Regency council of Otto of Greece

Kingdom of Greece Βασίλειον τῆς Ἑλλάδος | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1833–1835 | |||||||||

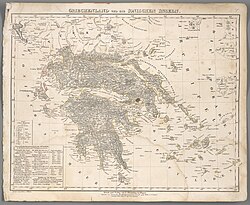

The Kingdom of Greece and the United States of the Ionian Islands after Greek independence | |||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Official languages | Greek and German | ||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodoxy | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Greek | ||||||||

| Government | absolute monarchy (under regency) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Modern | ||||||||

• Arrival of King Otto in Greece | 30 January [O.S. 18 January] 1833 | ||||||||

• Coming-of-age of King Otto | 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1835 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

A regency council (Greek: Αντιβασιλεία, German: Regentschaft) ruled the Kingdom of Greece in 1833–1835, during the minority of King Otto. The council was appointed by Otto's father, King Ludwig I of Bavaria, and comprised three men: Josef Ludwig von Armansperg, Georg Ludwig von Maurer, and Carl Wilhelm von Heideck. The first period of the regency saw major reforms in administration, including the establishment of an autocephalous Church of Greece. The regency's authoritarianism and distrust of the Greek political parties, especially the Russian Party, which was associated with the period of Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias and was particularly opposed to the Church reforms, led to a quick eroding of its popularity. Armansperg was the council's chairman, but increasingly clashed with the other two regents, who in turn aligned with the French Party under Ioannis Kolettis. The main domestic event of the early period was the arrest and sham trial of Theodoros Kolokotronis, a hero of the Greek War of Independence and the de facto leader of the Russian Party, in 1834. This rallied the opposition against the regency, helped provoke a major uprising in the Mani Peninsula, and fatally undermined the prestige of Maurer and Heideck versus Armansperg. The conflict was resolved in Armansperg's favour in July 1834, when Maurer was replaced by Egid von Kobell. Following Otto's coming of age in June 1835, the council was dissolved, but Armansperg remained in charge of the government as Prime Minister.

Background

The London Conference of Britain, France, and Russia in May 1832 established Greece as an independent kingdom under the joint guarantee of the three Powers (article 4), with the 17-year-old Bavarian prince Otto as its hereditary king (articles 1–3).[1] As Otto was a minor, articles 9–10 of the treaty authorized his father, King Ludwig I of Bavaria, to form a three-member regency council that was to rule in his stead until 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1835.[1][2] Further articles concerned the issue of a loan of 60 million francs by the Powers, and the sending of a Bavarian expeditionary force that was to replace the and begin the establishment of a regular Greek army.[1]

First regency council

Establishment

Based on the provisions of the Treaty of London, King Ludwig established the three-member regency as a collegial body on 23 July [O.S. 11 July] 1832: although one of the three regents was to chair the body, all decisions were to be taken by vote, and were to be valid only when signed by all members.[3] On 5 October [O.S. 23 September] 1832, the three regents were named: Count Josef Ludwig von Armansperg as chairman of the council, the law professor Georg Ludwig von Maurer as member responsible for justice, education, and religious affairs, and the general Carl Wilhelm von Heideck as member responsible for military and naval affairs. In addition, the diplomat Karl von Abel was named secretary and substitute member with responsibility for internal administrative and foreign affairs, and the official Johann Baptist Greiner was to serve as liaison between the regency and the ministries, with a special role overseeing financial affairs.[3]

The regents were chosen out of a mixture of practical and political reasons. Count Armansperg was an experienced statesman, but had been dismissed by Ludwig as finance minister in 1830 due to his support for the July Revolution in France. He was thus considered to have liberal sympathies, which gained him the backing of Britain and France. King Ludwig distrusted him, and tried to curtail his powers, but Armansperg rebuffed these attempts, insisting on the need for the Greek regency to remain independent of any foreign influence.[4] Of the three regents, General Heideck was the only one with experience of Greece, as he was a philhellene who had joined the Greek War of Independence in 1826, fighting alongside the Greek rebels. He sympathized with, and was backed by, Russia. Maurer and Abel were relatively apolitical: Maurer was an erudite scholar and former justice minister of Bavaria, and Abel was a capable, experienced and hard-working bureaucrat.[4]

The 'Bavarocracy'

Otto and his entourage arrived at Nafplion, then the capital of Greece, on 30 January [O.S. 18 January] 1833.[5] In theory, the new monarchy would be constitutional. Indeed, this had been explicitly promised both by the Powers and by the Bavarian foreign minister, Friedrich August von Gise. However, King Ludwig was firmly opposed to this, believing that a too-democratic constitution would impede his son's ability to rule effectively. In view of the chaotic circumstances in Greece, this view was shared by the regency members. No constitution was promulgated either before or after Otto's arrival in Greece, leaving the regency the only effective decision-making body in the country. The only limit on its authority was the prerogative of King Ludwig to dismiss its members and appoint new ones.[6]

Furthermore, in their efforts to quickly transform Greece into a European-style state, the regency did not examine the local conditions objectively, but tried to directly import European norms and regulations, which were completely inappropriate for the war-ravaged and destitute country, and failed to take into account the sensibilities of the local population. The regency was particularly suspicious of the irregular soldiers who had fought the War of Independence, and failed to either recompense them with the public lands captured from the Turks, as promised, nor to provide them with employ by taking them into the army. This led to them turning to brigandage, both in Greece and across the border into the Ottoman territories.[7]

As a result, in its efforts to reduce the country to obedience and establish order, as well as to minimize the influence of the Greek factions and Westernize the country as fast as possible, it could only rely on foreign, chiefly Bavarian officials, and on the bayonets of the Bavarian expeditionary corps.[8][9] Thus the regime instituted quickly became known as the 'Bavarocracy' (Βαυαροκρατία), which was chiefly pronounced in the court and the army, where the Bavarians greatly outnumbered the Greeks. In the army, all senior positions were given to Bavarians or other foreigners: Wilhelm von Le Suire became Minister for Military Affairs; Christian Schmaltz Inspector-General of the Army; Anton Zäch head of the engineers; Ludwig von Lüder head of the artillery; the French philhellene François Graillard head of the Gendarmerie; and the British philhellene Thomas Gordon chief of the general staff.[10] It is notable that similar measures to concentrate command authority in the hands of foreigners were not undertaken in the navy, which on its own could not challenge the regime.[10] This 'Bavarocracy' was not so evident in the civil administration, where only a few foreign officials were appointed, but by royal decree on 15 March 1833, the existing Greek cabinet of seven ministries was subordinated to the regency, thus becoming merely an executive organ carrying out the regency's dictates.[11]

The new regime and its reforms

The regency's tendency to sideline and patronize the Greeks, governing in their name but not with their active participation, has been considered by historians as a cardinal mistake, and became the chief source of opposition to the regency.[12] This was coupled with an attempt to neutralize the Greek parties—the English, French and Russian—that had developed since the War of Independence, around affiliation to one of the guarantor Great Powers.[13] To the regency, these parties were little more than elite cliques, rather than broader political movements expressing the Greek people. The regency tried to curtail their activity, especially through a system of "divide and rule" in making appointments to public office, and adopted an inflexibly confrontational stance whenever its decisions were challenged by the parties.[13] At the same time, the parties' tendency to appeal to their respective patron Powers were regarded as inimical to the regency's attempts to assert the country's independence from Great Power interference, providing another reason for the regency's attempts to neutralize them.[14] For the same reason, at least initially, the regency has closer ties with France than the other two guarantor Powers, since Britain and Russia were seen as actively vying for influence over the newly independent kingdom, whereas France was less interested in direct involvement and thus considered relatively neutral. Maurer in particular was French-leaning, leading to a close relationship with the French ambassador, Baron Rouen.[14]

On its arrival in Greece, the regency initially retained the previous cabinet under Spyridon Trikoupis until 15 April 1833, when the cabinet was reformed. Trikoupis remained its president, with Alexandros Mavrokordatos, Georgios Psyllas, Georgios Praidis, and Ioannis Kolettis as ministers.[15] The new cabinet was dominated by the English Party, with only Kolettis, in the relatively unimportant Ministry for Naval Affairs, from the French Party, while the Russian Party was not represented at all.[15] Indeed, most of the men who had held office under Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias (1828–1831) were kept out of office.[15] In the army, the distinguished commander-in-chief of the War of Independence, Theodoros Kolokotronis, was kept out of military command due to his pro-Russian sympathies, which in turn led to the dismissal of several other prominent commanders from the other political camps to assuage the Russians.[15] The Russian Party thus switched to a position of complete opposition to the regency, expressed chiefly via its mouthpiece, the newspaper Chronos, funded by Kolokotronis.[15]

Finances

The financial situation of Greece when Otto arrived was disastrous: the treasury was empty, the country owed large amounts to foreign lenders due to the loans contracted to finance the War of Independence, and much of the public lands had been illegally seized. Indeed, the scale of the problem was hard to assess as the financial administration was practically non-existent; the relevant census and cadastral data were either lacking or had been destroyed in the anarchy of 1831–32.[16] The regency could look forward to the first part of the promised sixty-million-frank loan, which was finalized in July 1833, but even that was much reduced in practice due to commissions and the need to pay off previous debts.[16] The regency thus set about a programme of reduction of expenses, restoring security and tranquility so that agriculture and commerce could resume, and ending tax evasion and the mismanagement of public funds.[16] The latter point in particular meant a confrontation with the Greek political factions and local magnates, who had benefited from the previous situation and now vigorously opposed the regency's efforts, even to the point of sponsoring uprisings or seeking the intervention of the Powers in their favour.[16]

As the first step, in October 1833 the Court of Audit was founded as an independent institution to audit public finances. It comprised seven members, headed by a Frenchman, Arthémond Jean-François de Regny. Its extensive authority over all matters of financial policy made it the second-most powerful body after the regency itself.[16] In addition, public treasuries were established in the national and the main provincial capitals.[16] Due to the pressing financial needs, the regency continued the previous system of tax farming, but tried to limit abuses by requiring the presence of the—theoretically impartial—eparchs and ephors at the bidding process, by reducing the extent of the concessions to the level of individual communes rather than entire provinces, and by permitting the payment of the contracted sum in rates. This effectively broadened the circle of people who were able to bid for the contracts, rather than the small clique of wealthy or politically influential people who had dominated the process before.[17] Attempts were made to begin the direct gathering of taxes by state officials, but this was only sporadically implemented, in areas where the tax proceeds were very low.[18]

Army

When Otto arrived in Greece, the military forces established by Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias still existed on paper, numbering 5,000 irregulars and 700 men of the regular army, all of them veteran fighters of the War of Independence. In practice, since they received no pay from the central government, they lived off the land.[19] The fate of these men was one of the most intractable problems for the new regime: as most of them were professional soldiers, they were vehemently opposed to taking up any other profession, especially in agriculture, which they regarded as dishonorable. Instead, they looked to the government to provide them with a suitable position, rent, or some estate; furthermore, for many of them, who came from the parts of the Greek world outside the borders of the new Greek kingdom, a return to their homes was practically impossible.[20] A further complication was the dubious loyalty of these men, who followed their old chieftains, who in turn were followers of various political figures. To King Ludwig, who wanted to establish a firm central government, these soldiers were a liability.[19]

As a result, already in the autumn of 1832, the regency decided to dismiss the irregular troops and build an entirely new army around a core provided by the Bavarian expeditionary force. The latter was to be composed of 3,500 volunteers, but until they could be recruited, King Ludwig provided men from the Bavarian Army instead.[21] The existing regular troops were abolished by royal decree on 25 February, followed by the irregulars on 2 March. These were replaced by ten battalions of light infantry (termed Ἀκροβολισταί, "Skirmishers" in Greek) with an envisaged size of about 2,000 men in total. These were specially designed to attract men from the disbanded irregular troops, who despised Western-style uniforms and preferred their own traditional dress.[22] In practice, the results of these measures were negative: the veterans of the War of Independence felt aggrieved, and matters became worse when the regency used military force to disband their camp at Argos, where they had assembled to protest. Left without employ, many turned to brigandage instead, while popular opinion overwhelmingly turned against the regency.[22]

The backlash forced the regency to backpedal somewhat: on the occasion of Otto's birthday on 20 May, it issued an amnesty for those of the fighters of the War of Independence who had fled to Ottoman territory, but with the proviso of enlisting in the new regular army instead.[23] On the same date, the Royal Gendarmerie was established, offering prospects of employment to 1,200 veteran fighters. However, due to the western dress required and the fighters' distrust to the regency, recruitment proved slow: about a third of the positions remained unfilled a year later.[24]

The problem of the veteran fighters remained largely unresolved. The regency preferred to rely on the regular forces under its control, and only made some mostly symbolic and thus ineffectual gestures towards satisfying the veterans' demands. Thus on 20 May 1834, a medal was issued to the veterans of the War of Independence, which was tied to certain privileges. At the same time, the prospect of awarding public land to the veterans was announced, but tied to severe conditions.[24]

Administration

On 3 April 1833, a royal decree reformed the country's administrative system: municipalities (δῆμοι, demoi) became the first-level administrative units, grouped into 47 provinces (ἐπαρχίαι, eparchiai) and then into ten prefectures (νομαρχίαι, nomarchiai).[24] At the head of the provinces and prefectures was an appointed official (eparch/nomarch), while municipalities were led by an elected demarch. An elected council was envisaged to assist these officials at each level. While paying lip service to the traditions of local self-government that had emerged in the Greek world during Ottoman rule, in practice the system was highly centralized, since the councils' authority was deliberately limited, and the limited suffrage used in the election of the demarchs led to their de facto selection by the government.[24] The regency was motivated in this by the subversion of local authorities by the local magnates; much like their predecessor, Governor Kapodistrias, the regents saw in a strongly centralized system the only answer capable of eliminating the magnates' political power.[16]

For the same reason, care was taken to limit the powers of the local officials, by splitting up authority into precisely circumscribed areas among several officials, all reporting to the centre. Thus the nomarch effectively shared power with the local metropolitan bishop, the ephor of the financial services, the public treasurer, and the prefecture-level heads of the Gendarmerie, medical service, and engineers corps. Military and naval affairs were excluded from civilian control, as were the courts, which in turn were prohibited from interfering in any way with the nomarch's duties.[24] Approval from the central government had to be sought even for some decisions on minor local matters, while a careful antagonism was set up between the prefectural/provincial and the municipal authorities: the former could veto the latter's initiatives, but the latter could in turn appeal to the Ministry of the Interior. This system resulted in a hyper-centralized administration, where the regency could control even the minutiae of local government.[25]

Church affairs

As with other areas of Greek public life, the Orthodox Church had suffered during the War of Independence and its aftermath. During the war, the Church was effectively cut off from its leadership, in the form of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, leaving a large part of the dioceses unoccupied. This, along with the almost complete collapse of the monasteries, which were almost emptied during the first years of the war, and the influx of clergy fleeing from Ottoman reprisals, destroyed the cohesion of the hierarchy; as a result, the fragmented priesthood became increasingly involved with the various political factions vying for power.[18] Along with having to restore order in ecclesiastical affairs, the regency also faced the challenge of securing the independence the Greek Church from external influences, chiefly that of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.[18]

Maurer was tasked with the issue as part of his portfolio. A Protestant, and in line with the regency's centralizing policies, he favoured bringing the Church under firm state control.[18] For this, Maurer relied chiefly on the advice of Theoklitos Farmakidis, an Orthodox cleric who was also a prominent figure of the Modern Greek Enlightenment.[18] Farmakidis was a member of the seven-man commission appointed by Maurer to examine ecclesiastical matters. This was chaired by Spyridon Trikoupis (who along with being President of the Ministerial Council and Foreign Minister was also the Minister for Ecclesiastical and Education Affairs), with Farmakidis, Panoutsos Notaras, Skarlatos Vyzantios, Konstantinos Schinas, Bishop Ignatios of Ardamerion, and Bishop Paisios of Elaia and Messenia, as members.[26] The composition of the commission predetermined its recommendations: the lay members were in the majority, and Farmakidis, Trikoupis, Schinas and Vyzantios were known to have liberal views, and represented a small but influential intelligentsia that saw in the War of Independence a struggle for freedom not only from Ottoman tyranny, but also from the Patriarchate.[27] For the liberals, the new Greek kingdom was the only legitimate national authority, and the Church simply another branch of administration. The liberal intelligentsia, educated in Western Europe, also distrusted the Church hierarchy, whom it regarded as uneducated, venal and reactionary; while the Patriarch, who was subject to both Ottoman and Russian influence, was to be prevented from interfering in the internal affairs of the Greek kingdom.[15]

The conservative faction, on the other hand, still considered the Patriarchate as the national institution par excellence, and distrusted both the regency and the non-Orthodox King, as well as the Western-aligned intelligentsia.[15] Rumours quickly spread about the regency's intentions to declare the Greek Church autocephalous, and even that its ultimate motive was to turn the Greeks into Catholics or Protestants. The monk Prokopios Dendrinos led popular protest, while the former Metropolitan of Adrianople sought to rally the Church hierarchy in opposition, with the assistance of the Russian ambassador, Gavriil Antonovich Katakazi,[26] himself a Phanariote Greek from Constantinople.

The result of the commission's deliberations was the royal decree of 23 July 1833. It established the Church of Greece as an autocephalous body. While retaining spiritual communion with the Patriarchate, the Church would come under the control of the Greek state: the King was the head of the Church, which was to be administered by a Holy Synod, whose five members had to be approved by the King. While the Synod had authority over the Church's internal affairs, ultimate royal control was ensured by the attendance of a royal commissioner—a post occupied by Farmakidis—at its meetings, while all synodal decisions had to be ratified by the King. Furthermore, the Minister for Education and Ecclesiastical Affairs had the right to examine and revise its decisions.[18] Further edicts followed, regulating the monasteries: on 7 October 1833, all monasteries with fewer than six monks were dissolved; on 9 March 1834, all female convents but three were dissolved, and all nuns under the age of 40 were ordered to abandon the monasteries and return to lay life; and on 8 May 1834, all private donations to the Church were banned, and all monastic properties became state property, with the aim of using it to finance the state education programme and provide some financial assistance to the lower clergy.[15] The decisions were partly politically motivated: the monks as a whole were pro-Russian, and frequently acted as agents of dissent and rebellion against the new regime.[28] Out of 524 existing monasteries, only 146 survived after these decrees; 63 because they were located in the Mani Peninsula, where the regency granted special privileges after the Maniot rebellion of 1834.[15]

The regency's decisions were widely regarded as high-handed and foreign to Greek customs, and encountered widespread opposition among both the people and the clergy, backed by Russia.[15] The Orthodox hierarchy rejected the decrees and continued to insist on the primacy of canon law for its internal governance,[15] while in the heated political atmosphere of the period, the ecclesiastical issue quickly became another rallying point in the rebellions against the regency and Otto's later absolutist rule.[15]

Arrest of Kolokotronis and the ascendancy of the French Party

Already on 3 February 1833, Kolokotronis, while a guest on board the flagship of the Russian admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Ricord, wrote to the Russian foreign minister, Karl Nesselrode, to protest about the regency's Church reforms. Nesselrode's reply, delivered by Katakazi, encouraged the Greeks to rally around the throne, but stand firm in matters of faith.[29] The letter was widely disseminated among those disaffected by the regency, who saw it as a signal of Russian support.[30] At the same time, supporters of the Russian Party circulated a petition to the Tsar, calling for the dismissal of the regency and the immediate assumption of power by Otto.[30] In parallel, another petition was being circulated by Professor Frantz, an interpreter working for the regency council. Its aim was to dismiss Maurer and Heideck, leaving Armansperg as the sole regent. The latter's involvement in this affair is unprovable, but likely, given his expressed opinion on the unworkability of the collective leadership, and his later actions. In the same spirit, Armansperg also discretely let it be known the Russian Party's adherents that the regency's hostility to them was due mostly to Maurer and Heideck.[30]

These two supposed "conspiracies"—of the Russian Party and of Professor Frantz—resulted in the first political crisis of the regency. Fearful of both Russian-sponsored uprising and the concentration of power in Armansperg's hands, the other two regents pushed through the deportation of Frantz in late August, and on 6 September, had Kolokotronis and other leading officers linked to him and the Russian faction—including his son Gennaios and the generals Dimitris Plapoutas and Kitsos Tzavellas—arrested and imprisoned in the Acronauplia citadel.[30] The whole affair had been kept secret to the last minute, and not even the cabinet was informed; this led to the resignation of Trikoupis, Interior Minister Psyllas, and Justice Minister Praidis, and the cabinet was reformed in October under Mavrokordatos.[31] Trikoupis was effectively neutralized by being sent as ambassador to Britain, while restrictions were put in place on 6 and 11 September on journalists and the press, curtailing their ability to criticize the government. These restrictions soon led to the closing of two major opposition newspapers, Ilios and Triptolemos.[32]

The big winner of the crisis was Kolettis, who moved to the Interior Ministry and quickly began dismissing adherents of the English and Russian parties from office, appointing men loyal to him instead.[32] Kolettis and the new Justice Minister, Schinas, who was hated by the Russian Party due to his involvement in the Church reforms, were considered a safe pair of hands to push forward the prosecution and trial of Kolokotronis and his associates due to their deep political differences.[32] The regency's alignment with Kolettis' French Party became even more blatant: the party was now officially referred to as the "national" party, and its mouthpiece, the newspaper Sotir, was declared as a semi-official organ of the government, being printed in the Royal Printing Office and subsidized by the government budget.[32] As the historian John A. Petropulos comments, this affair also marked the failure of the regency's initial policy of remaining aloof from Greek political squabbles: in its attempt to counter the ambitions of the Russian Party, the regency unwittingly had reduced itself to being little more than the sponsor of the French Party.[32]

Rallying of the opposition and the trial of Kolokotronis

The regency's policies alienated the two thirds of the Greek people represented by the English and Russian parties, and particularly antagonized Russia, which was already at odds with the regency over the Church reforms.[33] The seeming triumph of the French Party only served to draw its opponents together. Armansperg allied with the British ambassador, Edward Dawkins, in their joint efforts to discredit Maurer and Heideck. The latter sent repeated protests to British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, demanding Dawkins' recall, but this only red to a stern rebuff from Palmerston in April 1834, and the further shift of official British policy against them and in favour of Armansperg.[32]

At the same time, Dawkins approached Katakazi, and the English and Russian parties entered into closer contact, rallying around the common purpose of securing a favourable outcome for the upcoming trial of Kolokotronis and his co-defendants.[32] The impending trial was thus turned into a political tug-of-war: for Maurer and Heideck, the condemnation of Kolokotronis was now a political necessity, as anything else would be a heavy blow to the regency's prestige.[34]

The preparations for the trial were made accordingly: the Scottish philhellene Edward Masson was appointed as lead prosecutor in the affair, with the Greek Kanellos Deligiannis as his aide. Not only were both men followers of the French Party, but Deligiannis had a long-standing rivalry with Plapoutas over property disputes.[34] Their task proved very difficult, since few people were found willing to come forward against the defendants, whether out of party loyalties or deference to Kolokotronis' status; conversely, those that did, were either known to be rivals to the defendants, or men of low social standing.[35] Two of the judges were also dismissed, suspected of Russian sympathies.[36]

On 7 March 1834, Kolokotronis and Plapoutas were formally charged with having organized a conspiracy aiming at overthrowing the legal order, citing the letter to Nesselrode and the petition to the Tsar as evidence. The indictment accused both men of high treason, and recommended the death penalty for them.[36] While the contacts of the two defendants with foreign powers were undoubtedly true, the indictment was generally considered as baseless: not only did the prosecution fail to bring any credible evidence for a planned uprising against two men who were widely considered as heroes of the War of Independence, but such intrigues with the guarantor Powers had been the staple of Greek politics. The infighting among the regency, which by then had become common knowledge, further served to discredit the whole affair by exposing the trial as politically motivated.[36] The English Party publicly condemned the whole process, leading to the dismissal of Mavrokordatos—he too was safely sent away by being appointed ambassador to Russia and Bavaria[32]—as head of the government, and his replacement by Kolettis.[36]

The trial went on regardless, and indeed ended in a condemnation and sentencing to death by three of the five judges. The two dissenting judges, Anastasios Polyzoidis and Georgios Tertsetis, refused to sign the decision, and had to be coerced to do so by the courthouse guards. In retaliation, they were dismissed from office by the regency and prosecuted.[36] Although Maurer and Heideck had managed to secure the outcome they sought, the decision was widely considered unjust and the result of coercion. King Otto soon intervened to commute the sentences to imprisonment, first for life and then for twenty years. Bitterly opposed by Kolettis, this royal intervention was popularly credited to Armansperg, further diminishing the prestige of his two co-regents.[36]

Mani Uprising

The trial of Kolokotronis directly led to the outbreak of an uprising in the Mani Peninsula in the southern Peloponnese.[36] The regency had decided to dismantle the around 800 fortified tower houses in the region.[36] The Maniots, a warlike people who had withstood the Ottomans and Egyptians during the War of Independence, were incensed at this decision. This was a typical example of Bavarian insensitivity to local peculiarities: where the regency saw in these buildings only a dangerous military asset that might be used to challenge its authority, to the Maniots these were their homes, whose destruction without recompense would leave them destitute.[37] For a few months, the regency's local agent, the Bavarian officer Maximilian Feder, had managed to remain in control of the situation, through a judicious mixture of bribery and force, but this ended with the start of the trial, when the region erupted into revolt. It is likely that at least some of Kolokotronis' supporters exhorted the Maniots to rise up, but another factor were the rumours, spread by Orthodox priests and local landowners alike, which claimed that the demolition of the tower houses was but the first step in eroding the region's traditional autonomy and imposing a poll tax, that the Maniots had successfully resisted paying even to the Ottomans.[36]

About 2,500 men of the Bavarian expeditionary corps under General Schmaltz were sent to suppress the uprising, but to no avail.[36] The Bavarians' unfamiliarity with the climate and terrain, to which the Maniots and their tactics were perfectly adjusted, meant that they could achieve little: in the harsh mountains, the Bavarians were unable to deploy larger formations or even provide effective artillery support, while the Maniots resorted to their time-honoured guerrilla tactics against their lumbering, heat-exhausted opponents.[38] The Bavarians were also completely unprepared for the cruelty of the Maniots: captured soldiers were sometimes put in bags with wild cats, or gradually mutilated. At best, they were stripped of weapons and clothes and sent back naked to their lines.[38]

Unable to make headway, the regency was forced to climb down. The two most important Maniot families, Tzanetakis and Mavromichalis, acted as mediators in the negotiations, which resulted favourable terms for the Maniots: the Maniots were promised respect for their autonomy, including the right to enlist in separate military units, the payment of subsidies, the revocation of the monastic legislation for the region, and non-interference in their affairs.[36][38] The upshot of the affair was that the government ended up pouring into Mani twice the sums that it received from it in taxes,[38] and that the myth of the Bavarians' invincibility was broken, severely tarnishing the regency's prestige and authority and encouraging future revolts.[39]

Second regency council

Recall of Maurer and Abel

The internal crisis of the regency continued to mount throughout the spring and early summer of 1834.[40] King Otto distrusted Armansperg and sided with the majority of the regents against him,[41] but the decisive arena in which the rivalry was fought out was the Bavarian court, where gradually the ambassadors of the three guarantor Powers joined in—at least tacit—support of Armansperg. Despite the pro-French stance of Maurer and Heideck, the French government decided to follow Britain on the issue, all the more so since Armansperg was also judged to be favourably disposed to France.[40] As a result, in July, King Ludwig recalled Maurer and Abel to Bavaria, replacing the former with Egid von Kobell. This marked the end of the so-called "First Regency" (Πρώτη Αντιβασιλεία) with a complete triumph for Armansperg. This was widely seen—particularly by France and Russia—as a victory for the British. Nevertheless, Russia at least was prepared to wait out developments, and held out its acquiescence to the political changes enacted until then as a quid pro quo for a more favourable stance by the new regency.[40] In Greece, the news of the change, which arrived only in August, were received with relative equanimity. Armansperg's success was counterbalanced by the precariousness of his position—the regency's term was to end in less than a year—and the influence of Kolettis.[42]

Rebellion in Messenia

In the meantime, continued unrest among the supporters of the Russian and English parties had led to preparations for another uprising against the government. The movement was led chiefly by disgruntled Russian Party adherents, but had attracted the support of several English Party figures, especially following the ouster of Mavrokordatos from the government, and plans were under way to raise in revolt the islands of Hydra and Spetses, as well as Roumeli (Continental Greece), in order to overthrow the regency.[43] Given the involvement of English Party figures, Armansperg himself may have been involved in the plans, or at least tolerated them, in order to use any uprising as political ammunition against his rivals,[44] while others, like Ioannis Makriyannis, thought that Kolettis was involved in the uprising, for the same reasons.[45] The government's mishandling of the Mani uprising encouraged the conspirators about their chances of success.[45]

However, the downfall of Maurer and Abel for the moment eased tensions, and the uprising, when it broke out in Messenia on 11 August 1834, was limited to its original core, men like the nephews of Plapoutas, the elderly chieftain Mitropetrovas, Yannakis Gritzalis, and Kolokotronis' nephew, Nikitas Zerbinis.[43] The rebels issued a manifesto in which they bemoaned the tyranny imposed by the lack of a constitution, the harsh taxation, and the religious policies that attacked Orthodoxy, and demanded the abolition of the regency and the assumption of government by King Otto, the release of Kolokotronis and Plapoutas.[45]

The outbreak of the revolt caught Kolettis' government by surprise, but it reacted quickly and decisively: martial law was declared on 16 August, Andreas Zaimis was sent to Messenia as head of an investigative commission, amnesty was granted to the Maniot chieftains, the Roumeliote chieftains were mollified with promotions, and Minister of Education Schinas, who as one of the chief authors of the regency's ecclesiastical reforms had attracted particular condemnation in the rebels' manifesto, was dismissed.[46] These measures ensured that the uprising did not spread as widely as initially feared, while forces loyal to the government quickly regained the initiative. General Schmaltz formed a corps of 1,00 regular army troops and 500 Maniots and march against the rebels, defeating them at Aslan Agha (modern Aris). At the same time, several unemployed military commanders, led by the Roumeliot chieftain Theodoros Grivas and Hatzi Christos Voulgaris, eager to ingratiate themselves with the government and secure commissions, raised local irregular militias and attacked the rebels from the north.[45]

Within a week, the rebellion was suppressed. Gritzalis, Anastasios Tsamalis, and Mitropetrovas were condemned to death by courts-martial; Mitropetrovas was pardoned due to his distinguished service in the War of Independence and advanced age, but the other two were immediately shot.[45] Another wave of anti-Russian Party purges followed, with many of their leaders, and the relatives of Plapoutas and Kolokotronis, landing in prison. Plapoutas and Kolokotronis themselves narrowly escaped execution in the heated atmosphere of the times.[45] The affair redounded to the immense benefit of Kolettis: the Russian Party was almost wiped out, Armansperg was forced to—however temporarily—align himself with him, and the rehabilitation of Roumeliot chieftains through their use in the rebellion's suppression enhanced Kolettis' own influence among them.[47] For this reason, Armansperg actively sought to prevent a complete triumph by his rival. The appointments of Andreas Zaimis, a declared enemy of Kolettis, and of the moderate philhellene Thomas Gordon as chairman of the court-martial, were aimed at limiting the reprisals to the main instigators, and succeeded in dismissing the notion of a wide-ranging Russian Party-led conspiracy. This in turn allowed Armansperg to secure the release of many of the Russian Party's leaders, placing them in his debt.[48]

Rivalries between Armansperg, Kolettis, and Otto

With the rebellion suppressed, the rivalry between Kolettis and Armansperg became more pronounced. As the end of the regency's term drew near, it became evident that Otto, due to his youth and inexperience, would need to appoint a prime minister to handle government matters on his behalf.[48] Armansperg was an obvious candidate for the position, but his relationship with Otto was marked by deep mistrust from the King. The main reason was the affair of the King's health. Over the course of 1834–35, the royal physician, Witber, sent four reports to King Ludwig detailing Otto's physical and mental inability to carry out his duties.[49] Armansperg had not been directly involved in them, but the courtiers responsible for composing them belonged to his faction, and the new British ambassador, Sir Edmund Lyons, soon started spreading rumours about Otto's frailty to the Greek public—in later years, the British would make public use of these documents in the press to discredit Otto.[50]

Since Otto's distrust towards Armansperg was an open secret, this led to jockeying for position among the members of the regency and the court. The Greeks were largely left out of this contest, apart from Kolettis, who aimed to diminish Armansperg's standing and promoted himself as the only viable Greek candidate for the position of Prime Minister after the end of the regency.[48] As part of this political infighting, Armansperg deprived Kolettis' mouthpiece, the newspaper Sotir, of its semi-official status and government founding, and established a newspaper of his own, Ethniki. In turn, Sotir now attacked Armansperg for the leniency he had shown to the rebels. [48] Nevertheless, Armansperg and Kobell were reluctant to simply dismiss Kolettis, as they needed his knowledge of Greek political affairs. At the same time, Kolettis' own supporters successfully promoted the idea that only he could guarantee stability and peace against rebellions and brigands, while threatening chaos if he should be forced to resign.[48] Kolettis himself for a while encouraged the ambitions of the Bavarian Minister for Military Affairs, Le Suire, to supplant Armansperg, since Le Suire would be a much less formidable rival.[48] The British ambassador, Dawkins, also appeared willing to side with Kolettis once Armansperg tried to reconcile with Katakazi and the Russian Party, but this fell through due to the close identification of British interests in Greece with Armansperg.[48]

King Otto was encouraged in his opposition to Armansperg by the other remaining member of the First Regency, Heideck, and through him remained in contact with Abel and Maurer. Otto initially attempted to have Abel return to Greece, but made the mistake of informing Ambassador Lyons of this plan. Abel's return was opposed not only by Lyons, but also very unpopular among the Greeks due to his role in disbanding the irregular Greek units and in the Church reforms, so this plan failed.[49] Furthermore, King Ludwig held fast onto Armansperg, chiefly since he was the only Bavarian of suitable ability who was acceptable to the European courts, having the open backing of the British and Austrians, and at least the tacit acceptance of the French and even the Russians. Armansperg thus represented the only compromise candidate able to satisfy the Powers.[51] Ludwig furthermore endeavoured to lessen Russia's opposition to Armansperg by championing a rapprochement with the Russian Party, with measures such as the pardon and amnesty for Kolokotronis.[51]

Transfer of the capital to Athens

The issue of a new capital for the Greek kingdom had been debated for some time, with the existing capital of Nafplion, as well as Corinth, Megara, Argos, and Piraeus considered as candidates. In the end, Athens won out due to its incomparable prestige as a major centre of Classical Antiquity; King Ludwig, who was enamored of Classical civilization, was a fervent proponent of the idea.[51] A royal decree on 18 September 1835 declared Athens as the new capital,[51] but the court with the king did not move in until 1837.

The new capital had been devastated during the War of Independence, however, so that the government had to undertake a major construction effort to provide even rudimentary accommodation and facilities, such as a hospital, for the court, government, and officialdom.[51] Indeed, Kolettis was able to use his advance knowledge of Athens' selection and government position to allow many of his followers to snatch up lucrative pieces of land there, especially in the harbour of Piraeus, in expectation of the rapid urban and economic development that would follow.[48]

Similar efforts were undertaken in other Greek towns, such as Patras, Piraeus, and Ermoupoli in Syros.[51]

Assessment

References

- ^ a b c Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 31.

- ^ Note: Greece officially adopted the Gregorian calendar on 16 February 1923 (which became 1 March). All dates prior to that, unless specifically denoted, are Old Style.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 34.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 33.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Seidl 1981, pp. 113–120.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Seidl 1981, p. 138.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 36.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 51.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 45, 51.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f g Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 41.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c d e f Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 42.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 38.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 39.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c d e Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 40.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 43.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c d Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 46.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 47.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 48.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 49.

- ^ Seidl 1981, pp. 130–134.

- ^ a b c d Seidl 1981, p. 134.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 50.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 50, 53.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e f Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 55.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 56.

- ^ a b Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 57.

- ^ Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d e f Petropoulos & Koumarianou 1977, p. 58.

Sources

- Mavromoustakou, Ivi (2003). "Το ελληνικό κράτος 1833 - 1871, Β. Πολιτικοί θεσμοί και Διοικητική οργάνωση" [The Greek State 1833 - 1871. II. Political Institutions and Administrative Organisation]. In Panagiotopoulos, Vasilis (ed.). Ιστορία του Νέου Ελληνισμού 1770 - 2000, 4ος Τόμος: Το ελληνικό κράτος, 1833-1871. Η εθνική εστία και ο ελληνισμός της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας [History of Modern Hellenism 1770 - 2000, 4th Volume: The Greek State, 1833-1871. The National Centre and Hellenism in the Ottoman Empire]. Athens: Ellinika Grammata. pp. 27–50. ISBN 960-406-540-8.

- Petropoulos, Ioannis & Koumarianou, Aikaterini (1977). "Περίοδος Βασιλείας του Όθωνος 1833-1862. Εισαγωγή & Περίοδος Απόλυτης Μοναρχίας" [Reign of Otto 1833-1862. Introduction & Absolute Monarchy Period]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΓ΄: Νεώτερος Ελληνισμός από το 1833 έως το 1881 [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XIII: Modern Hellenism from 1833 to 1881] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 8–105. ISBN 978-960-213-109-1.

- Petropulos, John A. (1968). Politics and Statecraft in the Kingdom of Greece, 1833–1843. Princeton University Press.

- Seidl, Wolf (1981). Bayern in Griechenland. Die Geburt des griechischen Nationalstaats und die Regierung König Ottos [Bavaria in Greece. The Birth of the Greek Nation-State and the Reign of King Otto] (in German) (New and expanded ed.). Munich: Prestel. ISBN 3-7913-0556-5.

- Tsapogas, Michalis (2003). "Η ανανέωση του δικαίου. Επίσημο δίκαιο και τοπικά έθιμα, 1833-1871" [The Renewal of Law. Public Law and Local Customs, 1833-1871]. In Panagiotopoulos, Vasilis (ed.). Ιστορία του Νέου Ελληνισμού 1770 - 2000, 4ος Τόμος: Το ελληνικό κράτος, 1833-1871. Η εθνική εστία και ο ελληνισμός της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας [History of Modern Hellenism 1770 - 2000, 4th Volume: The Greek State, 1833-1871. The National Centre and Hellenism in the Ottoman Empire]. Athens: Ellinika Grammata. pp. 51–58. ISBN 960-406-540-8.

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !