New York Port of Embarkation

The New York Port of Embarkation (NYPOE) was a United States Army command responsible for the movement of troops and supplies from the United States to overseas commands. The command had facilities in New York and New Jersey, roughly covering the extent of today's Port of New York and New Jersey, as well as ports in other cities as sub-ports under its direct command. During World War I, when it was originally known as the Hoboken Port of Embarkation with headquarters in seized Hamburg America Line facilities in Hoboken, New Jersey, the Quartermaster Corps had responsibility. The sub-ports were at Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia and the Canadian ports of Halifax, Montreal and St. Johns. The World War I port of embarkation was disestablished, seized and requisitioned facilities returned or sold and operations consolidated at the new army terminal in Brooklyn. Between the wars reduced operations continued the core concepts of a port of embarkation and as the home port of Atlantic army ships. With war in Europe the army revived the formal New York Port of Embarkation command with the New York port, the only Atlantic port of embarkation, taking a lead in developing concepts for operations.

In World War II the NYPOE, now under the new Transportation Corps, was the largest of eight Port of Embarkation commands, the second largest being the San Francisco Port of Embarkation and the second largest on the East Coast being Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation. Originally it had the army facilities in Charleston, South Carolina as a sub-port until it was elevated to the Charleston Port of Embarkation as a separate command. The cargo sub-port at Philadelphia remained under the command of NYPOE throughout the war. By the end of the war 3,172,778 passengers, counting 475 embarked at the Philadelphia cargo port, and 37,799,955 measurement tons of cargo had passed through the New York port itself with 5,893,199 tons of cargo having passed through its cargo sub-port at Philadelphia—about 44% of all troops and 34% of all cargo passing through army ports of embarkation.

New York POE in concept development

The formation and development of the then Hoboken Port of Embarkation early in World War I was the basis for a massive and complex Army command by the time the concept reached its full development in World War II. As the first and by far the largest POE in World War I NYPOE served as the model for general POE concepts and continued its role as the largest of the ports throughout World War II. Even though the First World War POE command was disbanded the interwar years saw some of the same concept and core functions operating at the two major Army ports at Brooklyn Army Base and Fort Mason in San Francisco.[1]

When war broke out in Europe in 1939 only New York was operating as a port of embarkation on the Atlantic seaboard.[2] As the nation prepared for conflict a supply center in New Orleans was elevated to a POE with another facility at Charleston becoming a sub-port of New York POE with the War Department developing the concept for the fully developed Port of Embarkation concept operating after entry into the war.[2]

An Army "Port of Embarkation" (POE) is not simply some Army shipping terminal.[3] An Army POE was a command structure and interconnected land transportation, supply and troop housing complex devoted to efficiently loading overseas transports.[4] The scope of the World War II POE is summarized in Army Regulations: AR 55-75, par. 2B, 1 June 1944:

The commanding officer of a port of embarkation will be responsible for and will have authority over all activities at the port, the reception, supply, transportation, embarkation, and debarkation of troops, and the receipt, storage, and transportation of supplies. He will see that the ships furnished him are properly fitted out for the purpose for which they are intended; he will supervise the operation and maintenance of military traffic between his port and the oversea base or bases; he will command all troops assigned to the port and its component parts, including troops being staged, and will be responsible for the efficient and economical direction of their operations. He will be responsible for the furnishing of necessary instructions to individuals and organizations embarked or debarked at the port ... He will be responsible for taking the necessary measures to insure the smooth and orderly flow of troops and supplies through the port. (AR 55-75, par. 2B, 1 Jun 44. Quoted Chester Wardlow : pages 95–96, The Transportation Corps: Responsibilities, Organization, and Operations)[note 1]

Any primary POE could have sub-ports and cargo ports even in other cities or temporarily assigned for movements between the United States to one of the overseas commands it normally served. In World War I port facilities in Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia and even in Canada served as sub-ports to the NYPOE.[5][6] An important special cargo function involved mail in which the POE was required to ensure all mail sacks were properly labeled, met the earliest sailing date and were distributed in such a way that loss of one ship would not destroy all mail destined for a unit.[7]

For troop movements the most critical timing factor was availability of the transports and sailing dates so that the most effective means of minimizing delays at the port was for the POE to control the movement of troops from their home stations to the port as well as having responsibility for ensuring troops were properly equipped and prepared for overseas deployment.[8][9] Most troops were embarked destined for arrival at rear area assembly points, but when destined for landing against hostile forces the ports "combat loaded" troops under different procedures made in consultation with the force commander that included billeting combat teams together at the port and loading team equipment and supplies aboard the assault vessels for efficient unloading.[10]

In one respect the POE Command extended even to the troops and cargo embarked on ships until they were disembarked overseas through "transport commanders" and "cargo security officers" aboard all troop and cargo ships under Army control, either owned, bareboat chartered and operated or charter with operation by War Shipping Administration (WSA) agents that were appointed and under the command of the POE.[11] Troops embarked aboard all vessels except U.S. Naval transports remained under overall command of the port commander until disembarked overseas.[12] That command was exercised by the Transport Commander whose responsibilities extended to all passengers and cargo but did not extend to operation of the ship which remained with the ship's master.[13] On large troop ships the transport command included a permanent staff of administration, commissary, medical and chaplain personnel.[14] The cargo security officers were representatives of the port commander aboard ships only transporting Army cargo.[15]

World War I operations

The Hoboken Port of Embarkation, with New York Port of Embarkation also in use by the close of the war, was formally established on 27 July 1917 with a port commander having been assigned on 7 July.[16][17] The Army quickly recognized demands of World War I shipping overseas required unified command of operations of the Water Transportation Branch, Quartermaster Corps and the Army camps and depots through which troops and supplies passed.[16] In early June Major General J. Franklin Bell, commanding the Army's Department of the East on Governors Island was instructed to assume the functions of the commander of such a Port of Embarkation as the port organized.[16] It quickly became clear the United States involvement in the war overseas required a central, separate, more flexible and responsive organization with direct oversight from the War Department in Washington, D.C. Previous War Department planning had envisaged ports of embarkation under single commanders.[16]

The first headquarters was established at Hoboken, New Jersey using facilities and piers seized from the German owned North German Lloyd and Hamburg-American steamship lines on the Hudson River.[16] The first commander was Brigadier General William M. Wright serving from 1 July to 1 August 1917.[5] On 1 August 1917 Major General David C. Shanks assumed command as the ports of embarkation came under the Embarkation Service until 27 September 1918 when ports were made coordinate agencies directly under the General Staff.[16][5] The port was briefly under command of two Brigadier Generals, William V. Judson and George H. McManus from 9 September 1918 until General Shanks resumed command on 5 December 1918.[5]

In the early stages of the port's operation during World War I the cargo functions were located in Brooklyn and New Jersey with troop movements largely out of Hoboken, where the command was located, and nearby Manhattan piers seized from German lines with passenger facilities.[16]

By war's end the NYPOE, again under Major General David C. Shanks, had expanded to a staff of 2,500 officers, embarkation camps, hospitals, twelve piers and seven warehouses in Hoboken, in Brooklyn eight piers and 120 warehouses of which six piers were also Bush Terminal Company assets, and two Army Supply Base warehouses and, in the North River, Manhattan three piers covering a total of fifty-seven acres.[18]

Three embarkation camps, Camp Merritt having a 38,000 transient troop capacity, Camp Mills with 40,000 capacity and Camp Upton with 18,000 capacity came under the direct command of the Port of Embarkation while Camp Dix remained under War Department control but served as an embarkation camp for the port.[18] The command included four embarkation hospitals and five debarkation hospitals, one general hospital and one auxiliary hospital along with two base hospitals.[6]

The ports of Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia served as sub-ports and the Canadian ports of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Montreal and St. John's, Newfoundland as subsidiary ports under the NYPOE.[5][6]

The need for more permanent dockside Army passenger, warehousing and shipping facility was recognized and the Brooklyn Army Base, redesignated the Brooklyn Army Terminal (BAT) 1 October 1955,[19] was constructed from existing terminal and docking facilities in Owls Head, Brooklyn, not far from Fort Hamilton, beginning in 1918.

The port managed the return of the from France during 1919 and of the American Forces in Germany, 1919–1923 as well as postwar transport related to support of forces in Puerto Rico and the Panama Canal Zone.[18] In December 1919 USAT Buford, home ported at the port, transported Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman along with 240 people considered Communists and radicals from the NYPOE to Hango, Finland.[20]

General Shanks' command and the NYPOE were discontinued 24 April 1920 with functions turned over to the General Superintendent, Army Transport Service, Army Base Brooklyn.[5] Though the command had changed and the port itself reduced in size from the wartime years to the new Army terminal continued to be referred to as the New York Port of Embarkation with ships home ported at "New York POE, Army Supply Base, Brooklyn, NY," as were the transports USAT America, USAT American Legion, USAT Chateau Thierry, USAT Great Northern, USAT Hunter Liggett and others.[21]

In later stages and postwar years, with the permanent Brooklyn facilities becoming the center of operations, New York Port of Embarkation (NYPOE) replaced the former term and was the official term during World War II.[16][5]

Between the wars

With official discontinuation of the command structure at the end of World War I the port, along with the ports at San Francisco and New Orleans also being used by the Army, became a depot for personnel and supplies for the overseas facilities it served without coordinating functions.[22] The command was under a Superintendent, Quartermaster Corps, Army Transport Service reporting to the Quartermaster General.[22] On 6 May 1932 the New York Port of Embarkation was reactivated with command at Army Base Brooklyn consolidating command of the Atlantic branch of the Army Transport Service, the New York General Quartermaster Depot at the Army base and the Overseas Replacement and Discharge Service at Fort Slocum.[5]

World War II

Major General Homer M. Groninger assumed command from a series of short term commanders on 7 November 1940 and remained in command throughout the war in Europe during which he advanced the port's role in primary supply responsibility for the overseas theater commands.[5][23] NYPOE became a prototype for the expansion and activation of the other Army Ports of Embarkation with most of the basic system for handling requisitions from overseas commands, planning shipments and cargo loading developed there.[24][25] In 1939 when war was declared in Europe NYPOE was the only formally operating port of embarkation on the Atlantic.[2] During the period between that event and entry of the United States into the war two sub-ports were established under NYPOE:

- Charleston established to relieve pressure on NYPOE with initial responsibility largely centered on the West Indies and Caribbean. After the United States entered the war Charleston became a POE in its own right.[2]

- New Orleans established as a sub-port to support the Panama Canal Department but later became involved in support of Caribbean, South Atlantic, and Pacific commands as the New Orleans Port of Embarkation.[26]

On 17 December 1941 all depots and ports of embarkation came under the Chief of the Transportation Branch, G-4, with the Chief of Transportation, Services of Supply, gaining command oversight in March when that position was established.[22] Central control tightened and was coordinated under a Transportation Control Committee that extended to all the military services, the War Shipping Administration (WSA), Office of Defense Transportation and allied British Ministry of War Transport that controlled all movements of troops and freight including Lend Lease moving through the ports.[22]

Later in the war, with full ports of embarkation established in Boston and Hampton Roads, a cargo sub-port under NYPOE was established at Philadelphia.[26] At the end of the war, despite the accomplishments of the other ports and sub-ports, the NYPOE remained the single port with the largest passenger and cargo numbers and only the San Francisco Port of Embarkation rivaling its role in the supported theater of war.[27]

The single issue driving nearly all the command's functions was availability and movement of shipping that was coordinated with the port but not under the sole control of the port.[8][9] Troops and supplies had to be available to meet ship availability, the convoy cycle and sailing dates and adjustments made for events concerning ships from mechanical to weather and other demands.[28] Convoy schedules were Navy controlled and all ship sailings required Navy clearance.[29] Convoy schedules were determined in Washington by Navy and War Departments with a pre-sailing convoy conference held by the Office of the Port Director with local Navy, commanders of the escort vessels and masters of the convoy vessels attending to ensure final details of convoy assembly, operation and emergency actions were determined and understood.[30]

Major facilities

Embarkation camps

Embarkation camps were staging areas established to house and prepare troops for a period of usually a week, but sometimes up to two weeks, before embarkation overseas.[31] At NYPOE the period in 1944 average time in camp ranged from 7.1 to 11.7 days.[32] The camps were under the direct command of the Port Commander with responsibility to complete final training, equipping and other preparation of troops in coordination with troopship and convoy schedules.[33]

- Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, with troop capacity of over 37,500.[34] Troops were usually moved by rail to Jersey City, New Jersey to board ferry boats for the embarkation piers and transfer to the troop transports.[35]

- Camp Shanks in Orangeburg, New York, dubbed "Last Stop USA", with troop capacity of over 34,600.[34] About 1,300,000 troops passed through this camp.[36] Troops were moved by rail to Jersey City or marched to Piermont, New York to board a ferry for the embarkation piers to transfer to the troop transports.[35][36]

- Fort Hamilton with a troop capacity of 5,700 was used as needed.[34]

- Fort Slocum served as a Transportation Corps officer training center and as a staging area for NYPOE as needed.[37][36]

Subports

Boston was a sub-port under the New York Port of Embarkation command until July 1942 when it became a port in its own right.[38] Philadelphia was established and remained as a cargo port under the command of the New York Port of Embarkation.[2] Some 475 passengers embarked at Philadelphia in 1943 and 1944 with their numbers included in the NYPOE total.[38] Philadelphia was an important supplement to NYPOE in explosives shipment with its original two ammunition and explosives berths expanded to six, matching the capacity at New York's Caven Point terminal.[39]

Terminals

The port facilities included ten terminals:

- Brooklyn Army Base, 58th Street, Brooklyn, with headquarters, piers, 3,800,000 square feet of storage space and sidings for 450 rail cars.[40]

- Bush Terminal, near Brooklyn Army Base, at 46th Street, Brooklyn, with eight piers, 1,500,000 square feet of storage and sidings for 150 rail cars.[40]

- Staten Island Terminal, Stapleton, with ten piers, 4,500,000 square feet of storage, sidings for 235 rail cars and large open storage facilities.[40]

- Howland Hook Terminal, Staten Island, for petroleum products refined at Bayonne and Elizabeth, New Jersey.[40]

- Fox Hills, Staten Island, training area for Army Port Battalions with housing for port personnel.[40]

- Port Johnson, Bayonne, New Jersey with open storage facilities and focal point for preparing and processing combat vehicles for shipment.[40]

- North River, Manhattan, the principal troop embarkation with seven piers to which troops were brought by ferry connecting rail terminals serving embarkation camps.[40]

- Army Postal Terminal with Army Post Office at 464 Lexington Avenue, Manhattan and a Postal Concentration Center between 43rd and 46th Streets at Northern Boulevard in Long Island City.[40] The bulk of mail destined for the European Theater passed through NYPOE with the port responsible for ensuring mail sacks were properly addressed and loaded for earliest delivery without undue risk to an overseas command's entire mail delivery through loading on a single ship that might be lost.[7] During the Christmas rush of 1944 NYPOE handled about 2,600,000 mail bags.[7]

- Special Services Supply Terminal with facilities in Brooklyn and Manhattan that among other items shipped 4,000,000 magazines and 5,000,000 booklets to overseas troops.[40]

- Caven Point, Jersey City, New Jersey, an ammunition and explosives loading facility with a pier for direct loading of ships from rail cars.[40][41] The facility, with misgivings due to its proximity to inhabited areas, was built as an expansion of the Lehigh Valley Railroad Claremont terminal with six finger piers after the Navy's acquisition of the Bayonne Terminal made it unavailable for Army use.[41]

Associated facilities

- Camp Mitchel at Mineola[citation needed]

- Camp Upton at Yaphank on Long Island[citation needed]

- Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania was originally a Transportation Corps facility, associated with the port though not under the command of the NYPOE, where port troops were trained.[42]

General organization

While the precise organization of each of the ports was left largely to the commanders by the close of the war a general arrangement had become uniform in overall structure:[43]

- Overseas Supply Division: Handled supply requisitions from overseas commands served by the port, requisitioned supplies from sources and scheduled movement of supplies from points of origin to transports in accordance with sailings.[43]

- Port Transportation Division: Responsibility for both passenger and cargo movements to the port, between port facilities and coordinating with other divisions on loading and unloading transports.[43]

- Troop Movement Division: Controlled movement of troops through the port with responsibility for troop processing, billeting planning and coordinating troop movements with other divisions.[43]

- Initial Troop Equipment Division: Controlled movement of equipment, both accompanying and shipped separately but assigned to units moving through the port. Supervised port functions of ensuring final outfitting of troops before embarkation.

- Water Division: Responsible for vessel loading/discharge, operation, maintenance, repair, and conversion. Employed vessel crew and port stevedores. Responsible for pier, dock, wet storage basins and marine repair shops.[43]

Supply

That supply function created differences between the Army's supply and transportation organizations that were not resolved until early 1943 in a cooperative scheme.[44] In particular the shortage of shipping had complicated all matters of supply with the ports making every attempt to use available space so that separate supply and transportation requirements were driving inefficiencies.[45] WSA mandates to use available shipping space had driven the ports to fill every available space so that some material not actually required by the overseas command was loaded with the result that NYPOE had failed to heed supply instructions to cease automatic ammunition shipping to North Africa and "Ammunition and ration stocks in North Africa early in 1943 rose to embarrassingly high levels" due to consideration of those shipping requirements over supply requirements.[45]

The resolution was that neither supply nor transportation would take control but would work closely together under the Commanding General, Army Service Forces.[46] Theater commands placed supply orders through the ports of embarkation in a system largely developed at NYPOE as a result of experience gained in supplying forces in North Africa.[25] The supply cycle was geared to convoy sailings which were under Navy control with the NYPOE coordinating with Navy and controlling supply movement from depots to the piers and ships and even coordinating with production schedules to efficiently meet the transportation requirements.[47]

For the mobilization of material, 60 temporary warehouses with over 3 million square feet of space were constructed at Fort Jay on the south half of Governors Island.[citation needed]

The Army was responsible for the majority of explosives shipping with its own requirements, including the new requirement for large bombs for its air forces and lend-lease shipments to both Britain and the Soviet Union.[48] Early in the war New York had been a focal point and in light of previous disasters, including the Black Tom disaster in Jersey City during the previous war there was considerable concern to minimize multiple steps in handling such cargo.[48] When the Navy acquired the terminal at Bayonne the Army was forced to develop an explosives terminal closer to Manhattan than it desired at Caven Point with work on a six pier facility begun August 1941 and completion in June 1942.[41] Despite intense safety efforts and concerns there was an incident at Caven Point in which the ship El Estero caught fire and had to be scuttled in the harbor.[49][50] To lessen munitions concentration in NYPOE expansion of the Philadelphia munitions capability and dispersal of such facilities for all ports was sought.[51]

Troop movements

As with supply, the most critical timing factor in troop movements was availability of the transports and sailing dates.[8][9] To minimize delays and time in embarkation camps at the port the NYPOE controlled troop movements from their home stations or bases to the port where NYPOE had final responsibility for ensuring troops were properly equipped and prepared for overseas deployment.[8][52] Large movement of troops toward ports were conducted in secrecy to prevent sabotage en route and in particular to avoid alerting agents of possible large troop sailings.[53] After initial problems, including good will efforts of civic organizations to support troops and even police radio traffic, troop movements came under increasing secrecy with restrictions imposed on railroads and even the Red Cross.[54] Not all communications could be secured but details were conveyed in secure communications between Army's Traffic Control Division, the port and the Army railroad regulating stations.[53]

A particularly complicated part of troop's final processing was the port's responsibility of matching troops and schedules with equipment not issued at the home base, but arriving at the port from specialized depots and even manufacturers.[55] The process was covered in directives and the NYPOE produced a film detailing the important procedures prescribed by the Preparation for Overseas Movement directives.[56] The theater destination of troops was advised in general terms about one week before departure through a "loading cable" identifying the troops expected to be embarked by ship and expected sailing date so that the theater could prepare for the ship's and troop's arrival.[57] The theater was notified by "sailing cable" of the actual sailing date and by an airmailed manifest of the final loading of troops and cargo dispatched.[57]

Other services and civilians transported aboard Army controlled ship were handled by the port, though not necessarily passing through the port's embarkation camps. The Special Navy Advance Group 56 (SNAG 56) that established Navy Base Hospital Number 12 at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, England, was sent by train from a Naval Training Center at Lido Beach on Long Island, using "devious routes," to Jersey City where the unit boarded a ferry taking them to pier 86 in Manhattn.[58] There, while a band played and the Red Cross served their last coffee and doughnuts, they boarded "N.Y. 40", the NYPOE code designation for Aquitania, which got underway the morning of 29 January 1944 with some 1,000 Navy and 7,000 Army personnel for arrival at Greenock, Scotland 5 February.[58]

Other functions

Staging areas

The embarkation camps, or staging areas, were an integral part of the port and gained importance after an initial idea of transporting troops directly from home stations to ship-side were rejected.[59] The most important factor was to prevent the delay or sailing not fully loaded of vessels that were in critically short supply by having troops at the port before anticipated departure.[59] Secondly, the port was responsible for ensuring units were at full strength, fit and fully equipped before boarding transports and maintained replacement pools to replace either missing or unfit troops.[60] Command of the troops on arrival at the staging area passed to the port commander for the duration of their stay and to the port's transport commander until disembarked.[11][61] The camps were also to be used in a reverse process for returning troops and prisoners of war, though the latter were generally processed through the ports quickly to camps in the interior.[62]

Medical

The port, through the processing in the staging areas, was responsible for final medical processing that included a physical with particular attention to detecting infectious or contagious diseases that could cause epidemic aboard crowded troop ships or other conditions rendering a person unfit for overseas duty.[63] The ports, in conjunction with the Medical branch, attempted to render troops unfit for minor reasons fit for departure with their units with medical, dental and even provision of proper eyeglasses.[63]

During spring 1943 NYPOE issued instructions for transport surgeons, a Medical Corps officer on the transport commander's staff and thus within the NYPOE command, detailing care of both out and in bound troops and their responsibilities in the process of transferring patients from the ships to the port.[64] By the end of 1943 those instructions were adopted by all the ports and the basis for a general instruction covering Army hospital ships for the European and Mediterranean theaters that were all assigned to the Charleston Port of Embarkation.[65]

Early in the war the primary evacuation of wounded from Atlantic war zones to the United States was by return voyages of troop ships during which transport surgeons sent patient lists that contained debarkation information including whether by litter or walking, baggage and valuables, diagnosis, needed treatment to the port commander and, before arrival, a debarkation tag for each patient.[66][67] On the transport's arrival the NYPOE was responsible for unloading patients and ordering them sent to Tilton General Hospital at Fort Dix or Lovell General Hospital at Fort Devens or, if necessary, kept in the port's own hospital facilities during waiting periods.[68] The port continued to handle patients returning by ordinary transport even after specialized hospital ships began operation.

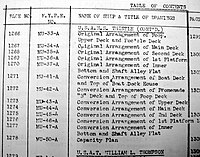

Ship maintenance and conversion

Among the functions of the port was maintenance and planning modifications to Army transports including conversions to hospital ships.[69] Plans for six Liberty ship conversions were made by naval architects Cox and Stevens with the remainder of the ship plans being done by the Maintenance and Repair Branch of the Water Division in coordination with the Surgeon General's Office.[70]

Debarkation, redeployment and repatriation

In a reverse process, relatively small before VE Day, the port was a port of disembarkation for mixed groups composed mostly of members of other services, Allied forces, civilians and prisoners of war.[71] Throughout the war patients had been returned home by a mix of troop ships and later hospital ships with the port responsible for debarking the patients for transfer to hospitals.

After the war in Europe ended with the port shifting from sending troops overseas to receiving troops arriving home General Groninger was transferred to command the San Francisco Port of Embarkation.[72] The priority was direct transfer of troops from Europe to the Pacific, but a significant portion were to be returned to the United States where some would be given leave, some processed out of service and others would head to the Pacific.[73] The unexpectedly quick end of the Pacific war, with return of troops and even the remains of those killed rather than redeployment becoming the focus, greater traffic burdens than during the war itself became the problem.[74] The ports had the responsibility to process units for inactivation and on 11 April 1945 a conference was held at NYPOE concerning the major adjustments Atlantic area ports would be required to make.[75]

Accomplishments

The NYPOE was by far the largest of the Army Ports of Embarkation and at the close of 1944, aside from the embarkation camps, controlled piers with berths for 100 oceangoing vessels, 4,895,000 square feet of transit shed space, 5,500,000 square feet of warehouse space and 13,000,000 square feet of open storage and working space.[76] By August 1945 3,172,778 passengers and 37,799,955 measurement tons of cargo had passed through NYPOE with 5,893,199 tons of cargo having passed through its Philadelphia cargo sub-port.[77] With the total for all ports being 7,293,354 passengers and 126,787,875 tons of cargo this put the NYPOE at 44% of all troops and 34% of all cargo passing through Army Ports of Embarkation.[77]

During the war 85 percent of men and material headed to the European theater passed through the NYPOE.[citation needed]

An early extraordinary demand came when an urgent British request came 13 July 1942 for tanks and artillery to counter Rommel after the fall of Tobruk, and a convoy of six fast freighters was loaded at NYPOE with armor and ammunition for Egypt via the Cape of Good Hope.[78] Fifty-two tanks, eighteen self-propelled guns and other supplies were lost when SS Fairport was sunk and NYPOE located replacement armor and ammunition, loaded and dispatched Seatrain Texas within forty-eight hours to sail unescorted and ultimately arrive at Suez in time for the fully assembled cargo to help defend Cairo.[79]

Post war

The New York Port of Embarkation continued operations under the Chief of Transportation with the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation becoming a sub-port effective 31 March 1954.[80] On 28 September 1955 the New York Port of Embarkation was redesignated effective 1 October as the Atlantic Transportation Terminal Command, Brooklyn, headquartered in the Brooklyn Army Base with responsibility for operation of all Army terminal and related activities of the Atlantic coast from those in Canada south to Miami, Florida.[19] By the same order the other Ports of Embarkation and sub-ports were redesignated.[19] The Brooklyn Army Base, a class III sub-installation of the New York Port of Embarkation was separated and designated the Brooklyn Army Terminal.[19] Effective 1 April 1965 the remaining Army facility of the NYPOE, the Brooklyn Army Terminal, along with other such remnant facilities of the old ports of embarkation, were transferred from the Army Material Command to the Military Traffic Management and Terminal Service.[81]

References

Footnotes

Notes

- ^ Wardlow 1999, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e Wardlow 1999, p. 96.

- ^ Wardlow 1999, pp. 95.

- ^ Wardlow 1999, pp. 95–111.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Clay 2011, p. 2126.

- ^ a b c Huston 1966, p. 347.

- ^ a b c Wardlow 1956, p. 375.

- ^ a b c d Wardlow 1999, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b c Wardlow 1956, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 135.

- ^ a b War Department 1944, pp. 17–24.

- ^ War Department 1944, p. 17.

- ^ War Department 1944, pp. 17–19.

- ^ War Department 1944, pp. 20–22.

- ^ War Department 1944, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Huston 1966, p. 345.

- ^ Gillett 2009, pp. 174.

- ^ a b c Huston 1966, p. 346.

- ^ a b c d Department of the Army & (28 September 1955).

- ^ Clay 2011, p. 2143.

- ^ Clay 2011, pp. 2140, 2141, 2147, 2153, 2157.

- ^ a b c d Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.1: 233.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 104, 356.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.1: 234–235.

- ^ a b Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.2: 162.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1999, pp. 96, 99 (table).

- ^ Wardlow 1999, p. 99 (table).

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.2:162.

- ^ Larson 1945, p. 155.

- ^ Larson 1945, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 109–125.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 112, Table 11.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c Huston 1966, p. 508.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1956, p. 127.

- ^ a b c The Sunday Gazette & (5 June 1994), p. G2.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 426.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1999, p. 100 Table 9, note b.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 381 Table 32, 382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brooklyn Daily Eagle & (9 December 1945), p. 49.

- ^ a b c Wardlow 1956, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 424.

- ^ a b c d e Wardlow 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.1: 233–238.

- ^ a b Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.1: 236.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1968, p. v.1: 238.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1968, pp. v.2: 160–166.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1956, p. 378.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 382–384.

- ^ Thiesen 2009.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 382.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 99–100, 107.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1956, p. 56.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 55.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 107.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 106, 108.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1956, p. 103.

- ^ a b Hudson 1946, pp. 6–11.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1956, p. 109.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 109, 116.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 114.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 77–79, 82, 109, 168.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1956, p. 116.

- ^ Smith 1956, p. 336.

- ^ Smith 1956, p. 337.

- ^ Smith 1956, pp. 321, 336–337.

- ^ War Department 1944, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Smith 1956, p. 321.

- ^ Smith 1956, pp. 405–416.

- ^ Smith 1956, p. 405.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 168.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 104, 176.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 173.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, p. 167.

- ^ Wardlow 1956, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Wardlow 1999, p. 100.

- ^ a b Wardlow 1999, p. 99.

- ^ Brooklyn Daily Eagle & (9 December 1945), p. 48.

- ^ Brooklyn Daily Eagle & (9 December 1945), pp. 48–49.

- ^ Department of the Army & (24 February 1954).

- ^ Department of the Army & (1 April 1965).

Bibliography

- "An Atlantic Coast Port". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 9 December 1945. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Clay, Steven E. (2011). U. S. Army Order Of Battle 1919–1941 (PDF). Volume 4. The Services: Quartermaster, Medical, Military Police, Signal Corps, Chemical Warfare, And Miscellaneous Organizations, 1919–41. Vol. 4. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 9780984190140. LCCN 2010022326.

- "D-Day embarkation camp recalled in "minimuseum"". The Sunday Gazette. Schenectady, New York: The Daily Gazette. 5 June 1994. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Gillett, Mary C. (2009). The Army Medical Department 1917–1941. Army Historical Series. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 2008053316. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- General Orders No. 14 (PDF), Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 24 February 1954, retrieved 20 November 2014

- General Orders No. 55 (PDF), Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 28 September 1955, retrieved 20 November 2014

- General Orders No. 12 (PDF), Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1 April 1965, retrieved 20 November 2014

- Hudson, Henry W. (1946). The Story of SNAG 56. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Huston, James A. (1966). The Sinews of War: Army Logistics 1775–1953. Army Historical Series. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. p. 346. ISBN 9780160899140. LCCN 66060015. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Larson, Harold (1945). The Army's Cargo Fleet In World War II. Washington, D. C.: Office of the Chief of Transportation, Army Service Forces, U. S. Army.

- Leighton, Richard M; Coakley, Robert W (1968) [1st. Pub. 1955]. The War Department — Global Logistics And Strategy 1940–1943. United States Army In World War II. Vol. 2 vol. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 55060001.

- Smith, Clarence McKittrick (1956). The Technical Services—The Medical Department: Hospitalization And Evacuation, Zone Of Interior. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 55060005.

- Thiesen, William H. (2009). "The El Estero Fire and How the US Coast Guard Helped Save New York Harbor" (PDF). Sea History (Spring 2009). National Maritime Historical Society: 16–20. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Wardlow, Chester (1956). The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training, And Supply. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 55060003. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- Wardlow, Chester (1999). The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Responsibilities, Organization, And Operations. United States Army In World War II. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 99490905. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- War Department (1944). FM55-10 Water Transportation: Oceangoing Vessels (PDF). War Department Field Manual. Washington, DC: United States Department of War. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

External links

- With the Army at Hoboken

- FM55-10, War Department Field Manual, 25 September 1944

- Phillip M. Goldstein. "Military Railroads of the New York Metropolitan Area: Brooklyn Army Terminal". TrainWeb. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Military units and formations of the United States in World War I

- Military units and formations of the United States Army in World War II

- Transportation units and formations of the United States Army

- Military ports

- Ports and harbors of New York (state)

- Ports and harbors of New Jersey

- Military history of New York City

- Military history of New Jersey

- History of transportation in New York City

- Port of New York and New Jersey

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !