone ever observed worldwide. It was also the longest-lasting tropical cyclone on record globally at the time, until it was surpassed by Cyclone Freddy in 2023.[1] John formed during the 1994 Pacific hurricane season, which had above-average activity due to the El Niño of 1994–1995,[2] and peaked as a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale, the highest categorization for hurricanes.

Over the course of its existence, John followed a 13,180 km (8,190 mi) path from the eastern Pacific to the western Pacific and back to the central Pacific, lasting 31 days in total.[3][4][5] Because it existed in both the eastern and western Pacific, John was one of a small number of tropical cyclones to be designated as both a hurricane and a typhoon. Despite lasting for a full month, John barely affected land at all, bringing only minimal effects to the Hawaiian Islands and the United States military base on Johnston Atoll. Its remnants later affected Alaska.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Hurricane John were thought by the United States National Hurricane Center (NHC) to be from a tropical wave that moved off the coast of Africa on July 25, 1994.[6][7] The wave subsequently moved across the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean without distinction, before it crossed Central America and moved into the Eastern Pacific Ocean on or around August 8.[6][7] Upon entering the Eastern Pacific the wave gradually developed, before the NHC initiated advisories on the system and designated it as Tropical Depression Ten-E on August 11.[8] The system was at this time moving westwards and located around 345 miles (555 km) to the south-southeast of Acapulco, Mexico.[6][7] Quickly developing banding features and well-defined outflow, it was upgraded to a tropical storm and named John later that day.[3]

A strong ridge of high pressure over the northeastern Pacific Ocean forced John westward, where upper level wind shear kept John a tropical storm. Intensity fluctuated considerably, however, as shear levels varied. More than once, shear cleared away most of the clouds above John and nearly caused it to weaken to a tropical depression.[3] However, after eight days of slow westward movement across the Pacific Ocean, shear lessened greatly on August 19, and John intensified significantly and was designated as a hurricane at 17:00 PDT. During an eighteen-hour period between August 19 and 20, John further strengthened from a weak Category 1 hurricane to a Category 3 major hurricane. Around 1100 PDT on August 20, John crossed into the central Pacific, the first of three basin crosses John would make.[3]

After entering the central Pacific, John left the area monitored by the NHC and was instead monitored by the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC). As the storm moved slowly westward, Hurricane John continued to strengthen considerably in an increasingly favorable environment well south of the Hawaiian Islands; on August 22, John was designated a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale (the highest classification for hurricanes) and later that day (by Hawaii Standard Time) reached its peak intensity, with 1-minute sustained winds of 175 miles per hour (280 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 929 millibars (27.4 inHg).[9] Also, on August 22 (by Hawaii Standard Time), John made its closest approach to the Hawaiian Islands, 345 miles (555 km) to the south. John had threatened to turn north and affect the islands days before, but the ridge of high pressure that typically shields the islands from hurricanes kept John on its southerly path. Nonetheless, heavy rains and wind from the outer bands of John affected the islands.[9]

With the Hawaiian Islands behind it, John began a slow turn to the north, taking near-direct aim at Johnston Atoll, a small group of islands populated only by a United States military base. The storm slowly weakened from its peak as a Category 5 hurricane in the face of increasing shear, dropping down to a Category 1 hurricane with maximum winds of 90 mph (150 km/h). On August 25 local time, John made its closest approach to the Johnston Atoll only 15 miles (24 km) to the north. On Johnston Atoll, sustained winds were reported up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h), the equivalent of a strong tropical storm, and gusts up to 75 miles per hour (121 km/h) were recorded.[10]

Clearing Johnston Atoll, John turned to the northwest and began strengthening again as shear decreased. On August 27 local time, John reached a secondary peak strength of 130 mph (215 km/h), and shortly thereafter it crossed the International Date Line at approximately 22° N and came under the surveillance of the Guam branch of the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC). By crossing into the western Pacific, John also became a typhoon and was referred to as Typhoon John during its time in the western Pacific.[10] Immediately after crossing the Date Line, John again weakened and its forward motion stalled. By September 1, John had weakened to a tropical storm and was nearly motionless just west of the Date Line. There, John lingered for six days while performing a multi-day counterclockwise loop. On September 7, a trough moved into the area and quickly moved John to the northeast. John crossed the Date Line again on September 8 and reentered the central Pacific.[10]

After reentering the central Pacific, John briefly reached a tertiary peak strength of 90 mph (150 km/h), a strong Category 1 hurricane, well to the north of Midway Island. However, the trough was rapidly pulling apart John's structure, and the cold waters of the northern central Pacific were not conducive to a tropical cyclone. On September 10, the 120th advisory was released on the system, finally declaring John to have become extratropical approximately 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south of Unalaska Island.[10]

Records

John's 31-day existence made it the longest-lasting tropical cyclone recorded in the Pacific Ocean, surpassing Hurricane Tina's previous record of 24 days in the 1992 season, and the longest-lived globally on record, surpassing the San Ciriaco hurricane's duration of 28 days in the 1899 Atlantic season.[11] John's global record stood until 2023, when it was broken by Cyclone Freddy, which traversed the Indian Ocean in the Southern Hemisphere for 36 days.[1]

Additionally, despite its slow movement throughout much of its path, John was also the farthest-traveling tropical cyclone in both the Pacific Ocean and globally, with a distance traveled of 13,180 km (8,190 mi), only behind 2023's Cyclone Freddy, with a distance traveled of 12,785 km (7,945 mi), or about 33% of the Earth's circumference,[1] outdistancing the previous record of 7,600 kilometres (4,700 mi) set by Hurricane Fico in the 1978 season.[4] In addition, John was the first tropical cyclone on record to become a hurricane in the Eastern Pacific (east of 140°W), traverse the entire Central Pacific at hurricane strength, and then cross into the Western Pacific at the International Date Line (180°W) and become a typhoon, a feat matched only by Hurricane Dora in 2023.[12]

Pressure readings from John's peak are not consistently available as the CPHC did not monitor pressures at the time, but Air Force Reserve aircraft did measure a surface pressure of 929 mbar (hPa), making John one of the most intense hurricanes recorded in the central Pacific; both hurricanes Emilia and Gilma of 1994, as well as hurricanes Ioke of 2006 and Lane and Walaka of 2018 all recorded lower pressures in the central Pacific. However, all five had lower wind speeds than John. (Intensity is measured by minimum central pressure, which correlates with but is not directly linked to wind speeds.) John was also only the fourth Category 5 hurricane recorded in the central Pacific (the first was Hurricane Patsy in 1959, the second was Hurricane Emilia and the third one was Hurricane Gilma, both earlier in 1994). John also possessed the highest recorded wind speed in a central Pacific hurricane, 175 mph (280 km/h), a record shared with the aforementioned Patsy of 1959.[9] Since 1994, only three Category 5 hurricanes, Ioke in 2006, and hurricanes Lane and Walaka in 2018 have formed in or entered into the Central Pacific. Despite this however, John's pressure record is incomplete; the 929 millibars (27.43 inHg) reading was only measured when the winds were 160 mph (260 km/h); there is no pressure estimate for when it had winds of 175 mph (280 km/h), so it could have been more intense than Emilia, Gilma, Ioke, Lane, or Walaka.[13]

Impact

John affected both the Hawaiian Islands and Johnston Atoll, but only lightly. While John passed over 345 miles (555 km) to the south of Hawaii, the islands did experience strengthened trade winds and rough surf along the southeast- and south-facing shores, and, while moving westward, on west-facing shores as well.[10] The waves, ranging from 6 to 10 ft (1.8 to 3.0 m) in height, flooded beach parks in Kailua-Kona.[14] Additionally, heavy rains on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi caused minor, localized flooding and some short-term road closures. No deaths, injuries or significant damages were reported in Hawaiʻi.[10]

Although John passed within 25 km (16 mi) of Johnston Atoll, it had weakened greatly to a Category 1 system by closest approach.[10] Prior to the storm's arrival, waves between 20 and 30 ft (6.1 and 9.1 m) were reported on the island.[15] Additionally, in the Northern Hemisphere, the strongest winds and heaviest rain lie to the north of a tropical cyclone, so the atoll, which lay to the south of the storm's path, was spared the brunt of the storm. Nonetheless, the 1,100-man personnel for the United States military base on Johnston Atoll had been evacuated to Honolulu as a precaution while John approached. Damage to structures was considerable, but the size of the island and relative functionality of the base led to low damage; monetary losses were estimated at close to $15 million (1994 US$).[10]

The remnants of John moved through the Aleutian Islands, producing a wind gust of 46 mph (74 km/h) in Unalaska. The storm brought a plume of warm air, and two stations recorded a high temperature of 66 °F (19 °C).[16]

See also

- Other storms of the same name

- 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane – The longest-lived tropical cyclone recorded in the Atlantic Ocean

- Cyclone Leon–Eline (2000) – The second longest-lived tropical cyclone recorded in the Indian Ocean

- Cyclone Freddy (2023) – The longest-lived tropical cyclone recorded worldwide

Other powerful hurricanes that crossed the International Date Line:

- Hurricane Dora (1999)

- Hurricane Ioke (2006)

- Hurricane Genevieve (2014)

- Hurricane Hector (2018)

- Hurricane Dora (2023)

References

- ^ a b c "Tropical Cyclone Freddy is the longest tropical cyclone on record at 36 days: WMO". World Meteorological Organization. July 1, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Cold and Warm Episodes by Season". August 4, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Lawrence, Miles (1995). "Hurricane John Preliminary Report (page 1)". NOAA. Retrieved May 22, 2006.

- ^ a b Dorst, Neal (2004). "What is the farthest a tropical cyclone has traveled?". NOAA Tropical cyclone FAQ. NOAA. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2006.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone: Longest Distance Traveled by Tropical Cyclone". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, Miles B (January 3, 1995). Preliminary Report: Hurricane John: August 11 – September 10, 1994 (gif) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c Mayfield, Britt Max; Pasch, Richard J (1996). "Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Season of 1994". Monthly Weather Review. 124 (7). American Meteorological Society: 1585–1586. Bibcode:1996MWRv..124.1579P. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1996)124<1579:ENPHSO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles B (August 11, 1994). Tropical Depression Ten-E Discussion Number 1: August 11, 1994 09z (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, Miles (1995). "Hurricane John Preliminary Report (page 2)". NOAA. Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Central Pacific Hurricane Center (2004). "Hurricane John Preliminary Report" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved May 24, 2006. (Note that this report does not reflect changes made in post-season analysis.)

- ^ Dorst, Neal (2004). "Which tropical cyclone lasted the longest?". NOAA Tropical cyclone FAQ. NOAA. Archived from the original on September 24, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2006.

- ^ Barker, Aaron; Oberholtz, Chris (August 11, 2023). "Dora to become 2nd hurricane-strength storm to be in Eastern, Central and Western Pacific Ocean". FOX Weather. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ National Climatic Data Center (1994). "Event Report for Hawaii". Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2006.

- ^ Staff Writer (August 26, 1994). "Island braces for Hurricane John". Gainesville Sun. p. 4. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ "A Composite of Outstanding Storms" (PDF). Storm Data. 36 (9): 60. September 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

External links

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !