Rudolf Vrba

Rudolf Vrba | |

|---|---|

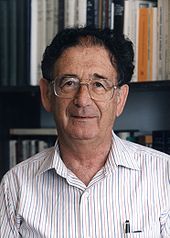

Vrba in New York, November 1978, during an interview with Claude Lanzmann for the documentary Shoah | |

| Born | Walter Rosenberg 11 September 1924 |

| Died | 27 March 2006 (aged 81) Vancouver, Canada |

| Citizenship | British (1966), Canadian (1972) |

| Education |

|

| Occupation(s) | Associate professor of pharmacology, University of British Columbia |

| Known for | Vrba–Wetzler report[1] |

| Spouse(s) |

Gerta Vrbová (m. 1947)Robin Vrba (m. 1975) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

Rudolf Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg; 11 September 1924 – 27 March 2006) was a Slovak-Jewish biochemist who, as a teenager in 1942, was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in German-occupied Poland. He escaped from the camp in April 1944, at the height of the Holocaust, and co-wrote the Vrba-Wetzler report, a detailed report about the mass murder taking place there.[2] The report, distributed by George Mantello in Switzerland, is credited with having halted the mass deportation of Hungary's Jews to Auschwitz in July 1944, saving more than 200,000 lives. After the war, Vrba trained as a biochemist, working mostly in England and Canada.[3]

Vrba and his fellow escapee Alfréd Wetzler fled Auschwitz three weeks after German forces invaded Hungary and shortly before the SS began mass deportations of Hungary's Jewish population to the camp. The information the men dictated to Jewish officials when they arrived in Slovakia on 24 April 1944, which included that new arrivals in Auschwitz were being gassed and not "resettled" as the Germans maintained, became known as the Vrba–Wetzler report.[1] When the War Refugee Board published it with considerable delay in November 1944, the New York Herald Tribune described it as "the most shocking document ever issued by a United States government agency".[4] While it confirmed material in earlier reports from Polish and other escapees,[a] the historian Miroslav Kárný wrote that it was unique in its "unflinching detail".[9]

There was a delay of several weeks before the report was distributed widely enough to gain the attention of governments. Mass transports of Hungary's Jews to Auschwitz began on 15 May 1944 at a rate of 12,000 people a day.[10] Most went straight to the gas chambers. Vrba argued until the end of his life that the deportees might have refused to board the trains, or at least that their panic would have disrupted the transports, had the report been distributed sooner and more widely.[11]

From late June and into July 1944, material from the Vrba–Wetzler report appeared in newspapers and radio broadcasts in the United States and Europe, particularly in Switzerland, prompting world leaders to appeal to Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy to halt the deportations.[12] On 2 July, American and British forces bombed Budapest, and on 6 July, in an effort to exert his sovereignty, Horthy ordered that the deportations should end.[13] By then, over 434,000 Jews had been deported in 147 trains—almost the entire Jewish population of the Hungarian countryside—but another 200,000 in Budapest were saved.[b]

Early life and arrest

Vrba was born Walter Rosenberg on 11 September 1924 in Topoľčany, Czechoslovakia (part of Slovakia from 1993), one of the four children of Helena Rosenberg, née Gruenfeldová, and her husband, Elias. Vrba's mother was from Zbehy;[16] his maternal grandfather, Bernat Grünfeld, an Orthodox Jew from Nitra, was murdered in the Majdanek concentration camp.[17] Vrba took the name Rudolf Vrba after his escape from Auschwitz.[18]

The Rosenbergs owned a steam sawmill in Jaklovce and lived in Trnava.[19] In September 1941 the Slovak Republic (1939–1945)—a client state of Nazi Germany—passed a "Jewish Codex", similar to the Nuremberg Laws, which introduced restrictions on Jews' education, housing and travel.[20] The government set up transit camps at Nováky, Sereď and Vyhne.[21] Jews were required to wear a yellow badge and live in certain areas, and available jobs went first to non-Jews. When Vrba was excluded, at age 15, from the gymnasium (high school) in Bratislava as a result of the restrictions, he found work as a labourer and continued his studies at home, particularly chemistry, English and Russian.[22] He met his future wife, Gerta Sidonová, around this time; she had also been excluded from school.[23]

Vrba wrote that he learned to live with the restrictions but rebelled when the Slovak government announced, in February 1942, that thousands of Jews were to be deported to "reservations" in German-occupied Poland.[24][c] The deportations came at the request of Germany, which needed the labour; the Slovak government paid the Germans RM 500 per Jew on the understanding that the government would lay claim to the deportees' property.[26] Around 800 of the 58,000 Slovak Jews deported between March and October 1942 survived.[27] Vrba blamed the Slovak Jewish Council for having cooperated with the deportations.[28]

Insisting that he would not be "deported like a calf in a wagon", Vrba decided to join the Czechoslovak Army in exile in England and set off in a taxi for the border, aged 17, with a map, a box of matches, and the equivalent of £10 from his mother.[29] After making his way to Budapest, Hungary, he decided to return to Trnava but was arrested at the Hungarian border.[30] The Slovak authorities sent him to the Nováky transit camp; he escaped briefly but was caught. An SS officer instructed that he be deported on the next transport.[31]

Majdanek and Auschwitz

Majdanek

Vrba was deported from Czechoslovakia on 15 June 1942 to the Majdanek concentration camp in Lublin, German-occupied Poland,[32] where he briefly encountered his older brother, Sammy. They saw each other "almost simultaneously and we raised our arms in brief salute"; it was the last time he ever saw him.[33] He also encountered "kapos" for the first time: prisoners appointed as functionaries, one of whom he recognized from Trnava. Most wore green triangles, signalling their category as "career criminals":[34]

They were dressed like circus clowns ... One had a green uniform jacket with gold horizontal stripes, like something a lion tamer would wear; his trousers were the riding breeches of an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army and his headgear was a cross between a military cap and a priest's biretta. ... I realized that here was a new elite ... recruited to do the elementary dirty work with which the S.S. men did not wish to soil their hands.[34]

Vrba's head and body were shaved, and he was given a uniform, wooden shoes and a cap. Caps had to be removed whenever the SS came within three yards. Prisoners were beaten for talking or moving too slowly. At roll call each morning, prisoners who had died during the night were piled up behind the living. Vrba was given a job as a builder's labourer.[35] When a kapo asked for 400 volunteers for farm work elsewhere, Vrba signed up, looking for a chance to escape. A Czech kapo who had befriended Vrba hit him when he heard about this; the kapo explained that the "farm work" was in Auschwitz.[36]

Auschwitz I

On 29 June 1942, the Reich Security Main Office transferred Vrba and the other volunteers to Auschwitz I,[37] the main camp (Stammlager) in Oświęcim, a journey of over two days. Vrba considered trying to escape from the train, but the SS announced that ten men would be shot for every one who went missing.[38]

On his second day in Auschwitz, Vrba watched as prisoners threw bodies onto a cart, stacked in piles of ten, "the head of one between the legs of another to save space".[39] The following day he and 400 other men were beaten into a cold shower in a shower room built for 30, then marched outside naked to register. He was tattooed on his left forearm as no. 44070 and given a striped tunic, trousers, cap and wooden shoes.[40] After registration, which took all day and into the evening, he was shown to his barracks, an attic in a block next to the main gate and the Arbeit macht frei sign.[41]

Young and strong, Vrba was "purchased" by a kapo, Frank, in exchange for a lemon (sought after for its vitamin C) and assigned to work in the SS food store. This gave him access to soap and water, which helped to save his life. Frank, he learned, was a kind man who would pretend to beat his prisoners when the guards were watching, although the blows always missed.[42] The camp regime was otherwise marked by its pettiness and cruelty. When Heinrich Himmler visited on 17 July 1942 (during which he watched a gassing), the inmates were told everything had to be spotless.[43] As the prison orchestra assembled by the gate for Himmler's arrival, the block senior and two others started beating an inmate because he was missing a tunic button:

They pummeled him swiftly, frantically, trying to blot him out ... and Yankel, who had forgotten to sew his buttons on, had not even the good grace to die quickly and quietly.

He screamed. It was a strong, querulous scream, ragged in the hot, still air. Then it turned suddenly to the thin, plaintive wail of abandoned bagpipes ... It went on and on and on ... At that moment, I think, we all hated Yankel Meisel, the little old Jew who was spoiling everything, who was causing trouble for all of us with his long, lone, futile protest.[44]

Auschwitz II

"Kanada" commando

In August 1942 Vrba was reassigned to the Aufräumungskommando ("clearing-up") or "Kanada" commando, in Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the extermination camp, 4 km (2.5 miles) from Auschwitz I. Around 200–800 prisoners worked on the nearby Judenrampe where freight trains carrying Jews arrived, removing the dead, then sorting through the new arrivals' property. Many brought kitchen utensils and clothes for different seasons, suggesting to Vrba that they believed the stories about resettlement.[45]

It took 2–3 hours to clear out a train, by which time most new arrivals were dead.[45] Those deemed fit for work were selected for slave labour and the rest taken by truck to the gas chamber.[46] Vrba estimated that 90 percent were gassed.[47] He told Claude Lanzmann in 1978 that the process relied on speed and making sure no panic broke out, because panic meant the next transport would be delayed.[48]

[O]ur first job was to get into the wagons, get out the dead bodies—or the dying—and transport them in laufschritt, as the Germans liked to say. This means "running". Laufschritt, yeah, never walking—everything had to be done in laufschritt, immer laufen. ... There was not much medical counting to see who is dead and who feigns to be dead ... So they were put on the trucks; and once this was finished, this was the first truck to move off, and it went straight to the crematorium ..

The whole murder machinery could work on one principle: that the people came to Auschwitz and didn't know where they were going and for what purpose. The new arrivals were supposed to be kept orderly and without panic marching into the gas chambers. Especially the panic was dangerous from women with small children. So it was important for the Nazis that none of us give some sort of message which could cause a panic ... And anybody who tried to get in touch with newcomers was either clubbed to death or taken behind the wagon and shot ...[49]

The new arrivals' property was taken to barracks known as Effektenlager I and II in Auschwitz I (moved to Auschwitz II after Vrba's escape). Inmates, and apparently also some of the camp administration, called the barracks Kanada I and II because they were a "land of plenty".[50] Everything was there—medicine, food, clothing, and cash—much of it repackaged by the Aufräumungskommando to be sent to Germany.[51] The Aufräumungskommando lived in Auschwitz I, block 4, until 15 January 1943 when they were transferred to block 16 in Auschwitz II, sector Ib, where Vrba lived until June 1943.[52]

After Vrba had been in Auschwitz for about five months, he fell sick with typhus; his weight dropped to 42 kilograms (93 lb) and he was delirious. At his lowest point, he was helped by Josef Farber, a Slovak member of the camp resistance, who brought him medication and thereafter extended to him the protection of the Auschwitz underground.[53]

In early 1943 Vrba was given the job of assistant registrar in one of the blocks; he told Lanzmann that the resistance movement had manoeuvered him into the position because it gave him access to information.[54] A few weeks later, in June, he was made registrar (Blockschreiber) of block 10 in Auschwitz II, the quarantine section for men (BIIa), again because of the underground.[55] The position gave him his own room and bed,[56] and he could wear his own clothes. He was also able to speak to new arrivals who had been selected to work, and he had to write reports about the registration process, which allowed him to ask questions and take notes.[57]

Estimates of numbers murdered

From his room in BIIa, Vrba said he could see the trucks drive toward the gas chambers.[58] In his estimate, 10 percent of each transport was selected to work and the rest murdered.[47] During his time on the Judenrampe from 18 August 1942 to 7 June 1943, he told Lanzmann in 1978, he had seen at least 200 trains arrive, each containing 1,000–5,000 people.[59] In a 1998 paper, he wrote that he had witnessed 100–300 trains arrive, each locomotive pulling 20–40 freight cars and sometimes 50–60.[45] He calculated that, between the spring of 1942 and 15 January 1944, 1.5 million had been murdered.[60] According to the Vrba–Wetzler report, 1,765,000 were murdered in Auschwitz between April 1942 and April 1944.[61] In 1961 Vrba swore in an affidavit for the trial of Adolf Eichmann that he believed 2.5 million had been murdered overall in the camp, plus or minus 10 percent.[62]

Vrba's estimates are higher than those of Holocaust historians but in line with estimates from SS officers and Auschwitz survivors, including members of the Sonderkommando. Early estimates ranged from one to 6.5 million.[63] Rudolf Höss, the first Auschwitz commandant, said in 1946 that three million had been murdered in the camp, although he revised his view.[64] In 1946 the Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland estimated four million.[65] Later scholarly estimates were lower. According to Polish historian Franciszek Piper, writing in 2000, most historians place the figure at one to 1.5 million.[66] His own widely accepted estimate was that at least 1.3 million were sent to Auschwitz and at least 1,082,000 died (rounded up to 1.1 million or 85 percent), including 960,000 Jews.[67] Piper's estimate of the death toll for April 1942 to April 1944 was 450,000,[68] against Vrba's 1,765,000.[69]

Hungarian Jews

According to Vrba, a kapo from Berlin by the name of Yup told him on 15 January 1944 that he was part of a group of prisoners building a new railway line to lead straight to the crematoria. Yup said he had overheard from an SS officer that a million Hungarian Jews would soon arrive and that the old ramp could not handle the numbers. A railway line leading directly to the crematoria would cut thousands of truck journeys from the old ramp.[70] In addition Vrba heard directly, courtesy of drunk SS guards, he wrote, that they would soon have Hungarian salami. When Dutch Jews arrived, they brought cheese; likewise there were sardines from the French Jews, and halva and olives from the Greeks. Now it was Hungarian salami.[71]

Vrba had been thinking of escaping for two years but, he wrote, he was now determined, hoping to "undermine one of the principal foundations—the secrecy of the operation".[72] A Soviet captain, Dmitri Volkov, told him he would need Russian tobacco soaked in petrol, then dried, to fool the dogs; a watch to use as a compass; matches to make food; and salt for nutrition.[73] Vrba began studying the layout of the camps. Both Auschwitz I and II consisted of inner camps where the prisoners slept, surrounded by a six-yard-wide trench of water, then high-voltage barbed-wire fences. The area was lit at night and guarded by the SS in watchtowers. When a prisoner was reported missing, the guards searched for three days and nights. The key to a successful escape would be to remain hidden just outside the inner perimeter until the search was called off.[74]

His first escape was planned for 26 January 1944 with Charles Unglick, a French Army captain, but the rendezvous did not work out; Unglick tried to escape alone and was killed. The SS left his body on display for two days, seated on a stool.[75] An earlier group of escapees had been killed and mutilated with dumdum bullets, then placed in the middle of Camp D with a sign reading "We're back!"[76]

Czech family camp

On 6 March 1944 Vrba heard that the Czech family camp was about to be sent to the gas chambers.[77] The group of around 5,000, including women and children, had arrived in Auschwitz in September 1943 from the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. That they had been allowed to live in Auschwitz for six months was unusual, not least because women with children were usually murdered immediately. Correspondence found after the war between Adolf Eichmann's office and the International Red Cross suggested that the Germans had set up the family camp as a model for a planned Red Cross visit to Auschwitz.[78] The group was housed in relatively good conditions in block BIIb near the main gate, although in the six months they were held there 1,000 died despite the better treatment.[79] They did not have their heads shaved, and the children were given lessons and access to better food, including milk and white bread.[80]

On 1 March, according to the Vrba–Wetzler report (5 March, according to Danuta Czech), the group was asked to write postcards to their relatives, telling them they were well and asking for parcels of provisions, and to postdate the cards to 25–27 March.[81] On 7 March, according to the report (8–9 March, according to Czech), the group of 3,791 was gassed.[82] The report stated that 11 twins had been kept alive for medical experiments.[83] On 20 December 1943, a second Czech family group of 3,000 arrived, according to the report (2,473, according to Czech).[84] Vrba assumed that this group would also be murdered after six months, i.e. around 20 June 1944.[85]

Escape

Vrba resolved again to escape. In Auschwitz he had encountered an acquaintance from Trnava, Alfréd Wetzler (prisoner no. 29162, then aged 26) who had arrived on 13 April 1942 and was working in the mortuary.[86] Czesław Mordowicz, who escaped from Auschwitz weeks after Vrba, said decades later that it was Wetzler who had initiated and planned the escape.[87]

According to Wetzler, writing in his book Čo Dante nevidel (1963), later published as Escape from Hell (2007), the camp underground had organized the escape, supplying information for Vrba and Wetzler to carry ("Karol" and "Val" in the book). "Otta" in Hut 18, a locksmith, had created a key for a small shed in which Vrba and others had drawn a site plan and dyed clothes. "Fero" from the central registry supplied data from the registry;[88] "Filipek" (Filip Müller) in Hut 13 added the names of the SS officers working around the crematoria, a plan of the gas chambers and crematoria, his records of the transports gassed in crematoria IV and V, and the label of a Zyklon B canister.[89] "Edek" in Hut 14 smuggled out clothes for the escapees to wear, including suits from Amsterdam.[88] "Adamek", "Bolek" and Vrba had supplied socks, underpants, shirts, a razor and a torch, as well as glucose, vitamins, margarine, cigarettes and a cigarette lighter that said "made in Auschwitz".[90]

The information about the camp, including a sketch of the crematorium produced by a Russian prisoner, "Wasyl", was hidden inside two metal tubes. The tube containing the sketch was lost during the escape; the second tube contained data about the transports. Vrba's account differs from Wetzler's; according to Vrba, they took no notes and wrote the Vrba–Wetzler report from memory.[91] He told the historian John Conway that he had used "personal memotechnical methods" to remember the data, and that the stories about written notes had been invented because no one could explain his ability to recall so much detail.[92]

Wearing suits, overcoats, and boots, at 14:00 on Friday, 7 April 1944—the eve of Passover—the men climbed inside a hollowed-out space they had prepared in a pile of wood stacked between Auschwitz-Birkenau's inner and outer perimeter fences, in section BIII in a construction area known as "Meksyk" ("Mexico"). They sprinkled the area with Russian tobacco soaked in gasoline, as advised by Dmitri Volkov, the Russian captain, to ward off dogs.[93] Bolek and Adamek, both Polish prisoners, moved the planks back in place once they were hidden.[94]

Kárný writes that at 20:33 on 7 April SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Hartjenstein, the Birkenau commander, learned by teleprinter that two Jews were missing.[95] On 8 April the Gestapo at Auschwitz sent telegrams with descriptions to the Reich Security Head Office in Berlin, the SS in Oranienburg, district commanders, and others.[96] The men hid in the wood pile for three nights and throughout the fourth day.[97] Soaking wet, with strips of flannel tightened across their mouths to muffle coughing, Wetzler wrote that they lay there counting: "[N]early eighty hours. Four thousand eight hundred minutes. Two hundred and eighty-eight thousand seconds."[98] On Sunday morning, 9 April, Adamek urinated against the pile and whistled to signal that all was well.[99] At 9 pm on 10 April, they crawled out of the wood pile. "Their circulation returns only slowly," Wetzler wrote. "They both have the sensation of ants running along in their veins, that their bodies have been transformed into big, very slowly warming ant-heaps. ... The onset of weakness is so fierce that they have to support themselves on the inner edges of the panels."[100] Using a map they'd taken from "Kanada", the men headed south toward Slovakia 130 kilometres (81 mi) away, walking parallel to the Soła river.[101]

Vrba–Wetzler report

Walking to Slovakia

According to Henryk Świebocki of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, local people, including members of the Polish underground who lived near the camp, did what they could to help escapees.[102] Vrba wrote that there was no organized help for them on the outside. At first the men moved only at night, eating bread taken from Auschwitz and drinking from streams. On 13 April, lost in Bielsko-Biala, they approached a farmhouse and a Polish woman took them in for a day. Feeding them bread, potato soup and ersatz coffee, she explained that most of the area had been "Germanized" and that Poles helping Jews risked death.[103]

They continued following the river; every so often, a Polish woman would drop half a loaf of bread near them. They were shot at on 16 April by German gendarmes but escaped. Two other Poles helped them with food and a place to stay, until they finally crossed the Polish–Slovak border near Skalité on 21 April 1944.[104] By this time, Vrba's feet were so swollen he had had to cut off his boots and was wearing carpet slippers one of the Polish peasants had given him.[105]

A peasant family in Skalité took them in for a few days, fed and clothed them, then put them in touch with a Jewish doctor in nearby Čadca, Dr. Pollack. Vrba and Pollack had met in a transit camp in Nováky.[106] Through a contact in the Slovak Jewish Council, Pollack arranged for them to send people from Bratislava to meet the men.[107] Pollack was distressed to learn the probable fate of his parents and siblings, who had been deported from Slovakia to Auschwitz in 1942.[108]

Meeting with the Jewish Council

Vrba and Wetzler spent the night in Čadca in the home of a relative of the rabbi Leo Baeck, before being taken to Žilina by train. They were met at the station by Erwin Steiner, a member of the Slovak Jewish Council (or Ústredňa Židov), and taken to the Jewish Old People's Home, where the council had offices. Over the following days, they were introduced to Ibolya Steiner, who was married to Erwin; Oskar Krasniansky, an engineer and stenographer (who later took the name Oskar Isaiah Karmiel);[109] and, on 25 April, the chair of the council, Dr. Oskar Neumann, a lawyer.[110]

The council was able to confirm who Vrba and Wetzler were from its deportation lists.[111] In his memoir, Wetzler described (using pseudonyms) several people who attended the first meeting: a lawyer (presumably Neumann), a factory worker, a "Madame Ibi" (Ibolya Steiner) who had been a functionary in a progressive youth organization, and the Prague correspondent of a Swiss newspaper. Neumann told them the group had been waiting two years for someone to confirm the rumours they had heard about Auschwitz. Wetzler was surprised by the naïveté of his question: "Is it so difficult to get out [of] there?" The journalist wanted to know how they had managed it, if it was so hard. Wetzler felt Vrba lean forward angrily to say something, but he grabbed his hand and Vrba drew back.[112]

Wetzler encouraged Vrba to start describing conditions in Auschwitz. "He wants to speak like a witness," Wetzler wrote, "nothing but facts, but the terrible events sweep him along like a torrent, he relives them with his nerves, with every pore of his body, so that after an hour he is completely exhausted."[113] The group, in particular the Swiss journalist, seemed to have difficulty understanding. The journalist wondered why the International Red Cross had not intervened. "The more [Vrba] reports, the angrier and more embittered he becomes."[114] The journalist asked Vrba to tell them about "specific bestialities by the SS men". Vrba replied: "That is as if you wanted me to tell you of a specific day when there was water in the Danube."[115]

Vrba described the ramp, selection, the Sonderkommando, and the camps' internal organization; the building of Auschwitz III and how Jews were being used as slave labour for Krupp, Siemens, IG Farben, and DAW; and the gas chambers.[116] Wetzler gave them the data from the central registry hidden in the remaining tube, and described the high death toll among Soviet POWs, the destruction of the Czech family camp, the medical experiments, and the names of doctors involved in them.[117] He also handed over the label from the Zyklon B canister.[118] Every word, he wrote, "has the effect of a blow on the head".[119]

Neumann said the men would be brought a typewriter in the morning, and the group would meet again in three days. Hearing this, Vrba exploded: "Easy for you to say 'in three days'! But back there they are flinging people into the fire at this moment and in three days they'll kill thousands. Do something immediately!" Wetzler pulled on his arm, but Vrba continued, pointing at each one: "You, you, you'll all finish up in the gas unless something is done! Do you hear?"[120]

Writing the report

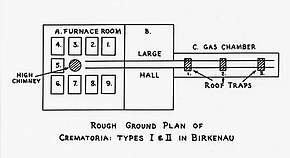

The following day, Vrba began by sketching the layout of Auschwitz I and II, and the position of the ramp in relation to the camps. The report was rewritten several times over three days;[121] according to Wetzler, on two of those days, he and Vrba wrote until daybreak.[120] Wetzler wrote the first part, Vrba the third, and they worked on the second part together. Then they re-wrote it six times. Oskar Krasniansky translated it from Slovak into German as it was being written, with the help of Ibolya Steiner, who typed it up. The original Slovak version is lost.[121] The report in Slovak and, it seems, in German was completed by Thursday, 27 April 1944.[122]

According to Kárný, the report describes the camp "with absolute accuracy", including its construction, installations, security, the prisoner number system, the categories of prisoner, the diet and accommodation, as well as the gassings, shootings and injections. It provides details known only to prisoners, including that discharge forms were filled out for prisoners who were gassed, indicating that death rates in the camp were falsified. Although presented by two men, it was clearly the product of many prisoners, including the Sonderkommando working in the gas chambers.[123] It contains sketches of the gas chambers and states that there were four crematoria, each of which contained a gas chamber and furnace room.[124] The report estimated the total capacity of the gas chambers to be 6,000 daily.[125]

[T]he unfortunate victims are brought into hall (B) where they are told to undress. To complete the fiction that they are going to bathe, each person receives a towel and a small piece of soap issued by two men clad in white coats. They are then crowded into the gas chamber (C) in such numbers that there is, of course, only standing room. To compress this crowd into the narrow space, shots are often fired to induce those already at the far end to huddle still closer together. When everybody is inside, the heavy doors are closed. Then there is a short pause, presumably to allow the room temperature to rise to a certain level, after which SS men with gas masks climb on the roof, open the traps, and shake down a preparation in powder form out of tin cans labeled 'CYKLON' 'For use against vermin', which is manufactured by a Hamburg concern. It is presumed that this is a 'CYANIDE' mixture of some sort which turns into gas at a certain temperature. After three minutes everyone in the chamber is dead.[126]

In a sworn deposition for the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, Vrba said that he and Wetzler had obtained the information about the gas chambers and crematoria from Sonderkommando Filip Müller and his colleagues who worked there. Müller confirmed this in his Eyewitness Auschwitz (1979).[127] The Auschwitz scholar Robert Jan van Pelt wrote in 2002 that the description contains errors, but that given the circumstances, including the men's lack of architectural training, "one would become suspicious if it did not contain errors".[128]

Distribution and publication

Rosin and Mordowicz escape

The Jewish Council found an apartment for Vrba and Wetzler in Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš, Slovakia, where the men kept a copy of the Vrba–Wetzler report, in Slovak, hidden behind a picture of the Virgin Mary. They made clandestine copies with the help of a friend, Josef Weiss of the Bratislava Office for the Prevention of Venereal Disease, and handed them out to Jews in Slovakia with contacts in Hungary, for translation into Hungarian.[129]

According to the historian Zoltán Tibori Szabó, the report was first published in Geneva in May 1944, in German, by Abraham Silberschein of the World Jewish Congress as Tatsachenbericht über Auschwitz und Birkenau, dated 17 May 1944.[130] Florian Manoliu of the Romanian Legation in Bern took the report to Switzerland and gave it to George Mantello, a Jewish businessman from Transylvania, who was working as the first secretary of the El Salvador consulate in Geneva. It was thanks to Mantello that the report received, in the Swiss press, its first wide coverage.[131]

Arnošt Rosin (prisoner no. 29858) and Czesław Mordowicz (prisoner no. 84216) escaped from Auschwitz on 27 May 1944 and arrived in Slovakia on 6 June, the day of the Normandy landings. Hearing about the invasion of Normandy and believing the war was over, they got drunk to celebrate, using dollars they had smuggled out of Auschwitz. They were arrested for violating the currency laws, and spent eight days in prison before the Jewish Council paid their fines.[132]

Rosin and Mordowicz were interviewed, on 17 June, by Oskar Krasniansky, the engineer who had translated the Vrba–Wetzler report into German. They told him that, between 15 and 27 May 1944, 100,000 Hungarian Jews had arrived at Auschwitz II-Birkenau and that most had been murdered on arrival.[133] Vrba concluded from this that the Hungarian Jewish Council had not informed its Jewish communities about the Vrba–Wetzler report.[134] The seven-page Rosin-Mordowicz report was combined with the longer Vrba–Wetzler report and a third report, known as the Polish Major's report (written by Jerzy Tabeau, who had escaped from Auschwitz in November 1943), to become the Auschwitz Protocols.[135]

According to David Kranzler, Mantello asked the Swiss-Hungarian Students' League to make 50 mimeographed copies of the Vrba–Wetzler report and the two shorter Auschwitz reports, which by 23 June 1944 he had distributed to the Swiss government and Jewish groups.[136] On or around 19 June Richard Lichtheim of the Jewish Agency in Geneva, who had received a copy of the report from Mantello, cabled the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem to say they knew "what has happened and where it has happened" and that 12,000 Jews were being deported from Budapest daily. He also reported the Vrba–Wetzler figure that 90 per cent of Jews arriving at Auschwitz II were being murdered.[137]

The Swiss students made thousands of copies, which were passed to other students and MPs.[136] At least 383 articles about Auschwitz appeared in the Swiss press between 23 June and 11 July 1944.[138] According to Michael Fleming, this was more than the number of articles published about the Holocaust during the war by all the British popular newspapers combined.[139]

Importance of dates

The dates on which the report was distributed became a matter of importance within Holocaust historiography. According to Randolph L. Braham, Jewish leaders were slow to distribute the report, afraid of causing panic.[140] Braham asks: "Why did the Jewish leaders in Hungary, Slovakia, Switzerland and elsewhere fail to distribute and publicize the Auschwitz Reports immediately after they had received copies in late April or early May 1944?"[141] Vrba alleged that lives were lost because of this. In particular he blamed Rudolf Kastner of the Budapest Aid and Rescue Committee.[142] The committee had organized safe passage for Jews into Hungary before the German invasion.[143] The Slovak Jewish Council handed Kastner the report at the end of April or by 3 May 1944 at the latest.[140]

Reverend József Éliás, head of the Good Shepherd Mission in Hungary, said he received the report from Géza Soós, a member of the Hungarian Independence Movement, a resistance group.[144] Yehuda Bauer believes that Kastner or Ottó Komoly, leader of the Aid and Rescue Committee, gave Soós the report.[145] Éliás's secretary, Mária Székely, translated it into Hungarian and prepared six copies, which made their way to Hungarian and church officials, including Miklós Horthy's daughter-in-law, Countess Ilona Edelsheim-Gyulai.[146] Braham writes that this distribution occurred before 15 May.[147]

| Part of a series of articles on the Holocaust |

| Blood for goods |

|---|

|

Kastner's reasons for not distributing the report further are unknown. According to Braham, "Hungarian Jewish leaders were still busy translating and duplicating the Reports on June 14–16, and did not distribute them till the second half of June. [They] almost completely ignored the Reports in their postwar memoirs and statements."[148] Vrba argued until the end of his life that Rudolf Kastner withheld the report in order not to jeopardize negotiations between the Aid and Rescue Committee and Adolf Eichmann, the SS officer in charge of the transport of Jews out of Hungary. As the Vrba–Wetzler report was being written, Eichmann had proposed to the Committee in Budapest that the SS trade up to one million Hungarian Jews for 10,000 trucks and other goods from the Western Allies. The proposal came to nothing, but Kastner collected donations to pay the SS to allow over 1,600 Jews to leave Budapest for Switzerland on what became known as the Kastner train. In Vrba's view, Kastner suppressed the report in order not to alienate the SS.[149]

The Hungarian biologist George Klein worked as a secretary for the Hungarian Jewish Council in Síp Street, Budapest, when he was a teenager. In late May or early June 1944, his boss, Dr. Zoltán Kohn, showed him a carbon copy of the Vrba–Wetzler report in Hungarian and said he should tell only close family and friends.[150] Klein had heard Jews mention the term Vernichtungslager (extermination camp), but it had seemed like a myth. "I immediately believed the report because it made sense," he wrote in 2011. " ... The dry, factual, nearly scientific language, the dates, the numbers, the maps and the logic of the narrative coalesced into a solid and inexorable structure."[151] Klein told his uncle, who asked how Klein could believe such nonsense: "I and others in the building in Síp Street must have lost our minds under the pressure." It was the same with other relatives and friends: middle-aged men with property and family did not believe it, while the younger ones wanted to act. In October that year, when the time came for Klein to board a train to Auschwitz, he ran instead.[152]

News coverage

Details from the Vrba–Wetzler report began to appear elsewhere in the media. On 4 June 1944 the New York Times reported on the "cold-blooded murder" of Hungary's Jews.[153] On 16 June the Jewish Chronicle in London ran a story by Isaac Gruenbaum of the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem with the headline "Bomb death camps"; the writer had clearly seen the Vrba–Wetzler report.[154] On the same date, in Germany, the BBC World Service reported the murder in March of the Czech family camp and the second Czech group the Vrba–Wetzler report said would be killed around 20 June.[155] The broadcast alluded to the Vrba–Wetzler report:

In London, there is a highly precise report on the mass murder in Birkenau. All of those responsible for this mass murder, from those who give the orders through their intermediaries and down to those who carry out the orders, will be held responsible.[156]

A 22-line story on page five of the New York Times, "Czechs report massacre", reported on 20 June that 7,000 Jews had been "dragged to gas chambers in the notorious German concentration camps at Birkenau and Oświęcim [Auschwitz]".[157] Walter Garrett, the Swiss correspondent of the Exchange Telegraph, a British news agency, sent four dispatches to London on 24 June with details from the report received from George Mantello, including Vrba's estimate that 1,715,000 Jews had been murdered.[158] As a result of his reporting, at least 383 articles about Auschwitz appeared over the following 18 days, including a 66-page report in Geneva, Les camps d'extermination.[159]

On 26 June the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported that 100,000 Hungarian Jews had been executed in gas chambers in Auschwitz. The BBC repeated this on the same day but omitted the name of the camp.[160] The following day, as a result of the information from Walter Garrett, the Manchester Guardian published two articles. The first said that Polish Jews were being gassed in Auschwitz and the second: "Information that the Germans systematically exterminating Hungarian Jews has lately become more substantial." The report mentioned the arrival "of many thousands of Jews ... at the concentration camp at Oswiecim".[161] On 28 June the newspaper reported that 100,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported to Poland and gassed, but without mentioning Auschwitz.[162]

Daniel Brigham, the New York Times correspondent in Geneva, published a story on 3 July, "Inquiry Confirms Nazi Death Camps", with the subtitle "1,715,000 Jews Said to Have Been Put to Death by the Germans up to April 15", and on 6 July a second, "Two Death Camps Places of Horror; German Establishments for Mass Killings of Jews Described by Swiss".[163] According to Fleming, the BBC Home Service mentioned Auschwitz as an extermination camp for the first time on 7 July 1944. It said that over "four hundred thousand Hungarian Jews [had been] sent to the concentration camp at Oświęcim" and that most were murdered in gas chambers; it added that the camp was the largest concentration camp in Poland and that gas chambers had been installed in 1942 that could murder 6,000 people a day. Fleming writes that the report was the last of nine on the 9 pm news.[164]

Meetings with Martilotti and Weissmandl

At the request of the Slovak Jewish Council,[165] Vrba and Czesław Mordowicz (one of the 27 May escapees), along with a translator and Oskar Krasniasnky, met Vatican Swiss legate Monsignor Mario Martilotti at the Svätý Jur monastery on 20 June 1944.[166] Martilotti had seen the report and questioned the men about it for five hours.[167] Mordowicz was irritated by Vrba during this meeting. In an interview in the 1990s for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, he said Vrba, 19 at the time, had behaved cynically and childishly; at one point he appeared to mock the way Martilotti was cutting his cigar. Mordowicz feared that the behaviour would make their information less credible. To maintain Martilotti's attention, he told him that Catholics and priests were being murdered along with the Jews. Martilotti reportedly fainted, shouting "Mein Gott! Mein Gott!"[168] Five days later, Pope Pius XII sent a telegram appealing to Miklós Horthy.[169]

Also at the Jewish Council's request, Vrba and Mordowicz met Michael Dov Weissmandl, an Orthodox rabbi and one of the leaders of the Bratislava Working Group, at his yeshiva in the centre of Bratislava. Vrba writes that Weissmandl was clearly well informed and had seen the Vrba–Wetzler report. He had also seen, as Vrba found out after the war, the Polish major's report about Auschwitz.[170] Weissmandl asked what could be done. Vrba explained: "The only thing to do is to explain ... that they should not board the trains ...".[171] He also suggested bombing the railway lines into Birkenau.[172] (Weissmandl had already suggested this, on 16 May 1944, in a message to the American Orthodox Jewish Rescue committee.)[173] Vrba wrote about the incongruity of visiting Weissmandl at his yeshiva, which he assumed was under the protection of the Slovak government and the Germans. "The visibility of yeshiva life in the center of Bratislava, less than 150 miles [240 km] south of Auschwitz, was in my eyes a typical piece of Goebbels–inspired activity .... There—before the eyes of the world—the pupils of Rabbi Weissmandel could study the rules of Jewish ethics while their own sisters and mothers were being murdered and burned in Birkenau."[172]

Deportations halted

Several appeals were made to Horthy, including by the Spanish, Swiss and Turkish governments, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gustaf V of Sweden, the International Committee of the Red Cross and, on 25 June 1944, Pope Pius XII.[174] The Pope's telegram did not mention Jews: "We are being beseeched in various quarters to do everything in our power that, in this noble and chivalrous nation, the sufferings, already so heavy, endured by a large number of unfortunate people, because of their nationality or race, may not be extended and aggravated."[139]

John Clifford Norton, a British diplomat in Bern, cabled the British government on 27 June with suggestions for action, which included bombing government buildings in Budapest. On 2 July American and British forces did bomb Budapest, killing 500[175] and dropping leaflets warning that those responsible for the deportations would be held to account.[176] Horthy ordered an end to the mass deportations on 6 July, "deeply impressed by Allied successes in Normandy", according to Randolph Braham,[177] and anxious to exert his sovereignty over the Germans in the face of threats of a pro-German coup.[13] According to Raul Hilberg, Horthy may also have been worried about information cabled by the Allies in Bern to their governments at the request of the Budapest Aid and Rescue Committee, informing them of the deportations. The cables were intercepted by the Hungarian government, which may have feared that its own members would be held responsible for the murders.[178]

War Refugee Board publication

The Vrba–Wetzler report received widespread coverage in the United States and elsewhere when, after many months delay, John Pehle of the US War Refugee Board issued a 25,000-word press release on 25 November 1944,[d] along with a full version of the report and a preface calling it "entirely credible".[180] Entitled The Extermination Camps of Auschwitz (Oświęcim) and Birkenau in Upper Silesia, the release included the 33-page Vrba–Wetzler report; a six-page report from Arnost Rosin and Czesław Mordowicz, who escaped from Auschwitz on 27 May 1944; and the 19-page Polish major's report, written in December 1943 by Polish escapee Jerzy Tabeau.[1] Jointly the three reports came to be known as the Auschwitz Protocols.[181]

The Washington Times Herald said the press release was "the first American official stamp of truth to the myriad of eyewitness stories of the mass massacres in Poland",[182] while the New York Herald Tribune called the Protocols "the most shocking document ever issued by a United States government agency".[4] Pehle passed a copy to Yank magazine, an American armed-forces publication, but the story, by Sergeant Richard Paul, was turned down as "too Semitic"; the magazine did not want to publish it, they said, because of "latent antisemitism in the Army".[183] In June 1944 Pehle had urged John J. McCloy, US assistant secretary of war, to bomb Auschwitz, but McCloy had said it was "impracticable". After the publication of the Protocols, he tried again. McCloy replied that the camp could not be reached by bombers stationed in France, Italy or the UK, which meant that heavy bombers would have to fly to Auschwitz, a journey of 2,000 miles, without an escort. McCloy told him: "The positive solution to this problem is the earliest possible victory over Germany."[184]

After the report

Resistance activities

After dictating the report in April 1944, Vrba and Wetzler stayed in Liptovský Mikuláš for six weeks, and continued to make and distribute copies of the report with the help of a friend, Joseph Weiss. Weiss worked for the Office for Prevention of Venereal Diseases in Bratislava and allowed copies to be made in the office.[185] The Jewish Council gave Vrba papers in the name of Rudolf Vrba, showing Aryan ancestry going back three generations,[18] and supported him financially with 200 Slovak crowns per week, equivalent to an average worker's salary; Vrba wrote that it was "sufficient to sustain me underground in Bratislava".[186] On 29 August 1944 the Slovak Army rose up against the Nazis and the reestablishment of Czechoslovakia was announced. Vrba joined the Slovak partisans in September 1944 and was later awarded the Czechoslovak Medal of Bravery.[187][188]

Auschwitz was liberated by the 60th Army of the 1st Ukrainian Front (part of the Red Army) on 27 January 1945; 1,200 prisoners were found in the main camp and 5,800 in Birkenau. The SS had tried to destroy the evidence, but the Red Army found what was left of four crematoria, as well as 5,525 pairs of women's shoes, 38,000 pairs of men's, 348,820 men's suits, 836,225 items of women's clothing, large numbers of carpets, utensils, toothbrushes, eyeglasses and dentures, and seven tons of hair.[189]

Marriage and education

Gerti and Rudi Vrba, Bratislava

In 1945 Vrba reconnected with a childhood friend, Gerta Sidonová, from Trnava. They both wanted to study for degrees, so they took courses set up by Czechoslovakia's Department of Education for those who had missed out on schooling because of the Nazis. They moved after that to Prague, where they married in 1947; Sidonová took the surname Vrbová, the female version of Vrba. She graduated in medicine, then went into research.[190] In 1949 Vrba obtained a degree in chemistry (Ing. Chem.) from the Czech Technical University in Prague, which earned him a postgraduate fellowship from the Ministry of Education, and in 1951 he received his doctorate (Dr. Tech. Sc.) for a thesis entitled "On the metabolism of butyric acid".[191][192] The couple had two daughters: Helena (1952–1982)[193] and Zuzana (b. 1954).[194] Vrba undertook post-doctoral research at the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, where he received his C.Sc. in 1956. From 1953 to 1958 he worked for Charles University Medical School in Prague.[191] His marriage ended around this time.[195]

Defection to Israel, move to England

With the marriage over and Czechoslovakia ruled by a Soviet Union-dominated socialist government, Vrba and Vrbová both defected, he to Israel and she to England with the children. Vrbová had fallen in love with an Englishman and was able to defect after being invited to an academic conference in Poland. Unable to obtain visas for her children, she returned illegally to Czechoslovakia and walked her children back over the mountains to Poland. From there they flew to Denmark with forged papers, then to London.[196]

In 1957 Vrba became aware, when he read Gerald Reitlinger's The Final Solution (1953), that the Vrba–Wetzler report had been distributed and had saved lives; he had heard something about this in or around 1951, but Reitlinger's book was the first confirmation.[197] The following year he received an invitation to an international conference in Israel, and while there, he defected.[188] For the next two years, he worked at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot.[198][191] He later said that he had been unable to continue living in Israel because the same men who had, in his view, betrayed the Jewish community in Hungary were now in positions of power there.[188] In 1960 he moved to England, where he worked for two years in the Neuropsychiatric Research Unit in Carshalton, Surrey, and seven years for the Medical Research Council.[199] He became a British subject by naturalization on 4 August 1966.[200]

Testimony

Trial of Adolf Eichmann

On 11 May 1960 Adolf Eichmann was captured by the Mossad in Buenos Aires and taken to Jerusalem to stand trial. (He was sentenced to death in December 1961.) Vrba was not called to testify because the Israeli Attorney General had apparently wanted to save the expense.[201] Because Auschwitz was in the news, Vrba contacted the Daily Herald in London,[202] and one of their reporters, Alan Bestic, wrote up his story, which was published in five installments over one week, beginning on 27 February 1961 with the headline "I Warned the World of Eichmann's Murders."[202] In July 1961 Vrba submitted an affidavit to the Israeli Embassy in London, stating that, in his view, 2.5 million had been murdered in Auschwitz, plus or minus 10 percent.[203]

Trial of Robert Mulka, book publication

Vrba testified against Robert Mulka of the SS at the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, telling the court that he had seen Mulka on the Judenrampe at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The court found that Vrba "made an excellent and intelligent impression" and would have been particularly observant at the time because he was planning to escape. It ruled that Mulka had indeed been on the ramp, and sentenced him to 14 years in prison.[204]

Following the Herald articles, Bestic helped to write Vrba's memoir, I Cannot Forgive (1963), also published as Factory of Death (1964). Bestic's writing style was criticized; reviewing the book, Mervyn Jones wrote in 1964 that it has the flavour of "the juicy bit on page 63".[205] Erich Kulka criticized the book in 1985 for minimizing the role played by the other three escapees (Wetzler, Mordowicz and Rosin); Kulka also disagreed with Vrba regarding his criticism of Zionists, the Slovak Jewish Council, and Israel's first president.[206] The book was published in German (1964), French (1988), Dutch (1996), Czech (1998) and Hebrew (1998).[191][207] It was republished in English in 1989 as 44070: The Conspiracy of the Twentieth Century and in 2002 as I Escaped from Auschwitz.[208]

Move to Canada, Claude Lanzmann interview

Interviewing Rudolf Vrba (video),

New York, November 1978

Vrba moved to Canada in 1967, where he worked for the Medical Research Council of Canada from 1967 to 1973,[191] becoming a Canadian citizen in 1972. From 1973 to 1975 he was a research fellow at Harvard Medical School, where he met his second wife, Robin Vrba,[209] originally from Fall River, Massachusetts.[210] They married in 1975 and returned to Vancouver, where she became a real-estate agent and he an associate professor of pharmacology at the University of British Columbia. He worked there until the early 1990s, publishing over 50 research papers on brain chemistry, diabetes, and cancer.[209]

Claude Lanzmann interviewed Vrba in November 1978, in New York's Central Park, for Lanzmann's nine-and-a-half-hour documentary on the Holocaust, Shoah (1985); the interview is available on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHHM).[211] The film was first shown in October 1985 at the Cinema Studio in New York.[212] A quote from Vrba's interview is inscribed on a USHMM exhibit:

Constantly, people from the heart of Europe were disappearing, and they were arriving to the same place with the same ignorance of the fate of the previous transport. I knew ... that within a couple of hours after they arrived there, ninety percent would be gassed.[213]

Trial of Ernst Zündel

Vrba testified in January 1985, along with Raul Hilberg, at the seven-week trial in Toronto of the German Holocaust denier Ernst Zündel.[214] Zündel's lawyer, Doug Christie, tried to undermine Vrba (and three other survivors) by requesting ever more detailed descriptions, then presenting any discrepancy as significant. According to Lawrence Douglas, when Vrba said he had watched bodies burn in a pit, Christie asked how deep the pit had been; when Vrba described an SS officer climbing onto the roof of a gas chamber, Christie asked about the height and angle.[215] When Vrba told Christie he was not willing to discuss his book unless the jury had read it, the judge reminded him not to give orders.[216]

Christie argued that Vrba's knowledge of the gas chambers was secondhand.[217] According to Vrba's deposition for Adolf Eichmann's trial in 1961,[203] he obtained information about the gas chambers from Sonderkommando Filip Müller and others who worked there, something that Müller confirmed in 1979.[127] Christie asked whether he had seen anyone gassed. Vrba replied that he had watched people being taken into the buildings and had seen SS officers throw in gas canisters after them: "Therefore, I concluded it was not a kitchen or a bakery, but it was a gas chamber. It is possible they are still there or that there is a tunnel and they are now in China. Otherwise, they were gassed."[218] The trial ended with Zündel's conviction for knowingly publishing false material about the Holocaust.[219][214] In R v Zundel (1992), the Supreme Court of Canada upheld Zundel's appeal on free-speech grounds.[220]

Meeting with George Klein

In 1987 the Swedish–Hungarian biochemist George Klein travelled to Vancouver to thank Vrba; he had read the Vrba–Wetzler report in 1944 as a teenager in Budapest and escaped because of it. He wrote about the meeting in an essay, "The Ultimate Fear of the Traveler Returning from Hell", for his book Pietà (1992).[221] The traveller's ultimate fear, English scholar Elana Gomel wrote in 2003, was that he had seen Hell but would not be believed; in this case, the traveller knows something that "cannot be put into any human language".[222]

Despite the significant influence Vrba had on Klein's life, Klein's first sight of Vrba was the latter's interview in Shoah in 1985. He disagreed with Vrba's allegations about Kastner; Klein had seen Kastner at work in the Jewish Council offices in Budapest, where Klein had worked as a secretary, and he viewed Kastner as a hero. He told Vrba how he had tried himself, in the spring of 1944, to convince others in Budapest of the Vrba–Wetzler report's veracity, but no one had believed him, which inclined him to the view that Vrba was wrong to argue that the Jews would have acted had they known about the death camps. Vrba said that Klein's experience illustrated his point: distributing the report via informal channels had lent it no authority.[223]

Klein asked Vrba how he could function in the pleasant, provincial atmosphere of the University of British Columbia, where no one had any concept of what he had been through. Vrba told him about a colleague who had seen him in Lanzmann's film and asked whether what the film had discussed was true. Vrba replied: "I do not know. I was only an actor reciting my lines." "How strange," the colleague replied. "I didn't know that you were an actor. Why did they say that film was made without any actors?"[224] Klein wrote:

Only now did I understand that this was the same man who lay quiet and motionless for three days in the hollow pile of lumber while Auschwitz was on maximum alert, only a few yards from the armed SS men and their dogs combing the area so thoroughly. If he could do that, then he certainly could also don the mask of a professor and manage everyday conversation with his colleagues in Vancouver, Canada, that paradise land that is never fully appreciated by its own citizens, a people without the slightest notion of the planet Auschwitz.[225]

Death

Vrba's fellow escapee, Alfréd Wetzler, died in Bratislava, Slovakia, on 8 February 1988. Wetzler was the author of Escape From Hell: The True Story of the Auschwitz Protocol (2007), first published as Čo Dante nevidel (lit. "What Dante didn't see", 1963) under the pseudonym Jozef Lánik.

Vrba died of cancer, aged 81, on 27 March 2006 in hospital in Vancouver.[209] He was survived by his first wife, Gerta Vrbová; his second wife, Robin Vrba; his daughter, Zuza Vrbová Jackson; and his grandchildren, Hannah and Jan.[188][199][209] He was pre-deceased by his elder daughter, Dr. Helena Vrbová, who died in 1982 in Papua New Guinea during a malaria research project.[193] Robin Vrba made a gift of Vrba's papers to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in New York.[226]

Reception

Documentaries, books, annual walk

Several documentaries have told Vrba's story, including Genocide (1973), directed by Michael Darlow for ITV in the UK; Auschwitz and the Allies (1982), directed by Rex Bloomstein and Martin Gilbert for the BBC; and Claude Lanzmann's Shoah. Vrba was also featured in Witness to Auschwitz (1990), directed by Robin Taylor for the CBC in Canada; Auschwitz: The Great Escape (2007) for the UK's Channel Five; and Escape From Auschwitz (2008) for PBS in the United States. George Klein, the Hungarian-Swedish biologist who read the Vrba–Wetzler report in Budapest as a teenager, and who escaped rather than board a train to Auschwitz, wrote about Vrba in his book Pietà (MIT Press, 1992).[221]

In 2001 Mary Robinson, then United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Vaclav Havel, then President of the Czech Republic, established the "Rudy Vrba Award" for films in the "right to know" category about unknown heroes.[199][227] In 2014 the Vrba–Weztler Memorial began organizing an annual 130-km, five-day walk from the "Mexico" section of Auschwitz, where the men hid for three days, to Žilina, Slovakia, following the route they took.[228] In January 2020 a PBS film Secrets of the Dead: Bombing Auschwitz presented a reconstruction of Vrba's escape, with David Moorst as Vrba and Michael Fox as Wetzler.[229]

In 2022, Vrba was the subject of The Escape Artist[230][231] a biography by Jonathan Freedland detailing Vrba's life, escape and its aftermath, and his life after the war.

Scholarship

Vrba's place in Holocaust historiography was the focus of Ruth Linn's Escaping Auschwitz: A Culture of Forgetting (Cornell University Press, 2004). The Rosenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies at the City University of New York held an academic conference in April 2011 to discuss the Vrba–Wetzler and other Auschwitz reports, resulting in a book, The Auschwitz Reports and the Holocaust in Hungary (Columbia University Press, 2011), edited by Randolph L. Braham and William vanden Heuvel.[226] In 2014 the British historian Michael Fleming reappraised the impact of the Vrba–Wetzler report in Auschwitz, the Allies and Censorship of the Holocaust (Cambridge University Press, 2014).[232]

Awards

The University of Haifa awarded Vrba an honorary doctorate in 1998 at the instigation of Ruth Linn,[207] with support from Yehuda Bauer.[233]

For having fought during the Slovak National Uprising, Vrba was awarded the Czechoslovak Medal for Bravery, the Order of Slovak National Insurrection (Class 2), and the Medal of Honor of Czechoslovak Partisans.[234]

In 2007 he received the Order of the White Double Cross, 1st class, from the Slovak government.[235]

British historian Martin Gilbert supported an unsuccessful campaign in 1992 to have Vrba awarded the Order of Canada. The campaign was supported by Irwin Cotler, the former Attorney General of Canada, who at the time was a professor of law at McGill University.[e] Similarly, Bauer proposed unsuccessfully that Vrba be awarded an honorary doctorate from the Hebrew University.[233]

Disputes

About Hungarian Jews

Vrba stated that warning the Hungarian community was one of the motives for his escape. His statement to that effect was first published on 27 February 1961, in the first installment of a five-article series about Vrba by a journalist, Alan Bestic, for the Daily Herald in England. In the second installment the next day, Vrba described having overheard the SS say they were looking forward to Hungarian salami, a reference to the provisions Hungarian Jews were likely to carry.[237] Vrba said that in January 1944 a kapo had told him the Germans were building a new railway line to bring the Jews of Hungary directly into Auschwitz II.[238]

The Czech historian Miroslav Kárný noted that there is no mention of Hungarian Jews in the Vrba–Wetzler report.[239] Randolph L. Braham also questioned Vrba's later recollections.[240] The Vrba–Wetzler report said only that Greek Jews were expected: "When we left on April 7, 1944 we heard that large convoys of Greek Jews were expected."[241] It also said: "Work is now proceeding on a still larger compound which is to be added later on to the already existing camp. The purpose of this extensive planning is not known to us."[242]

In 1946, Dr. Oskar Neumann, head of the Jewish Council in Slovakia, whose interviews with Vrba and Wetzler in April 1944 helped to form the Vrba–Wetzler report, wrote in his memoir Im Schatten des Todes (published in 1956)[243] that the men had indeed mentioned Hungarian salami to him during the interviews: "These chaps did also report that recently an enormous construction activity had been initiated in the camp and very recently the SS often spoke about looking forward to the arrival of Hungarian salami."[f] Vrba wrote that the original Slovak version of the Vrba–Wetzler report, some of which he wrote by hand, may have referred to the imminent Hungarian deportations. That version of the report did not survive; it was the German translation that was copied. Vrba had argued strongly for the inclusion of the Hungarian deportations, he wrote, but he recalled Oskar Krasniansky, who translated the report into German, saying that only actual deaths should be recorded, not speculation. He could not recall which argument prevailed.[247] Alfred Wetzler's memoirs, Escape from Hell (2007), also say that he and Vrba told the Slovak Jewish Council about the new ramp, the expectation of half a million Hungarian Jews, and the mention of Hungarian salami.[248]

Attorney-General v. Gruenwald

It was a source of distress to Vrba for the rest of his life that the Vrba–Wetzler report had not been distributed widely until June–July 1944, weeks after his escape in April. Between 15 May and 7 July 1944, 437,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz, and most murdered on arrival.[249] In his view, the deportees boarded the trains in the belief they were being sent to some kind of Jewish reservation.[250]

Arguing that the deportees would have fought or run had they known the truth, or at least that panic would have slowed the transports, Vrba alleged that Rezső Kasztner of the Budapest Aid and Rescue Committee (who had a copy of the Vrba–Wetzler report by 3 May 1944 at the latest) had held back the report to avoid jeopardizing complex, and mostly futile, negotiations with Adolf Eichmann and other SS officers to exchange Jews for money and goods.[251] In taking part in these negotiations, Vrba argued, the SS was simply placating the Jewish leadership to avoid rebellion within the community.[252]

In I Cannot Forgive (1963), Vrba drew attention to the 1954 trial in Jerusalem of Malchiel Gruenwald, a Hungarian Jew living in Israel.[253] In 1952 Gruenwald accused Rezső "Rudolf" Kasztner, who had become a civil servant in Israel, of having collaborated with the SS so that he could escape from Hungary with a select few, including his family.[254] Kastner had bribed the SS to allow over 1,600 Jews to leave Hungary for Switzerland on the Kastner train in June 1944, and he had testified on behalf of leading SS officers, including Kurt Becher, at the Nuremberg trials.[g]

Vrba agreed with Gruenwald's criticism of Kastner. In Attorney-General of the Government of Israel v. Malchiel Gruenwald, the Israeli government sued Gruenwald for libel on Kastner's behalf. In June 1955, Judge Benjamin Halevi decided mostly in Gruenwald's favour, ruling that Kastner had "sold his soul to the devil".[256] "Masses of ghetto Jews boarded the deportation trains in total obedience," Halevi wrote, "ignorant of the real destination and trusting the false declaration that they were being transferred to work camps in Hungary." The Kastner train had been a pay-off, the judge said, and the protection of certain Jews had been "an inseparable part of the maneuvers in the 'psychological war' to destroy the Jews". Kastner was assassinated in Tel Aviv in March 1957; the verdict was partly overturned by the Supreme Court of Israel in 1958.[257]

Criticism of Jewish Councils

In addition to blaming Kastner and the Hungarian Aid and Rescue Committee for having failed to distribute the Vrba–Wetzler report, Vrba criticized the Slovak Jewish Council for having failed to resist the deportation of Jews from Slovakia in 1942. When he was deported from Slovakia to the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland in June that year, the Jewish Council had known, he alleged, that Jews were being murdered in Poland, but they did nothing to warn the community and even assisted by drawing up lists of names.[258] He referred to Jewish leaders in Slovakia and Hungary as "quislings" who were essential to the smooth running of the deportations: "The creation of Quislings, voluntary or otherwise, was, in fact, an important feature of Nazi policy" in every occupied country, in his view.[259]

The Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer argued that while the Council knew that being sent to Poland meant severe danger for Jews, at that stage they did not know about the Final Solution[258] It is true, Bauer wrote, that Jewish Council members, under Karol Hochberg, head of the council's "department for special tasks", had worked with the SS, offering secretarial and technical help to draw up lists of Jews to be deported (lists supplied by the Slovak government). But other members of the Jewish Council warned Jews to flee and later formed a resistance, the Working Group, which in December 1943 took over the Jewish Council, with Oskar Neumann (the lawyer who helped to organize the Vrba–Wetzler report) as its leader.[260] Vrba did not accept Bauer's distinctions.[259]

Responses

Vrba's position that the Jewish leadership in Hungary and Slovakia betrayed their communities was supported by the Anglo-Canadian historian John S. Conway, a colleague of his at the University of British Columbia, who from 1979 wrote a series of papers in defence of Vrba's views.[261] In 1996 Vrba repeated the allegations in an article, "Die mißachtete Warnung: Betrachtungen über den Auschwitz-Bericht von 1944" ("The warning that was ignored: Considerations of an Auschwitz report from 1944") in Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte,[262] to which the Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer responded in 1997 in the same journal.[263] Bauer responded to Conway in 2006.[264]

In Bauer's opinion, Vrba's "wild attacks on Kastner and on the Slovak underground are all a-historical and simply wrong from the start", although he acknowledged that many survivors share Vrba's view.[233] By the time the Vrba–Wetzler report had been prepared, Bauer argued, it was too late for anything to alter the Nazis' deportation plans.[265] Bauer expressed the view that Hungarian Jews knew about the mass murder in Poland even if they did not know the particulars; and if they had seen the Vrba–Wetzler report, they would have been forced onto the trains anyway.[266] In response, Vrba alleged that Bauer was one of the Israeli historians who, in defence of the Israeli establishment, had downplayed Vrba's place in Holocaust historiography.[267]

The British historian Michael Fleming argued in 2014 against the view that Hungarian Jews had sufficient access to information. After the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944, the British government's Political Warfare Executive (PWE) directed the BBC's Hungarian Service to run Allied warnings to the Hungarian government that "racial persecution will be regarded as a war crime".[268] However, on 13 April, the PWE decided against broadcasting warnings directly to Hungarian Jews on the grounds that it would "cause unnecessary alarm" and that "they must in any case be only too well-informed of the measures that may be taken against them".[269][h] Fleming writes that this was a mistake: the Germans had tricked the Jewish community into thinking they were being sent to Poland to work.[269] The first mention of extermination camps in the PWE's directives to the BBC's Hungarian Service came on 8 June 1944.[272]

Randolph L. Braham, a specialist in the Holocaust in Hungary, agreed that Hungarian Jewish leaders did not keep the Jewish communities informed or take "any meaningful precautionary measures" to deal with the consequences of a German invasion. He called this "one of the great tragedies of the era".[i] Nevertheless, it remains true, he argued, that by the time the Vrba–Wetzler report was available, the Jews of Hungary were in a helpless state: "marked, hermetically isolated, and expropriated". In northeastern Hungary and Carpatho-Ruthenia, the women, children and elderly were living in crowded ghettos, in unsanitary conditions and with little food, while the younger men were in military service in Serbia and Ukraine. There was nothing they could have done to resist, he wrote, even if they had known about the report.[274]

Vrba was criticized in 2001 in a collection of articles in Hebrew, Leadership under Duress: The Working Group in Slovakia, 1942–1944, by a group of Israeli activists and historians, including Bauer, with ties to the Slovak community. The introduction, written by a survivor, refers to the "bunch of mockers, pseudo-historians and historians" who argue that the Bratislava Working Group collaborated with the SS, a "baseless" allegation that ignores the constraints under which the Jews in Slovakia and Hungary were living. Vrba (referred to as "Peter Vrba") is described as "the head of these mockers", although the introduction makes clear that his heroism is "beyond doubt". It concludes: "We, Czechoslovak descendants, who personally experienced [the war] cannot remain silent in face of these false accusations."[275]

Vrba's place in Holocaust historiography

In Vrba's view, Israeli historians tried to erase his name from Holocaust historiography because of his views about Kastner and the Hungarian and Slovak Jewish Councils, some of whom went on to hold prominent positions in Israel. When Ruth Linn first tried to visit Vrba in British Columbia, he practically "chased her out of his office", according to Uri Dromi in Haaretz, saying he had no interest in "your state of the Judenrats and Kastners".[207]

Linn wrote in her book about Vrba, Escaping Auschwitz: A Culture of Forgetting (2004), that Vrba's and Wetzler's names had been omitted from Hebrew textbooks or their contribution minimized: standard histories refer to the escape by "two young Slovak Jews", "two chaps", and "two young men", and represent them as emissaries of the Polish underground in Auschwitz. Bauer also attacked Vrba, calling him 'bitter Auschwitz survivor’, ‘embittered and furious’, and ‘(his) despair and bitterness are overdone’. Bauer didn't admit until 1997 that Vrba was a trustworthy eyewitness. [276] Dr. Oskar Neumann of the Slovak Jewish Council referred to them in his memoir as "these chaps"; Oskar Krasniansky, who translated the Vrba–Wetzler report into German, mentioned them only as "two young people" in his deposition for the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961. There was also a tendency to refer to the Vrba–Wetzler report as the Auschwitz Protocols, which is a combination of the Vrba–Wetzler and two other reports. The 1990 edition of the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, published by Yad Vashem in Israel, did name Vrba and Wetzler, but in the 2001 edition they are "two Jewish prisoners".[277]

Vrba's memoir was not translated into Hebrew until 1998, 35 years after its publication in English. As of that year, there was no English or Hebrew version of the Vrba–Wetzler report at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, an issue the museum attributed to lack of funding. There was a Hungarian translation, but it did not note the names of its authors and, Linn wrote, could be found only in a file that dealt with Rudolf Kastner.[278] Linn herself, born and raised in Israel and schooled at the prestigious Hebrew Reali School, first learned about Vrba when she watched Claude Lanzmann's film Shoah (1985).[279] In 1998 she polled 594 students at the University of Haifa, either third-year undergraduates or first-year graduate students; 98 percent said that no one had ever escaped from Auschwitz, and the remainder did not know the escapees' names.[280] This failure to acknowledge Vrba has played into the hands of Holocaust deniers, who have tried to undermine his testimony about the gas chambers.[281][207]

In 1999, the Verba–Wetzler report was published in Hebrew.[282]

In 2005, Uri Dromi of the Israel Democracy Institute responded that there were at least four Israeli books on the Holocaust that mention Vrba, and that Wetzler's testimony is recounted at length in Livia Rothkirchen's Hurban yahadut Slovakia ("The Destruction of Slovak Jewry"), published by Yad Vashem in 1961.[207]

In 2005, Vrba memoirs were published in Hebrew by Yad Vashem.[282]

Selected works

Holocaust

- (1998). "Science and the Holocaust" Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Focus, University of Haifa (edited version of Vrba's speech when he received his honorary doctorate).

- (1997). "The Preparations for the Holocaust In Hungary: An Eyewitness Account", in Randolph L. Braham, Attila Pok (eds.). The Holocaust in Hungary. Fifty years later. New York: Columbia University Press, 227–285.

- (1998). "The Preparations for the Holocaust In Hungary: An Eyewitness Account", in Randolph L. Braham, Attila Pok (eds.). The Holocaust in Hungary. Fifty years later. New York: Columbia University Press, 227–285.

- (1996). "Die mißachtete Warnung. Betrachtungen über den Auschwitz-Bericht von 1944". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 44(1), 1–24. JSTOR 30195502

- (1992). "Personal Memories of Actions of SS-Doctors of Medicine in Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II (Birkenau)", in Charles G. Roland et al. (eds.). Medical Science without Compassion, Past and Present. Hamburg: Stiftung für Sozialgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. OCLC 34310080

- (1989). "The Role of Holocaust in German Economy and Military Strategy During 1941–1945", Appendix VII in I Escaped from Auschwitz, 431–440.

- (1966). "Footnote to the Auschwitz Report", Jewish Currents, 20(3), 27.

- (1963) with Alan Bestic. I Cannot Forgive. London: Sidgwick and Jackson.

- (1964) with Alan Bestic. Factory of Death. London: Transworld Publishers.

- (1989) with Alan Bestic. 44070: The Conspiracy of the Twentieth Century. Bellingham, WA: Star & Cross Publishing House.

- (2002). I Escaped from Auschwitz. London: Robson Books.

Academic research

- (1975) with E. Alpert; K. J. Isselbacher. "Carcinoembryonic antigen: evidence for multiple antigenic determinants and isoantigens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 72(11), November 1975, 4602–4606. PMID 53843 PMC 388771

- (1974) with A. Winter; L. N. Epps. "Assimilation of glucose carbon in vivo by salivary gland and tumor". American Journal of Physiology, 226(6), June 1974, 1424–1427.

- (1972) with A. Winter. "Movement of (U- 14 C)glucose carbon into and subsequent release from lipids and high-molecular-weight constituents of rat brain, liver, and heart in vivo". Canadian Journal of Biochemistry, 50(1), January 1972, 91–105. PMID 5059675

- (1970) with Wendy Cannon. "Molecular weights and metabolism of rat brain proteins". Biochemical Journal, 116(4), February 1970, 745–753. PMID 5435499 PMC 1185420

- (1968) with Wendy Cannon. "Gel filtration of [U-14C]glucose-labelled high-speed supernatants of rat brains". Journal of Biochemistry, 109(3), September 1968, 30P. PMID 5685853 PMC 1186863

- (1967). "Assimilation of glucose carbon in subcellular rat brain particles in vivo and the problems of axoplasmic flow". Journal of Biochemistry, 105(3), December 1967, 927–936. PMID 16742567 PMC 1198409

- (1966). "Effects of insulin-induced hypoglycaemia on the fate of glucose carbon atoms in the mouse". Journal of Biochemistry, 99(2), May 1966, 367–380. PMID 5944244 PMC 265005

- (1964). "Utilization of glucose carbon in vivo in the mouse". Nature, 202, 18 April 1964, 247–249. PMID 14167775

- (1963) with H. S. Bachelard; J. Krawcynski. "Interrelationship between glucose utilization of brain and heart". Nature, 197, 2 March 1963, 869–870. PMID 13998012

- (1962) with H. S. Bachelard, et al. "Effect of reserpine on the heart". The Lancet, 2(7269), 22 December 1962, 1330–1331. PMID 13965902

- (1962) with M. K. Gaitonde; D. Richter. "The conversion of the glucose carbon into protein in the brain and other organs of the rat". Journal of Neurochemistry, 9(5), September 1962, 465–475. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1962.tb04199.x PMID 13998013

- (1962). "Glucose metabolism in rat brain in vivo". Nature, 195 (4842), August 1962, 663–665. doi:10.1038/195663a0 PMID 13926895