Jewish views on slavery

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Jewish views on slavery are varied both religiously and historically. Judaism's ancient and medieval religious texts contain numerous laws governing the ownership and treatment of slaves. Texts that contain such regulations include the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, the 12th-century Mishneh Torah by Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, also known as Maimonides, and the 16th-century Shulchan Aruch by Rabbi Yosef Karo.[1]

The Hebrew Bible contained two sets of laws, one for Canaanite slaves, and a more lenient set of laws for Hebrew slaves. From the time of the Pentateuch, the laws designated for Canaanites were applied to all non-Hebrew slaves. The Talmud's slavery laws, which were established in the second through the fifth centuries CE,[2] contain a single set of rules for all slaves, although there are a few exceptions where Hebrew slaves are treated differently from non-Hebrew slaves. The laws include punishment for slave owners that mistreat their slaves. In the modern era, when the abolitionist movement sought to outlaw slavery, some supporters of slavery used the laws to provide religious justification for the practice of slavery.

Broadly, the Biblical and Talmudic laws tended to consider slavery a form of contract between persons, theoretically reducible to voluntary slavery, unlike chattel slavery, where the enslaved person is legally rendered the personal property (chattel) of the slave owner. Hebrew slavery was prohibited during the Rabbinic era for as long as the Temple in Jerusalem is defunct (i.e., since 70 CE). Although not prohibited, Jewish ownership of non-Jewish slaves was constrained by Rabbinic authorities since non-Jewish slaves were to be offered conversion to Judaism during their first 12-months term as slaves. If accepted, the slaves were to become Jews, hence redeemed immediately. If rejected, the slaves were to be sold to non-Jewish owners. Accordingly, the Jewish law produced a constant stream of Jewish converts with previous slave experience. Additionally, Jews were required to redeem Jewish slaves from non-Jewish owners, making them a privileged enslavement item, albeit temporary. The combination has made Jews less likely to participate in enslavement and slave trade.

Historically, some Jewish people owned and traded slaves.[3] They participated in the medieval slave trade in Europe up to about the 12th century.[4][5] Several scholarly works have been published to rebut the antisemitic canard of Jewish domination of the slave trade in Africa and the Americas in the later centuries,[6][7][8] and to show that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery.[7][8][9][10] They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every Spanish territory in North America and the Caribbean, and "in no period did they play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades" (Wim Klooster quoted by Eli Faber).[11]

American mainland colonial Jews imported slaves from Africa at a rate proportionate to the general population. As slave sellers, their role was more marginal, although their involvement in the Brazilian and Caribbean trade is believed to be considerably more significant.[12] Jason H. Silverman, a historian of slavery, describes the part of Jews in slave trading in the southern United States as "minuscule", and writes that the historical rise and fall of slavery in the United States would not have been affected at all had there been no Jews living in the American South.[13] Jews accounted for 1.25% of all Southern slave owners, and were not significantly different from other slave owners in their treatment of slaves.[13]

The Exodus

The story of the Exodus from Egypt, as it is written in the Torah, has shaped the Jewish people throughout their history. Briefly outlined, the story recounts the experience of the Israelites under Egyptian enslavement, God's promise to redeem them from slavery, God's punishment of the Egyptians, and the Israelite redemption and departure from Egypt. The story of the Exodus has been interpreted and reinterpreted to suit or challenge cultural norms in every era and location.[14] The result over time has been a steady increase in the governance of masters in favor of slaves' rights and eventually the complete prohibition of slavery.[15][failed verification]

Biblical era

Ancient Israelite society allowed slavery; however, total domination of one human being by another was not permitted.[16][17] Rather, slavery in antiquity among the Israelites was closer to what would later be called indentured servitude.[15] In fact, there were cases in which, from a slave's point of view, the stability of servitude under a family in which the slave was well-treated would have been preferable to economic freedom.[18]

The Hebrew Bible contains two sets of rules governing slaves: one set for Hebrew slaves (Lev 25:39–43) and a second set for non-Hebrew slaves (Lev 25:45–46).[1][19] The main source of non-Hebrew slaves were prisoners of war,[20] while Hebrew slaves became slaves either because of extreme poverty (in which case they could sell themselves to an Israelite owner) or because of inability to pay a debt.[16] According to the Hebrew Bible, non-Hebrew slaves were drawn primarily from the neighboring nations (Lev 25:44).[21]

The laws governing non-Hebrew slaves were more harsh than those governing Hebrew slaves: non-Hebrew slaves could be owned permanently, and bequeathed to the owner's children,[22] whereas Hebrew slaves were treated as servants, and were released after six years of service or the occurrence of a jubilee year.[23][24] Despite this, the book of Deuteronomy required rest for non-Hebrew slaves on Shabbat[25] and their participation in Temple and holiday celebrations.[26] Participation in Passover, specifically, enabled them to become Israelite because foreign slaves were banned from celebrating Passover unless they circumcised, which made them equivalent to the native-born Israelite (Exodus 12:48).[27] Saul Olyan argued that non-Israelites automatically became Israelite if they lived in their territory (Ezekiel 47:21–23).[28]

In English translations of the Bible, the distinction is sometimes emphasized by translating the word ebed (עבד) as "slave" in the context of non-Hebrew slaves, and "servant" or "bondman" for Hebrew slaves.[29] Throughout the Hebrew Bible, ebed is also used to denote government officials who serve the king, sometimes high-ranking (for example, Nathan-melech, whose seal was discovered in archeological excavations). In translations of 2 Kings 23:11, Nathan-melech's title is translated as 'chamberlain,' 'officer' or 'official'.

Explanations for the differential treatment include all non-Hebrew slaves being subject to the curse of Canaan and God not wanting Hebrews to be enslaved again after freeing them from Egyptian enslavement.[30] Isaac S.D. Sassoon argued that it was the result of a bargain struck between commoners and landowners. Commoners protested the widespread practice of Israelites enslaving each other whilst landowners defended slavery as being indispensable to agriculture.[31] Rashi similarly proposed that it answered the question on who would serve the Israelite as a slave.[32]

Talmudic commentators likewise encouraged non-Hebrew slaves to convert to Judaism,[33][34][35] which helped them bypass the harsh treatment.[36]

The definition of non-Hebrew is debated among Jewish scholars. Ibn Ezra defines non-Hebrews as Gentiles who live close to Israel, such as Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites and Aramites.[37] Rashi excludes Canaanites from the definition since they were to be exterminated (Deuteronomy 20:16).[32]

It is impossible for scholars to quantify the number of slaves that were owned by ancient Israelites, or what percentage of households owned slaves, but it is possible to analyze social, legal, and economic impacts of slavery.[38] Most slaves owned by Israelites were non-Hebrew, and scholars are not certain what percentage of slaves were Hebrew: Ephraim Urbach, a distinguished scholar of Judaism, maintains that Israelites rarely owned Hebrew slaves after the Maccabean era, although it is certain that Israelites owned Hebrew slaves during the time of the Babylonian exile.[16] Another scholar suggests that Israelites continued to own Hebrew slaves through the Middle Ages, but that the Biblical rules were ignored, and Hebrew slaves were treated the same as non-Hebrews.[21]

The Torah forbids the return of runaway slaves who escape from their foreign land and their bondage and arrive in the Land of Israel. Furthermore, the Torah demands these runaway slaves be treated equally to any other resident alien.[39] This law is unique in the Ancient Near East.[40]

Talmudic era

In the early Common Era, the regulations concerning slave-ownership by Jews underwent an extensive expansion and codification within the Talmud.[which?][41] The precise issues that necessitated a clarification to the laws is still up for debate. The majority of current scholarly opinion holds that pressures to assimilate during the late Roman to early medieval period resulted in an attempt by Jewish communities to reinforce their own identities by drawing distinctions between their practices and the practices of non-Jews.[42][43] One author, however, has proposed that they could include factors such as ownership of non-Canaanite slaves, the continuing practice of owning Jewish slaves, or conflicts with Roman slave-ownership laws.[41] Thus, the Babylonian Talmud (redacted in 500 CE) contains an extensive set of laws governing slavery, which is more detailed than found in the Torah.

The major change found in the Talmud's slavery laws was that a single set of rules, with a few exceptions, governs both Jewish slaves and non-Jewish slaves.[21][44] Another change was that the distinction between Hebrew and non-Hebrew slaves began to diminish as the Talmud expanded during this period. This included an expanded set of obligations the owner incurred toward the slave as well as codifying the process for manumission (the freeing from slavery). It also included a large set of conditions, that allowed or required manumission to include requirements for education of slaves, expanding disability manumission, and in cases of religious conversion or necessity.[33][21][44][45][46][47] These restrictions were based on the Biblical injunction to treat slaves well with the reinforcement of the memory of Egyptian slavery which Jews were urged to remember by their scriptural texts.[48] However, historian Josephus wrote that the seven-year automatic release was still in effect if the slavery was a punishment for a crime the slave committed (as opposed to voluntary slavery due to poverty).[49] In addition, the notion of Canaanite slaves from the Jewish Bible is expanded to all non-Jewish slaves.[50]

Significant effort is given in the Talmud to address the property rights of slaves. While the Torah only refers to a slave's specific ability to collect gleanings, Talmudic sources interpret this commandment to include the right to own property more generally, and even "purchase" a portion of their own labor from the master. Hezser notes the often confusing mosaic of Talmudic laws distinguishes between finding property during work and earning property as a result of work.[51][52][53][54] While the Talmud affirmed that self-redemption of slaves (Jewish or not) was always permitted, it noted that conditionless manumission by the owner was generally a violation of legal precept.[55] The Talmud however, also included a varied list of circumstances and conditions that overrode this principle and mandated manumission. Conditions such as ill-treatment, oral promise, marriage to a free-woman, escape, inclusion in religious ceremony, and desire to visit the Holy Land all required the master to provide the slave with a deed of manumission, presented to him with witnesses. Failure to comply would result in excommunication.[55]

It is apparent that Jews still owned Jewish slaves in the Talmudic era because Talmudic authorities tried to denounce the practice[56] that Jews could sell themselves into slavery if they were poverty-stricken. In particular, the Talmud said that Jews should not sell themselves to non-Jews, and if they did, the Jewish community was urged to ransom or redeem the slave.[33]

While Jews did take slavery as a given, just as in other ancient societies, slaves in Jewish households could expect more compassionate treatment.[48]

Methods of acquisition

Acquisition of a non-Jewish slave by a Jew is expressly stated in the Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 3:1 [8a]) as being acquired in the following manner: A child who has been abandoned in the marketplace and who has been taken-up by a stranger, if his parents cannot be found, nor two witnesses who are able to claim that the child is the son of so-and-so, the child is then called an asūfī ("foundling") and may be handled as a slave by its patron, namely, the person who took him in. Even so, this is on the condition that the child is so small that he is unable to move about on his own volition, from one distant place to another distant place.[57] Had three years passed without objection, the child can be handled as his bona fide slave. In this case, the child is circumcised, immersed in a ritual bath, and obligated to keep the commandments as Jewish women.[58]

Maimonides rules that non-Jewish slaves may be acquired in three ways: by money, by contract, or by hazakah (usucaption). Hazakah of slaves can be performed by making use of them, just as one would do with slaves before their master. How? Had he unlaced his shoe, or shod him with a shoe, or had he carried his items [of clothing] to the bath house, or helped him to get undressed, or rubbed him down with [medicinal] oil, scratched [his back] for him, or helped him to get dressed, or had he lifted-up his master, in such [ways] he has acquired him [as a slave]. [...] Had he forcibly attacked him and brought him along with him, he has acquired thereby a slave, since slaves are acquired by having them drawn-along in such a manner. [...] A slave who is but a child is acquired by drawing him along, without the necessity of having to attack him."[59]

A Jewish slave is acquired differently, namely, when a Jewish court of law sells him into limited bondage (unto a Jewish master) for having engaged in thefts and not having that which to pay. In such cases, he does not work beyond six years. A Jewish bondmaid is sold by her father into servitude, usually because of severe poverty, but the girl's master, as a first resort, is required to betroth her in marriage after using her as his bondmaid. These sanctions only apply when the entire nation of Israel is settled in their own land and the laws of the Jubilee (Hebrew: יובל) have been re-instated.[60]

Curse of Ham as a justification for slavery

Some scholars have asserted that the Curse of Ham described in Judaism's religious texts was a justification for slavery[61]—citing the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) verses Genesis 9:20–27 and the Talmud.[62] Scholars such as David M. Goldenberg have analyzed the religious texts, and concluded that those conclusions on faulty interpretations of Rabbinical sources: Goldenberg concludes that the Judaic texts do not explicitly contain anti-black precepts, but instead later race-based interpretations were applied to the texts by later, non-Jewish analysts.[63]

While a slave of non-Jewish origin is known in Jewish law by the term "Canaanite slave", in fact this status applies to any person of non-Jewish origin held in bondage by an Israelite.[64][65] According to Jewish law, such a slave should undergo a form of conversion to Judaism, after which they are obligated to perform all mitzvot except positive time-dependent mitzvot (just as Jewish women do),[65] making him of a higher rank than ordinary gentiles when there is a question on whose life should be saved first.[66] Moreover, whenever a Canaanite slave is set free due to losing a limb[67] he becomes a free Israelite with the same status as any other Jew, including permission to marry a Jewish woman.[68][29] His emancipation must be followed by a written bill of manumission (sheṭar shiḥrūr) by the rabbinic court,[69] and must also be followed by a second immersion in a ritual bath.[70] Hence: a Canaanite slave's bondage was meant to elevate himself at a later juncture in life, although his Master in ordinary circumstances is under no constraints to set him free, unless he were physically and openly maimed.

According to Rashi and the Talmud, non-Jews are forbidden to own slaves, based on an exegesis of Leviticus 25:44.[71]

Female slaves

The classical rabbis instructed that masters could never marry female slaves. They would have to be manumitted first;[72] similarly, male slaves could not be allowed to marry Jewish women.[73] Unlike the biblical instruction to sell thieves into slavery (if they were caught during daylight and could not repay the theft), the rabbis ordered that female Israelites could never be sold into slavery for this reason.[29] Sexual relations between a slave owner and engaged slaves is prohibited in the Torah (Lev. 19:20–22).[74][75]

Freeing a slave

The Tanakh contains the rule that Jewish slaves would be released following six years of service, but that non-Jewish slaves could potentially be held indefinitely. However, their manumission was possible if they met certain criteria, which the Talmud codified and expanded.[76] Freeing a non-Jewish slave was seen as a religious conversion, and involved a second immersion in a ritual bath (mikveh). Jewish authorities of the Middle Ages argued against the Biblical rule that provided freedom for severely injured slaves.[77]

According to Maimonides, non-Jewish slaves could be freed if someone bribed the master to free the slave. However, if the briber gave the money to the slave, the master could reject the bribe. Alternatively, the master could sign a deed of manumission in the presence of two witnesses. If the slave wished to be treated as Hebrew slaves, they must pre-empt their master to undergo ritual immersion (mikveh) before the latter announces their status as a slave.[35]

They could be freed without their master's consent if:[35]

- If their master permanently disabled the slave in an 'apparent' way. This included knocking out their teeth, per Exodus 21:26.

- If their master sold them to a non-Jew.

- If the slave came from a foreign land and found refuge in Israel.

- If their master abandoned them.

- If the slave was treated in a way that is only appropriate for a free man. E.g. if marriage to a free woman is arranged, wearing tefillin, being asked to read Torah verses etc.

Treatment of slaves

The Torah and the Talmud contain various rules about how to treat slaves. Biblical rules for treatment of Jewish slaves were more lenient than for non-Jewish slaves[78][79][80] and the Talmud insisted that Jewish slaves should be granted similar food, drink, lodging, and bedding, to that which their master would grant to himself.[81] Laws existed that specified punishment of owners that killed slaves.[82][83] Jewish slaves were often treated as property; for example, they were not allowed to be counted towards the quorum, equal to 10 men, needed for public worship.[84] Maimonides and other halachic authorities forbade or strongly discouraged any unethical treatment of slaves, Jewish or not.[85][86] Some accounts indicate that Jewish slave-owners were affectionate, and would not sell slaves to a harsh master[87][obsolete source] and that Jewish slaves were treated as members of the slave-owner's family.[88]

Scholars are unsure to what extent the laws encouraging humane treatment were followed. In the 19th century, Jewish scholars such as Moses Mielziner and Samuel Krauss studied slave-ownership by ancient Jews, and generally concluded that Jewish slaves were treated as merely temporary bondsman, and that Jewish owners treated slaves with special compassion.[89] However, 20th century scholars such as Solomon Zeitlin and Ephraim Urbach, examined Jewish slave-ownership practices more critically, and their historical accounts generally conclude that Jews did own slaves at least through the Maccabean period, and that it was probably more ubiquitous and humane than earlier scholars had maintained.[90] Professor Catherine Hezser explains the differing conclusions by suggesting that the 19th century scholars were "emphasizing the humanitarian aspects and moral values of ancient Judaism, Mielziner, Grunfeld, Farbstein, and Krauss [to argue] that the Jewish tradition was not inferior to early Christian teachings on slaves and slavery."[89] David M. Cobin observes that biblical and rabbinic prohibitions against manumission were not vigorously enforced in practice. He cites Maimonides's rulings and legal practices conducted by Jewish communities during the 5th-2nd century BCE, as examples. Jews were also more likely to hold slaves if they lived in a society that tolerated slavery.[35]

Converting or circumcising non-Jewish slaves

The Talmudic laws required Jewish slave owners to try to convert non-Jewish slaves to Judaism.[33][34] Other laws required slaves, if not converted, to be circumcised and undergo mikveh.[34][91] A 4th century Roman law prevented the circumcision of non-Jewish slaves, so the practice may have declined at that time,[92] but increased again after the 10th century.[93][obsolete source] Jewish slave owners were not permitted to drink wine that had been touched by an uncircumcised person so there was always a practical need, in addition to the legal requirement, to circumcise slaves.[93]

Although conversion to Judaism was a possibility for slaves, rabbinic authorities Maimonides and Karo discouraged it on the basis that Jews were not permitted (in their time) to proselytize;[29] slaveowners could enter into special contracts by which they agree not to convert their slaves.[29] Furthermore, to convert a slave into Judaism without the owner's permission was seen as causing harm to the owner, on the basis that it would rob the owner of the slave's ability to work during the Sabbath, and it would prevent them from selling the slave to non-Jews.[29] Arguments for conversion include non-Jewish slaves having the tendency to spread compromising information to enemy nations. However, rabbis debate on whether they should be treated as native-born Jewish slaves after conversion.[35]

One exceptional issue, codified by Maimonides, was the requirement allocating a 12-month period when a Jewish owner of non-Jewish would propose conversion to the slave. If accepted, the slave would transition from being a Canaanite to a Hebrew, triggering a set of rights associated with the latter, including an early release. As noted above, Maimonides did not see Hebrew slavery as being permissible until Israel is reestablished with full religious rigor. Consequently, the release of a slave was to be immediate upon conversion. If unaccepted, the Jewish slave owner was required to sell the slave to non-Jews by the end of the 12-month period (Mishneh Torah, Sefer Kinyan 5:8:14). Prior to enslavement, if the non-Jewish individual decides to become a permanent slave by refusing to convert, the 12-month period does not apply. Instead, the slave might elect to convert at any time, with the consequences described (Ibid). It is unclear to what extent Maimonides's prescription was actually followed, but some scholars believe it played a role in the formation of Ashkenazi Jews, partially formed from converted slaves freed according to Maimonides' procedure.[36] Applications of this protocol were also proposed concerning the early formation of communities of African-American Jews.

The Maharashdam states that converted non-Jewish slaves should be freed even if they lack official evidence for conversion. Living a moral life was sufficient because "heathen slaves do not behave in this way".[35]

Post-Talmud to 1800s

Jewish slaves and masters

The role of Jewish merchants in the early medieval slave trade has been subject to much misinterpretation and distortion. Although medieval records demonstrate that there were Jews who owned slaves in medieval Europe, Toch (2013) notes that the claim repeated in older sources, such as those by Charles Verlinden, that Jewish merchants where the primary dealers in European slaves is based on misreadings of primary documents from that era. Contemporary Jewish sources do not attest any a large-scale slave trade or ownership of slaves which may be distinguished from the wider phenomenon of early medieval European slavery. The trope of the Jewish dealer of Christian slaves was additionally a prominent image in medieval European anti-Semitic propaganda.[94]

Halachic developments

Treatment of slaves

Jewish laws governing treatment of slaves were restated in the 12th century by noted rabbi Maimonides in his book Mishneh Torah, and again in the 16th century by Rabbi Yosef Karo in his book Shulchan Aruch.[95]

The legal prohibition against Jews owning Jewish slaves was emphasized in the Middle Ages[96] yet Jews continued to own Jewish slaves, and owners were able to bequeath Jewish slaves to the owner's children, but Jewish slaves were treated in many ways like members of the owner's family.[97][obsolete source]

Redeeming Jewish slaves

The Hebrew Bible contains instructions to redeem (purchase the freedom of) Jewish slaves owned by non-Jews (Lev. 25:47–51). Following the suppression of the First Jewish–Roman War by the Roman army (66-70 CE), many Jews were taken to Rome as prisoners of war.[29][98][99] In response, the Talmud contained guidance to emancipate Jewish slaves, but cautioned the redeemer against paying excessive prices since that may encourage Roman captors to enslave more Jews.[100] Josephus, himself a former 1st century slave, remarks that the faithfulness of Jewish slaves was appreciated by their owners;[101] this may have been one of the main reasons for freeing them.[29]

In the Middle Ages, redeeming Jewish slaves gained importance and—up until the 19th century—Jewish congregations around the Mediterranean Sea formed societies dedicated to that purpose.[102][obsolete source] Jewish communities customarily ransomed Jewish captives according to a Judaic mitzvah regarding the redemption of captives (Pidyon Shvuyim).[103] In his A History of the Jews, Paul Johnson wrote, "Jews were particularly valued as captives since it was believed, usually correctly, that even if they themselves poor, a Jewish community somewhere could be persuaded to ransom them. ... In Venice, the Jewish Levantine and Portuguese congregations set up a special organization for redeeming Jewish captives taken by Christians from Turkish ships, Jewish merchants paid a special tax on all goods to support it, which acted as a form of insurance since they were likely victims."[104]

Modern era

Latin America and the Caribbean

Jews participated in the European colonization of the Americas, owning and trading black slaves in Latin America and the Caribbean, most notably in Brazil and Suriname, but also in Barbados and Jamaica.[105][106][107] In Suriname, Jews owned many large plantations.[108] This included an area known as “Jodensavanne” (Jewish Savannah), where roughly 40 sugarcane plantations housed a Jewish community numbering several hundred and up to 9000 slaves, until its destruction during an 1832 slave revolt.[14][18]

Jewish participation in the trans-Atlantic slave trade was particularly pronounced in Dutch colonies, where “Jews can be said to have had tangible significance”, at one point controlling as much as 17% of Dutch Caribbean trade, according to historian Seymour Drescher.[24][26] Professor of Judaic Studies, Marc Lee Raphael, has stated “[the] economic life of the Jewish community of Curaçao revolved around ownership of sugar plantations and the marketing of sugar, the importing of manufactured goods, and heavy involvement in the slave trade, within a decade of their arrival, Jews owned 80 percent of the Curaçao plantations”.[22] This influence was significant enough that slave auctions scheduled on Jewish holidays would often be postponed.[109]

Mediterranean slave trade

The Jews of Algiers were frequent purchasers of Christian slaves from Barbary corsairs.[110] Meanwhile, Jewish brokers in Livorno, Italy, were instrumental in arranging the ransom of Christian slaves from Algiers to their home countries and freedom. Although one slave accused Livorno's Jewish brokers of holding the ransom until the captives died, this allegation is uncorroborated, and other reports indicate Jews as being very active in assisting the release of English Christian captives.[111] In 1637, an exceptionally poor year for ransoming captives, the few slaves freed were ransomed largely by Jewish factors in Algiers working with Henry Draper.[112]

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade transferred African slaves from Africa to colonies in the New World. Much of the slave trade followed a triangular route: slaves were transported from Africa to the Caribbean, sugar from there to North America or Europe, and manufactured goods from there to Africa. Jews and descendants of Jews participated in the slave trade on both sides of the Atlantic, in the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal on the eastern side, and in Brazil, Caribbean, and North America on the west side.[113]

After Spain and Portugal expelled many of their Jewish residents in the 1490s, many Jews from Spain and Portugal migrated to the Americas and to the Netherlands.[114] Jewish participation in the Atlantic slave trade increased through the 17th century because Spain and Portugal maintained a dominant role in the Atlantic trade and peaked in the early 18th century, but started to decline after the British "emerged with the asiento [permission to sell slaves in Spanish possessions] at the Peace of Utrecht in 1713", and Spain and Portugal soon became superseded by Northern European merchants in participation in the slave trade.[115] By the height of the Atlantic slave trade in the 18th century (spurred on in part due to increasing European demands for sugar), Jewish participation was minimised as the Northern European nations which held colonies in the Americas often refused to allow Jews among their number. Despite this, some Jewish immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies owned slaves on plantations in the Southern colonies.[114]

Brazil

The role of Jewish converts to Christianity (New Christians) and of Jewish traders was momentarily significant in Brazil[116] and the Christian inhabitants of Brazil were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco, and some Jews were among the leading slave traders in the colony.[117][obsolete source] Some Jews from Brazil migrated to Rhode Island in the American colonies, and played a significant but non dominant role in the 18th-century slave trade of that colony; this sector accounted for only a very tiny portion of the total human exports from Africa.[118]

Caribbean and Suriname

The New World location where Jews played the largest role in the slave-trade was in the Caribbean and Suriname, most notably in possessions of the Netherlands, that were serviced by the Dutch West India Company.[116] The slave trade was one of the most important occupations of Jews living in Suriname and the Caribbean.[119] The Jews of Suriname were the largest slave-holders in the region.[120]

According to Austen, "the only places where Jews came close to dominating the New World plantation systems were Curaçao and Suriname."[121] Slave auctions in the Dutch colonies were postponed if they fell on a Jewish holiday.[122] Jewish merchants in the Dutch colonies acted as middlemen, buying slaves from the Dutch West India Company, and reselling them to plantation owners.[123] The majority of buyers at slave auctions in the Brazil and the Dutch colonies were Jews.[124] Jews allegedly played a "major role" in the slave trade in Barbados[122][125] and Jamaica,[122] and Jewish plantation owners in Suriname helped suppress several slave revolts between 1690 and 1722.[120]

In Curaçao, Jews were involved in trading slaves, although at a far lesser extent compared to the Protestants of the island.[126] Jews imported fewer than 1,000 slaves to Curaçao between 1686 and 1710, after which the slave trade diminished.[122][127] Between 1630 and 1770, Jewish merchants settled or handled "at least 15,000 slaves" who landed in Curaçao, about one-sixth of the total Dutch slave trade.[128][129]

North American colonies

The Jewish role in the American slave trade was minimal.[130] According to historian and rabbi Bertram Korn, there were Jewish owners of plantations, but altogether they constituted only a tiny proportion of the industry.[131] In 1830 there were only four Jews among the 11,000 Southerners who owned fifty or more slaves.[132]

Of all the shipping ports in Colonial America, only in Newport, Rhode Island, did Jewish merchants play a significant part in the slave trade.[133]

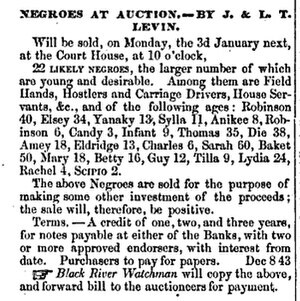

A table of the commissions of brokers in Charleston, South Carolina, shows that one Jewish brokerage accounted for 4% of the commissions. According to Bertram Korn, Jews accounted for 4 of the 44 slave-brokers in Charleston, three of 70 in Richmond, and 1 of 12 in Memphis.[134] However the proportion of Jewish residents of Charleston who owned slaves was similar to that of the general white population (83% versus 87% in 1830).[135]

Assessing the extent of Jewish involvement in the Atlantic slave trade

Historian Seymour Drescher emphasized the problems of determining whether or not slave-traders were Jewish. He concludes that New Christian merchants managed to gain control of a sizeable share of all segments of the Portuguese Atlantic slave trade during the Iberian-dominated phase of the Atlantic system. Due to forcible conversions of Jews to Christianity many New Christians continued to practice Judaism in secret, meaning it is impossible for historians to determine what portion of these slave traders were Jewish, because to do so would require the historian to choose one of several definitions of "Jewish".[138][139]

The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews (book)

In 1991, the Nation of Islam (NOI) published The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, which alleged that Jews had dominated the Atlantic slave trade.[140] Volume 1 of the book claims Jews played a major role in the Atlantic slave trade, and profited from slavery.[141] The book was heavily criticized for being antisemitic, and for failing to provide any objective analysis of the role of Jews in the slave trade. Common criticisms included the book's selective quotations, "crude use of statistics",[114] and was purposefully trying to exaggerate the role of Jews.[142] The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) criticized the NOI and the book.[10] Henry Louis Gates Jr. criticized the book's intention and scholarship.[143]

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Historian Ralph A. Austen heavily criticized the book and said that although the book may seem fairly accurate, it is an antisemitic book. However, he added that before the publication of The Secret Relationship, some scholars were reluctant to discuss Jewish involvement in slavery because of fear of damaging the "shared liberal agenda" of Jews and African Americans.[144] In that sense, Austen found the book's aims of challenging the myth of universal Jewish benevolence throughout history to be legitimate even though the means to that end resulted in an antisemitic book.[145]

Later assessments

The publication of The Secret Relationship spurred detailed research into the participation of Jews in the Atlantic slave trade, resulting in the publication of the following works, most of which were published specifically to refute the thesis of The Secret Relationship:

- 1992 – Harold Brackman, Jew on the brain: A public refutation of the Nation of Islam's The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews

- 1992 – David Brion Davis, "Jews in the Slave Trade", in Culturefront (Fall 1 992), pp. 42–45

- 1993 – Seymour Drescher, "The Role of Jews in the Atlantic Slave Trade", Immigrants and Minorities, 12 (1993), pp. 113–25

- 1993 – Marc Caplan, Jew-Hatred As History: An Analysis of the Nation of Islam's "The Secret Relationship" (published by the Anti Defamation League)

- 1998 – Eli Faber, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight, New York University Press

- 1999 – Saul S. Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade, Transaction

Most post-1991 scholars that analysed the role of Jews only identified certain regions (such as Brazil and the Caribbean) where the participation was "significant".[146] Wim Klooster wrote: "In no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades. They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every British territory in North America and the Caribbean. Even when Jews in a handful of places owned slaves in proportions slightly above their representation among a town's families, such cases do not come close to corroborating the assertions of The Secret Relationship".[11]

David Brion Davis wrote that "Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery."[147] Jacob R. Marcus wrote that Jewish participation in the American Colonies was "minimal" and inconsistent.[148] Bertram Korn wrote "all of the Jewish slavetraders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South."[149]

According to a review in The Journal of American History of both Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight and Jews and the American Slave Trade: "Faber acknowledges the few merchants of Jewish background locally prominent in slaving during the second half of the eighteenth century but otherwise confirms the small-to-minuscule size of colonial Jewish communities of any sort and shows them engaged in slaving and slave holding only to degrees indistinguishable from those of their English competitors."[150]

According to Seymour Drescher, Jews participated in the Atlantic slave trade, particularly in Brazil and Suriname,[151] however "in no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades" (Wim Klooster).[11] He said that Jews rarely established new slave-trading routes, but rather worked in conjunction with a Christian partner, on trade routes that had been established by Christians and endorsed by Christian leaders of nations.[152][153] In 1995 the American Historical Association (AHA) issued a statement, together with Drescher, condemning "any statement alleging that Jews played a disproportionate role in the Atlantic slave trade".[154]

According to a review in The Journal of American History of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight (Faber) and Jews and the American Slave Trade (Friedman), "Eli Faber takes a quantitative approach to Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade in Britain's Atlantic empire, starting with the arrival of Sephardic Jews in the London resettlement of the 1650s, calculating their participation in the trading companies of the late seventeenth century, and then using a solid range of standard quantitative sources (Naval Office shipping lists, censuses, tax records, and so on) to assess the prominence in slaving and slave owning of merchants and planters identifiable as Jewish in Barbados, Jamaica, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston, and all other smaller English colonial ports."[155] Historian Ralph Austen, however, acknowledges "Sephardi Jews in the New World had been heavily involved in the African slave trade."[156]

Jewish slave ownership in the southern United States

Slavery historian Jason H. Silverman describes the part of Jews in slave trading in the southern United states as "minuscule", and wrote that the historical rise and fall of slavery in the United States would not have been affected at all had there been no Jews living in the south.[13] Jews accounted for only 1.25% of all Southern slave owners.[13]

Jewish slave ownership practices in the Southern United States were governed by regional practices, rather than Judaic law.[13][157][158] Jews conformed to the prevailing patterns of slave ownership in the South, and were not significantly different from other slave owners in their treatment of slaves.[13] Wealthy Jewish families in the American South generally preferred employing white servants rather than owning slaves.[158] Jewish slave owners included Aaron Lopez, Francis Salvador, Judah Touro, and Haym Salomon.[159]

Jewish slave owners were found mostly in business or domestic settings, rather than on plantations, so most of the slave ownership was in an urban context—running a business or as domestic servants.[157][158] Jewish slave owners freed their black slaves at about the same rate as non-Jewish slave owners.[13] Jewish slave owners sometimes bequeathed slaves to their children in their wills.[13]

Abolition debate

A significant number of Jews gave their energies to the antislavery movement.[160] Many 19th century Jews, such as Adolphe Crémieux, participated in the moral outcry against slavery.[161] In 1849, Crémieux announced the abolition of slavery throughout the French possessions.[162]

In Britain, there were Jewish members of the abolition groups. Granville Sharp and Wilberforce, in his "A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade", employed Jewish teachings as arguments against slavery. Rabbi G. Gottheil of Manchester, and Dr. L. Philippson of Bonn and Magdeburg, forcibly combated the view announced by Southern sympathizers that Judaism supports slavery. Rabbi M. Mielziner's anti-slavery work "Die Verhältnisse der Sklaverei bei den Alten Hebräern", published in 1859, was translated and published in the United States as "Slavery Among Hebrews".[162] Similarly, in Germany, Berthold Auerbach in his fictional work "Das Landhaus am Rhein" aroused public opinion against slavery and the slave trade, and Heinrich Heine also spoke against slavery.[162] Immigrant Jews were among abolitionist John Brown's band of antislavery fighters in Kansas, including Theodore Wiener (from Poland); Jacob Benjamin (from Bohemia), and August Bondi (1833–1907) from Vienna.[163][164] Nathan Meyer Rothschild was known for his role in the British abolition of the slave trade through his partial financing of the £20 million British government compensation paid to former owners of the freed slaves.[165]

A Jewish woman, Ernestine Rose, was called "queen of the platforms" in the 19th century because of her speeches in favor of abolition.[166] Her lectures were met with controversy. Her most ill-received appearance was likely in Charleston, Virginia (today West Virginia), where her lecture on the evils of slavery was met with such vehement opposition and outrage that she was forced to exercise considerable influence to even get out of the city safely.[167]

Pro-slavery Jews

See also: Military history of Jewish Americans § Civil War and Confederate Jews (category)

In the Civil War era, prominent Jewish religious leaders in the United States engaged in public debates about slavery.[168][169]: 13–34 Generally, rabbis from the Southern states supported slavery, and those from the North opposed slavery.[170]

However, in 1861, the Charlotte Evening Bulletin noted: "It is a singular fact that the most masterly expositions which have lately been made of the constitutional and the religious argument for slavery are from gentlemen of the Hebrew faith". After referring to the speech of Judah Benjamin, the "most unanswerable speech on the rights of the South ever made in the Senate", it refers to the lecture of Rabbi Raphall, "a discourse which stands like the tallest peak of the Himmalohs [sic]—immovable and incomparable".[171]

The most notable debate[172] was between Rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall, who defended slavery as it was practiced in the South because slavery was endorsed by the Bible, and rabbi David Einhorn, who opposed its current form.[173] However, there were not many Jews in the South, and Jews accounted for only 1.25% of all Southern slave owners.[13] In 1861, Raphall published his views in a treatise called "The Bible View of Slavery".[174] Raphall and other pro-slavery rabbis such as Isaac Leeser and J. M. Michelbacher (both of Virginia), used the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) to support their arguments.[175]

Abolitionist rabbis, including Einhorn and Michael Heilprin, concerned that Raphall's position would be seen as the official policy of American Judaism, vigorously rebutted his arguments, and argued that slavery—as practiced in the South—was immoral and not endorsed by Judaism.[176]

Ken Yellis, writing in The Forward, has suggested that "the majority of American Jews were mute on the subject, perhaps because they dreaded its tremendous corrosive power. Prior to 1861, there are virtually no instances of rabbinical sermons on slavery, probably due to fear that the controversy would trigger a sectional conflict in which Jewish families would be arrayed on opposite sides. ... America's largest Jewish community, New York's Jews, were overwhelmingly pro-southern, pro-slavery, and anti-Lincoln in the early years of the war." However, as the war progressed, "and the North's military victories mounted, feelings began to shift toward[s] ... the Union and eventually, emancipation."[177]

Contemporary times

Jews and African-Americans cooperated during the Civil Rights Movement, motivated partially by the common background of slavery, particularly the story of the Jewish enslavement in Egypt, as told in the Biblical story of the Book of Exodus, which many blacks identified with.[178] Seymour Siegel suggests that the historic struggle against prejudice faced by Jews led to a natural sympathy for any people confronting discrimination. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, spoke from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, where he emphasized how Jews identify deeply with African American disenfranchisement "born of our own painful historic experience", including slavery and ghettoization.[179][180]

Slavery (as defined as the total subjugation of one human being over another) is absolutely unacceptable in modern Judaism.[181][182][183]

See also

- The Bible and slavery

- The Bible and violence

- Christianity and slavery

- Christianity and violence

- Louis Farrakhan

- History of Christian thought on persecution and tolerance

- History of concubinage in the Muslim world

- History of slavery

- History of slavery in the Muslim world

- Islam and violence

- Islamic views on slavery

- Judaism and violence

- Aaron Lopez

- Mormonism and slavery

- Mormonism and violence

- Pidyon Shvuyim

- Racism in Israel

- Racism in Jewish communities

- Racism in Muslim communities

- Slavery and religion

- Slavery in 21st-century jihadism

- Slavery in ancient Egypt

- Slavery in ancient Greece

- Slavery in ancient Rome

- Slavery in antiquity

- Slavery in Brazil

- Slavery in colonial Spanish America

- Slavery in contemporary Africa

- Slavery in medieval Europe

- Malik Zulu Shabazz

- Slavery in the United States

- Slavery in the 21st century

- Xenophobia and racism in the Middle East

References

Notes

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 619

- ^ "The Talmud". BBC Religion. BBC. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Oscar Reiss (2 January 2004). The Jews in Colonial America. McFarland. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7864-1730-8.

- ^ Drescher, p. 107

- ^ "YIVO | Trade". www.yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ^ Saul Friedman. Jews and the American Slave Trade. pp. 250–254.

- ^ a b Reviewed Work: Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber by Paul Finkelman. Journal of Law and Religion, Vol 17, No 1/2 (2002), pp. 125-28[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Refutations of charges of Jewish prominence in slave trade:

- "Nor were Jews prominent in the slave trade. Of the 40 slave merchants in South Carolina, only 1 minor trader was a Jew." [paragraph goes on to list similar breakdowns for other US states] – Marvin Perry, Frederick M. Schweitzer: Antisemitism: Myth and Hate from Antiquity to the Present, p. 245. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002; ISBN 0-312-16561-7

- "In no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades. They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every British territory in North America and the Caribbean. Even when Jews in a handful of places owned slaves in proportions slightly above their representation among a town's families, such cases do not come close to corroborating the assertions of The Secret Relationship." – Wim Klooster (University of Southern Maine): Review of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber[permanent dead link] (2000). "Reappraisals in Jewish Social and Intellectual History", William and Mary Quarterly Review of Books. Volume LVII, Number 1. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture[ISBN missing]

- "Medieval Christians greatly exaggerated the supposed Jewish control over trade and finance and also became obsessed with alleged Jewish plots to enslave, convert, or sell non-Jews... Most European Jews lived in poor communities on the margins of Christian society; they continued to suffer most of the legal disabilities associated with slavery. ... Whatever Jewish refugees from Brazil may have contributed to the northwestward expansion of sugar and slaves, it is clear that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery." – Professor David Brion Davis of Yale University in Slavery and Human Progress (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 89 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine)

- "The Jews of Newport seem not to have pursued the [slave trading] business consistently ... [When] we compare the number of vessels employed in the traffic by all merchants with the number sent to the African coast by Jewish traders ... we can see that the Jewish participation was minimal. It may be safely assumed that over a period of years American Jewish businessmen were accountable for considerably less than two percent of the slave imports into the West Indies" – Professor Jacob R. Marcus of Hebrew Union College in The Colonial American Jew (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970), Vol. 2, pp. 702-703 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine )

- "None of the major slave-traders was Jewish, nor did Jews constitute a large proportion in any particular community. ... probably all of the Jewish slave-traders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South." – Bertram W. Korn, Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865, in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol 3, pp. 197-198 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine )

- "[There were] Jewish owners of plantations, but altogether they constituted only a tiny proportion of the Southerners whose habits, opinions, and status were to become decisive for the entire section, and eventually for the entire country. ... [Only one Jew] tried his hand as a plantation overseer even if only for a brief time." – Bertram W. Korn, "Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865", The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol 3, p. 180 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine )

- ^ Davis, David Brion (1984). Slavery and Human Progress. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 89. Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ a b Anti-Semitism. Farrakhan In His Own Words. On Jewish Involvement in the Slave Trade Archived 2007-09-21 at the Wayback Machine and Nation of Islam. Jew-Hatred as History Archived 2007-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. adl.org (December 31, 2001).

- ^ a b c Herbert Klein (Journal of Social History): Review of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber. "Journal of Social History" 33.3 (2000) 743-745

- ^ The Columbia History of Jews and Judaism in America, p. 43, by Rabbi Marc Lee Raphael, (Columbia University Press, February 12, 2008); ISBN 978-0231132220. "During the 1990s, allegations that Jews financed, dominated, and controlled the slave trade captured wide attention and were widely accepted in the African American community (on the latter point, see Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s "Black Demagogues and Pseudo-Scholars", New York Times, July 20, 1992, p. A15). Subsequent extensive research demonstrated this was not the case, see David Brion Davis, "Jews in the Slave Trade", Culturefront (Fall 1992): 42-45

* Seymour Drescher, "The Role of Jews in the Transatlantic Slave Trade", Immigrants and Minorities 12 (1993): 113-25

Eli Faber, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight (New York, 1998)

Saul S. Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade (New Brunswick, NJ, 1998).

For numerical data demonstrating the minute role played by mainland colonial Jews in the importation of slaves from Africa and the Caribbean and their marginal role as slave sellers, see Faber, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade, pp. 131-42"; retrieved from Google Books on January 28, 2013. - ^ a b c d e f g h i Rodriguez, p. 385

- ^ a b Kushner, 332.

- ^ a b Kushner, 457

- ^ a b c Hezser, p. 6

- ^ Potok, 457-459

- ^ a b Tigay, 153

- ^ Hezser, p. 29

- ^ Hezser, p. 382

- ^ a b c d Schorsch, p. 63

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:45-45

- ^ Hezser, p. 30

- ^ a b Potok, 457

- ^ Deuteronomy 5:12–15

- ^ a b Deuteronomy 12:18; 16:11,14

- ^ Lau, Peter H.W. (2009). "Gentile Incorporation into Israel in Ezra - Nehemiah?". Peeters Publishers. 90 (3): 356–373. JSTOR 42614919 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Olyan, Saul (2000). Rites and Rank: Hierarchy in Biblical Representations of Cult. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691029481.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. Slaves and Slavery

- ^ Hezser, pp. 10, 30

- ^ Sassoon, Isaac S.D. (2015). "Did Israel Celebrate Their Freedom While Owning Slaves?". TheTorah.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Rashi, Leviticus 25:44

- ^ a b c d Hastings, p. 620

- ^ a b c Lewis, p. 8-9

- ^ a b c d e f Cobin, David M. (1995). "A Brief Look at the Jewish Law of Manumission - Freedom: Beyond the United States". Chicago-Kent Law Review. 70 (3) – via Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law.

- ^ a b אסף, שמחה. "Slavery and the Slave-Trade among the Jews during the Middle Ages (from the Jewish sources)/עבדים וסחר-עבדים אצל היהודים בימי הבינים (עפ" י המקורות העבריים)." ציון (1939): 91-125.

- ^ Ibn Ezra, Leviticus 25:44

- ^ Hezser, p. 23

- ^ Deuteronomy 23:16–17

- ^ Potok, 1124-1125

- ^ a b Blackburn, p. 68

- ^ Urbach, pp. 3-4, 37-38

- ^ Milikowsky, Collected Writings in Jewish Studies

- ^ a b Hezser, pp. 8, 31-33, 39

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia, "Slaves and Slavery"

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, Slavery in Judaism

- ^ Kid 24a, Git 38b, Yev 93b

- ^ a b Martin Goodman (25 January 2007). Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations. Penguin Books Limited. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-14-190637-9.

- ^ Hezser, p. 33

- ^ Schorsch, pp. 64-65

- ^ Hezser, p. 46

- ^ Garnsey, "Ideas of Slavery from Aristotle to Augustine"

- ^ Schorsch

- ^ Kid 11b, Kid 14b (note 13), Ar. 1:2, Shek. 1:5, Pes. 8:2, 88b, Yev. 66a, Yev. 7:1, BK 11:1, BB 51b–52a, Sanh. 91a, 105a, Ket. 28a, Meg. 16a

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 620, citing Gitten 45b

- ^ Lev. 25:39

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 3:1 [8a]), Commentary Pnei Moshe, s.v. אבל בתינוק המרגיע

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 6. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. pp. 91 [46a], 93 [47a] (Hil. ʻAvadim 8:12, 8:20). OCLC 122758200.

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 6. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. pp. 6 [3b] – 7 [4a] (Hil. Mekhirah 2:1–4). OCLC 122758200.

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 6. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. p. 63 [32a] (Hil. ʻAvadim 1:10). OCLC 122758200.

- ^

- Shavit, Jacob (2001). History in Black: African-Americans in search of an ancient past. Routledge. pp. 183–185. ISBN 0-7146-5062-5.

- Blackburn, Robin (1998). The making of New World slavery: from the Baroque to the modern, 1492-1800. Verso. p. 89. ISBN 1-85984-195-3.

- Hannaford, Ivan (1996). Race: the history of an idea in the West. Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- Haynes, Stephen R. (2002). Noah's curse: the biblical justification of American slavery. Oxford University Press. pp. 23–27, 65–104. ISBN 978-0-19-514279-2.

- Whitford, David M. (2009). The Curse of Ham in the Early Modern Era: The Bible and the Justifications for Slavery. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 19–26.

- Washington, Joseph R. (1985) "Anti-Blackness in English religion", E. Mellen Press, p. 1, 10-11, quoted in The curse of Ham, David M. Goldenberg, 2003.

- Jordon, Winthrop D. (1968) "White over black: American attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812", University of North Carolina Press, p. 18, 10-11, quoted in The curse of Ham, David M. Goldenberg, 2003.

- ^ Talmud verse: "Three copulated on the ark and they were all punished ... Ham was smitten in his skin". Sanhedrin 108B, as quoted by Robin Blackburn in "The making of New World slavery: from the Baroque to the modern, 1492-1800 ", Verso 1998, p. 68,88-89

- ^

- Goldenberg, David M. (2003). The curse of Ham: race and slavery in early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton University Press.

- Goldenberg, David. "The curse of Ham: a case of Rabbinic racism?", in Struggles in the promised land: toward a history of Black-Jewish relations in the United States, (Jack Salzman, Ed), Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 21-52.

- Goldenberg (in his book and essay) identifies several sources that — in his opinion — improperly assert that Judaism may be partially responsible for slavery or racism, including:

- - Thomas Gosset: "Race: The History of an Idea in America" 1963, p. 5

- - Raphael Patai & Robert Graves: "Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis", p. 121.

- - J. A. Rogers "Sex and Race" (1940-1944) 3:316-317

- - J. A. Rogers "Nature Knows no Color-Line" (1952), p. 9-10.

- - Edith Sanders "The Hamitic Hypothesis" in "Journal of African History" vol 10, num 4 (1969), p. 521-532

- - Joseph Harris "Africans and their History" (1972), p. 14-15

- - Leslie Fiedler "Negro and Jew: Encounter in America" in "The collected essays of Lesley Feidler" 1971

- - Raoul Allier "Une Enigme troublante: la race et la maledictiou e Cham" 1930;, p. 16-19, 32

- - Winthrop Jordan "White over Black", p. 18 (1968)

- - Washington post (Sept 14, 1991;, p. B6)

- - Charles Copher "Blacks and Jews in HIstorical Interaction" in "The Journal of the Interdenominational Theological Center 3" (1975), p. 16.

- - Tony Martin "The Jewish Onslaught" (1993), p. 33.

- - Nation of Islam publication: "The Secret Relationship between Blacks and Jews" 1991;, p. 203

- - St. Claire Drake "Black Folk Here and There" vol 2 (1990), p. 17-30, 22-23

- - Joseph R. Washington "Anti-Blackness in English Religion" 1984, p. 1, 10-11

- ^ Leviticus 25:44–46

- ^ a b "אנציקלופדיה יהודית דעת - עבד כנעני ;". www.daat.ac.il.

- ^ Mishnah (Horayiot 3:8); cf. Babylonian Talmud (Horayiot 13a), which puts an emancipated Canaanite slave before an ordinary convert, since he had been raised in holiness, whereas the other one had not.

- ^ As required by Exodus 21:26 in the case of losing a tooth or eye, and understood by the rabbis to apply if any of the 24 irreplaceable chief limbs in a man's body is lost

- ^ Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Issurei Bi'ah 12:17; 13:12–13)

- ^ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Avadim 5:4-ff.

- ^ Maimonides, Mishne Torah, Issurei Bi'ah 13:12–13

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Gittin 38a; Rashi to Kiddushin 6b, s.v. וצריך גט שחרור

- ^ Gittin, 40a

- ^ Gittin 4:5

- ^ Abrahams, p. 95

- ^ Roth, p. 61

- ^ See Gittin 1:4, 1:6, and 40b.

- ^ The Bible said a slave should be freed if they had been harmed to the extent that their injury was covered by the lex talionis – Exodus 21:26–27, should actually apply only to slaves who had converted to Judaism; additionally, Maimonides argued that manumission was really punishment of the owner and so that it could only be imposed by a court and required evidence from witnesses. —Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Leviticus 25:43

- ^ Leviticus 25:53

- ^ Leviticus 25:39

- ^ Furthermore, the Talmud instructed that servants were not to be unreasonably penalised for being absent from work due to sickness. The biblical seventh-year manumission was still to occur after the slave had been enslaved for six years; extra enslavement could not be tacked on to make up for the absence, unless the slave had been absent for more than a total of four years, and if the illness did not prevent light work (such as needlework), the slave could be ill for all six years without having to repay the time.

- ^ The vague ("Avenger of Blood", Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901.) biblical instruction to avenge slaves that had died, from punishment by their masters, Exodus 21:20–21 became regarded as an instruction to view such events as murder, with masters guilty of such crime being beheaded, see Mekhilta, Mishpatim 7

- ^ On the other hand, the protection given to fugitive slaves was lessened by the classical rabbis; fugitive Israelite slaves were now compelled to buy their freedom, and if they were recaptured, then the time they had been absent was added on as extra before the usual 7th-year manumission could take effect.

- ^ Berakot 47. Sadducees went as far as to hold slave owners responsible for any damage caused by their slaves; Yadayim 4:7. By contrast, pharisees acknowledged that slaves had independent thought – Yadayim 4:7

- ^ According to the traditional Jewish law, a slave is more like an indentured servant, who has rights and should be treated almost like a member of the owner's family. Maimonides wrote (Yad, Avadim 9:8) that, regardless whether a slave is Jewish or not, "The way of the pious and the wise is to be compassionate and to pursue justice, not to overburden or oppress a slave, and to provide them from every dish and every drink. The early sages would give their slaves from every dish on their table. They would feed their servants before sitting to their own meals ... Slaves may not be maltreated of offended — the law destined them for service, not for humiliation. Do not shout at them or be angry with them, but hear them out". In another context, Maimonides wrote that all the laws of slavery are "mercy, compassion and forbearance" – from Encyclopedia Judaica, 2007, vol. 18, p. 670

- ^ Freeman, Tzvi. "Torah, Slavery and the Jews". Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Abrahams, p. 100-101

- ^ Roth, p. 60

- ^ a b Hezser, pp. 3-5

- ^ Hezser, pp. 5-8

- ^ Hezser, p. 41

- ^ Hezser, p. 41-42

- ^ a b Abrahams, p. 99

- ^ Toch, Michael (2013). The Economic History of European Jews: Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill nV. pp. 178–190. ISBN 9789004235397. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Hastings, p. 619-620

- ^ Abrahams, p. 97, who cites Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh Deah, 267:14

- ^ Abraham, p. 97

- ^ Tacitus, Annals, 2:85

- ^ Suetonius, Tiberius, 36

- ^ Hezser, p. 43

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews

- ^ Abrahams, p. 96

- ^ Ransoming Captive Jews. An important commandment calls for the redemption of Jewish prisoners, but how far should this mitzvah be taken? Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine by Rabbi David Golinkin

- ^ Paul Johnson: A History of the Jews. 1987. p.240

- ^ "Suriname", The Historical Encyclopaedia of world slavery, Volume 1, by Junius, p. Rodriguez, p. 622

- ^ Reiss, p. 86

- ^ Schorsch, p. 60

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 622

- ^ Journal, Jewish (2013-12-26). "How culpable were Dutch Jews in the slave trade?". Jewish Journal. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Hebb, p. 153.

- ^ Hebb, p. 160

- ^ Hebb, p. 163, No 5

- ^ Drescher, p. 107: "A small fragment of the Jewish diaspora fled ... westward into the Americas, there becoming entwined with the African slave trade" ... they could only prosper by moving into high risk and new areas of economic development. In the expanding Western European economy after the Columbus voyages, this meant getting footholds within the new markets at the fringes of Europe, primarily in overseas enclaves. One of these new 'products' was human beings. It was here that Jews, or descendants of Jews, appeared on the rosters of Europe's slave trade."

- ^ a b c Austen, p. 134

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST (p 451): "Jewish mercantile influence in the politics of the Atlantic slave trade probably reached its peak in the opening years of the eighteenth century ... the political and the economic prospects of Dutch Sephardic [Jewish] capitalists rapidly faded, however, when the British emerged with the asiento [permission to sell slaves in Spanish possessions] at the Peace of Utrecht in 1713".

- ^ a b Drescher: JANCAST, p. 455: "only in the Americas — momentarily in Brazil, more durably in the Caribbean — can the role of Jewish traders be described as significant.", p. 455.

- ^ Herbert I. Bloom. "The Christian inhabitants [of Brazil] were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco and were among the leading slave-holders and slave traders in the colony", p. 133 of The Economic Activities of the Jews in Amsterdam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

- ^ Austen, p. 135: "Jews of Portuguese Brazilian origin did play a significant (but by no means dominant) role in the eighteenth-century slave trade of Rhode Island, but this sector accounted for only a very tiny portion of the total human exports from Africa."

- ^ "Slave trade [sic] was one of the most important Jewish activities here [in Surinam] as elsewhere in the colonies", p. 159, same book 2. The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Port Washington, New York/London: Kennikat Press, 1937), p. 159[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Roth, p. 292

- ^ Austen*, p. 135: "but the Dutch territories were small, and their importance shortlived."

- ^ a b c d Raphael, p. 14

- ^ Kritzler, p. 135: While the [Dutch West India] Company held a monopoly on the slave trade, and made a 240 percent profit per slave, Jewish merchants, as middlemen, also had a lucrative share, buying slaves at the Company auction and selling them to planters on an installment plan — no money down, three years to pay at an interest rate of 40-50 percent ... With their large profits — slaves were marked up by 300 percent ... — they built stately homes in Recife, and owned ten of the 166 sugar plantations, including "some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco". [Herbert Bloom quoted in the last sentence]

- ^ Wiznitzer, Arnold, Jews in Colonial Brazil, Columbia University Press, 1960, p. 70; quoted by Schorsch at p. 59: The West India Company, which monopolized imports of slaves from Africa, sold slaves at public auctions against cash payment. "It happened that cash was mostly in the hands of Jews. The buyers who appeared at the auctions were almost always Jews, and because of this lack of competitors they could buy slaves at low prices. On the other hand, there also was no competition in the selling of the slaves to the plantation owners and other buyers, and most of them purchased on credit payable at the next harvest in sugar. Profits up to 300 percent of the purchase value were often realized with high interest rates"

- ^ Schorsh, p. 60

- ^ Jonathan Schorsch. Jews and blacks in the early modern world, p. 61

- ^ Schorsch, p. 62: In Curaçao: "Jews also participated in the local and regional trading of slaves"

- ^ Drescher, JANCAST, p. 450

- ^ Cnaan, Liphshiz; Tzur, Iris (2013-12-26). "How culpable were Dutch Jews in the slave trade?". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Professor Jacob R. Marcus of Hebrew Union College in The Colonial American Jew (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970), Vol. 2, pp. 702-703

- ^ Bertram W. Korn, "Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865", in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, MA: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol. 3, p. 180 :

- ^ Historical Facts vs. Antisemitic Fictions: The Truth About Jews, Blacks, Slavery, Racism and Civil Rights (prepared under the auspices of the Simon Wiesenthal Center by Dr. Harold Brackman and Professor Mary R. Lefkowitz; 1993)

- ^ Drescher, EAJH. Vol 1 (p 415), Newport, RI: "Newport [Rhode Island] was the leading African slaving port during the eighteenth century and the only port in which Jewish merchants played a significant part. At the peak period of their participation in slaving expeditions (the generation before the Am. Revolution), Newport's Jewish merchants handled up to 10 percent of the Rhode Island slave trade. Incomplete records for other eighteenth-century ports in which Jews participated in the slave trade in any way show that for a few years they held at least partial shares in up to 8 percent of New York's small number of slaving voyages, usually from African to Caribbean ports.

- ^ Drescher, EAJ. Vol 1 (p 415): internal traffic within US (Korn 1973).

- ^ Susanna Ashton (September 12, 2014). "Slaves of Charleston". The Forward.

- ^ Ad from A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Together with corroborative statements verifying the truth of the work by Harriet Beecher Stowe, published by T. Bosworth, 1853

- ^ Information on Jacob Levin found at Jews and the American Slave Trade, by Saul S. Friedman, p. 157

- ^ Drescher, p. 109

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST, p. 447: "New Christian merchants managed to gain control of a sizeable, perhaps major, share of all segments of the Portuguese Atlantic slave trade during the Iberian-dominated phase of the Atlantic system. I have come across no description of the Portuguese slave trade that estimates the relative shares of the various participants in the slave trade by the racial-religious designation, but New Christian families certainly oversaw the movement of a vast number of slaves from Africa to Brazil during its first-century period [1600-1700]."

- ^ Austen, pp. 131-33

- ^ Foxman, Abraham. Jews and Money. pp. 130–35.

- ^ Austen, pp. 133-34

- ^ "Black Demagogues and Pseuo-Scholars", New York Times, July 20, 2002, p. A15.

- ^ Austen, pp. 131-35

- ^ Austen, p. 131:

John Hope Franklin and I ... were condoning a benign historical myth: that the shared liberal agenda of twentieth-century Blacks and Jews has a pedigree going back through the entire remembered past. ... Jewish students of Jewish history have known it was untrue and ... have produced a significant body of scholarship detailing the involvement of our ancestors in the Atlantic slave trade and Pan-American slavery. [The scholarship] had never been synthesized in a publication for non-scholarly audience. A book of this sort has now appeared, however, written not by Jews but by an anonymous group of African Americans associated with the Reverend Louis Farrakhan's Nation of Islam.

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST, p. 455: "only in the Americas — momentarily in Brazil, more durably in the Caribbean — can the role of Jewish traders be described as significant." .. but elsewhere involvemnent was modest or minimal, p. 455.

- ^ "Medieval Christians greatly exaggerated the supposed Jewish control over trade and finance and also became obsessed with alleged Jewish plots to enslave, convert, or sell non-Jews ... Most European Jews lived in poor communities on the margins of Christian society; they continued to suffer most of the legal disabilities associated with slavery. ... Whatever Jewish refugees from Brazil may have contributed to the northwestward expansion of sugar and slaves, it is clear that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery." – Professor David Brion Davis of Yale University in Slavery and Human Progress (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 89 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "The Jews of Newport seem not to have pursued the [slave trading] business consistently ... [When] we compare the number of vessels employed in the traffic by all merchants with the number sent to the African coast by Jewish traders ... we can see that the Jewish participation was minimal. It may be safely assumed that over a period of years American Jewish businessmen were accountable for considerably less than two percent of the slave imports into the West Indies" – Professor Jacob R. Marcus of Hebrew Union College in The Colonial American Jew (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970), Vol. 2, pp. 702-03 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "None of the major slavetraders was Jewish, nor did Jews constitute a large proportion in any particular community. ... probably all of the Jewish slavetraders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South." – Bertram W. Korn. Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789–1865, in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol 3, pp. 197-98 (cited in [1] Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine Shofar FTP Archive File at [2] [permanent dead link])

- ^ "Eli Faber takes a quantitative approach to Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade in Britain's Atlantic empire, starting with the arrival of Sephardic Jews in the London resettlement of the 1650s, calculating their participation in the trading companies of the late seventeenth century, and then using a solid range of standard quantitative sources (Naval Office shipping lists, censuses, tax records, and so on) to assess the prominence in slaving and slave owning of merchants and planters identifiable as Jewish in Barbados, Jamaica, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston, and all other smaller English colonial ports. He follows this strategy in the Caribbean through the 1820s; his North American coverage effectively terminates in 1775. Faber acknowledges the few merchants of Jewish background locally prominent in slaving during the second half of the eighteenth century but otherwise confirms the small-to-minuscule size of colonial Jewish communities of any sort and shows them engaged in slaving and slave holding only to degrees indistinguishable from those of their English competitors" Book Review Archived 2008-10-11 at the Wayback Machine of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight, and Jews and the American Slave Trade by Saul S. Friedman. The Journal of American History Vol 86. No 3, December 1999

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST, p. 455:

- ^ Drescher, EAJH — Vol 1. "The available evidence indicates that the Jewish network probably counted for little in Atlantic slaving. The few cases of long-term Jewish participation in the eighteenth-century slave trades offer evidence of cross-religious networks as keys to their success. In case after case, Jews who participated in multiple slaving voyages ... linked themselves to Christian agents or partners. It was not as Jews, but as merchants, that traders ventured into one of the great enterprises of the early modern world." Drescher, in Ency Am. J. Hist., p. 416.

- ^ Drescher, pp. 107-108

- ^ Encyclopedia of American Jewish history, Volume 1, p. 199

- ^ Book Review Archived 2008-10-11 at the Wayback Machine of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight (by Faber), and Jews and the American Slave Trade (by Friedman), at The Journal of American History, Vol 86, No 3 (December 1999)

- ^ Ralph A. Austen, "The Uncomfortable Relationship: African Enslavement in the Common History of Blacks and Jews," Maurianne Adams and John H. Bracey, ed., Strangers and Neighbors: Relations Blacks and Jews in the United States (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 131.

- ^ a b Greenberg, p. 110

- ^ a b c Reiss, p. 88

- ^ Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade, pp. xiii, 123-27.

- ^ Maxwell Whiteman, "Jews in the Antislavery Movement", Introduction to The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: The Narrative of Peter and Vina Still (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1970), pp. 28, 42

- ^ Duhaut, Noëmie (2021). ""A French Jew Emancipated the Blacks": Discursive Strategies of French Jews in the Age of Transnational Emancipations". French Historical Studies. 44 (4): 645–674. doi:10.1215/00161071-9248713. S2CID 240903964.