Lloyd Aspinwall

Lloyd Aspinwall | |

|---|---|

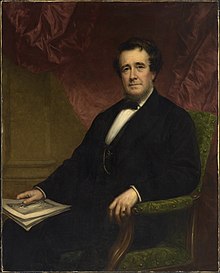

Aspinwall during the Civil War, c. 1862 | |

| Born | John Lloyd Aspinwall December 12, 1834 |

| Died | September 4, 1886 (aged 51) Bristol, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Resting place | Green-Wood Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Harriette Prescott D'Wolf

(m. 1856) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | William Henry Aspinwall Anna Lloyd Breck |

| Relatives | James Renwick Jr. (brother-in-law) James Roosevelt I (cousin) |

John Lloyd Aspinwall (December 12, 1834 – September 4, 1886) was an American lawyer and soldier who served in the U.S. Civil War, achieving the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. National Guard.[1]

Early life

Lloyd, as he was commonly known, was born on December 12, 1834, in Manhattan. He was the second child and oldest son of five children born to William Henry Aspinwall (1807–1875)[2][3] and Anna Lloyd (née Breck) Aspinwall (1812–1885). His siblings included Anna Lloyd Aspinwall (1831–1880), who married architect James Renwick Jr. (1818–1895),[4] Rev. John Abel Aspinwall (1840–1913), who married Julia Titus and Bessie Mary Reed, Louisa Aspinwall (1843–1913), who married John Wendell Minturn, son of merchant Robert Bowne Minturn, and Katharine Aspinwall (1847–1924), who married Ambrose Cornelius Kingsland, the son of New York Mayor Ambrose Kingsland. His father was a prominent merchant with the Howland & Aspinwall and was also a co-founder of both the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and Panama Canal Railway, companies which revolutionized the migration of goods and people to the Western Coast of the United States.[5]

His maternal grandparents were Catherine Douce (née Israel) Breck (1789–1864)[6] and George Breck (1784–1869), the brother of U.S. Representatives Samuel Breck and Daniel Breck.[7] His uncle was Rev. James Lloyd Breck, an Episcopal missionary,[8] and his aunt was Jane Breck, who married paternal uncle John Lloyd Aspinwall.[8]

His paternal grandparents were John Aspinwall (1774–1847), a dry goods merchant firm of Gilbert & Aspinwall,[9] and Susan Howland (1779–1852).[10] The Howland family was descended from John Howland, a signor of the Mayflower Compact[11] and the Aspinwall family was descended from William Aspinwall, who was among the first settlers of New England.[2][12] His aunt, Mary Rebecca Aspinwall (1809–1886) was married to Isaac Roosevelt, the grandfather of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[13] His great-aunt, Harriet Howland, was the third wife of Isaac's father, New York State Assemblyman James Roosevelt.[14] His paternal great-grandfather, Captain John Aspinwall, was one of the most prominent shipmasters of the New York merchant marine before the American Revolutionary War.[15]

Career

Aspinwall, a New York attorney,[16] succeeded his father in the firm of Howland & Aspinwall,[9] and was said to have "entered into the business full of enthusiasm and business energy. He had only fairly started upon a business career when the war began."[1]

He also served as a trustee of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge, which built the Brooklyn Bridge from 1869 to 1883.[17]

He was a staunch Republican, although he never held elected office. He was encouraged to seek the Mayorship of New York in 1880, considered it, but declined to seek the nomination and William Russell Grace, an anti-Tammany Democrat won election following the term of Edward Cooper.[1]

U.S. Civil War

During the U.S. Civil War, he served as a Union Army officer in the 22nd New York State Militia, which he helped organize as the "Minor Grays"[18] and included John E. Parsons, George deForest Lord and Benjamin F. Butler.[19] Beginning in 1854, Aspinwall had trained for eight years with the New York state troops, rising from the ranks to the staff of the Fourth Artillery.[18] On May 28, 1862, he enlisted in New York City as a lieutenant colonel and was commissioned into Field & Staff New York 22nd Infantry. After mustering out on September 5, 1862, he was again commissioned, on June 18, 1863, into the Field & Staff New York 22nd Infantry, only to muster out on July 24, 1863. He also served as an aide to General Ambrose Burnside before the Battle of Fredericksburg,[20] and was sent to give President Abraham Lincoln the first report of the battle.[1]

After the war ended in 1865, Aspinwall returned to business, but stayed close to the military. He served in, and was later promoted to brigadier general of the 4th Brigade,[21] in the U.S. National Guard. At the same time, he was president of the State Military Association and was active in establishing the rifle range which was then incorporated into the military system. He was also a founder of the Army and Navy Club and became its president in 1877. In 1880, New York Governor Alonzo B. Cornell appointed him Engineer-in-Chief on his military staff, which he held until Cornell's term as governor ended on December 31, 1882.[1]

Society life

He was a founding member of the Jekyll Island Club in Jekyll Island, Georgia.[22] He was supposed to serve as the club's first president, however, he died unexpectedly on September 4, 1886, more than a year before the club would officially open.[1]

He was a member of the Union Club of New York.[18] His father, who was a co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[23] owned works by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Antonio da Correggio, Diego Velázquez, Bartholomeus van der Helst, Teniers, Peter Paul Rubens, Philips Wouwerman, Cuyp, Ary Scheffer, Gerard, Dow, Nicolaes Pieterszoon Berchem, Titian, Adriaen Brouwer, Gerard ter Borch, Paul Veronese, Mieris, and Leonardo da Vinci, Romney, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Jean-Baptiste Madou. He inherited several of the paintings.[24]

Personal life

On April 16, 1856,[25] Aspinwall was married to Harriette Prescott D'Wolf (1835–1888) in Bristol, Rhode Island.[26] She was the daughter of William Bradford D'Wolf (1810–1852) and Mary (née Russell) D'Wolf (1805–1881),[18] and a granddaughter of U.S. Senator and Representative from Rhode Island James DeWolf.[22] Together, Lloyd and Harriette were the parents of:[27]

- William H. Aspinwall (1857–1910), married to Anna Lloyd Breck.[28]

- Lloyd Aspinwall, Jr. (1862–1899),[29] who married Cornelia Georgiana Sutton (1862–1897),[30] daughter of merchant Cornelius Kingsland Sutton.[31]

- Russell D'Wolf Aspinwall (1871–1874), who died young.[27]

Aspinwall died unexpectedly of apoplexy on September 4, 1886, in Bristol, Rhode Island.[1] He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Descendants

Through his son Lloyd, who died of Bright's disease at the age of 37, he was the grandfather of Lloyd Aspinwall (1883–1952), a member of the Amateur Comedy Club in Santa Barbara, California,[32] and Beatrice Aspinwall (1889–1897), who died a few days after her mother's death in 1897.[29]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Obituary.; Lloyd Aspinwall". The New York Times. 5 September 1886. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Obituary: William H. Aspinwall" (PDF). New York Times. January 19, 1875. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ "THE FUNERAL OF WILLIAM H. ASPINWALL; THE CHURCH OF THE ASCENSION CROWDED A HANDSOME TRIBUTE TO A NOBLE LIFE". The New York Times. January 22, 1875. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Rossiter; Brown, John Howard (1904). The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans ... Biographical Society. p. 78. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Levy, D.A. (February 14, 2004). "William Henry Aspinwall". The Maritime Heritage Project. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ Garraty, John Arthur; Carnes, Mark Christopher; Societies, American Council of Learned (1999). American National Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 691. ISBN 9780195127805. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Fuller, Margaret (2001). My Heart is a Large Kingdom: Selected Letters of Margaret Fuller. Cornell University Press. p. 317. ISBN 0801437474. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ a b Prichard, Robert W. (2014). A History of the Episcopal Church (Third Revised ed.). Church Publishing, Inc. p. 216. ISBN 9780819228772. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ a b Barrett, Walter (1864). The Old Merchants of New York City, Second Series. New York: Carleton, Publisher. p. 337. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Aspinwall, John; Collins, Aileen Sutherland (1994). Travels in Britain, 1794-1795: the diary of John Aspinwall, great-grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, with a brief history of his Aspinwall forebears. Parsons Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780963848765. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Roosevelt Genealogy". fdrlibrary.marist.edu. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Aspinwall, Algernon Aikin (1901). The Aspinwall Genealogy. Rutland, VT: The Tuttle Co., Printers. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Whittelsey, Charles Barney (1902). The Roosevelt Genealogy, 1649-1902. Hartford, Connecticut: Press of J.B. Burr & Company. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Kienholz, M. (2008). Opium Traders and Their Worlds-Volume One: A Revisionist Exposé of the World's Greatest Opium Traders. iUniverse. p. 403. ISBN 9780595910786. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ American Society of Civil Engineers (1897). Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. American Society of Civil Engineers. p. 598. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ District of Columbia Court of Appeals; Circuit), United States Court of Appeals (District of Columbia (1895). Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia. Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company. pp. 465–6. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ McCullough, David (2011). David McCullough Library E-book Box Set: 1776, Brave Companions, The Great Bridge, John Adams, The Johnstown Flood, Mornings on Horseback, Path Between the Seas, Truman, The Course of Human Events. Simon and Schuster. pp. 610–1. ISBN 9781451658255. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d Hall, Henry (1895). America's Successful Men of Affairs: The city of New York. New York Tribune. pp. 31–2. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Hicks, Paul DeForest (2016). John E. Parsons: An Eminent New Yorker in The Gilded Age. Easton Studio Press, LLC. pp. 57–8. ISBN 9781632260741. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Richman, Jeff (June 15, 2015). "Servant and Civil War Officer". www.green-wood.com. Green-Wood Cemetery. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Eicher, John; Eicher, David (2002). Civil War High Commands. Stanford University Press. p. 588. ISBN 9780804780353. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ a b Hutto, Richard Jay (2005). The Jekyll Island Club Members. Indigo Custom Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9780977091225. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "William Henry Aspinwall (1807-1875)". Trainweb. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ "Archives Directory for the History of Collecting". research.frick.org. Frick Art & Historical Center. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "NYC Marriage & Death Notices 1843-1856". www.nysoclib.org. New York Society Library. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

MARRIED 1856: At Bristol, N.J., on Wednesday, April 16, by Right Rev. Bishop Clark, Lloyd Aspinwall, Esq., of this City, to Harriette, daughter of Wm. Bradford D'Wolf, Esq., of the former place.

- ^ Perry, Calbraith Bourn (1913). The Perrys of Rhode Island, and Tales of Silver Creek: The Bosworth-Bourn-Perry Homestead, Rev. and Enl. from a Lecture...at the Public Library, Cambridge, N.Y., April 13, 1909. T. A. Wright. p. 25. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ a b Perry, Calbraith Bourn (1902). Charles D'Wolf of Guadaloupe, his ancestors and descendants: being a complete genealogy of the "Rhode Island D'Wolfs," the descendants of Simon De Wolf, with their common descent from Balthasar De Wolf of Lyme, Conn. (1668) : with a biographical introduction and appendices of the Nova Scotian de Wolfs and other allied families. Higginson Books Co. p. 162. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "William H. Aspinwall". The New York Times. 16 November 1910. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ a b "DEATH OF LLOYD ASPINWALL.; One-Time Well-Known and Wealthy Clubman Dies in Comparative Poverty". The New York Times. 11 July 1899. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Nina G. Aspinwall". The New York Times. January 8, 1897. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Quiz: A Weekly Journal for the Family. 1881. p. 66. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "DEATHS. ASPINWALL--Lloyd". The New York Times. 8 April 1952. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

External links

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !