1912 Republican Party presidential primaries

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1,074 delegates to the Republican National Convention[1][2] 538 votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taft Roosevelt/Not Voting[a] La Follette Cummins | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

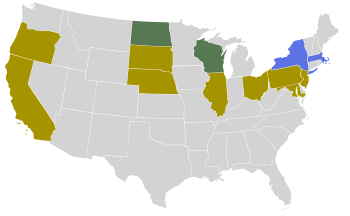

From January 23 to June 4, 1912, delegates to the 1912 Republican National Convention were selected through a series of primaries, caucuses, and conventions to determine the party's nominee for president in the 1912 election. Incumbent president William Howard Taft was chosen over former president Theodore Roosevelt.[4] Taft's victory at the national convention precipitated a fissure in the Republican Party, with Roosevelt standing for the presidency as the candidate of an independent Progressive Party, and the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson over the divided Republicans.

For the first time, a large number of delegates were selected through direct primary elections rather than local or state party conventions. Primary elections were a progressive reform supported by Roosevelt and his allies, and the primaries were largely dominated by Roosevelt or Robert M. La Follette, a fellow progressive who entered the race early. However, President Taft was equally dominant under the traditional caucus and convention systems, where executive patronage power could be leveraged in his favor and party bosses were able to maneuver delegations towards him.

At the conclusion of the delegation selection process, Roosevelt had won 411 instructed delegates, Taft had 201, and 254 were contested between the two candidates. Of the remaining delegates, 46 were pledged to the minor candidates Albert B. Cummins and Robert M. La Follette and 166 were uninstructed.[5] In the end, Taft won the vast majority of the party conventions, delivering him a working majority outright, and many Roosevelt supporters abstained from voting at the convention before forming their own party.

Background

1908 presidential election

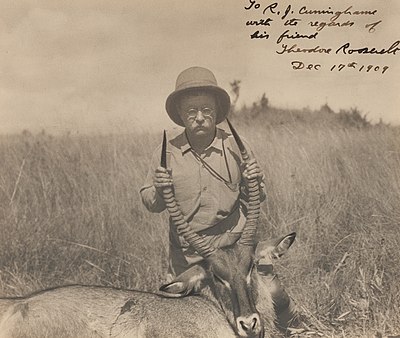

In 1908, popular incumbent president Theodore Roosevelt declined entreaties to seek another term in office, keeping to a spontaneous pledge he made upon securing re-election in 1904.[c] His initial choice for a successor was Secretary of State Elihu Root, but Root's career as a corporate attorney had rendered him unpalatable to progressives, and he declined to seek the presidency.[6] Instead, Roosevelt endorsed Secretary of War William Howard Taft. With Roosevelt's support and steadfast refusal to accept the nomination himself, Taft easily won the Republican nomination and the general election over William Jennings Bryan. Roosevelt, after privately expressing some skepticism over Taft's decision not to retain his cabinet officers, departed for and European tour which kept him overseas into 1910, at least in part to give Taft latitude to operate politically.

Roosevelt's return trip from Khartoum brought him international as well as domestic prestige. He was fêted at the leading European courts, accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo for his mediation of the Treaty of Portsmouth, and delivered a series of lectures at leading European institutions, including his famous "man in the arena" speech at the Sorbonne. The New York Times wrote, "No foreign ruler or man of eminence could have aroused more universal attention, received a warmer welcome, or achieved greater popularity among every class of society."[7] He returned to the United States on June 18, 1910.

Party split

Payne-Aldrich tariff

As part of the 1908 platform, the party pledged itself to "tariff revision," which nearly all observers took to mean a reduction in the record-high rates under the Dingley Tariff of 1898. Instead, Senator Nelson Aldrich and Speaker of the House Joseph Gurney Cannon worked to pass the Payne-Aldrich tariff, which reduced rates on some imports but raised them on most.[8] Robert M. La Follette and Jonathan P. Dolliver, both members of the progressive faction, led the opposition to the tariff legislation in the U.S. Senate.[9] Taft, who studied under William Graham Sumner in college, opposed high tariffs.[10] He stated that Aldrich was "ready to sacrifice the party" and told La Follette that he would veto the legislation, but later gave his support to the legislation after meetings with Aldrich and Cannon.[11] He signed the bill into law on August 5, 1909.[12]

Taft, unlike his predecessor, refused to interfere with legislation through executive leverage, and his efforts at mediation between progressives and conservatives failed. Seizing on the plain meaning of "revision" in the 1908 platform, Aldrich questioned, "Where did we ever make the statement that we would revise the tariff downward?"[12] Though Taft had been a bystander in the tariff's passage, he defended it in a speaking tour soon after its passage into law. He said, "On the whole... I think the Payne bill is the best bill that the Republican Party ever passed."[12]

Pinchot-Ballinger controversy

One of the cabinet secretaries not retained by the Taft administration was James R. Garfield, a progressive and close advisor to Roosevelt. He was replaced by commissioner of the General Land Office Richard Ballinger. Within weeks of taking office, Ballinger privatized three million acres of federally preserved land, a reversal of Roosevelt's aggressive conservation policies.[13] Ballinger made a purely legalistic argument for the reversal, claiming that requisite data and congressional approval must be secured before public seizure of any land. Taft backed Ballinger in his insistence that conservation could only be pursued "on the basis of law."[14]

Ballinger's chief critic was his own subordinate, head of the United States Forestry Service Gifford Pinchot, who had overseen Roosevelt's conservation efforts from that office and had become Roosevelt's close personal friend. The Pinchot-Ballinger controversy soon became a proxy for several latent political conflicts—progressives versus conservatives, corporate interests versus public rights, East versus West—and consequently Pinchot's cause became the opening volley in the 1912 campaign to defeat Taft.[15] In August 1909, both men spoke at the National Irrigation Conference in Spokane. Pinchot "threw down the gauntlet" by stating "unequivocally" that a national hydropower trust was "in the process of formation," aided by "strict construction" of the law, which inevitably championed "the great interests as against the people."[16] Ballinger, under attack from Pinchot and the progressive press, merely recited a "routine dissertation on public-land matters."[14] He was the only speaker not to accept questions, which drew an open rebuke from California governor George Pardee.[14]

Immediately after his Spokane speech, Pinchot took his case directly to Taft, claiming that waterpower interests had begun an immense land grab in Montana.[14] Soon after, Pinchot and regional forestry official Louis Glavis additionally advised Taft that Ballinger had, as commissioner, obstructed antitrust investigations into a Seattle developer who later became his legal client. In September, Taft rejected their findings and publicly exonerated Ballinger of wrong-doing and criticized Glavis's zeal.[14] In January 1910, Pinchot took the case public in an open letter to Dolliver, after which Taft promptly fired him for insubordination.

Still in Africa, Roosevelt declined to publicly comment but privately wrote Pinchot, "I cannot believe it. I do not know any man in public life who has rendered quite the service you have rendered."[17] Separately, he wrote to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge that he would "say nothing about politics until I have been home long enough to know the situation" and that he believed the party "must renominate" Taft.[18] Nevertheless, public speculation mounted. Dolliver said, "With Pinchot knocked out and Aldrich put in command, I think you can hear a ."[19][page needed]

Pinchot met Roosevelt at Porto Maurizio on the latter's return journey through Europe, where he shared his and others' criticisms of the Taft administration.[18] Roosevelt then wrote to Lodge of his impression that the administration had "completely twisted round the policies I advocated and acted upon."[18]

Through the spring of 1910, as Roosevelt made his return from Europe, Congress held hearings into Taft's handling of the controversy.

Joseph Gurney Cannon

Taft personally disliked Cannon and discussed the idea of removing him from the speakership with Roosevelt shortly before ascending to the presidency. The declining Republican majority in the U.S. House of Representatives meant that the progressive faction of the Republicans could challenge Cannon by allying with the Democrats. Twelve Republican representatives refused to vote for Cannon in the 1909 speaker election. Cannon removed his opponents from committee posts and Taft declined to object to these actions.[20]

On August 5, 1909, Cannon announced the selection for the permanent committees. This selection removed progressives Charles N. Fowler, Augustus P. Gardner, and Henry Allen Cooper from their positions as committee chairs. This produced a progressive backlash and progressives organized candidates to primary Republican incumbents who supported Cannon and the Payne-Aldrich tariff.[21]

A poll by the Chicago Tribune in late 1909 showed that 80% of newspaper editors west of the Allegheny Mountains wanted Cannon removed. Lodge wrote to Roosevelt in November stating that there was an understanding that Cannon would not be reelected speaker of the 62nd United States Congress. Taft asked Knox to suggest in "certain Senatorial and other quarters" that this was the best time for Cannon to retire on his own volition.[22] In 1910, a proposal by Representative George W. Norris to greatly reduce the power of the speaker was approved by a vote of 191 to 156, with 46 Republicans in support. Cannon did not resign and a motion of dismissal by Representative Albert S. Burleson failed.[23] Cannon was replaced in Republican leadership by James Robert Mann as Minority Leader after the 1910 election.[24]

1910 elections

Taft gave a speech in Winona, Minnesota to defend Representative James A. Tawney and the Payne-Aldrich tariff. Historian George E. Mowry wrote that this speech as "a major milestone in the alienation of progressive Republican sentiment from the Taft administration".[25] The backlash to this speech and Taft's tour led to Lodge to write to Roosevelt about his concerns of La Follette and Cummins tearing the party apart. However, Taft was unaware of the internal disputes as he was surrounded by local leaders and wrote that his tour achieved everything he wanted in a letter to Secretary of State Philander C. Knox. Taft later told Attorney General George W. Wickersham that he may have been mistaken in defending Aldrich.[26]

Conservative and pro-Taft incumbents suffered multiple losses in the 1910 elections. Hiram Johnson was elected as governor of California, La Follette defeated his conservative primary opponent, and Miles Poindexter was elected to the U.S. Senate.[27]

Roosevelt's western trip and New Nationalism

If our political institutions were perfect, they would absolutely prevent the political domination of money in any part of our affairs. We need to make our political representatives more quickly and sensitively responsive to the people whose servants they are. ... The prime problem of our nation is to get the right type of good citizenship, and, to get it, we must have progress, and our public men must be genuinely progressive.

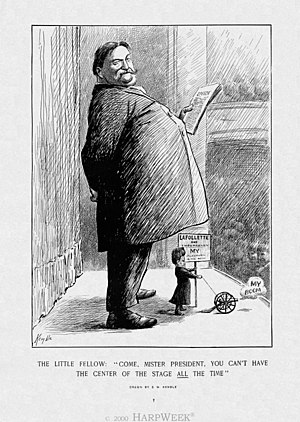

In advance of the New York convention, Roosevelt embarked on a western tour, ostensibly as an independent commentator for The Outlook. Some in the press already treated this as the start of a presidential campaign. "It is incredible that there should remain a single American citizen who does not see that Theodore Roosevelt has undertaken a campaign for the presidential nomination in 1912," wrote the New York Sun.[28] Speaking in Denver on August 29, Roosevelt delivered one of his first political speeches since leaving office, denouncing the Lochner v. New York decision and accusing the Supreme Court of favoring corporations over "popular rights."[28]

His trip culminated in a speech calling for a "new nationalism" in Osawatomie, Kansas on August 31.[29] The speech was drafted with advice from Pinchot, William Allen White, and Herbert Croly and by far the most radical he had ever delivered, calling for primacy of the executive, as "the steward of the public welfare" over the judiciary, which must be made "interested primarily in human welfare rather than in property." He also called for the large-scale revision of law "so as to work for a more substantial equality of opportunity and of reward for equally good service."[30]

National progressives praised the speech, while conservatives decried Roosevelt as a "new Napoleon," "neo-Populist," "peripatetic revolutionist," "a virtual traitor to American institutions."[30][28] The speech was declaimed as "more nearly revolutionary than anything that ever proceeded from the lips of any American who has held high office in our Government" and "more and worse than rank socialism—it is communism at the limit."[30][28] Privately, Roosevelt admitted to Lodge, "I had no business to take the position in the fashion that I did."[28]

Schism and New York convention

Republican politics in New York were divided between factions under the leadership of Governor Charles Evans Hughes and Timothy L. Woodruff. Woodruff's faction hampered Hughes' agenda and blocked Hughes' legislation for a direct presidential primary.[31] Roosevelt re-entered politics in his home state of New York, allying with Hughes to support these failed primary proposals.[32] To press the cause of electoral reform, Roosevelt stood for election as temporary chairman of the state convention. Taft offered to support Roosevelt and denounce Aldrich and Cannon, in exchange for an endorsement of the administration, but Roosevelt refused the deal. The New York Republican Party instead supported Vice President James S. Sherman for convention president, an implicit endorsement of the administration against the insurgents.[29][33]

Roosevelt met with Taft in New Haven, Connecticut.[34][29] Taft reiterated his willingness to support Roosevelt's bid for convention chair.[35] However, when Taft's secretary, Charles D. Norton, told the press that Roosevelt had begged for the meeting to boost his failing career, Roosevelt was privately incensed and denied the story, annoying Taft in turn.[35] Taft told Archibald Butt that he and Roosevelt had reached "the parting of the ways."[29]

As the summer wore on, Roosevelt and Taft's personal relationship deteriorated.[36] Relations between the "insurgents" and the regular Republicans deteriorated as well, as conservatives sought to purge the party of more radical Roosevelt allies like Senator Albert Beveridge, against whom Taft and the Republican Congressional Campaign Committee raised funds.[37]

At the end of September, Roosevelt personally appeared at the New York convention in Saratoga. There, delegates rallied to his support and elected him chair rather than Sherman, who had to escort him to the stage for his keynote address. Roosevelt denounced machine politics as "the negation of democracy".[35] The next day, the convention nominated Roosevelt's preferred candidate for governor, Henry Stimson, by a large margin.[29][35] When asked by Ray Stannard Baker soon after if he was a candidate for president, Roosevelt replied, "I don't know."[38]

Democratic landslide and aftermath

Roosevelt, in a letter to Lodge, wrote about internal Republican disputes aiding the Democrats in the 1910 election. This included criticizing Cannon's supporters who "would a thousand fold" prefer a Democratic victory rather than Cannon not being elected speaker. The New York Republican Party was in turmoil as progressives attacked Roosevelt for supporting Taft and the tariff while conservatives attacked him as using the state's gubernatorial election as a stepping stone to a presidential campaign in 1912.[39]

In the fall, Roosevelt campaigned for both progressive and conservative Republicans.[40] The Democratic Party gained a majority in the United States House of Representatives for the first time since 1895. Many of the Democratic victories were achieved by combining with progressive independents and Republicans to defeat conservatives, while many progressive Republicans retained their seats, heightening confidence that they could supplant Taft in 1912.[41] In the alternative, some saw the defeat of the Republican ticket in New York as a personal rebuke of Roosevelt.[42] Republicans lost several gubernatorial elections, including to Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson in New Jersey.[43]

Pre-campaign maneuvering

After the humiliating defeat of 1910, Roosevelt receded into private life and Taft turned his focus to the divided Congress, controlled by a mix of Democrats and insurgent Republicans. Roosevelt generally declined entreaties to challenge Taft, stating that the best hope for progressives was to "do what we can with Taft, face probable defeat in 1912, and then endeavor to reorganize under really capable and sanely progressive leadership."[44]

On January 21, 1911, the National Progressive Republican League was founded in La Follette's home.[45] Its charter membership boasted eight United States Senators (in addition to La Follette, Joseph L. Bristow, Moses E. Clapp, Norris, and Jonathan Bourne Jr., who served as president) and sixteen U.S. Representatives. La Follette asked Roosevelt to join the league, but he declined. Though most members professed to support Roosevelt, the organization was regarded as a vehicle for a La Follette campaign.[46] Similar organizations were formed in Minnesota, Michigan, Nebraska, South Dakota, Washington, and Wisconsin. Bourne stated that the 1912 presidential election would be between Wilson and La Follette.[47]

In March and April, Roosevelt completed a quiet tour of the American Southwest. While he publicly declined to comment on politics, he privately told friends Taft could only be renominated "by default," absent a serious progressive in the race. He did not regard La Follette, who struggled to attract support in the East, as that candidate.[48] Roosevelt made his first public criticism of Taft administration policy in a spring editorial for The Outlook denouncing international arbitration. In June, the two men made their final public appearance together in Baltimore; after Roosevelt denied subsequent reports that he had promised to support Taft in 1912, they did not speak for several years.[48]

Through the year, Taft's popularity sagged further. His efforts for tariff reciprocity with Canada had devolved into a prolonged struggle over rates and, though Congress eventually passed a compromise bill, the parallel debate north of the border resulted in the collapse of Wilfrid Laurier's government.[49] Roosevelt's editorial criticisms became more strident, though he privately admonished his son, who was becoming active in progressive politics, not to openly endorse a challenger. "My present intention," he wrote to Theodore Jr., "is to make a couple of speeches for Taft, but not to go actively into the campaign."[49]

U.S. Steel prosecution

In November, Roosevelt returned to the political stage to testify in front of a congressional committee investigating his oversight of the 1907 partial merger of U.S. Steel and the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company. He testified that his acquiescence to the merger had been necessary to halt the financial panic and generally acquitted himself well in the hearing, receiving praise even from the Democratic New York Times.[49]

Nevertheless, the Department of Justice opened an antitrust case against U.S. Steel, with Attorney General George Wickersham arguing the trust was monopolistic in intent. Though Wickersham argued that Roosevelt was innocent of wrongdoing, he suggested the former president had naïvely enabled U.S. Steel.[50] In response, Roosevelt defended his record and denounced the Taft antitrust agenda as "chaotic." Privately, he began speaking more openly about his willingness to challenge Taft. The response won praise on Wall Street, and the New York World suggested Roosevelt could be "Mr. Morgan's candidate for President."[50]

Procedure

The presidential nomination was decided by a simple majority vote of the delegates to the 1912 Republican National Convention. Unlike the Democratic Party of the time, the Republicans had no unit rule[d][e] or two-thirds majority requirement.

Delegate allocation

A total of 1,078 delegates were allocated for the convention.[1]

Roosevelt supporters criticized the allocation of a large amount of delegates to the South as essentially amounting to a system of rotten boroughs; over 200 delegates would come from states that had not been won by a Republican since the end of Reconstruction and where the party was essentially non-existent other than Republican appointees who owed their jobs to Taft. However, Roosevelt had previously rejected an attempt to abolish Southern delegations at the 1908 Republican National Convention, relying on their support and his own leverage over federal appointments to secure Taft's nomination.[51] Taft used his support from the southern delegates, 83% of which voted for him, to win the nomination.[52] Another twelve delegates came from the District of Columbia, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, which would not vote in the general election.

Selection process

The method of delegate selection in the various states was an early proxy contest between the progressives and the conservatives, with progressives favoring a direct primary process. Upon Roosevelt's entry into the race in late February 1912, his supporters lobbied for the adoption of direct primary laws in as many states as possible, believing that the existing convention system would be impassibly dominated by the conservatives.[2]

Despite the efforts of Taft supporters, primary elections were adopted by legislation in several states. In addition to the existing binding primary systems in place in California, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oregon, Wisconsin, and New Jersey, Roosevelt supporters successfully lobbied for primary legislation in Illinois, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, and South Dakota. Taft supporters were successful in blocking primary legislation in Michigan.[53]

In the South, the convention system remained dominant; party leaders dominated the proceedings and were in turn dominated by the federal administration. Party leaders were told their appointment power (and in some cases their own federal employment) would be withdrawn if they did not deliver their delegation to Taft.[53] Cecil Lyons, the chair of the Texas party, had his patronage power withdrawn over his support for Roosevelt.[53][54] Upon Roosevelt's entry, Taft operatives also made every effort accelerate the pace of the conventions, so that they could be held before Roosevelt had an opportunity to organize.[2] Roosevelt delegates to local and state conventions responded by frequently accusing the local party machine of corruption and illegitimacy, forming a rump convention, and electing a competing slate of delegates. This created a large number of delegate credential contests to be resolved at the national convention.

Candidates

Nominee

| Candidate | Most recent position | Home state | Campaign | Popular vote | Contests won | Running mate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Howard Taft |

|

President of the United States (1909–1913) |

|

(Campaign) Secured nomination: June 22, 1912 |

766,326 (33.9%) |

[data missing] | James S. Sherman | |

Withdrew during convention

| Candidate | Most recent position | Home state | Campaign | Popular vote | Contests won | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theodore Roosevelt |

|

President of the United States (1901–1909) |

|

(Campaign • Positions) Defeated at convention: June 22, 1912 (ran as Progressive) |

1,164,765 (51.5%) |

[data missing] | |

| Robert M. La Follette |

|

U.S. Senator from Wisconsin (1906–1925) |

|

327,357 (14.5%) |

[data missing] | ||

| Albert B. Cummins |

|

U.S. Senator from Iowa (1908–1926) |

|

— | [data missing] | ||

Campaign

Pre-primary campaign

In February 1910, a poll of Republican newspaper editors west of the Allegheny Mountains by the Chicago Tribune showed Roosevelt leading Taft by 300 votes. In April, Poindexter stated that only Roosevelt could win in 1912. In June, the president of Roosevelt Club of St. Paul, with Pinchot and James Rudolph Garfield in attendance, predicted the formation of a new political party under the leadership of Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Garfield.[55]

An attempt was made to have the Republican Party of Iowa endorse Taft for reelection at its 1910 convention, but it failed while delegates cheered at a picture of Roosevelt.[56]

La Follette announced his campaign on June 17, 1911.[57] His campaign was financially backed by Pinchot, William Kent, William Flinn, Charles Richard Crane, and Rudolph Spreckels (son of Claus Spreckels). He was unable to coalesce the progressive movement with Governor Walter R. Stubbs, U.S. Senator Albert J. Beveridge, and others refusing to support him. Cummins believed that La Follette would not receive more than 200 votes at the convention.[58]

As formal steps toward the primaries and conventions began in late 1911, La Follette was the sole declared challenger to President Taft; though he had the support of most progressives and insurgents, few observers considered him likely to win, even in the event that Taft was forced from the race at the convention.[59]

On November 21, Roosevelt's name was officially entered into the Nebraska primary.[citation needed] Unauthorized Roosevelt clubs were founded in Idaho, Montana, Michigan, and Ohio. In December, a group of three progressive state party chairmen, led by Frank Knox of Michigan, visited Roosevelt at Sagamore Hill; he again refused to run, but privately, his will had begun to waver.[59] He declined to issue a Sherman pledge and consulted with political allies through January on whether or not he should enter the race.[60] In December, governors Stubbs, Chase Osborn, and William E. Glasscock announced their support for a Roosevelt campaign.[61]

January: Delegate elections begin and LaFollette declines

On January 12, Roosevelt considered launching his campaign by replying to a joint letter of invitation by Robert P. Bass, Glasscock, Herbert S. Hadley, and Stubbs. These four governors had been urging him to run for the presidency, but the idea was almost abandoned when it was leaked. However, he continued with the idea after governors Osborn and Chester Hardy Aldrich also announced their support.[62]

On January 16, the Roosevelt National Committee was independently formed in Chicago; speculation became widespread that the former president would announce a campaign in late February, when he was scheduled to speak at the Ohio constitutional convention. He publicly stated that he would be willing to entertain a draft and would feel "in honor bound" if it came from the "plain people."[63][64]

There was an attempt to end La Follette's campaign by promising a Roosevelt-La Follette ticket. La Follette rejected this, but the Pinchots, who faced embarrassment if they switched to Roosevelt after publicly asking La Follette to run, unsuccessfully tried to convince him to withdraw. Many of La Follette supporters, including the Pinchots and Flinn, secretly contributed to Roosevelt while still campaigning for La Follette in January.[65]

Delegate selections began as early as January 23, when the district convention for Oklahoma's 4th congressional district devolved into anarchy; the local committee chair attempted a stampede for Roosevelt, complete with men in Rough Riders costumes, but was reminded that La Follette was Taft's only official challenger and repelled from the stage. After the convention voted 118–32 to endorse Taft over La Follette, the chairman went outside and detonated five hundred pounds of high explosives.[63]

February: The South solid for Taft

On February 2, Roosevelt privately told Johnson that he would run. That same night La Follette gave a disastrous speech to the Periodical Publishers Association in Philadelphia. La Follette, who had recently recovered from ptomaine poisoning, was deprived of sleep, and was distraught over a life-threatening operation to his daughter, devolved into a harangue of the newspapermen. His gave a confused speech in which he repeated himself constantly over the course of one hour. The next day the Pinchots, Flinn, Medill McCormick, and other La Follette supporters abandoned him for Roosevelt. A rumor spread that La Follette withdrew from the race when in fact he was taking a two-week break due to illness and overwork.[66][63]

The strategy of the Taft organization in the South, where they were assured of total control for the time being, was to hold conventions before Roosevelt could organize there, sometimes months before the usual time. The Taft campaign sought to quickly overpower Roosevelt-supporting party chairs, such as Cecil Lyons of Texas and Pearl Wright of Louisiana, and avoid the possibility that loyalty would evaporate if job-seekers came to believe that Taft could not be re-elected.[67] The Taft forces in the South were organized rapidly by William B. McKinley, with threats issued to state and local party leaders to return a Taft delegation or face removal from office.[67]

The Roosevelt organization, especially in the South, was ad hoc and poorly organized. In Oklahoma, for example, two competing Roosevelt campaign organs were established, each seeking to seize the novel authority of the insurgent campaign for their own. Eventually, the national Roosevelt campaign intervened to resolve the dispute. Similar local disputes elsewhere diverted the campaign's energy and focus during the early months.[68] To counter the Taft campaign, the Roosevelt forces sent a full-time staffer, Ormsby McHarg, to lobby Southern delegates. In Washington, pro-Roosevelt Senators blocked Taft's political appointments and opened a national investigation into the use of patronage in the South.[67]

On February 6, Florida Republicans held their state convention, which appeared to be organized solidly for Taft given his control of the party apparatus. After contested delegates were resolved in favor of the Taft forces, the Roosevelt men bolted to nominate a competing slate of Roosevelt delegates.[67][63] Thus, a tone was set for the Southern campaign; conventions would elect a Taft delegation and Roosevelt supporters would elect a competing slate of delegates.[67]

On February 10, the governors of Kansas, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, and West Virginia answered Roosevelt's call for a draft. Speaking at the Ohio convention on February 21, he called for recall of judicial decisions as a last resort, an indirect slight to Taft, a former federal judge from Ohio. "We should hold the judiciary in all respect, but it is both absurd and degrading to make a fetish of a judge or of any one else," he declared.[69] Amid furor and accusations of insanity from conservatives, legal scholars, and even some progressives, he formally accepted the draft petition in Boston on February 25.[69]

March 19: North Dakota

The first presidential preference primary was held in North Dakota on March 19. The North Dakota campaign was unique in that Roosevelt faced La Follette without Taft in the race. The state's progressive organization under Senator Asle Gronna committed to La Follette in 1911. The conservatives, led by L. B. Hanna, backed Roosevelt.[70]

Roosevelt attributed his loss to Democrats who voted for La Follette to embarrass his candidacy.[citation needed]

March 26: New York, Colorado, and Indiana

President Taft's first major victory came in New York's primary on March 26. Just before the vote, the New York Times reported that Taft had won 134 out of the 170 delegates chosen nationwide.[citation needed]

Both Roosevelt and former governor Charles Evans Hughes had aggressively campaigned for a direct primary in 1910 but were unsuccessful, possibly in part because Taft appointed Hughes to the U.S. Supreme Court during the campaign. Republicans lost the New York election in dramatic fashion, and under Democratic governor John Alden Dix in 1911, the state passed its first primary law. The Dix law did not satisfy progressives; the New York Legislative Voters Association said it could "scarcely be recognized by the name of direct primary." The legislature further amended the law in advance of the 1912 primary; the Citizens Union, a good government organization closely associated with Roosevelt during his time as governor, decried the amendments. "All the legislation enacted on the subject of primaries tended to make successful contests against the party machines even more difficult than under the unfair primary law enacted last year."[71]

The campaign for New York opened the night after the North Dakota primary, when Roosevelt spoke at Carnegie Hall. Noticing both William Barnes Jr. and Timothy L. Woodruff in the audience, Roosevelt framed his speech around the subject of boss rule. He received a standing ovation for declaring, "I prefer to govern myself, to do my own part, rather than have the government of a particular class."[72]

The primary was closed, meaning only voters who formally enrolled as members of the Republican Party could vote. In all cities of over 5,000 people, voters were required to enroll in advance, while same-day registration was permitted in smaller towns and villages. Polls were open from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., except in New York City, where polls did not open until 3 p.m. Votes were collected by secret ballot.[73]

Roosevelt supporters harshly criticized the conduct of the primary.[71] In New York City, the election board used a fourteen-foot-long ballot; at least one newspaper compared it to a hall runner for a city flat.[71] On some ballots, up to three feet of blank space separated the Roosevelt ticket from its emblem, leading some voters to tear off what the thought was waste paper and render their ballot unusable.[72] In at least 400 of the 1,069 election districts, the physical supply of ballots, tally sheets, or election officials were lacking such that no primary was held at all. On primary day, Roosevelt's New York campaign manager Charles Holland Duell telegraphed his complaint to Governor Dix, "An apter method of mocking the supposed right of the voter to signify his will at a party primary could not have been devised."[71]

The result was a landslide for Taft, with those able to vote turning out two-to-one for the President. In Roosevelt's native New York City, he won only a single delegate, who ran unopposed. Overall, he received seven delegates to Taft's eighty-three. Progressives won no party committee races at any level.[72] Taft also swept the Colorado and Indiana conventions held that same night.[72]

After the results came in, Roosevelt himself joined the criticism of the New York process, which he called "fraud."[72] He likewise denounced the "brutal and indecent" exclusion of his delegates in Indiana and "outrageous" tactics in Denver. "They are stealing the primary elections from us," he said. "All I ask is a square deal. ... I cannot and will not stand by while the opinion of the people is being suppressed and their will thwarted."[72] His campaign strategy changed to emphasize in-person speeches, and he implicitly threatened to bolt the party if not nominated at the convention.[72]

April 9–19: Roosevelt surges

Roosevelt's fortunes began to change with the Illinois primary on April 9. In his first primary victory, Roosevelt won 61% of the vote to Taft 29% and La Follette 10%. Roosevelt won every county, though Taft won some Congressional Districts in Chicago.

In the two weeks following the Illinois primary, Roosevelt won three states. He defeated Taft by a 60-40% margin in Pennsylvania on April 13. Nebraska and Oregon voted on April 19, going to Roosevelt with 59% and 40% respectively.

April 30: Massachusetts

Taft ended the month with a 50–48% win in Massachusetts. However, due to the Massachusetts ballot offering a presidential preference separate from the delegate vote, Roosevelt won more delegates even though he placed second. By the end of the month, Roosevelt was leading in delegates chosen in primaries with 179 to 108 for Taft and 36 for La Follette. Due to the fact that just 14 states held primaries, Taft had 428 delegates overall while Roosevelt had 204 and La Follette had 36.

Post-primary maneuvering

A big turn of events occurred on June 17, 1912. The Chicago Tribune sent out a newspaper with a column on the Republican primary titled, "10 From South Desert Taft for Roosevelt". In this column the writer explains that five Mississippi delegates and five Georgia delegates announced that they would not be supporting Taft in this second presidential election, but instead would switch their support to Theodore Roosevelt. All ten of the delegates signed a statement that they were deserting the Taft movement and supporting Roosevelt. The Taft campaign marked up the southern states and their delegates in anticipation of a big southern win. This changed when the five Georgia delegates, Clark, Grier, J.H. Boone, J. C. Styles, J. Eugene Peterson, and S. S. Mincey switched to supporting Roosevelt along with the five Mississippi delegates Charles Banks, W.P. Locker, Perry W. Howard, Daniel W. Gerry, and Wesly Crayton.[75]

Theodore Roosevelt also attacked President Taft in the Chicago Tribune on June 17, 1912, with his own column. In the column Roosevelt wrote about the differences in delegates that Taft and he had. He stated that the delegates Taft had were from territories or states that had never cast a Republican electoral vote or were controlled by federal patronage. Roosevelt summed up Taft's delegates as, "one-eighth of his delegates represent a real sentiment for him and seven-eighths represent nothing whatever but the use of patronage in his interest in certain Democratic states". Roosevelt made it clear that Taft had turned the Republican Party for the worst and that he had no chance of winning the election.[76]

Five states voted in the final four weeks of the primary season, and Roosevelt won all five states. He won Maryland 53–47 over Taft. In California, Roosevelt received 55% to Taft's 27% and La Follette's 18%. The major shock of the primary season was Roosevelt's 55–40% defeat of Taft in his home state of Ohio on May 21. One week later, Roosevelt won New Jersey, 56–41%. The primary season wrapped up with South Dakota, where Roosevelt won with 55%.

Schedule and results

| Date (daily totals) |

Total pledged delegates |

Contest and total popular vote |

Delegates won and popular vote | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Taft | Theodore Roosevelt | Robert M. La Follette | Other | Reference | |||||||

| January 23 | 2 | Oklahoma 4th convention |

2 118 (78.7%) |

32 (21.3%) |

— | [77][78] | |||||

| February 6 | 4 | Florida convention |

[f] | [g] | [79][80] | ||||||

| March 14 | ? | Oklahoma convention |

? | 16[h] | [81] | ||||||

| March 19 | 10 | North Dakota primary |

0 1,876 |

4 23,669 |

6 34,123 |

[82] | |||||

| March 25 | 2 | Michigan 12th convention |

2 | – | – | [83] | |||||

| March 26 | 90 | New York primary[i] |

59 (66.43%) |

31 (33.57%) |

0 0% |

[82] | |||||

| ? | Colorado convention |

? ? |

? |

[84] | |||||||

| ? | Indiana convention |

? ? |

? |

[84] | |||||||

| April 2 | 26 | Wisconsin primary |

7 47,514 |

0 628 |

19 133,354 |

0 643 |

[82] | ||||

| April 9 | 58 | Illinois primary |

19 127,481 |

39 266,917 |

0 42,692 |

[82] | |||||

| April 13 | 76 | Pennsylvania primary |

31 191,179 |

45 282,853 |

0 0 |

[82] | |||||

| April 19 (27) |

17 | Nebraska primary |

3 13,341 |

10 45,795 |

4 16,785 |

0 2,036 |

[82] | ||||

| 10 | Oregon primary |

3 20,517 |

4 28,905 |

3 22,491 |

0 14 |

[82] | |||||

| April 30 | 36 | Massachusetts primary |

18 86,722 |

18 83,099 |

0 2,058 |

0 99 |

[82] | ||||

| May 5–28[j] | 40 | Texas conventions |

5[k] | 5[k] | — | – | [85] | ||||

| May 6 | 16 | Maryland primary |

8 25,995 |

8 29,124 |

0 0 |

[82] | |||||

| May 14 | 26 | California primary |

7 69,345 |

14 138,563 |

5 45,876 |

[82] | |||||

| May 21 | 48 | Ohio primary |

20 118,362 |

28 165,809 |

0 15,570 |

[82] | |||||

| May 28 | 28 | New Jersey primary |

12 44,034 |

16 61,297 |

0 3,464 |

[86] | |||||

| June 4 | 11 | South Dakota primary |

3 19,960 |

6 38,106 |

2 10,944 |

[86] | |||||

| Total 388 pledged delegates 2,311,036 votes |

|||||||||||

Endorsements

This article is missing information about endorsements. (March 2022) |

- U.S. Executive Branch officials

James Rudolph Garfield, former U.S. Secretary of the Interior(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)[87]Gifford Pinchot, former Chief of the United States Forest Service(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)[87]

- U.S. Senators

Jonathan Bourne Jr., U.S. Senator from Washington(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)[88]

- U.S. Representatives

George W. Norris, U.S. Representative from Nebraska(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)

- Journalists

Medill McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)[87]

- Individuals

William Flinn, chairman of the Pennsylvania Republican State Committee(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)[89]Amos Pinchot, attorney, activist, and brother of Gifford Pinchot(switched endorsement to Roosevelt)[87]

- U.S. Executive Branch officials

- James Rudolph Garfield, former U.S. Secretary of the Interior[87]

- Truman Newberry, former U.S. Secretary of the Navy[87]

- Gifford Pinchot, former Chief of the United States Forest Service[87]

- U.S. Senators

- Albert Beveridge, former U.S. Senator from Indiana[88]

- William Borah, U.S. Senator from Idaho[88]

- Jonathan Bourne Jr., U.S. Senator from Washington[88]

- Joseph L. Bristow, U.S. Senator from Kansas[88]

- Moses E. Clapp, U.S. Senator from Minnesota[88]

- Joseph M. Dixon, U.S. Senator from Montana[88]

- U.S. Representatives

- Victor Murdock, U.S. Representative from Kansas[88]

- George W. Norris, U.S. Representative from Nebraska

- Governors

- Robert P. Bass, Governor of New Hampshire[77]

- William E. Glasscock, Governor of West Virginia[77]

- Herbert S. Hadley, Governor of Missouri[90]

- Hiram Johnson, Governor of California[91]

- Francis E. McGovern, Governor of Wisconsin

- Chase Osborn, Governor of Michigan[77]

- Walter R. Stubbs, Governor of Kansas[77]

- Statewide officials

- Timothy Woodruff, former Lieutenant Governor of New York[92]

- Journalists

- Henry Justin Allen, publisher of the Manhattan Nationalist and Topeka State Journal[93]

- O.K. Davis, former reporter for The New York Times[87]

- Frank Knox, founding editor of the Manchester Leader[87]

- Medill McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune[87]

- Frank Munsey, publisher of the Washington Times, Boston Journal, and New York Press[87]

- William Allen White, editor of the Emporia Gazette[88]

- Individuals

- William Flinn, chairman of the Pennsylvania Republican State Committee[94]

- Francis J. Heney, former prosecutor from San Francisco and Oregon[94]

- Amos Pinchot, attorney, activist, and brother of Gifford Pinchot[87]

- George Walbridge Perkins, business aide to J.P. Morgan[95]

- Alexander Revell, millionaire furniture retailer[87]

- U.S. Senators

- W. Murray Crane, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts[94]

- Boies Penrose, U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania[94]

- U.S. Representatives

- Augustus Peabody Gardner, U.S. Representative from Massachusetts[93]

- James Eli Watson, former U.S. Representative from Indiana[96]

- Governors

- Beryl F. Carroll, Governor of Iowa[97]

- Adolph Olson Eberhart, Governor of Minnesota[97]

- Phillips Lee Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland[97]

- Marion E. Hay, Governor of Washington[97]

- Ben Hooper, Governor of Tennessee[97]

- John Tener, Governor of Pennsylvania[97]

- William Spry, Governor of Utah[97]

- Simeon S. Pennewill, Governor of Delaware[97]

- Aram J. Pothier, Governor of Rhode Island[97]

- Statewide officials

- Warren Harding, former Lieutenant Governor of Ohio[98]

- Individuals

- William Barnes Jr., chairman of the New York Republican State Committee[99]

- U.S. Senators

- Albert Cummins, U.S. Senator from Iowa and favorite son

- Henry Cabot Lodge, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts[100]

Convention

Delegations from the south acted as rotten boroughs due to their size despite having no influence in elections. An attempt to reduce their influence failed in 1908, with Roosevelt having fought against it. The southern delegations, whose 252 delegates accounted for almost half of the number needed to win the nomination, almost entirely supported Taft.[101]

388 delegates were selected through the primaries and Roosevelt won 281, Taft received 71 delegates, and La Follette received 36 delegates. However, Taft had a 566–466 margin, placing him over the 540 needed for nomination, with the delegations selected at state conventions. Roosevelt accused the Taft faction of having over 200 fraudulently selected delegates. However, the Republican National Committee ruled in favor of Taft for 233 of the delegate cases while 6 were in favor of Roosevelt. The committee reinvestigated 92 of the contested delegates and ruled in favor of Taft for all of them.[102][103]

Herbert S. Hadley served as Roosevelt's floor manager at the convention. Hadley made a motion for 74 of Taft's delegates to be replaced by 72 delegates after the reading of the convention call, but his motion was ruled out of order. Elihu Root, a supporter of Taft, was selected to chair the convention after winning 558 votes against McGovern's 501 votes. Root was accused of having won through the rotten boroughs of the southern delegations as every northern state, except for four, voted for McGovern.[102] Hadley was later proposed as a compromise candidate, but that attempt was unsuccessful. James Eli Watson and other conservative Republicans considered Hadley's candidacy, but William Barnes Jr., Boies Penrose, and Root opposed it as losing the convention would result in the destruction of the Old Guard's political machine.[104][page needed]

Warren G. Harding presented Taft's name for the nomination. Taft won the nomination while 344 of Roosevelt's delegates abstained from the vote. Allen read a speech from Roosevelt in which he criticized the process and stated that delegates had been stolen from his in order to secure Taft's nomination. Later that day supporters of Roosevelt met in the Chicago Orchestra Hall and nominated him as an independent candidate for president which Roosevelt accepted although he requested a formal convention. Roosevelt initially considered not running as a third-party candidate until George Walbridge Perkins and Frank Munsey offered their financial support. Roosevelt and his supporters formed the Progressive Party and Johnson was selected as his vice-presidential running mate.[102]

See also

References

- ^ a b Chace 2004, p. 113.

- ^ a b c Morris 2010, p. 176.

- ^ Gould 1976, p. 33.

- ^ Kalb, Deborah (2016-02-19). Guide to U.S. Elections - Google Books. CQ Press. ISBN 9781483380353. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ Gould 1976, p. 44.

- ^ Chace 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Goodwin 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Chace 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 45.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Chace 2004, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Ganoe, John T. (September 1934), "Some Constitutional and Political Aspects of the Ballinger–Pinchot Controversy", The Pacific Historical Review, 3 (3): 323–333, doi:10.2307/3633711, JSTOR 3633711

- ^ a b c d e Goodwin 2013, pp. 607–14.

- ^ Goodwin 2013, p. 606.

- ^ Goodwin 2013, pp. 607–09.

- ^ Chace 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Chace 2004, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Wayne 2008.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 164.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b c d e f Morris 2010, pp. 106–09.

- ^ a b c d e Chace 2004, pp. 55–61.

- ^ a b c Goodwin 2013, pp. 643–46.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Morris 2010, pp. 94–100.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 139.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d Morris 2010, pp. 113–16.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Goodwin 2013, p. 650.

- ^ Chace 2004, p. 94.

- ^ Goodwin 2013, pp. 651–52.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 155.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 122.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 172.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, pp. 136–37.

- ^ a b c Morris 2010, pp. 143–45.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, pp. 149–52.

- ^ Mowry 1946, p. 241.

- ^ Black & Black 1992, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Chace 2004, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Gould 1976.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 118.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 128.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 174.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, pp. 152–54.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Mowry 1960, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d Morris 2010, pp. 163–66.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 205.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 206.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 207.

- ^ a b c d e Mowry 1946, pp. 226–28.

- ^ Mowry 1946, pp. 226–27.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, pp. 168–70.

- ^ Mowry 1946, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d Feldman 1917, p. 495.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morris 2010, pp. 179–83.

- ^ Feldman 1917, pp. 496–97.

- ^ Mowry 1946, p. 229.

- ^ "10 FROM SOUTH DESERT TAFT FOR ROOSEVELT (June 17, 1912)." June 17, 1912 - 10 FROM SOUTH DESERT TAFT FOR ROOSEVELT | Chicago Tribune Archive. N.p., 17 June 1912. Web. 21 Feb. 2017.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore. "Roosevelt Delegates, Taft Delegates, Stolen Delegates. (June 17, 1912)." June 17, 1912 - Roosevelt Delegates, Taft Delegates, Stolen Delegates. | Chicago Tribune Archive. N.p., 17 June 1912. Web. 21 Feb. 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Morris 2010, p. 164.

- ^ "Ed Perry Down and Out: Spectacular Politician Met Waterloo in Coalgate Convention--Taft Endorsed". The Choctaw Herald. 25 Jan 1912. p. 1. Retrieved 4 Jun 2023.

- ^ Mowry 1946, p. 226.

- ^ "Plenty of Work For National Committee: Republican Rump Convention in Florida is the Starter; Advantage is With Taft". The Indianapolis News. 7 Feb 1912. p. 3. Retrieved 4 Jun 2023.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Congressional Quarterly 1997, p. 149.

- ^ "Twelfth Michigan for Taft". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Ishpeming, Mi. 26 Mar 1912. p. 2. Retrieved 4 Jun 2023.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, p. 181.

- ^ Gould 1976, p. 45.

- ^ a b Congressional Quarterly 1997, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Morris 2010, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Morris 2010, p. 173.

- ^ Mowry 1960, p. 202.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 165.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 207.

- ^ a b Morris 2010, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Morris 2010, p. 192.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Review of Week's Political Game". The Bowling Green Daily Sentinel-Tribune. 4 Mar 1912. p. 1.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 209.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 174.

- ^ Sherman 1973, pp. 79, 102.

- ^ a b c Nash 1959.

- ^ "TAFT 566 - ROOSEVELT 466. - Present Line-Up of Instructed and Pledged Delegates With All the Contests Decided" (PDF). New York Times. 1912-06-16. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ^ Murphy 1974.

Notes

- ^ At the convention, a large number of Roosevelt delegates abstained from voting. For the purposes of the roll call map, their votes are combined with those who cast their vote for Roosevelt.

- ^ a b At the end of the selection process, 254 delegates were in dispute between Roosevelt and Taft. These numbers reflect the undisputed totals.[3]

- ^ Roosevelt had been elected Vice President in 1900, become President in 1901 upon the assassination of William McKinley, and been re-elected to a full term of his own in 1904.

- ^ a.k.a. "winner-take-all" rule, requiring that all delegates vote in accordance with the majority of their state

- ^ The Democratic Party ultimately repealed their unit rule at the 1912 convention.

- ^ All four Florida delegates were contested between Roosevelt and Taft.

- ^ All four Florida delegates were contested between Roosevelt and Taft.

- ^ Roosevelt won ten statewide delegates and six district delegates elected simultaneously.

- ^ Primary held, but vote figures are not known.

- ^ The Texas precinct conventions were held on May 5, followed by county conventions on May 8 and district conventions at some intermediate date, culminating in a state convention on May 28. Delegates were elected at the district and state level.[54]

- ^ a b The remainder of the Texas delegates were contested between Roosevelt and Taft.

Works cited

- Black, Earl; Black, Merle (1992). The Vital South: How Presidents Are Elected. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674941306.

- Evans, Gary (1997). Presidential Elections: 1789-1996. Congressional Quarterly. ISBN 1568020651.

- Mowry, George (1960). Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Sherman, Richard (1973). The Republican Party and Black America From McKinley to Hoover 1896-1933. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813904676.

Further reading

Books

- Chace, James (2004). 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft, and Debs—The Election That Changed the Country. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0394-1.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2013). The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-416-54786-0.

- Mowry, George E. (1946). "Chapter Eight: Old Friends are Friends No Longer". Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement. New York: Hill and Wang. pp. 220–55.

- Murphy, Paul (1974). Political Parties In American History, Volume 3, 1890-present. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Nash, Howard P. (1959). "Chapter Nine: Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement". Third Parties in American Politics. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press. pp. 242–267.

- Wayne, Stephen (2008). Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process Fifth Edition. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Wilensky, Norman N. (1965). Conservatives in the Progressive Era: The Taft Republicans of 1912. Gainesville.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Primary sources

- Davis, Oscar King (1925). Released for Publication: Some Inside Political History of Theodore Roosevelt and His Times, 1898–1918. Boston. pp. 292–313.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (Roosevelt perspective) - Rosewater, Victor (1932). Backstage in 1912: The Inside Story of the Split Republican Convention. Philadelphia. pp. 80–185.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (Taft perspective)

Candidate biographies

- Harbaugh, William Henry (1961). Power and Responsibility: The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. New York. pp. 412–36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Morris, Edmund (2010). Colonel Roosevelt. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50487-7.

- Pringle, Henry F. (1939). The Life and Times of William Howard Taft. Vol. II. New York. pp. 765–814.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Articles

- Feldman, H. (August 1917). "The Direct Primary in New York State". The American Political Science Review. 11 (3): 494–518. doi:10.2307/1944250. JSTOR 1944250. S2CID 147503477.

- Gould, Lewis L. (July 1976). "Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Disputed Delegates in 1912: Texas as a Case Study". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 80 (1): 33–56. JSTOR 30238426.

- Kraig, Robert Alexander (Fall 2000). "The 1912 Election and the Rhetorical Foundations of the Liberal State". Rhetoric and Public Affairs. 3 (3): 363–95. doi:10.1353/rap.2010.0042. JSTOR 41940243. S2CID 143817140.

- Overacker, Louise (March 1923). "The Operation of the State-Wide Direct Primary in New York State". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 106, The Direct Primary: 142–47. doi:10.1177/000271622310600116. JSTOR 1014670. S2CID 143733897.

- Pavord, Andrew C. (Summer 1996). "The Gamble for Power: Theodore Roosevelt's Decision to Run for the Presidency in 1912". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3, Reassessments of Presidents and First Ladies): 633–47. JSTOR 27551622.

- Strange, Douglas C. (November 1968). "The Making of a President—1912: The Northern Negroes' View". Negro History Bulletin. 31 (7): 14–23. JSTOR 24767265.

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !