Quaternary glaciation

The Quaternary glaciation, also known as the Pleistocene glaciation, is an alternating series of glacial and interglacial periods during the Quaternary period that began 2.58 Ma (million years ago) and is ongoing.[1][2][3] Although geologists describe this entire period up to the present as an "ice age", in popular culture this term usually refers to the most recent glacial period, or to the Pleistocene epoch in general.[4] Since Earth still has polar ice sheets, geologists consider the Quaternary glaciation to be ongoing, though currently in an interglacial period.

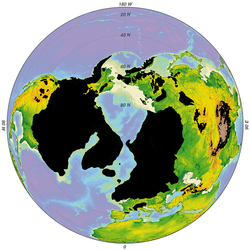

During the Quaternary glaciation, ice sheets appeared, expanding during glacial periods and contracting during interglacial periods. Since the end of the last glacial period, only the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets have survived, while other sheets formed during glacial periods, such as the Laurentide Ice Sheet, have completely melted.

The major effects of the Quaternary glaciation have been the continental erosion of land and the deposition of material; the modification of river systems; the formation of millions of lakes, including the development of pluvial lakes far from the ice margins; changes in sea level; the isostatic adjustment of the Earth's crust; flooding; and abnormal winds. The ice sheets, by raising the albedo (the ratio of solar radiant energy reflected from Earth back into space), generated significant feedback to further cool the climate. These effects have shaped land and ocean environments and biological communities.

Long before the Quaternary glaciation, land-based ice appeared and then disappeared during at least four other ice ages. The Quaternary glaciation can be considered a part of a Late Cenozoic Ice Age that began 33.9 Ma and is ongoing.

Discovery

Evidence for the Quaternary glaciation was first understood in the 18th and 19th centuries as part of the scientific revolution. Over the last century, extensive field observations have provided evidence that continental glaciers covered large parts of Europe, North America, and Siberia. Maps of glacial features were compiled after many years of fieldwork by hundreds of geologists who mapped the location and orientation of drumlins, eskers, moraines, striations, and glacial stream channels to reveal the extent of the ice sheets, the direction of their flow, and the systems of meltwater channels. They also allowed scientists to decipher a history of multiple advances and retreats of the ice. Even before the theory of worldwide glaciation was generally accepted, many observers recognized that more than a single advance and retreat of the ice had occurred.

Description

To geologists, an ice age is defined by the presence of large amounts of land-based ice. Prior to the Quaternary glaciation, land-based ice formed during at least four earlier geologic periods: the late Paleozoic (360–260 Ma), Andean-Saharan (450–420 Ma), Cryogenian (720–635 Ma) and Huronian (2,400–2,100 Ma).[5][6]

Within the Quaternary ice age, there were also periodic fluctuations of the total volume of land ice, the sea level, and global temperatures. During the colder episodes (referred to as glacial periods or glacials) large ice sheets at least 4 km (2.5 mi) thick at their maximum covered parts of Europe, North America, and Siberia. The shorter warm intervals between glacials, when continental glaciers retreated, are referred to as interglacials. These are evidenced by buried soil profiles, peat beds, and lake and stream deposits separating the unsorted, unstratified deposits of glacial debris.

Initially the glacial/interglacial cycle length was about 41,000 years, but following the Mid-Pleistocene Transition about 1 Ma, it slowed to about 100,000 years, as evidenced most clearly by ice cores for the past 800,000 years and marine sediment cores for the earlier period. Over the past 740,000 years there have been eight glacial cycles.[7]

The entire Quaternary period, starting 2.58 Ma, is referred to as an ice age because at least one permanent large ice sheet—the Antarctic ice sheet—has existed continuously. There is uncertainty over how much of Greenland was covered by ice during each interglacial. Currently, Earth is in an interglacial period, the Holocene epoch beginning 11,700 years ago; this has caused the ice sheets from the Last Glacial Period to slowly melt. The remaining glaciers, now occupying about 10% of the world's land surface, cover Greenland, Antarctica and some mountainous regions. During the glacial periods, the present (i.e., interglacial) hydrologic system was completely interrupted throughout large areas of the world and was considerably modified in others. The volume of ice on land resulted in a sea level about 120 metres (394 ft) lower than present.

Causes

Earth's history of glaciation is a product of the internal variability of Earth's climate system (e.g., ocean currents, carbon cycle), interacting with external forcing by phenomena outside the climate system (e.g., changes in Earth's orbit, volcanism, and changes in solar output).[8]

Astronomical cycles

The role of Earth's orbital changes in controlling climate was first advanced by James Croll in the late 19th century.[9] Later, the Serbian geophysicist Milutin Milanković elaborated on the theory and calculated that these irregularities in Earth's orbit could cause the climatic cycles now known as Milankovitch cycles.[10] They are the result of the additive behavior of several types of cyclical changes in Earth's orbital properties.

Firstly, changes in the orbital eccentricity of Earth occur on a cycle of about 100,000 years.[11] Secondly, the inclination or tilt of Earth's axis varies between 22° and 24.5° in a cycle 41,000 years long.[11] The tilt of Earth's axis is responsible for the seasons; the greater the tilt, the greater the contrast between summer and winter temperatures. Thirdly, precession of the equinoxes, or wobbles in the Earth's rotation axis, have a periodicity of 26,000 years. According to the Milankovitch theory, these factors cause a periodic cooling of Earth, with the coldest part in the cycle occurring about every 40,000 years. The main effect of the Milankovitch cycles is to change the contrast between the seasons, not the annual amount of solar heat Earth receives. The result is less ice melting than accumulating, and glaciers build up.

Milankovitch worked out the ideas of climatic cycles in the 1920s and 1930s, but it was not until the 1970s that a sufficiently long and detailed chronology of the Quaternary temperature changes was worked out to test the theory adequately.[12] Studies of deep-sea cores and their fossils indicate that the fluctuation of climate during the last few hundred thousand years is remarkably close to that predicted by Milankovitch.

Atmospheric composition

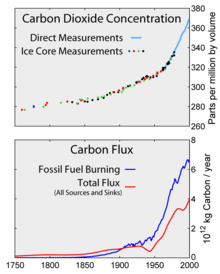

One theory holds that decreases in atmospheric CO

2, an important greenhouse gas, started the long-term cooling trend that eventually led to the formation of continental ice sheets in the Arctic.[13] Geological evidence indicates a decrease of more than 90% in atmospheric CO2 since the middle of the Mesozoic Era.[14] An analysis of CO2 reconstructions from alkenone records shows that CO2 in the atmosphere declined before and during Antarctic glaciation, and supports a substantial CO2 decrease as the primary cause of Antarctic glaciation.[15] Decreasing carbon dioxide levels during the late Pliocene may have contributed substantially to global cooling and the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation.[16][17] This decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations may have come about by way of the decreasing ventilation of deep water in the Southern Ocean.[18]

CO2 levels also play an important role in the transitions between interglacials and glacials. High CO2 contents correspond to warm interglacial periods, and low CO2 to glacial periods. However, studies indicate that CO

2 may not be the primary cause of the interglacial-glacial transitions, but instead acts as a feedback. The explanation for this observed CO

2 variation "remains a difficult attribution problem".[19]

Plate tectonics and ocean currents

An important component in the development of long-term ice ages is the positions of the continents.[20] These can control the circulation of the oceans and the atmosphere, affecting how ocean currents carry heat to high latitudes. Throughout most of geologic time, the North Pole appears to have been in a broad, open ocean that allowed major ocean currents to move unabated. Equatorial waters flowed into the polar regions, warming them. This produced mild, uniform climates that persisted throughout most of geologic time.

But during the Cenozoic Era, the large North American and South American continental plates drifted westward from the Eurasian Plate. This interlocked with the development of the Atlantic Ocean, running north–south, with the North Pole in the small, nearly landlocked basin of the Arctic Ocean. The Drake Passage opened 33.9 million years ago (the Eocene-Oligocene transition), severing Antarctica from South America. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current could then flow through it, isolating Antarctica from warm waters and triggering the formation of its huge ice sheets. The weakening of the North Atlantic Current (NAC) around 3.65 to 3.5 million years ago resulted in cooling and freshening of the Arctic Ocean, nurturing the development of Arctic sea ice and preconditioning the formation of continental glaciers later in the Pliocene.[21] A dinoflagellate cyst turnover in the eastern North Atlantic approximately ~2.60 Ma, during MIS 104, has been cited as evidence that the NAC shifted significantly to the south at this time, causing an abrupt cooling of the North Sea and northwestern Europe by reducing heat transport to high latitude waters of the North Atlantic.[22] The Isthmus of Panama developed at a convergent plate margin about 2.6 million years ago and further separated oceanic circulation, closing the last strait, outside the polar regions, that had connected the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.[23] This increased poleward salt and heat transport, strengthening the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation, which supplied enough moisture to Arctic latitudes to initiate the Northern Hemisphere glaciation.[24][25] The change in the biogeography of the nannofossil Coccolithus pelagicus around 2.74 Ma is believed to reflect this onset of glaciation.[26] However, model simulations suggest reduced ice volume due to increased ablation at the edge of the ice sheet under warmer conditions.[27]

Collapse of permanent El Niño

A permanent El Niño state existed in the early-mid-Pliocene. Warmer temperature in the eastern equatorial Pacific caused an increased water vapor greenhouse effect and reduced the area covered by highly reflective stratus clouds, thus decreasing the albedo of the planet. Propagation of the El Niño effect through planetary waves may have warmed the polar region and delayed the onset of glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere. Therefore, the appearance of cold surface water in the east equatorial Pacific around 3 million years ago may have contributed to global cooling and modified the global climate’s response to Milankovitch cycles.[28]

Rise of mountains

The elevation of continental surface, often as mountain formation, is thought to have contributed to cause the Quaternary glaciation. The gradual movement of the bulk of Earth's landmasses away from the tropics in addition to increased mountain formation in the Late Cenozoic meant more land at high altitude and high latitude, favouring the formation of glaciers.[29] For example, the Greenland ice sheet formed in connection to the uplift of the west Greenland and east Greenland uplands in two phases, 10 and 5 Ma, respectively. These mountains constitute passive continental margins.[30] Uplift of the Rocky Mountains and Greenland’s west coast has been speculated to have cooled the climate due to jet stream deflection and increased snowfall due to higher surface elevation.[31] Computer models show that such uplift would have enabled glaciation through increased orographic precipitation and cooling of surface temperatures.[30] For the Andes it is known that the Principal Cordillera had risen to heights that allowed for the development of valley glaciers about 1 Ma.[32]

Effects

The presence of so much ice upon the continents had a profound effect upon almost every aspect of Earth's hydrologic system. Most obvious are the spectacular mountain scenery and other continental landscapes fashioned both by glacial erosion and deposition instead of running water. Entirely new landscapes covering millions of square kilometers were formed in a relatively short period of geologic time. In addition, the vast bodies of glacial ice affected Earth well beyond the glacier margins. Directly or indirectly, the effects of glaciation were felt in every part of the world.

Lakes

The Quaternary glaciation produced more lakes than all other geologic processes combined. The reason is that a continental glacier completely disrupts the preglacial drainage system. The surface over which the glacier moved was scoured and eroded by the ice, leaving many closed, undrained depressions in the bedrock. These depressions filled with water and became lakes.

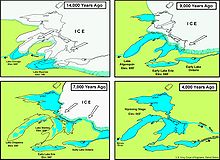

Very large lakes were formed along the glacial margins. The ice on both North America and Europe was about 3,000 m (10,000 ft) thick near the centers of maximum accumulation, but it tapered toward the glacier margins. Ice weight caused crustal subsidence, which was greatest beneath the thickest accumulation of ice. As the ice melted, rebound of the crust lagged behind, producing a regional slope toward the ice. This slope formed basins that have lasted for thousands of years. These basins became lakes or were invaded by the ocean. The Baltic Sea[33][34] and the Great Lakes of North America[35] were formed primarily in this way.[dubious – discuss]

The numerous lakes of the Canadian Shield, Sweden, and Finland are thought to have originated at least partly from glaciers' selective erosion of weathered bedrock.[36][37]

Pluvial lakes

The climatic conditions that cause glaciation had an indirect effect on arid and semiarid regions far removed from the large ice sheets. The increased precipitation that fed the glaciers also increased the runoff of major rivers and intermittent streams, resulting in the growth and development of large pluvial lakes. Most pluvial lakes developed in relatively arid regions where there typically was insufficient rain to establish a drainage system leading to the sea. Instead, stream runoff flowed into closed basins and formed playa lakes. With increased rainfall, the playa lakes enlarged and overflowed. Pluvial lakes were most extensive during glacial periods. During interglacial stages, with less rain, the pluvial lakes shrank to form small salt flats.

Isostatic adjustment

Major isostatic adjustments of the lithosphere during the Quaternary glaciation were caused by the weight of the ice, which depressed the continents. In Canada, a large area around Hudson Bay was depressed below (modern) sea level, as was the area in Europe around the Baltic Sea. The land has been rebounding from these depressions since the ice melted. Some of these isostatic movements triggered large earthquakes in Scandinavia about 9,000 years ago. These earthquakes are unique in that they are not associated with plate tectonics.

Studies have shown that the uplift has taken place in two distinct stages. The initial uplift following deglaciation was rapid (called "elastic"), and took place as the ice was being unloaded. After this "elastic" phase, uplift proceed by "slow viscous flow" so the rate decreased exponentially after that. Today, typical uplift rates are of the order of 1 cm per year or less, except in areas of North America, especially Alaska, where the rate of uplift is 2.54 cm per year (1 inch or more).[38] In northern Europe, this is clearly shown by the GPS data obtained by the BIFROST GPS network.[39] Studies suggest that rebound will continue for at least another 10,000 years. The total uplift from the end of deglaciation depends on the local ice load and could be several hundred meters near the center of rebound.

Winds

The presence of ice over so much of the continents greatly modified patterns of atmospheric circulation. Winds near the glacial margins were strong and persistent because of the abundance of dense, cold air coming off the glacier fields. These winds picked up and transported large quantities of loose, fine-grained sediment brought down by the glaciers. This dust accumulated as loess (wind-blown silt), forming irregular blankets over much of the Missouri River valley, central Europe, and northern China.

Sand dunes were much more widespread and active in many areas during the early Quaternary period. A good example is the Sand Hills region in Nebraska which covers an area of about 60,000 km2 (23,166 sq mi).[40] This region was a large, active dune field during the Pleistocene epoch but today is largely stabilized by grass cover.[41][42]

Ocean currents

Thick glaciers were heavy enough to reach the sea bottom in several important areas, which blocked the passage of ocean water and affected ocean currents. In addition to these direct effects, it also caused feedback effects, as ocean currents contribute to global heat transfer.

Gold deposits

Moraines and till deposited by Quaternary glaciers have contributed to the formation of valuable placer deposits of gold. This is the case of southernmost Chile where reworking of Quaternary moraines have concentrated gold offshore.[43]

Records of prior glaciation

Glaciation has been a rare event in Earth's history,[44] but there is evidence of widespread glaciation during the late Paleozoic Era (300 to 200 Ma) and the late Precambrian (i.e., the Neoproterozoic Era, 800 to 600 Ma).[45] Before the current ice age, which began 2 to 3 Ma, Earth's climate was typically mild and uniform for long periods of time. This climatic history is implied by the types of fossil plants and animals and by the characteristics of sediments preserved in the stratigraphic record.[46] There are, however, widespread glacial deposits, recording several major periods of ancient glaciation in various parts of the geologic record. Such evidence suggests major periods of glaciation prior to the current Quaternary glaciation.

One of the best documented records of pre-Quaternary glaciation, called the Karoo Ice Age, is found in the late Paleozoic rocks in South Africa, India, South America, Antarctica, and Australia. Exposures of ancient glacial deposits are numerous in these areas. Deposits of even older glacial sediment exist on every continent except South America. These indicate that two other periods of widespread glaciation occurred during the late Precambrian, producing the Snowball Earth during the Cryogenian period.[47]

Next glacial period

2 since the Industrial Revolution

The warming trend following the Last Glacial Maximum, since about 20,000 years ago, has resulted in a sea level rise by about 121 metres (397 ft). This warming trend subsided about 6,000 years ago, and sea level has been comparatively stable since the Neolithic. The present interglacial period (the Holocene climatic optimum) has been stable and warm compared to the preceding ones, which were interrupted by numerous cold spells lasting hundreds of years. This stability might have allowed the Neolithic Revolution and by extension human civilization.[48]

Based on orbital models, the cooling trend initiated about 6,000 years ago will continue for another 23,000 years.[49] Slight changes in the Earth's orbital parameters may, however, indicate that, even without any human contribution, there will not be another glacial period for the next 50,000 years.[50] It is possible that the current cooling trend might be interrupted by an interstadial phase (a warmer period) in about 60,000 years, with the next glacial maximum reached only in about 100,000 years.[51]

Based on past estimates for interglacial durations of about 10,000 years, in the 1970s there was some concern that the next glacial period would be imminent. However, slight changes in the eccentricity of Earth's orbit around the Sun suggest a lengthy interglacial period lasting about another 50,000 years.[52] Other models, based on periodic variations in solar output, give a different projection of the start of the next glacial period at around 10,000 years from now.[53] Additionally, human impact is now seen as possibly extending what would already be an unusually long warm period. Projection of the timeline for the next glacial maximum depend crucially on the amount of CO

2 in the atmosphere. Models assuming increased CO

2 levels at 750 parts per million (ppm; current levels are at 417 ppm[54]) have estimated the persistence of the current interglacial period for another 50,000 years.[55] However, more recent studies concluded that the amount of heat trapping gases emitted into Earth's oceans and atmosphere will prevent the next glacial (ice age), which otherwise would begin in around 50,000 years, and likely more glacial cycles.[56][57]

References

- ^ Lorens, L.; Hilgen, F.; Shackelton, N.J.; Laskar, J.; Wilson, D. (2004). "Part III Geological Periods: 21 The Neogene Period". In Gradstein, Felix M.; Ogg, James G.; Smith, Alan G. (eds.). A Geologic Time Scale 2004. Cambridge University Press. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-521-78673-7.

- ^ Ehlers, Jürgen; Gibbard, Philip (2011). "Quaternary Glaciation". Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 873–882. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2642-2_423. ISBN 978-90-481-2641-5.

- ^ Berger, A.; Loutre, M.F. (2000). "CO2 And Astronomical Forcing of the Late Quaternary". Proceedings of the 1st Solar and Space Weather Euroconference, 25-29 September 2000. Vol. 463. ESA Publications Division. p. 155. Bibcode:2000ESASP.463..155B. ISBN 9290926937.

- ^ "Glossary of Technical Terms Related to the Ice Age Floods". Ice Age Floods Institute. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Lockwood, J.G.; van Zinderen-Bakker, E. M. (November 1979). "The Antarctic Ice-Sheet: Regulator of Global Climates?: Review". The Geographical Journal. 145 (3): 469–471. doi:10.2307/633219. JSTOR 633219.

- ^ Warren, John K. (2006). Evaporites: sediments, resources and hydrocarbons. Birkhäuser. p. 289. ISBN 978-3-540-26011-0.

- ^ Augustin, Laurent; et al. (2004). "Eight glacial cycles from an Antarctic ice core". Nature. 429 (6992): 623–8. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..623A. doi:10.1038/nature02599. PMID 15190344.

- ^ "Why were there Ice Ages?". Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ Discovery of the Ice Age

- ^ EO Library: Milutin Milankovitch Archived December 10, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Why do glaciations occur?

- ^ EO Library: Milutin Milankovitch Page 3

- ^ Bartoli, Greta; Hönisch, Bärbel; Zeebe, Richard E. (16 November 2011). "Atmospheric CO2 decline during the Pliocene intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 26 (4): 1–14. Bibcode:2011PalOc..26.4213B. doi:10.1029/2010PA002055.

- ^ Fletcher, Benjamin J.; Brentnall, Stuart J.; Anderson, Clive W.; Berner, Robert A.; Beerling, David J. (2008). "Atmospheric carbon dioxide linked with Mesozoic and early Cenozoic climate change". Nature Geoscience. 1 (1): 43–48. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1...43F. doi:10.1038/ngeo.2007.29.

- ^ Pagani, Mark; Huber, Matthew; Liu, Zhonghui; Bohaty, Steven M.; Henderiks, Jorijntje; Sijp, Willem; Krishnan, Srinath; DeConto, Robert M. (2011). "The Role of Carbon Dioxide During the Onset of Antarctic Glaciation". Science. 334 (6060): 1261–4. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1261P. doi:10.1126/science.1203909. PMID 22144622. S2CID 206533232.

- ^ Bartoli, Gretta; Hönisch, Bärbel; Zeebe, Richard E. (16 November 2011). "Atmospheric CO2 decline during the Pliocene intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 26 (4): 1–14. Bibcode:2011PalOc..26.4213B. doi:10.1029/2010PA002055.

- ^ Lunt, D. J.; Foster, G. L.; Haywood, A. M.; Stone, E. J. (2008). "Late Pliocene Greenland glaciation controlled by a decline in atmospheric CO2 levels". Nature. 454 (7208): 1102–1105. Bibcode:2008Natur.454.1102L. doi:10.1038/nature07223. PMID 18756254. S2CID 4364843.

- ^ Hodell, David A.; Venz-Curtis, Kathryn A. (6 September 2006). "Late Neogene history of deepwater ventilation in the Southern Ocean". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 7 (9): 1–16. Bibcode:2006GGG.....7.9001H. doi:10.1029/2005GC001211. S2CID 129085686.

- ^ Joos, Fortunat; Prentice, I. Colin (2004). "A Paleo-Perspective on Changes in Atmospheric CO2 and Climate" (PDF). The Global Carbon Cycle: Integrating Humans, Climate, and the Natural World. Scope. Vol. 62. Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 165–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ Glaciers and Glaciation Archived August 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kalas, Cyrus; Khélifi, Nabil; Bahr, André; Naafs, B. D. A.; Nürnberg, Dirk; Herrle, Jens O. (January 2020). "Did North Atlantic cooling and freshening from 3.65–3.5 Ma precondition Northern Hemisphere ice sheet growth?". Global and Planetary Change. 185: 103085. Bibcode:2020GPC...18503085K. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.103085. hdl:1983/f1d7878d-a7cb-49b5-8e33-7bfc6fb3cb1c. S2CID 213769471.

- ^ Hennissen, Jan A. I.; Head, Martin J.; De Schepper, Stijn; Groeneveld, Jeroen (15 May 2014). "Palynological evidence for a southward shift of the North Atlantic Current at ~2.6 Ma during the intensification of late Cenozoic Northern Hemisphere glaciation". Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology. 29 (6): 564–580. Bibcode:2014PalOc..29..564H. doi:10.1002/2013PA002543.

- ^ EO Newsroom: New Images – Panama: Isthmus that Changed the World Archived August 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bartoli, G.; Sarnthein, M.; Weinelt, M.; Erlenkeuser, H.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Lea, D. W. (30 August 2005). "Final closure of Panama and the onset of northern hemisphere glaciation". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 237 (1): 33–44. Bibcode:2005E&PSL.237...33B. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.06.020. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Haug, G. H.; Tiedemann, R. (1998). "Effect of the formation of the Isthmus of Panama on Atlantic Ocean thermohaline circulation". Nature. 393 (6686): 673–676. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..673H. doi:10.1038/31447. S2CID 4421505.

- ^ Sato, Tokiyuki; Yuguchi, Shiho; Takayama, Toshiaki; Kameo, Koji (August 2004). "Drastic change in the geographical distribution of the cold-water nannofossil Coccolithus pelagicus (Wallich) Schiller at 2.74 Ma in the late Pliocene, with special reference to glaciation in the Arctic Ocean". Marine Micropaleontology. 52 (1–4): 181–193. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2004.05.003. Retrieved 30 October 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Lunt, D. J.; Foster, G. L.; Haywood, A. M.; Stone, E. J. (2008). "Late Pliocene Greenland glaciation controlled by a decline in atmospheric CO2 levels". Nature. 454 (7208): 1102–1105. Bibcode:2008Natur.454.1102L. doi:10.1038/nature07223. PMID 18756254. S2CID 4364843.

- ^ Philander, S. G.; Fedorov, A. V. (2003). "Role of tropics in changing the response to Milankovich forcing some three million years ago". Paleoceanography. 18 (2): 1045. Bibcode:2003PalOc..18.1045P. doi:10.1029/2002PA000837.

- ^ Flint, Richard Foster (1971). Glacial and Quaternary Geology. John Wiley and Sons. p. 22.

- ^ a b Solgaard, Anne M.; Bonow, Johan M.; Langen, Peter L.; Japsen, Peter; Hvidberg, Christine (2013). "Mountain building and the initiation of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 392: 161–176. Bibcode:2013PPP...392..161S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.09.019.

- ^ Lunt, D. J.; Foster, G. L.; Haywood, A. M.; Stone, E. J. (2008). "Late Pliocene Greenland glaciation controlled by a decline in atmospheric CO2 levels". Nature. 454 (7208): 1102–1105. Bibcode:2008Natur.454.1102L. doi:10.1038/nature07223. PMID 18756254. S2CID 4364843.

- ^ Charrier, Reynaldo; Iturrizaga, Lafasam; Charretier, Sebastién; Regard, Vincent (2019). "Geomorphologic and Glacial Evolution of the Cachapoal and southern Maipo catchments in the Andean Principal Cordillera, Central Chile (34°-35º S)". Andean Geology. 46 (2): 240–278. doi:10.5027/andgeoV46n2-3108. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Tikkanen, Matti; Oksanen, Juha (2002). "Late Weichselian and Holocene shore displacement history of the Baltic Sea in Finland". Fennia. 180 (1–2). Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ Polish Geological Institute Archived March 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CVO Website – Glaciations and Ice Sheets

- ^ Lidmar-Bergström, K.; Olsson, S.; Roaldset, E. (1999). "Relief features and palaeoweathering remnants in formerly glaciated Scandinavian basement areas". In Thiry, Médard; Simon-Coinçon, Régine (eds.). Palaeoweathering, Palaeosurfaces and Related Continental Deposits. Special publication of the International Association of Sedimentologists. Vol. 27. Blackwell. pp. 275–301. ISBN 0-632-05311-9.

- ^ Lindberg, Johan (April 4, 2016). "berggrund och ytformer". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish). Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ Actual observations from Haines, Alaska

- ^ Johansson, J.M.; Davis, J.L.; Scherneck, H.-G.; Milne, G.A.; Vermeer, M.; Mitrovica, J.X.; Bennett, R.A.; Jonsson, B.; Elgered, G.; Elósegui, P.; Koivula, H.; Poutanen, M.; Rönnäng, B.O.; Shapiro, I.I. (2002). "Continuous GPS measurements of postglacial adjustment in Fennoscandia 1. Geodetic results". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 107 (B8): 2157. Bibcode:2002JGRB..107.2157J. doi:10.1029/2001JB000400.[permanent dead link]

- ^ EO Newsroom: New Images – Sand Hills, Nebraska Archived August 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ LiveScience.com Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nebraska Sand Hills Archived 2007-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ García, Marcelo; Correa, Jorge; Maksaev, Víctor; Townley, Brian (2020). "Potential mineral resources of the Chilean offshore: an overview". Andean Geology. 47 (1): 1–13. doi:10.5027/andgeov47n1-3260.

- ^ "Ice Ages- Illinois State Museum". Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ "When have Ice Ages occurred?". Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ Our Changing Continent

- ^ Geotimes – April 2003 – Snowball Earth

- ^ Richerson, Peter J.; Robert Boyd; Robert L. Bettinger (2001). "Was agriculture impossible during the Pleistocene but mandatory during the Holocene? A climate change hypothesis" (PDF). American Antiquity. 66 (3): 387–411. doi:10.2307/2694241. JSTOR 2694241. S2CID 163474968. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ J Imbrie; J Z Imbrie (1980). "Modeling the Climatic Response to Orbital Variations". Science. 207 (4434): 943–953. Bibcode:1980Sci...207..943I. doi:10.1126/science.207.4434.943. PMID 17830447. S2CID 7317540.

- ^ Berger A, Loutre MF (2002). "Climate: An exceptionally long interglacial ahead?". Science. 297 (5585): 1287–8. doi:10.1126/science.1076120. PMID 12193773. S2CID 128923481. "Berger and Loutre argue in their Perspective that with or without human perturbations, the current warm climate may last another 50,000 years. The reason is a minimum in the eccentricity of Earth's orbit around the Sun."

- ^ "NOAA Paleoclimatology Program – Orbital Variations and Milankovitch Theory". A. Ganopolski; R. Winkelmann; H. J. Schellnhuber (2016). "Critical insolation–CO2 relation for diagnosing past and future glacial inception". Nature. 529 (7585): 200–203. Bibcode:2016Natur.529..200G. doi:10.1038/nature16494. PMID 26762457. S2CID 4466220. M. F. Loutre, A. Berger, "Future Climatic Changes: Are We Entering an Exceptionally Long Interglacial?", Climatic Change 46 (2000), 61-90.

- ^ Berger, A.; Loutre, M.F. (2002-08-23). "An Exceptionally Long Interglacial Ahead?" (PDF). Science. 297 (5585): 1287–8. doi:10.1126/science.1076120. PMID 12193773. S2CID 128923481.[dead link]

- ^ Perry, Charles A.; Hsu, Kenneth J. (24 October 2000). "Geophysical, archaeological, and historical evidence support a solar-output model for climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (23): 12433–12438. doi:10.1073/pnas.230423297. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 18780. PMID 11050181. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Tans, Pieter. "Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide – Mauna Loa". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-05-06.

- ^ Christiansen, Eric (2014). Dynamic Earth. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 441. ISBN 9781449659028.

- ^ "Global Warming Good News: No More Ice Ages". LiveScience. 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ "Human-made climate change suppresses the next ice age". Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. 2016.

External links

![]() The dictionary definition of glaciation at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of glaciation at Wiktionary

- Glaciers and Glaciation

- Pleistocene Glaciation and Diversion of the Missouri River in Northern Montana Archived 2012-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Clark, Peter U.; Bartlein, Patrick J. (1995). "Correlation of late Pleistocene glaciation in the western United States with North Atlantic Heinrich events". Geology. 23 (4): 483–6. Bibcode:1995Geo....23..483C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0483:COLPGI>2.3.CO;2.

- Pielou, E.C. (2008). After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-66809-3.

- Alaska's Glacier and Icefields

- Pleistocene glaciations at the Wayback Machine (archived 7 February 2012) (the last 2 million years)

- IPCC's Palaeoclimate(pdf) Archived 2013-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Causes

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !