Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

| |

| Nicknames | Pendleton Act |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 47th United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Statutes at Large | ch. 27, 22 Stat. 403 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal government should be awarded on the basis of merit instead of political patronage.

By the late 1820s, American politics operated on the spoils system, a political patronage practice in which officeholders awarded their allies with government jobs in return for financial and political support. Proponents of the spoils system were successful at blocking meaningful civil service reform until the assassination of President James A. Garfield in 1881. The 47th Congress passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act during its lame duck session and President Chester A. Arthur, himself a former spoilsman, signed the bill into law.

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act provided for the selection of some government employees by competitive exams, rather than ties to politicians or political affiliation. It also made it illegal to fire or demote these government officials for political reasons and created the United States Civil Service Commission to enforce the merit system. The act initially only applied to about ten percent of federal employees, but it now covers most federal employees. As a result of the court case Luévano v. Campbell, most federal government employees are no longer hired by means of competitive examinations.

Background

Since the presidency of Andrew Jackson, presidents had increasingly made political appointments on the basis of political support rather than on the basis of merit, in a practice known as the spoils system. In return for appointments, these appointees were charged with raising campaign funds and bolstering the popularity of the president and the party in their communities. The success of the spoils system helped ensure the dominance of both the Democratic Party in the period before the American Civil War and the Republican Party in the period after the Civil War. Patronage became a key issue in elections, as many partisans in both major parties were more concerned about control over political appointments than they were about policy issues.[1]

During the Civil War, Senator Charles Sumner introduced the first major civil service reform bill, calling for the use of competitive exams to determine political appointments. Sumner's bill failed to pass Congress, and in subsequent years several other civil service reform bills were defeated even as the public became increasingly concerned about public corruption.[2] After taking office in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes established a special cabinet committee charged with drawing up new rules for federal appointments.[3] Hayes's efforts for reform brought him into conflict with the Stalwart, or pro-spoils, branch of the Republican party, led by Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York.[4] With Congress unwilling to take action on civil service reform, Hayes issued an executive order that forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics.[5]

According to historian Eric Foner, the advocacy of civil service reform was recognized by blacks as an effort that would stifle their economic mobility and prevent "the whole colored population" from holding public office.[6]

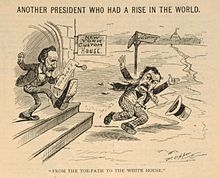

Chester Arthur, Collector of the Port of New York, and his partisan subordinates Alonzo B. Cornell and George H. Sharpe, all Conkling supporters, obstinately refused to obey the president's order.[5] In September 1877, Hayes demanded the three men's resignations, which they refused to give.[7] Hayes was obliged to wait until July 1878 when, during a Congressional recess, he sacked Arthur and Cornell and replaced them with recess appointments.[8] Despite opposition from Conkling, both of Hayes's nominees were confirmed by the Senate, giving Hayes his most significant civil service reform victory.[9] For the remainder of his term, Hayes pressed Congress to enact permanent reform legislation and restore the dormant United States Civil Service Commission, even using his last annual message to Congress in 1880 to appeal for reform.[10]

Provisions

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act provided for selection of some government employees by competitive exams rather than ties to politicians, and made it illegal to fire or demote some government officials for political reasons.[11] The act initially applied only to ten percent of federal jobs, but it allowed the president to expand the number of federal employees covered by the act.[12] Within five years of the passage of the law, half of federal appointments outside of the United States Postal Service were covered by the act.[13]

The law also created the United States Civil Service Commission to oversee civil service examinations and outlawed the use of "assessments," fees that political appointees were expected to pay to their respective political parties as the price for their appointments.[14] These assessments had made up a majority of political contributions in the era following Reconstruction.[15]

Legislative history

In 1880, Democratic Senator George H. Pendleton of Ohio introduced legislation to require the selection of civil servants based on merit as determined by an examination, but the measure failed to pass.[16] Pendleton's bill was largely based on reforms proposed by the Jay Commission, which Hayes had assigned to investigate the Port of New York.[17] It also expanded similar civil service reforms attempted by President Franklin Pierce 30 years earlier.

Hayes did not seek a second term as president, and was succeeded by fellow Republican James A. Garfield, who won the 1880 presidential election on a ticket with former Port Collector Chester A. Arthur. In 1881, President Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau, who believed that he had not received an appointment by Garfield because of his own affiliation with the Stalwarts.[18] Garfield died on September 19, 1881, and was succeeded by Vice President Arthur.[19] Many worried about how Arthur would act as president; the New York Times, which had supported Arthur earlier in his career, wrote "Arthur is about the last man who would be considered eligible for the position."[20]

Garfield's assassination by a deranged office seeker amplified the public demand for reform.[21] Civil service reformers established the National Civil Service Reform League and undertook a major public campaign for reform, arguing that the spoils system had played a major role in the assassination of Garfield.[22] In President Arthur's first annual address to Congress, Arthur requested civil service reform legislation, and Pendleton again introduced his bill, which again did not pass.[16] Democrats, campaigning on the reform issue, won control of the House of Representatives in the 1882 congressional elections.[23]

The party's disastrous performance in the 1882 elections helped convince many Republicans to support the civil service reform during the 1882 lame-duck session of Congress.[17] The election results were seen as a public mandate for civil service reform, but many Republicans also wanted to pass a bill so that they could craft the legislation before losing control of Congress, allowing the party to take credit for the bill and to protect Republican officeholders from dismissal.[24] The Senate approved Pendleton's bill, 38–5, and the House soon concurred by a vote of 155–47.[25] Nearly all congressional opposition to the Pendleton bill came from Democrats, though a majority of Democrats in each chamber of Congress voted for the bill.[26] A mere seven U.S. representatives constituted the Republican opposition towards the Pendleton Act: Benjamin F. Marsh, James S. Robinson, Robert Smalls, William Robert Moore, John R. Thomas, George W. Steele, and Orlando Hubbs.[27] Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act into law on January 16, 1883.[25]

Aftermath

To the surprise of his critics, Arthur acted quickly to appoint the members of the newly created Civil Service Commission, naming reformers Dorman Bridgman Eaton, John Milton Gregory, and Leroy D. Thoman as commissioners.[12] The commission issued its first rules in May 1883; by 1884, half of all postal officials and three-quarters of the Customs Service jobs were to be awarded by merit.[28] During his first term, President Grover Cleveland expanded the number of federal positions subject to the merit system from 16,000 to 27,000. Partly due to Cleveland's efforts, between 1885 and 1897, the percentage of federal employees protected by the Pendleton Act would rise from twelve percent to approximately forty percent.[29] Under subsequent legislation, about 90% of federal employees are covered by the merit system.[30][31]

In the short term, however, the act largely failed to achieve the stated objectives of its supporters. As long as candidates passed the newly created exams, the bureau and division chiefs were left with free reign to appoint whomever they wished to the positions. The patronage system had not been eliminated, it had simply moved the power created by this system to these chiefs.[13] The act also largely failed to accomplish the goal of stopping the practice of bureaucratic officials being dismissed and replaced after each election along partisan lines. Though the act prevented new presidents from directly dismissing officials whenever they wished, the new system only protected officials for a given "term", which most often ran for four years (the same length as a single presidential term). Presidents would simply wait for these terms to expire and then appoint new officials along partisan lines, with a net result of officials only holding their positions a few months longer than they previously would under the system of arbitrary dismissals.[32]

The law also caused major changes in campaign finance. Prior to the act, political parties often acquired much of their funds through taking a percentage of the fees earned by officials they appointed to federal offices. With such officials being prohibited by the act from contributing to political campaigns, parties were forced to look for new sources of campaign funds, such as wealthy donors.[33]

Congress passed the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 as a major update to the Pendleton Act. The Civil Service Commission was abolished and its functions were replaced by the Office of Personnel Management, the Merit Systems Protection Board, and the Federal Labor Relations Authority. The 1978 law created the Senior Executive Service for top managers within the civil service system, and established the right of civil servants to unionize and arbitrate.[34][35]

In January 1981, the Jimmy Carter administration settled the court case Luévano v. Campbell, which alleged the Professional and Administrative Careers Examination (PACE) was racially discriminatory as a result of the lower average scores and pass rates achieved by Black and Hispanic test takers. As a result of this settlement agreement, PACE, the main entry-level test for candidates seeking positions in the federal government’s executive branch, was scrapped.[36] It has not been replaced by a similar general exam, although attempts at replacement exams have been made. The system which replaced the general PACE exam has been criticized as instituting a system of racial quotas, although changes to the settlement agreement under the Ronald Reagan administration removed explicit quotas, and these changes "raised serious questions about the ability of the government to recruit a quality workforce while reducing adverse impact", according to Professor Carolyn Ban.[37][38]

In October 2020 President Donald Trump by Executive Order 13957 created a Schedule F classification in the excepted service of the United States federal civil service for policy-making positions, which was criticized by Professor Donald Kettl as violating the spirit of the Pendleton Act.[39] Shortly after taking office in January 2021, President Joe Biden rescinded Executive Order 13957.[40][31]

See also

References

- ^ Theriault, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 54–55, 60.

- ^ Paul, p. 71.

- ^ Davison, p. 164–165.

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, pp. 322–325; Davison, pp. 164–165; Trefousse, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p. 507. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 353–355; Trefousse, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 382–384; Barnard, p. 456.

- ^ Paul, pp. 73–74.

- ^ "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, pp. 325–327; Doenecke, pp. 102–104.

- ^ a b White 2017, p. 465.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 104–107.

- ^ Theriault, p. 52.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, pp. 320–324; Doenecke, pp. 96–97; Theriault, pp. 52–53, 56.

- ^ a b Karabell, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Ackerman 2003, pp. 305–308.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 244–248; Karabell, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 320–324; Doenecke, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Theriault, p. 56.

- ^ Doenecke, pp. 99–100; Karabell.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 57–59.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, p. 324; Doenecke, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 59–60.

- ^ TO PASS S. 133, A BILL REGULATING AND IMPROVING THE U. S. CIVIL SERVICE. (J.P. 163). GovTrack.us. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Howe, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Welch, 59–61

- ^ Glass, Andrew (January 16, 2018). "Pendleton Act inaugurates U.S. civil service system, Jan. 16, 1883". Politico.

- ^ a b Kettl, Donald F. (June 21, 2021). "The Battle for the Public Service Is Just Beginning". Government Executive. Washington, DC: Government Executive Media Group LLC.

- ^ White 2017, p. 466.

- ^ White 2017, pp. 467–468.

- ^ United States. Civil Service Reform Act of 1978. Pub. L. 95–454 Approved October 13, 1978.

- ^ Knudsen, Steven; Jakus, Larry; Metz, Maida (1979). "The civil service reform act of 1978". Public Personnel Management. 8 (3): 170–181. doi:10.1177/009102607900800306. S2CID 168751164.

- ^ Rosenbaum, David E. (January 10, 1981). "U.S. Set to Replace a Civil Service Test". The New York Times.

- ^ Berns, Walter (May 1981). "Let Me Call You Quota, Sweetheart". Commentary. New York: Commentary Inc.

- ^ Ban, Carolyn; Ingraham, Patricia W. (1988). "Retaining Quality Federal Employees: Life after PACE". Public Administration Review. 48 (3): 708–718. doi:10.2307/976250. JSTOR 976250.

- ^ Wagner, Erich (October 22, 2020). "'Stunning' Executive Order Would Politicize Civil Service". Government Executive.

- ^ "Executive Order on Protecting the Federal Workforce". January 22, 2021.

Works cited

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2003). Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield. New York, New York: Avalon Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7867-1396-7.

- Barnard, Harry (2005) [1954]. Rutherford Hayes and his America. Newtown, Connecticut: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 978-0-945707-05-9.

- Davison, Kenneth E. (1972). The Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-6275-1.

- Doenecke, Justus D. (1981). The Presidencies of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0208-7.

- Harrison, Brigid C., et al. American Democracy Now. McGraw-Hill Education, 2019.

- Hoogenboom, Ari (1995). Rutherford Hayes: Warrior and President. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0641-2.

- Howe, George F. (1966) [1935]. Chester A. Arthur, A Quarter-Century of Machine Politics. New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co. ASIN B00089DVIG.

- Karabell, Zachary (2004). Chester Alan Arthur. New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-6951-8.

- Paul, Ezra (Winter 1998). "Congressional Relations and Public Relations in the Administration of Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–81)". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 28 (1): 68–87. JSTOR 27551831.

- Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester A. Arthur. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (2002). Rutherford B. Hayes. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6907-5.

- Theriault, Sean M. (February 2003). "Patronage, the Pendleton Act, and the Power of the People". The Journal of Politics. 65 (1): 50–68. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00003. JSTOR 3449855. S2CID 153890814.

- Welch, Richard E. Jr. The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (1988) ISBN 0-7006-0355-7

- White, Richard (2017). The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age: 1865–1896. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190619060.

Further reading

- Foulke, William Dudley (1919). Fighting the Spoilsmen: Reminiscences of The Civil Service Reform Movement. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Hoogenboom, Ari (1961). Outlawing the Spoils: A History of the Civil Service Reform Movement, 1865-1883. University of Illinois. ISBN 0-313-22821-3.

- Shipley, Max L. “The Background and Legal Aspects of the Pendleton Plan.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 24#3 1937, pp. 329–40. online

- Van Riper, Paul P. (1958). History of the United States Civil Service. Row, Peterson and Co. ISBN 0-8371-8755-9.

- Women's Auxiliary to the Civil Service Reform Association (1907). Bibliography of Civil Service Reform and Related Subjects (2nd ed.). New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !