Cyril and Methodius

Cyril and Methodius | |

|---|---|

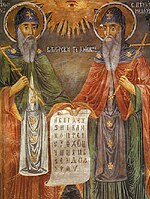

"Saints Cyril and Methodius holding the Cyrillic alphabet," a mural by Bulgarian iconographer Z. Zograf, 1848, Troyan Monastery | |

| Bishops and Confessors; Equals to the Apostles; Patrons of Europe; Apostles to the Slavs | |

| Born | 826 or 827 and 815 Thessalonica, Byzantine Empire (present-day Greece) |

| Died | 14 February 869 and 6 April 885 Rome and Velehrad, Great Moravia |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Catholic Church Anglican Communion[1] Lutheranism[2] |

| Feast | 11 and 24 May[3] (Eastern Orthodox Church) 14 February (present Roman Catholic calendar); 5 July (Roman Catholic calendar 1880–1886); 7 July (Roman Catholic calendar 1887–1969) 5 July (Roman Catholic and Lutheran Czech Republic and Slovakia) |

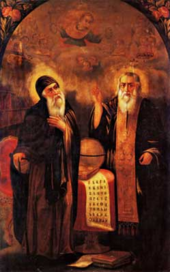

| Attributes | Brothers depicted together; Eastern bishops holding up a church; Eastern bishops holding an icon of the Last Judgment.[4] Often, Cyril is depicted wearing a monastic habit and Methodius vested as a bishop with omophorion. |

| Patronage | Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Transnistria, Serbia, Archdiocese of Ljubljana, Europe,[4] Slovak Eparchy of Toronto, Eparchy of Košice[5] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Cyril (Greek: Κύριλλος, romanized: Kýrillos; born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (Μεθόδιος, Methódios; born Michael, 815–885) were brothers, Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".[6]

They are credited with devising the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet used to transcribe Old Church Slavonic.[7] After their deaths, their pupils continued their missionary work among other Slavs. Both brothers are venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as saints with the title of "equal-to-apostles". In 1880, Pope Leo XIII introduced their feast into the calendar of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. In 1980, the first Slav pope, Pope John Paul II declared them co-patron saints of Europe, together with Benedict of Nursia.[8]

Early career

Early life

The two brothers were born in Thessalonica, at that time in the Byzantine province of the same name (today in Greece) – Cyril in 827–828, and Methodius in 815–820. According to the Vita Cyrilli ("The Life of Cyril"), Cyril was reputedly the youngest of seven brothers; he was born Constantine,[9] but was given the name Cyril upon becoming a monk in Rome shortly before his death.[10][11][12] Methodius was born Michael and was given the name Methodius upon becoming a monk in Polychron Monastery at Mysian Olympus (present-day Uludağ in northwest Turkey).[13] Their father was Leo, a droungarios of the Byzantine theme of Thessalonica, and their mother's name was Maria.

The exact ethnic origins of the brothers are unknown; there is controversy as to whether Cyril and Methodius were of Slavic[14] or Greek[15] origin, or both.[16] The two brothers lost their father when Cyril was fourteen, and the powerful minister Theoktistos, who was logothetes tou dromou, one of the chief ministers of the Empire, became their protector. He was also responsible, along with the regent Bardas, for initiating a far-reaching educational program within the Empire which culminated in the establishment of the University of Magnaura, where Cyril was to teach. Cyril was ordained as priest some time after his education, while his brother Methodius remained a deacon until 867/868.[17]

Mission to the Khazars

About the year 860, Byzantine Emperor Michael III and the Patriarch of Constantinople Photius (a professor of Cyril's at the university and his guiding light in earlier years), sent Cyril on a missionary expedition to the Khazars who had requested a scholar be sent to them who could converse with both Jews and Saracens.[18] It has been claimed that Methodius accompanied Cyril on the mission to the Khazars, but this may be a later invention. The account of his life presented in the Latin "Legenda" claims that he learned the Khazar language while in Chersonesos, in Taurica (today Crimea).

After his return to Constantinople, Cyril assumed the role of professor of philosophy at the university. His brother had by this time become a significant figure in Byzantine political and administrative affairs, and an abbot of his monastery.

Mission to the Slavs

Great Moravia

In 862, the brothers began the work which would give them their historical importance. That year Prince Rastislav of Great Moravia requested that Emperor Michael III and the Patriarch Photius send missionaries to evangelize his Slavic subjects. His motives in doing so were probably more political than religious. Rastislav had become king with the support of the Frankish ruler Louis the German, though he subsequently sought to assert his independence from the Franks. That Cyril and Methodius might have been the first to bring Christianity to Moravia is a common misconception; Rastislav's letter to Michael III states clearly that his people "had already rejected paganism and adhere to the Christian law."[19] Rastislav is said to have expelled missionaries of the Roman Church and instead turned to Constantinople for ecclesiastical assistance and, presumably, a degree of political support.[20] The Emperor quickly chose to send Cyril, accompanied by his brother Methodius.[21] The request provided a convenient opportunity to expand Byzantine influence. Their first work seems to have been the training of assistants. In 863, they began the task of translating the Gospels and essential liturgical books into what is now known as Old Church Slavonic,[22] and travelled to Great Moravia to promote it.[23] This endeavour was amply rewarded. However, they came into conflict with German ecclesiastics, who opposed their efforts to create a specifically Slavic liturgy.

For the purpose of this mission, they devised the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet to be used for Slavonic manuscripts. The Glagolitic alphabet was suited to match the specific features of the Slavic language. Its descendant script, the Cyrillic, is still used by many languages today.[20]

The brothers wrote the first Slavic Civil Code, which was used in Great Moravia. The language derived from Old Church Slavonic, known as Church Slavonic, is still used in the liturgy by several Orthodox Churches, and also in some Eastern Catholic churches.

Exactly how much the brothers translated is impossible to say for certain. The New Testament and the Psalms seem to have been the first, followed by other lessons from the Old Testament.[citation needed] The "Translatio" speaks only of a version of the Gospels by Cyril, and the "Vita Methodii" only of the "evangelium Slovenicum", though other liturgical selections may also have been translated.

Nor is it known for sure which liturgy, whether of Rome or of Constantinople, they took as a source. They may well have used the Roman alphabet, as hinted by liturgical fragments adhering closely to the Latin type. This view is confirmed by the "Prague Fragments" and by certain Old Glagolitic liturgical fragments brought from Jerusalem to Kyiv and discovered there by Izmail Sreznevsky—probably the oldest document in the Slavonic tongue; examples of where they resemble the Latin type include the words "Mass," "Preface," and the name of one Felicitas. Regardless, the circumstances were such that the brothers could have hoped for no lasting success without having had authorization from Rome.

Journey to Rome

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2019) |

The mission of Constantine and Methodius had great success among Slavs in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin or Greek. In Great Moravia, Constantine and Methodius also encountered missionaries from East Francia. They would have represented the western, or Latin, branch of the Church, more particularly epitomizing the Carolingian Empire as founded by Charlemagne, and intent on linguistic and cultural uniformity. They insisted on the use of the Latin liturgy, and they regarded Moravia and the Slavic peoples as part of their rightful mission field.

When friction developed, the brothers, unwilling to be a cause of dissension among Christians, decided to travel to Rome to see the Pope, and seek a solution that would avoid quarrelling between missionaries in the field. In 867, Pope Nicholas I (858-867) invited the brothers to Rome. Their evangelizing mission in Moravia had by this time become the focus of a dispute with Archbishop Adalwin of Salzburg (859–873) and Bishop Ermanrich of Passau (866-874). They claimed ecclesiastical control of the same territory and wished to see it use the Latin liturgy exclusively.

With them they brought the relics of Saint Clement and a retinue of disciples. They passed through Pannonia (the Balaton Principality), where they were well received by Prince Koceľ. This activity in Pannonia made a continuation of conflicts inevitable with the German episcopate, and especially with the bishop of Salzburg, whose prerogative Pannonia had been for seventy-five years. As early as 865, Bishop Adalwin was found to exercise Episcopal rights there. The administration under him was in the hands of the archpriest Riehbald. He was obliged to retire to Salzburg, though his superior was instinctively disinclined to abandon his claim.

The brothers sought support from Rome, and arrived there in 868, where they were warmly received. This was partly due to their bringing with them the relics of Saint Clement; rivalry with Constantinople over the territory of the Slavs would have inclined Rome to value the brothers and their influence.[20]

The brothers were praised for their learning and cultivated for their influence in Constantinople. Anastasius Bibliothecarius would later call Cyril "a man of apostolic life" and "a man of great wisdom".[24] Their project in Moravia found support from the new Pope Adrian II (867-872), who formally authorized the use of the new Slavic liturgy.

Subsequently, Methodius was ordained as priest by the pope himself, and five Slavic disciples were ordained as priests (Saint Gorazd, Saint Clement of Ohrid and Saint Naum) and as deacons (Saint Angelar and Saint Sava) by the prominent bishops Formosus and Gauderic.[25] Since the 10th century Cyril and Methodius along with these five disciples are collectively venerated by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church as the "Seven Saints".[26][27] The newly made priests officiated in their own language at the altars of some of the principal churches.

Feeling his end approaching, Cyril became a Basilian monk and was given the name Cyril.[28] He died in Rome fifty days later (14 February 869). There is some question whether he had been made a bishop, as is asserted in the Translatio (ix.). Upon Cyril´s death Methodius was given the title of Archbishop of Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia) with jurisdiction over all of Moravia and Pannonia, and authority to use the Slavonic Liturgy.[29] The statement of the "Vita" that Methodius was made bishop in 870 and not raised to the dignity of an archbishop until 873 is contradicted by the brief of Pope John VIII, written in June 879, according to which Adrian consecrated him archbishop; John includes in his jurisdiction not only Great Moravia and Pannonia, but Serbia as well.

Methodius alone

Methodius now continued the work among the Slavs alone; not at first in Great Moravia, but in Pannonia (in the Balaton Principality). Political circumstances in Greater Moravia were insecure. Rastislav had been taken captive by his nephew Svatopluk in 870, then delivered over to Carloman of Bavaria, and condemned in a diet held at Regensburg at the end of 870. Meanwhile, the East Frankish rulers and their bishops decided to try and depose Methodius. The archiepiscopal claims of Methodius were considered so threatening to the rights of Salzburg that he was captured and forced to answer to East Frankish bishops: Adalwin of Salzburg, Ermanrich of Passau, and Anno of Freising. After heated discussion, they declared the intruder deposed, and ordered him to be sent to Germany. There he was kept prisoner in a monastery for two and a half years.[30]

Notwithstanding strong representations of the Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum, written in 871 to influence the pope, though not conceding this purpose, Rome declared emphatically for Methodius. He sent a bishop, Paul of Ancona, to reinstate him and punish his enemies, after which both parties were ordered to appear in Rome with the legate. Thus in 873, new Pope John VIII (872-882) secured the release of Methodius, but instructed him to stop using the Slavonic Liturgy.[31]

Methodius' final years

The papal will prevailed, and Methodius secured his freedom and his archiepiscopal authority over both Great Moravia and Pannonia, albeit without the use of Slavonic for Mass in the Catholic Church. His authority in Pannonia was restricted after Koceľ's death, when the principality was administered by German nobles. However, Svatopluk now ruled practically independently in Great Moravia, and he expelled the German clergy. It seems this secured an undisturbed field of operation for Methodius, and the Vita (x.) depicts the next few years (873–879) as a time of fruitful progress. Methodius seems to have disregarded, wholly or in part, the prohibition of the Slavonic liturgy. When Frankish clerics again ventured into the country, revealing a permissive Svatopluk at odds with his punctilious archbishop, this was made a cause of complaint against him at Rome, coupled with charges regarding the Filioque.

In 878, Methodius was summoned to Rome on charges of heresy and using Slavonic. This time Pope John was convinced by the arguments that Methodius made in his defence and sent him back cleared of all charges, and with permission to use Slavonic. The Carolingian bishop who succeeded him, Wiching, a Swabian, suppressed the Slavonic Liturgy and forced the followers of Methodius into exile. Many found refuge with Knyaz Boris the Baptizer in Bulgaria, under whom they reorganized a Slavic-speaking Church. Meanwhile, Pope John's successors adopted a Latin-only policy which lasted for centuries.

Methodius vindicated his orthodoxy and promised to obey with regard to the liturgy. He could the more easily defend his omission of Filioque from the creed as this also pertained in Rome at the time. Though Filioque could, by the 6th century, be heard in some Latin-speaking churches in the west, it was not to be until 1014 that Rome followed suit (see Nicene Creed). Methodius' critics were mollified by Methodius having to accept the appointment of Wiching as his coadjutor. When relations between the two factions again became strained, John VIII steadfastly supported Methodius. After his death (December 882) it was the archbishop himself whose position looked insecure. His need for political support, visiting the Eastern emperor, inclined Goetz to accept the account in the Vita (xiii.).

Methodius died on 6 April 885[32] and his body was buried in the main cathedral church of Great Moravia. It still remains an open question which city was capital of Great Moravia. As a result the location of Methodius' body remains uncertain.[33]

Upon Methodius' death an animosity erupted into open conflict. Amongst the disciples of Cyril and Methodius, Clement of Ohrid headed the struggle against the German clergy in Great Moravia along with Gorazd upon the death of Methodius in 885. Gorazd, whom Methodius had designated as his successor, was not recognised by Pope Stephen V. This pope now also forbade the Slavic liturgy[34] and placed as Methodius' successor the infamous Wiching who promptly sent disciples of Cyril and Methodius into exile from Great Moravia.

After spending some time in jail, Clement was expelled from Great Moravia, and in 885 or 886 reached the borders of the First Bulgarian Empire together with Naum, Angelar, and possibly also Gorazd (other sources suggest Gorazd had already died by that time). Angelar soon died after an arrival, but Clement and Naum were afterwards sent to the Bulgarian capital of Pliska, where they were commissioned by Boris I to instruct the future clergy of the state in the Slavonic language. Eventually they were commissioned to establish two theological schools - the Ohrid Literary School in Ohrid and the Preslav Literary School in Preslav. The Preslav Literary School had been originally established in Pliska, but was moved to Preslav in 893.

Invention of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets

The Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets are the oldest known Slavic alphabets, and were created by the two brothers and/or their students, to translate the Gospels and liturgical books[22] into the Slavic languages.[35]

The early Glagolitic alphabet was used in Great Moravia between 863 (the arrival of Cyril and Methodius) and 885 (the expulsion of their students) for government and religious documents and books, and at the Great Moravian Academy (Veľkomoravské učilište) founded by Cyril, where followers of Cyril and Methodius were educated, by Methodius himself among others. The alphabet has been traditionally attributed to Cyril. That seems confirmed explicitly by the papal letter Industriae tuae (880) approving the use of Old Church Slavonic, which says that the alphabet was "invented by Constantine the Philosopher". "Invention" need not exclude the brothers having possibly made use of earlier letterforms. Before that time the Slavic languages had no distinct script of their own.

The early Cyrillic alphabet was developed by the disciples of Saints Cyril and Methodius at the Preslav Literary School at the end of the 9th century as a simplification of the Glagolitic alphabet which more closely resembled the Greek alphabet. The Cyrillic script was devised from the Greek alphabet and Glagolitic alphabet.[36] Cyrillic gradually replaced Glagolitic as the alphabet of the Old Church Slavonic language, which became the official language of the First Bulgarian Empire and later spread to the Eastern Slav lands of Kievan Rus'. Cyrillic eventually spread throughout most of the Slavic world to become the standard alphabet in the Eastern Orthodox Slavic countries. In this way the work of Cyril and Methodius and their disciples enabled the spread of Christianity throughout Eastern Europe.

After the adoption of Christianity in 865, religious ceremonies in Bulgaria were conducted in Greek by clergy sent from the Byzantine Empire. Fearing growing Byzantine influence and weakening of the state, Boris viewed the adoption of the Old Slavonic language as a way to preserve the political independence and stability of Bulgaria, so he established two literary schools (academies), in Pliska and Ohrid, where theology was to be taught in the Slavonic language. While Naum of Preslav stayed in Pliska working on the foundation of the Pliska Literary School which was moved to Preslav in 893, Clement was commissioned by Boris I to organise the teaching of theology to future clergymen in Old Church Slavonic at the Ohrid Literary School. Over seven years (886-893) Clement taught some 3,500 students in the Slavonic language and the Glagolitic alphabet.

Commemoration

Saints Cyril and Methodius' Day

Compared to nowadays, the process leading to canonization was less involved in the decades following Cyril's death. Cyril was regarded by his disciples as a saint soon after his death. His following spread among the nations he evangelized, and subsequently to the wider Christian Church. With his brother Methodius, he was famous as a man of holiness. From the crowds lining the Roman streets during his funeral procession, there were calls for Cyril to be accorded saintly status. The brothers' first appearance in a papal document is in Grande Munus of Leo XIII in 1880. They are known as the "Apostles of the Slavs", and are still highly regarded by both Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians. Their feast day is currently celebrated on 14 February in the Roman Catholic Church (to coincide with the date of St Cyril's death); on 11 May in the Eastern Orthodox Church (though for Eastern Orthodox Churches which use the Julian Calendar this is 24 May according to the Gregorian calendar); and on 7 July according to the old sanctoral calendar before the revisions of the Second Vatican Council. The celebration also commemorates the introduction of literacy and the preaching of the gospels in the Slavonic language by the brothers. The brothers were declared "Patrons of Europe" in 1980.[37]

The first recorded secular celebration of Saints Cyril and Methodius' Day as the "Day of the Bulgarian script", as traditionally accepted by Bulgarian history, was held in the town of Plovdiv on 11 May 1851. At the same time a local Bulgarian school was named "Saints Cyril and Methodius". Both acts had been instigated by the prominent Bulgarian educator Nayden Gerov.[38] However, an Armenian traveller referred to a "celebration of the Bulgarian script" when he visited the town of Shumen on 22 May 1803.[39]

Cyril and Methodius are remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival[40] and with a lesser feast on the Episcopal Church calendar[1] on 14 February.

The day is now celebrated as a public holiday in the following countries:

- In Bulgaria it is celebrated on 24 May and is known as the "Bulgarian Education and Culture, and Slavonic Script Day" (Bulgarian: Ден на българската просвета и култура и на славянската писменост), a national holiday celebrating Bulgarian culture and literature as well as the alphabet. It is also known as "Alphabet, Culture, and Education Day" (Bulgarian: Ден на азбуката, културата и просвещението). Saints Cyril and Methodius are patrons of the National Library of Bulgaria. There is a monument to them in front of the library. Saints Cyril and Methodius are the most celebrated saints in the Bulgarian Orthodox church, and icons of the two brothers can be found in every church.

- In North Macedonia, it is celebrated on 24 May and is known as the "Saints Cyril and Methodius, Slavonic Enlighteners' Day" (Macedonian: Св. Кирил и Методиј, Ден на словенските просветители), a national holiday. The Government of the Republic of Macedonia enacted a statute of the national holiday in October 2006 and the Parliament of the Republic of Macedonia passed a corresponding law at the beginning of 2007.[41] Previously it had only been celebrated in the schools. It is also known as the day of the "Solun Brothers" (Macedonian: Солунските браќа).

- In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the two brothers were originally commemorated on 9 March, but Pope Pius IX changed this date to 5 July for several reasons.[42] Today, Saints Cyril and Methodius are revered there as national saints and their name day (5 July), "Sts Cyril and Methodius Day" is a national holiday in Czech Republic and Slovakia. In the Czech Republic it is celebrated as "Slavic Missionaries Cyril and Methodius Day" (Czech: Den slovanských věrozvěstů Cyrila a Metoděje); in Slovakia it is celebrated as "St. Cyril and Metod Day" (Slovak: Sviatok svätého Cyrila a Metoda).[42]

- In Russia, it is celebrated on 24 May and is known as the "Slavonic Literature and Culture Day" (Russian: День славянской письменности и культуры), celebrating Slavonic culture and literature as well as the alphabet. Its celebration is ecclesiastical (11 May in the Church's Julian calendar). It is not a public holiday in Russia.

The saints' feast day is celebrated by the Eastern Orthodox Church on 11 May and by the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion on 14 February as "Saints Cyril and Methodius Day". The Lutheran Churches of Western Christianity commemorate the two saints either on 14 February or 11 May. The Byzantine Rite Lutheran Churches celebrate Saints Cyril and Methodius Day on 24 May.[43]

Other commemoration

The national library of Bulgaria in Sofia, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje in the North Macedonia, and St. Cyril and St. Methodius University of Veliko Tarnovo in Bulgaria and in Trnava, Slovakia, bear the name of the two saints. Faculty of Theology at Palacký University in Olomouc (Czech Republic), bears the name "Saints Cyril and Methodius Faculty of Theology". In the United States, SS. Cyril and Methodius Seminary in Orchard Lake, Michigan, bears their name.

The Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius established in 1846 was short-lived a pro-Ukrainian organization in the Russian Empire to preserve Ukrainian national identity.

Saints Cyril and Methodius are the main patron saints of the Archdiocese of Ljubljana. Ljubljana Cathedral stands at Cyril and Methodius Square (Slovene: Ciril–Metodov trg).[44] They are also patron saints of the Greek-Catholic Eparchy of Košice (Slovakia)[5] and the Slovak Greek Catholic Eparchy of Toronto.

St. Cyril Peak and St. Methodius Peak in the Tangra Mountains on Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, in Antarctica are named for the brothers.

Saint Cyril's remains are interred in a shrine-chapel within the Basilica di San Clemente in Rome. The chapel holds a Madonna by Sassoferrato.

The Basilica of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Danville, Pennsylvania, (the only Roman Catholic basilica dedicated to SS. Cyril and Methodius in the world) is the motherhouse chapel of the Sisters of SS. Cyril and Methodius, a Roman Catholic women's religious community of pontifical right dedicated to apostolic works of ecumenism, education, evangelization, and elder care.[45]

The Order of Saints Cyril and Methodius, originally founded in 1909, is part of the national award system of Bulgaria.

In 2021, a research vessel newly acquired by the Bulgarian Navy was re-christened Ss. Cyril and Methodius after the saints, with actress Maria Bakalova as the sponsor.[46]

Gallery

-

Cross Procession in Khanty-Mansiysk on Saints Cyril and Methodius Day in May 2006

-

Inauguration of the monument to Saints Cyril and Methodius in Saratov on Slavonic Literature and Culture Day

-

Thessaloniki - monument of the two Saints gift from the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

-

Bulgaria - Statue of the two Saints in front of the SS. Cyril and Methodius National Library in Sofia

-

North Macedonia - The monument in Ohrid

-

Czech Republic - Saints Cyril and Methodius monument in Mikulčice

-

Russia - the monument in Khanty-Mansiysk

-

Opening of Cyril and Methodius monument in Donetsk

-

Statue, Saints Cyril and Methodius, Třebíč, Czech Republic

Names in other relevant languages

- Armenian: Կիրիլ և Մեթոդիոս (Kiril ev Metodios)

- Greek: Κύριλλος καὶ Μεθόδιος (Kýrillos kaí Methódios)

- Old Church Slavonic: Кѷриллъ и Меѳодїи

- Belarusian: Кірыла і Мяфодзій (Kiryła i Miafodzij) or Кірыла і Мятода (Kiryła i Miatoda)

- Bulgarian: Кирил и Методий (Kiril i Metodiy)

- Croatian: Ćiril i Metod

- Czech: Cyril a Metoděj

- Kazakh: Кирилл және методиус (Kïrïll jäne metodïws)

- Macedonian: Кирил и Методиј (Kiril i Metodij)

- New Church Slavonic: Кѷрі́ллъ и҆ Меѳо́дїй (Kỳrill" i Methodij)

- Polish: Cyryl i Metody

- Romanian: Chiril și Metodiu

- Russian: Кири́лл и Мефодий (Kirill i Mefodij), pre-1918 spelling: Кириллъ и Меѳодій (Kirill" i Methodij)

- Serbian: Ћирило и Методије / Ćirilo i Metodije

- Slovak: Cyril a Metod

- Slovene: Ciril in Metod

- Ukrainian: Кирило і Мефодій (Kyrylo i Mefodij)

See also

- Cyrillo-Methodian studies

- Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Byzantine Empire

- Glagolitic alphabet

- SS. Cyril and Methodius Seminary in Orchard Lake, Michigan, United States

- SS. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje in Skopje, North Macedonia

- “St. St. Cyril and Methodius” National Library in Sofia, Bulgaria

- University of Veliko Turnovo St Cyril and St. Methodius in Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria

- Saints Cyril and Methodius Faculty of Theology, Palacký University of Olomouc in Olomouc, Czech Republic

References

Citations

- ^ a b "Cyril and Methodius, Missionaries, 869, 885". The Episcopal Church. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Notable Lutheran Saints". Resurrectionpeople.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ In the 21st century this date in the Julian Calendar corresponds to 24 May in the Gregorian Calendar

- ^ a b Jones, Terry. "Methodius". Patron Saints Index. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- ^ a b History of the Eparchy of Košice Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine (Slovak)

- ^ "Figures of (trans-) national religious memory of the Orthodox southern Slavs before 1945: an outline on the examples of SS. Cyril and Methodius". ResearchGate. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Liturgy of the Hours, Volume III, 14 February.

- ^ "Egregiae Virtutis". Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009. Apostolic letter of Pope John Paul II, 31 December 1980 (in Latin)

- ^ Cyril and Methodius, Encyclopædia Britannica 2005

- ^ Vita Constantini slavica, Cap. 18: Denkschriften der kaiserl. Akademie der Wissenschaften 19, Wien 1870, p. 246

- ^ Chapter 18 of the Slavonic Life of Constantine Archived 15 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, an English translation

- ^ English Translation of the 18th Chapter of the Vita Constantini, Liturgy of the Hours, Proper of Saints, 14 February

- ^ "SS.Cyril and Methodius". www.carpatho-rusyn.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^

- 1. Mortimer Chambers, Barbara Hanawalt, Theodore Rabb, Isser Woloch, Raymond Grew. The Western Experience with Powerweb. Eighth Edition. McGraw-Hill Higher Education 2002. University of Michigan. p. 214. ISBN 9780072565447

- 2. Balkan Studies, Volume 22. Hidryma Meletōn Chersonēsou tou Haimou (Thessalonikē, Greece). The Institute, 1981. Original from the University of Michigan. p. 381

- 3. Loring M. Danforth. The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press, 1995. p. 49 ISBN 9780691043562.

- 4. Ihor Ševčenko. Byzantium and the Slavs: In Letters and Culture'. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 1991. p. 481. ISBN 9780916458126

- 5. Roland Herbert Bainton. Christianity: An American Heritage Book Series. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000. p. 156. ISBN 9780618056873

- 6. John Shea. Macedonia and Greece: The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation. McFarland, 1997. p. 56 . ISBN 9780786437672

- 7. UNESCO Features: A Fortnightly Press Service. UNESCO. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 1984. University of Michigan

- 8. The Pakistan Review, Volume 19. Ferozsons Limited, 1971. University of California. p. 41

- 9. Balkania, Volume 7. Balkania Publishing Company, 1973. Indiana University. p. 10

- 10. Bryce Dale Lyon, Herbert Harvey Rowen, Theodore S. Hamerow. A History of the Western World, Volume 1. Rand McNally College Pub. Co., 1974. Northwestern University. p. 239

- 11. Roland Herbert Bainton. The history of Christianity. Nelson, 1964. p. 169

- 12. Carl Waldman, Catherine Mason. Encyclopedia of European Peoples: Facts on File library of world history. Infobase Publishing, 2006. p. 752. ISBN 9781438129181

- 13. Frank Andrews. Ancient Slavs'. Worzalla Publishing Company, 1976. University of Wisconsin - Madison. p. 163.

- 14. Johann Heinrich Kurtz, John Macpherson. Church History. Hodder and Stoughton, 1891. University of California. p. 431

- 15. William Leslie King. Investment and Achievement: A Study in Christian Progress. Jennings and Graham, 1913. Columbia University.

- ^

- Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05, s.v. "Cyril and Methodius, Saints" "Greek missionaries, brothers, called Apostles to the Slavs and fathers of Slavonic literature."

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Major alphabets of the world, Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, 2008, O.Ed. "The two early Slavic alphabets, the Cyrillic and the Glagolitic, were invented by St. Cyril, or Constantine (c. 827–869), and St. Methodius (c. 825–884). These men were Greeks from Thessalonica who became apostles to the southern Slavs, whom they converted to Christianity.

- Encyclopedia of World Cultures, David H. Levinson, 1991, p.239, s.v., "Social Science"

- Eric M. Meyers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, p.151, 1997

- Lunt, Slavic Review, June 1964, p. 216; Roman Jakobson, Crucial problems of Cyrillo-Methodian Studies; Leonid Ivan Strakhovsky, A Handbook of Slavic Studies, p.98

- V.Bogdanovich, History of the ancient Serbian literature, Belgrade, 1980, p.119

- Hastings, Adrian (1997). The construction of nationhood: ethnicity, religion, and nationalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-521-62544-0.

The activity of the brothers Constantine (later renamed Cyril) and Methodius, aristocratic Greek priests who were sent from Constantinople.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1999). The barbarian conversion: from paganism to Christianity. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-520-21859-0.

- Cizevskij, Dmitrij; Zenkovsky, Serge A.; Porter, Richard E. (1971). Comparative History of Slavic Literatures. Vanderbilt University Press. p. vi. ISBN 0-8265-1371-9.

Two Greek brothers from Salonika, Constantine who later became a monk and took the name Cyril and Methodius.

- The illustrated guide to the Bible. New York: Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 14. ISBN 0-19-521462-5.

In Eastern Europe, the first translations of the Bible into the Slavonic languages were made by the Greek missionaries Cyril and Methodius in the 860s

- Smalley, William Allen (1991). Translation as mission: Bible translation in the modern missionary movement. Macon, Ga.: Mercer. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-86554-389-8.

The most important instance where translation and the beginning church did coincide closely was in Slavonic under the brothers Cyril and Methodius, with the Bible completed by A.D. 880. This was a missionary translation but unusual again (from a modern point of view) because not a translation into the dialect spoken where the missionaries were. The brothers were Greeks who had been brought up in Macedonia.

- ^

- 1. Philip Lief Group. Saintly Support: A Prayer For Every Problem. Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2003. p. 37. ISBN 9780740733369

- 2. UNESCO Features: A Fortnightly Press Service. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization., 1984. University of Michigan

- ^ Raymond Davis (1995). The Lives of the Ninth-century Popes (Liber Pontificalis): The Ancient Biographies of Ten Popes from A.D. 817-891. Liverpool University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-85323-479-1.

- ^ "Pope Benedict XVI. "Saints Cyril and Methodius", General Audience 17 June 2009, Libreria Editrice Vaticana". W2.vatican.va. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Vizantiiskoe missionerstvo, Ivanov S. A., Iazyki slavianskoi kul'tury, Moskva 2003, p. 147

- ^ a b c Encyclopædia Britannica, Cyril and Methodius, Saints, O.Ed., 2008

- ^ "From Eastern Roman to Byzantine: transformation of Roman culture (500-800)". Indiana University Northwest. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ a b Abraham, Ladislas (1908). "Sts. Cyril and Methodius". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Sts. Cyril and Methodius". Pravmir. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Vir apostolicae vitae...sapientissimus vir" MGH Epist., 7/2, 1928, p. 436

- ^ "Sv. Gorazd a spoločníci" [St. Gorazd and his colleagues]. Franciscan Friars of Slovakia (in Slovak). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ David Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Fifth Edition Revised, OUP Oxford, 2011, ISBN 0191036730, p. 94.

- ^ "Seven Saints". Kashtite.com. 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ It was and is customary on becoming a monk in the Eastern Orthodox tradition to receive a new name.

- ^ Đorđe Radojičić (1971). Živan Milisavac (ed.). Jugoslovenski književni leksikon [Yugoslav Literary Lexicon] (in Serbo-Croatian). Novi Sad (SAP Vojvodina, SR Serbia): Matica srpska. pp. 73–75.

- ^ Bowlus 1995, p. 165-186.

- ^ Goldberg 2006, p. 319-320.

- ^ Житїе Меөодїя (Life of Methodius), title & chap. XVIII - available on-line Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Short Life of Cyril & Methodius. Translated by Ján STANISLAV: Životy slovanských apoštolov Cyrila a Metoda v legendách a listoch. Turčiansky Sv. Martin: Matica slovenská, 1950, p. 88. (Slovak)

- ^ Richard P. McBrien, Lives of the Popes, (HarperCollins, 2000), 144.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Major alphabets of the world, Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, 2008, O.Ed. "The two early Slavic alphabets, the Cyrillic and the Glagolitic, were invented by St. Cyril, or Constantine (c. 827–869), and St. Methodius (c. 825–884). These men were Greeks from Thessalonica who became apostles to the southern Slavs, whom they converted to Christianity.

- ^ "In Pictures: Ohrid, Home of Cyrillic". Balkan Insight. 24 May 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ "Nikolaos Martis: MACEDONIA". www.hri.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "История на България", Том 6 Българско Възраждане 1856–1878, Издателство на Българската академия на науките, София, 1987, стр. 106 (in Bulgarian; in English: "History of Bulgaria", Volume 6 Bulgarian Revival 1856–1878, Publishing house of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, 1987, page 106).

- ^ Jubilee speech of the Academician Ivan Yuhnovski, Head of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, held on 23 May 2003, published in Information Bulletin Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 3(62), Sofia, 27 June 2003 (in Bulgarian).

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Announcement about the eleventh session of the Government of the Republic of Macedonia on 24 October 2006 from the official site Archived 10 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine of the Government of the Republic of Macedonia (in Macedonian).

- ^ a b Votruba, Martin. "Holiday date". Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ^ "День Св. Кирила та Мефодія, просвітителів слов'янських" (in Ukrainian). Ukrainian Lutheran Church. 24 May 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "The Ljubljana Metropolitan Province". 5 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Sisters of Saints Cyril and Methodius". Sscm.org. 4 March 2002. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Bulgaria's First Military Research Vessel Christened Ss. Cyril and Methodius". Bulgarian Telegraph Agency. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

Sources

- Betti, Maddalena (2013). The Making of Christian Moravia (858-882): Papal Power and Political Reality. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004260085.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1995). Franks, Moravians, and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788-907. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812232769.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815390.

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004395190.

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813507996.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472081497.

- Goldberg, Eric J. (2006). Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict under Louis the German, 817-876. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801438905.

- Komatina, Predrag (2015). "The Church in Serbia at the Time of Cyrilo-Methodian Mission in Moravia". Cyril and Methodius: Byzantium and the World of the Slavs. Thessaloniki: Dimos. pp. 711–718.

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Subotin-Golubović, Tatjana (1999). "Reflection of the Cult of Saint Konstantine and Methodios in Medieval Serbian Culture". Thessaloniki - Magna Moravia: Proceedings of the International Conference. Thessaloniki: Hellenic Association for Slavic Studies. pp. 37–46. ISBN 9789608595934.

- Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521074599.

- Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Orthodox Byzantium, 600–1025. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 9781349247653.

Further reading

- Dvornik, F. (1964). "The Significance of the Missions of Cyril and Methodius". Slavic Review. 23 (2): 195–211. doi:10.2307/2492930. JSTOR 2492930. S2CID 163378481.

External links

- Slavorum Apostoli by Pope John Paul II

- Cyril and Methodius – Encyclical letter (Epistola Enciclica), 31 December 1980 by Pope John Paul II

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Equal to Apostles SS. Cyril and Methodius Teachers of Slavs", by Prof. Nicolai D. Talberg

- Pope Leo XIII, "Grande munus: on Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Bulgarian Official Holidays, National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria: in English Archived 9 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, in Bulgarian Archived 28 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Bank holidays in the Czech Republic, Czech National Bank: in English, in Czech

- 24 May – The Day Of Slavonic Alphabet, Bulgarian Enlightenment and Culture

- 815 births

- 827 births

- 869 deaths

- 885 deaths

- Brother duos

- Eastern Christianity in the Czech Republic

- Byzantine Thessalonians

- Saints of medieval Macedonia

- Saints of medieval Greece

- Greek translators

- Translators of the Bible into Church Slavonic

- Byzantine theologians

- Cyrillic script

- Saints duos

- Great Moravia

- Public holidays in Russia

- Creators of writing systems

- Greek Christian missionaries

- Medieval Bulgarian saints

- Old Church Slavonic writers

- 9th-century Christian saints

- Burials at San Clemente al Laterano

- Groups of Roman Catholic saints

- Groups of Eastern Orthodox saints

- 9th-century Christian theologians

- 9th-century Byzantine writers

- Cyrillo-Methodian studies

- Anglican saints

- Missionary linguists

- Rusyn history

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !