Salvadoran Civil War

| Salvadoran Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Central American crisis and the Cold War | |||||||

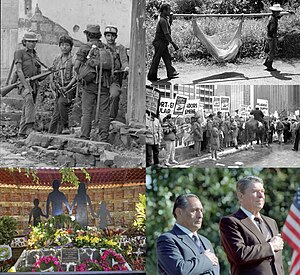

Clockwise from top right: two Salvadorans carrying a casualty of war, an anti-war protest in Chicago, Salvadoran President José Napoleón Duarte and U.S. President Ronald Reagan, a memorial to the El Mozote massacre, ERP fighters in Perquín | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,360+ killed[23] | 12,274[23] – 20,000 killed[24] | ||||||

|

65,161+ civilians killed[23] 5,292+ disappeared[23] 550,000 internally displaced 500,000 refugees in other countries[19][25][26] | |||||||

The Salvadoran Civil War (Spanish: guerra civil de El Salvador) was a twelve-year civil war in El Salvador that was fought between the government of El Salvador, backed by the United States,[27] and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a coalition of left-wing guerilla groups backed by the Cuban regime of Fidel Castro as well as the Soviet Union.[4] A coup on 15 October 1979 followed by government killings of anti-coup protesters is widely seen as the start of civil war.[28][a] The war did not formally end until after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when, on 16 January 1992 the Chapultepec Peace Accords were signed in Mexico City.[29]

The United Nations (UN) reports that the war killed more than 75,000 people between 1979 and 1992, along with approximately 8,000 disappeared persons. Human rights violations, particularly the kidnapping, torture, and murder of suspected FMLN sympathizers by state security forces and paramilitary death squads – were pervasive.[30][31][32]

The Salvadoran government was considered an ally of the U.S. in the context of the Cold War.[33] During the Carter and Reagan administrations, the US provided economic aid to the Salvadoran government.[34] The US also provided significant training and equipment to the military. By May 1983, it was reported that US military officers were working within the Salvadoran High Command and making important strategic and tactical decisions.[35] The United States government believed its extensive assistance to El Salvador's government was justified on the grounds that the insurgents were backed by the Soviet Union.[36]

Counterinsurgency tactics implemented by the Salvadoran government often targeted civilians. Overall, the United Nations estimated that FMLN guerrillas were responsible for 5 percent of atrocities committed during the civil war, while 85 percent were committed by the Salvadoran security forces.[37]

Accountability for these civil war-era atrocities has been hindered by a 1993 amnesty law. In 2016, however, the Supreme Court of Justice of El Salvador ruled in case Incostitucionalidad 44-2013/145-2013[38] that the law was unconstitutional and that the Salvadoran government could prosecute suspected war criminals.[39]

Background

El Salvador has historically been characterised by extreme socioeconomic inequality.[40] In the late 19th century, coffee became a major cash crop for El Salvador.[41] The divide between rich and poor grew through the 1920s and was compounded by a drop in coffee prices following the stock-market crash of 1929.[42][43] In 1932, the Central American Socialist Party was formed and led an uprising of peasants and indigenous people against the government. The FMLN was named after Farabundo Martí, one of the leaders of the uprising.[44] The rebellion was brutally suppressed in La Matanza, during which approximately 30,000 civilians were murdered by the armed forces.[45] La Matanza – 'the slaughter' in Spanish, as it came to be known – allowed military dictatorships to monopolize political power in El Salvador while protecting the economic dominance of the landed elite.[45] Opposition to this arrangement among middle-class, working-class, and poor Salvadorans grew throughout the 20th century.[45]

On 14 July 1969, an armed conflict erupted between El Salvador and Honduras over immigration disputes caused by Honduran land reform laws. The conflict (known as the Football War) lasted only four days but had major long-term effects for Salvadoran society. Trade was disrupted between El Salvador and Honduras, causing tremendous economic damage to both nations. An estimated 300,000 Salvadorans were displaced due to battle, many of whom were exiled from Honduras; in many cases, the Salvadoran government could not meet their needs. The Football War also strengthened the power of the military in El Salvador, leading to heightened corruption. In the years following the war, the government expanded its purchases of arms from sources such as Israel, Brazil, West Germany and the United States.[46]

The 1972 Salvadoran presidential election was marred by massive electoral fraud, which favored the military-backed National Conciliation Party (PCN), whose candidate Arturo Armando Molina was a colonel in the Salvadoran Army. Opposition to the Molina government was strong on both the right and the left. Also in 1972, the Marxist–Leninist Fuerzas Populares de Liberación Farabundo Martí (FPL) – established in 1970 as an offshoot of the Communist Party of El Salvador – began conducting small-scale guerrilla operations in El Salvador. Other organizations such as the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP) also began to develop.

The growth of left-wing insurgency in El Salvador occurred against a backdrop of rising food prices and decreased agricultural output exacerbated by the 1973 oil crisis. This worsened the existing socioeconomic inequality in the country, leading to increased unrest. In response, President Molina enacted a series of land reform measures, calling for large landholdings to be redistributed among the peasant population. The reforms failed, thanks to opposition from the landed elite, reinforcing the widespread discontent with the government.[47]

On 20 February 1977, the PCN defeated the National Opposition Union (UNO) in the presidential elections. As was the case in 1972, the results of the 1977 election were fraudulent and favored a military candidate, General Carlos Humberto Romero. State-sponsored paramilitary forces – such as the infamous Organización Democrática Nacionalista (ORDEN) – reportedly strong-armed peasants into voting for the military candidate by threatening them with machetes.[48] The period between the election and the formal inauguration of President Romero on 1 July 1977 was characterized by massive protests from the popular movement, which were met by state repression. On 28 February 1977, a crowd of political demonstrators gathered in downtown San Salvador to protest the electoral fraud. Security forces arrived on the scene and opened fire, resulting in a massacre as they indiscriminately killed demonstrators and bystanders alike. Estimates of the number of civilians killed range between 200[49] and 1,500.[50]: 109–110 President Molina blamed the protests on "foreign Communists" and immediately exiled a number of top UNO party members from the country.[51]

Repression continued after the inauguration of President Romero, with his new government declaring a state-of-siege and suspending civil liberties. In the countryside, the agrarian elite organized and funded paramilitary death squads, such as the infamous Regalado's Armed Forces (FAR) led by Hector Regalado. While the death squads were initially autonomous from the Salvadoran military and composed of civilians (the FAR, for example, had developed out of a Boy Scout troop), they were soon taken over by El Salvador's military intelligence service, National Security Agency of El Salvador (ANSESAL), led by Major Roberto D'Aubuisson, and became a crucial part of the state's repressive apparatus, murdering thousands of union leaders, activists, students and teachers suspected of sympathizing with the left.[52] The Socorro Jurídico Cristiano (Christian Legal Assistance) – a legal aid office within the archbishop's office and El Salvador's leading human rights group at the time – documented the killings of 687 civilians by government forces in 1978. In 1979 the number of documented killings increased to 1,796.[53][50]: 1–2, 222 The repression prompted many in the Catholic Church to denounce the government, which responded by repressing the clergy.[54]

Historian M. A. Serpas[citation needed] posits displacement and dispossession rates with respect to land as a major structural factor leading ultimately to civil war. El Salvador is an agrarian society, with coffee fueling its economy, where "77 percent of the arable land belonged to .01 percent of the population. Nearly 35 percent of the civilians in El Salvador were disfranchised from land ownership either through historical injustices, war or economic downturns in the commodities market. During this time frame, the country also experienced a growing population amidst major disruption in agrarian commerce and trade."[citation needed]

A threat to land change meant a challenge to a state where "marriages intertwined, making the wealthiest coffee processors and exporters (more so than the growers) also those with the highest ties in the military.

— M. A. Serpas

Coup d'état, repression and insurrection: 1979–1981

Military coup October 1979

With tensions mounting and the country on the verge of an insurrection, the civil-military Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG) deposed Romero in a coup on 15 October 1979. The United States feared that El Salvador, like Nicaragua and Cuba before it, could fall to communist revolution.[55] Thus, Jimmy Carter's administration supported the new military government with vigor, hoping to promote stability in the country.[56] While Carter provided some support to the government, the subsequent Reagan administration significantly increased U.S. spending in El Salvador.[57] By 1984 Ronald Reagan's government would spend nearly $1 billion on economic aid for the Salvadoran government.[58]

The JRG enacted a land reform program that restricted landholdings to a 100-hectare maximum, nationalised the banking, coffee and sugar industries, scheduled elections for February 1982, and disbanded the paramilitary private death squad Organización Democrática Nacionalista (ORDEN) on 6 November 1979.[59]

The land reform program was received with hostility from El Salvador's military and economic elites, however, which sought to sabotage the process as soon as it began. Upon learning of the government's intent to distribute land to the peasants and organize cooperatives, wealthy Salvadoran landowners began killing their own livestock and moving valuable farming equipment across the border into Guatemala, where many Salvadoran elites owned additional land. In addition, most co-op leaders in the countryside were assassinated or "disappeared" soon after being elected and becoming visible to the authorities.[60] The Socorro Jurídico documented a jump in documented government killings from 234 in February 1980 to 487 the following month.[1]: 270

Under pressure from the military, all three civilian members of the junta resigned on 3 January 1980, along with 10 of the 11 cabinet ministers. On 22 January 1980, the Salvadoran National Guard attacked a massive peaceful demonstration, killing up to 50 people and wounding hundreds more.[59] On 6 February, US ambassador Frank Devine informed the State Department that the extreme right was arming itself and preparing for a confrontation in which it clearly expected to ally itself with the military.[61][62]

Criticism of US support

"The immediate goal of the Salvadoran army and security forces—and of the United States in 1980, was to prevent a takeover by the leftist-led guerrillas and their allied political organizations. At this point in the Salvadoran conflict the latter were much more important than the former. The military resources of the rebels were extremely limited and their greatest strength, by far, lay not in force of arms but in their 'mass organizations' made up of labor unions, student and peasant organizations that could be mobilized by the thousands in El Salvador's major cities and could shut down the country through strikes."[63]

Critics of US military aid charged that "it would legitimate what has become dictatorial violence and that political power in El Salvador lay with old-line military leaders in government positions who practice a policy of 'reform with repression.'" A prominent Catholic spokesman insisted that "any military aid you send to El Salvador ends up in the hands of the military and paramilitary rightist groups who are themselves at the root of the problems of the country."[64]

"In one case that has received little attention", Human Rights Watch noted, "US Embassy officials apparently collaborated with the death squad abduction of two law students in January 1980. National Guard troops arrested two youths, Francisco Ventura and José Humberto Mejía, following an anti-government demonstration. The National Guard received permission to bring the youths onto Embassy grounds. Shortly thereafter, a private car drove into the Embassy parking lot. Men in civilian dress put the students in the trunk of their car and drove away. Ventura and Mejía were never seen again."[65]

Motivation for the resistance

As the government began to expand its violence towards its citizens, not only through death squads but also through the military, any group of citizens that attempted to provide any form of support whether physically or verbally ran the risk of death. Even so, many still chose to participate.[66] But the violence was not limited to activists but also anyone who promoted ideas that "questioned official policy" were tacitly assumed to be subversive against the government.[67] A marginalized group that metamorphosed into a guerilla force that would end up confronting these government forces manifested itself in campesinos or peasants. Many of these insurgents joined collective action campaigns for material gain; in the Salvadoran Civil War, however, many peasants cited reasons other than material benefits in their decision to join the fight.[68]

Piety was a popular reason for joining the insurrection because they saw their participation as a way of not only advancing a personal cause but a communal sentiment of divine justice.[69] Even prior to the civil war, numerous insurgents took part in other campaigns that tackled social changes much more directly, not only the lack of political representation but also the lack of economic and social opportunities not afforded to their communities.[70]

While the FMLN can be characterized as an insurrectionist group, other scholars have classified it as an "armed group institution." Understanding the differentiation is crucial. Armed group institutions use tactics to reinforce their mission or ideology. Ultimately influencing the behavior and group norms of their combatants. In this regard, the FMLN had a more effective approach than El Salvador's army in politically educating their members about their mission. Individuals who aligned themselves with the FMLN were driven by a profound sense of passion and purpose. They demonstrated a willingness to risk their lives for the greater good of their nation. The FMLN strategy focused on community organization, establishing connections within the church and labor unions. In contrast, El Salvador's army had inadequate training, and many of its combatants reported joining out of job insecurity or under intimidation from the government.These disparities were notably reflected in their respective combat methods. Further, the Salvadoran military caused more civilian casualties than the FMLN.[71]

In addition, the insurgents in the civil war viewed their support of the insurrection as a demonstration of their opposition to the powerful elite's unfair treatment of peasant communities that they experienced on an everyday basis, so there was a class element associated with these insurgencies.[72] They reveled in their fight against injustice and in their belief that they were writing their own story, an emotion that Elisabeth Wood titled "pleasure of agency".[73] The peasants' organization thus centered on using their struggle to unite against their oppressors, not only towards the government but the elites as well, a struggle that soon evolved into a political machine that came to be associated with the FMLN.

In the early months of 1980, Salvadoran guerilla groups, workers, communists, and socialists, unified to form the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN).[44] The FMLN immediately announced plans for an insurrection against the government, which began on 10 January 1981, with the FMLN's first major attack. The attack established FMLN control of most of Morazán and Chalatenango departments for the war's duration. Attacks were also launched on military targets throughout the country, leaving hundreds of people dead. FMLN insurgents ranged from children to the elderly, both male and female, and most were trained in FMLN camps in the mountains and jungles of El Salvador to learn military techniques.

Much later, in November 1989, the FMLN launched a large offensive that caught Salvadoran military off guard and succeeded in taking control of large sections of the country and entering the capital, San Salvador. In San Salvador, the FMLN quickly took control of many of the poor neighborhoods as the military bombed their positions—including residential neighborhoods to drive out the FMLN. This large FMLN offensive was unsuccessful in overthrowing the government but did convince the government that the FMLN could not be defeated using force of arms and that a negotiated settlement would be necessary.[74]

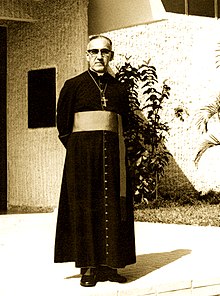

Assassination of Archbishop Romero

In February 1980, Archbishop Óscar Romero published an open letter to US President Jimmy Carter in which he pleaded with him to suspend the United States' ongoing program of military aid to the Salvadoran regime. He advised Carter that "Political power is in the hands of the armed forces. They know only how to repress the people and defend the interests of the Salvadoran oligarchy." Romero warned that US support would only "sharpen the injustice and repression against the organizations of the people which repeatedly have been struggling to gain respect for their fundamental human rights".[75] On 24 March 1980, the Archbishop was assassinated while celebrating Mass, the day after he called upon Salvadoran soldiers and security force members to not follow their orders to kill Salvadoran civilians. President Carter stated this was a "shocking and unconscionable act".[76] At his funeral a week later, government-sponsored snipers in the National Palace and on the periphery of the Gerardo Barrios Plaza were responsible for the shooting of 42 mourners.[77]

On 7 May 1980, former army major, Roberto D'Aubuisson, was arrested with a group of civilians and soldiers at a farm. The raiders found documents connecting him and the civilians as organizers and financiers of the death squad who killed Archbishop Romero, and of plotting a coup d'état against the JRG. Their arrest provoked right-wing terrorist threats and institutional pressures forcing the JRG to release D'Aubuisson. In 1993, a U.N. investigation confirmed that D'Aubuisson ordered the assassination.[78]

A week after the arrest of D'Aubuisson, the National Guard and the newly reorganized paramilitary ORDEN, with the cooperation of the Military of Honduras, carried out a large massacre at the Sumpul River on 14 May 1980, in which an estimated 600 civilians were killed, mostly women and children. Escaping villagers were prevented from crossing the river by the Honduran armed forces, "and then killed by Salvadoran troops who fired on them in cold blood".[79] Over the course of 1980, the Salvadoran Army and three main security forces (National Guard, National Police and Treasury Police) were estimated to have killed 11,895 people, mostly peasants, trade unionists, teachers, students, journalists, human rights advocates, priests, and other prominent demographics among the popular movement.[53] Human rights organizations judged the Salvadoran government to have among the worst human rights records in the hemisphere.[80]

Murder and rape of US nuns

On 2 December 1980, members of the Salvadoran National Guard were suspected to have raped and murdered four American, Catholic church women (three religious women, or nuns, and a laywoman). Maryknoll missionary sisters Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, Ursuline sister Dorothy Kazel, and laywoman Jean Donovan were on a Catholic relief mission providing food, shelter, transport, medical care, and burial to death squad victims. In 1980 alone, at least 20 religious workers and priests were murdered in El Salvador. Throughout the war, the murders of church figures increased. For example, the Jesuit University of Central America stated that two bishops, sixteen priests, three nuns, one seminarian, and at least twenty-seven lay workers were murdered. By killing Church figures, "the military leadership showed just how far its position had hardened in daring to eliminate those it viewed as opponents. They saw the Church as an enemy that went against the military and their rule."[81] U.S. military aid was briefly cut off in response to the murders but was renewed within six weeks. The outgoing Carter administration increased military aid to the Salvadoran armed forces to $10 million, which included $5 million in rifles, ammunition, grenades and helicopters.[82]

In justifying these arms shipments, the administration claimed that the regime had taken "positive steps" to investigate the murder of four American nuns, but this was disputed by US Ambassador, Robert E. White, who said that he could find no evidence the junta was "conducting a serious investigation".[82] White was dismissed from the foreign service by the Reagan administration after he had refused to participate in a coverup of the Salvadoran military's responsibility for the murders at the behest of Secretary of State Alexander Haig.[83]

Repression stepped up

Other countries allied with the United States also intervened in El Salvador. The military government in Chile provided substantial training and tactical advice to the Salvadoran Armed Forces, such that the Salvadoran high command bestowed upon General Augusto Pinochet the prestigious Order of José Matías Delgado in May 1981 for his government's avid support. The Argentine military dictatorship also supported the Salvadoran armed forces as part of Operation Charly.

During the same month, the JRG strengthened the state of siege, imposed by President Romero in May 1979, by declaring martial law and adopting a new set of curfew regulations.[84] Between 12 January and 19 February 1981, 168 persons were killed by the security forces for violating curfew.[85]

"Draining the Sea"

In its effort to defeat the insurgency, the Salvadoran Armed Forces carried out a "scorched earth" strategy, and adopted tactics similar to those being employed in neighboring Guatemala by its security forces. These tactics were inspired and adapted from U.S. counterinsurgency strategies used during the Vietnam War.[86] An integral part of the Salvadoran Army's counterinsurgency strategy entailed "draining the sea" or "drying up the ocean", that is, eliminating the insurgency by eradicating its support base in the countryside. The primary target was the civilian population – displacing or killing them in order to remove any possible base of support for the rebels. The concept of "draining the sea" had its basis in a doctrine by Mao Zedong that emphasized that "The guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea."[87]

Aryeh Neier, the executive director of Americas Watch, wrote in a 1984 review about the scorched earth approach: "This may be an effective strategy for winning the war. It is, however, a strategy that involves the use of terror tactics—bombings, strafings, shellings and, occasionally, massacres of civilians."[88]

Beginning in 1984, the Salvadoran Air Force was able to locate guerrilla strongholds reportedly using intelligence from U.S. Air Force planes flying over the country.[89][90]

Scorched earth offensives of 1981

On 15 March 1981, the Salvadoran Army began a "sweep" operation in Cabañas Department in northern El Salvador near the Honduran border. The sweep was accompanied by the use of scorched earth tactics by the Salvadoran Army and indiscriminate killings of anyone captured by the army. Those displaced by the "sweep" who were not killed outright fled the advance of the Salvadoran Army; hiding in caves and under trees to evade capture and probable summary execution. On 18 March, three days after the sweep in Cabañas began, 4–8,000 survivors of the sweep (mostly women and children) attempted to cross the Rio Lempa into Honduras to flee violence. There, they were caught between Salvadoran and Honduran troops. The Salvadoran Air Force, subsequently bombed and strafed the fleeing civilians with machine gun fire, killing hundreds. Among the dead were at least 189 persons who were unaccounted for and registered as "disappeared" during the operation.[91]

A second offensive was launched, also in Cabañas Department, on 11 November 1981 in which 1,200 troops were mobilized, including members of the Atlácatl Battalion. Atlácatl was a rapid response counter-insurgency battalion organized at the U.S. Army School of the Americas in Panama in 1980. Atlácatl soldiers were trained and equipped by the U.S. military,[92][93] and were described as "the pride of the United States military team in San Salvador. Trained in antiguerrilla operations, the battalion was intended to turn a losing war around."[94]

The November 1981 operation was commanded by Lt. Col. Sigifredo Ochoa, a former Treasury Police chief with a reputation for brutality. Ochoa was close associate of Major Roberto D'Aubuisson and was alleged to have been involved in the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero. D'Aubuisson and Ochoa were both members of La Tandona, the class of 1966 at the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School.[95] From the start, the invasion of Cabanas was described as a "cleansing" operation by official sources.[96] Hundreds of civilians were massacred by the army as Col. Ochoa's troops moved through the villages. Col. Ochoa claimed that hundreds of guerrillas had been killed but was able to show journalists only fifteen captured weapons, half of them virtual antiques, suggesting that most of those killed in the sweep were unarmed.[97]

El Mozote massacre

This operation was followed by additional "sweeps" through Morazán Department, spearheaded by the Atlácatl Battalion. On 11 December 1981, one month after the "sweep" through Cabañas, the Battalion occupied the village of El Mozote and massacred at least 733 and possibly up to 1,000 unarmed civilians, including women and 146 children, in what became known as the El Mozote massacre.[98][99] The Atlácatl soldiers accused the adults of collaborating with the guerrillas. The field commander said they were under orders to kill everyone, including the children, who he asserted would just grow up to become guerrillas if they let them live. "We were going to make an example of these people," he said.[100]

The US steadfastly denied the existence of the El Mozote massacre, dismissing reports of it as leftist "propaganda", until secret US cables were declassified in the 1990s.[101] The US government and its allies in US media smeared reporters of American newspapers who reported on the atrocity and, more generally, undertook a campaign of whitewashing the human rights record of the Salvadoran military and the US role in arming, training and guiding it. The smears, according to journalists like Michael Massing writing in the Columbia Journalism Review and Anthony Lewis, made other American journalists tone down their reporting on the crimes of the Salvadoran regime and the US role in supporting the regime.[94][102][103][92][93][104] As details became more widely known, the event became recognized as one of the worst atrocities of the conflict.

In its report covering 1981, Amnesty International identified "regular security and military units as responsible for widespread torture, mutilation and killings of noncombatant civilians from all sectors of Salvadoran society." The report also stated that the killing of civilians by state security forces became increasingly systematic with the implementation of more methodical killing strategies, which allegedly included use of a meat packing plant to dispose of human remains.[105] Between 20 and 25 August 1981, eighty-three decapitations were reported. The murders were later revealed to have been carried out by a death squad using a guillotine.[106]

The repression in rural areas resulted in the displacement of large portions of the rural populace, and many peasants fled. Of those who fled or were displaced, some 20,000 resided in makeshift refugee centers on the Honduran border in conditions of poverty, starvation and disease.[107] The army and death squads forced many of them to flee to the United States, but most were denied asylum.[108] A US congressional delegation that, on 17–18 January 1981, visited the refugee camps in El Salvador on a fact finding mission, submitted a report to Congress that found: "[T]he Salvadoran method of 'drying up the ocean' is to eliminate entire villages from the map, to isolate the guerrillas, and deny them any rural base off which they can feed."[109]

In total, Socorro Jurídico registered 13,353 individual cases of summary execution by government forces over the course of 1981. Nonetheless, the true figure for the number of persons killed by the Army and security services could be substantially higher, due to the fact that extrajudicial killings generally went unreported in the countryside and many of the victims' families remained silent in fear of reprisal. An Americas Watch report described that the Socorro Jurídico figures "tended to be conservative because its standards of confirmation are strict"; killings of persons were registered individually and required proof of being "not combat related".[110] Socorro Jurídico later revised its count of government killings for 1981 up to 16,000 with the induction of new cases.[111][112]

Lieutenant Colonel Domingo Monterrosa was chosen to replace Colonial Jaime Flores and became military commander of the whole eastern zone of El Salvador. He was a rare thing: "pure, one-hundred-percent soldier, a natural leader, a born military man."[113] Monterrosa did not want wholesale bloodshed, but he wanted to win the war at any costs. He tried to be more relatable and less arrogant to the local population in the way he presented his military. When he first executed massacres he didn't think much of it because it was part of his military training and because it was tactically approved by the High Command, but he didn't consider whether it would become a political problem. He was accused of responsibility for what happened at El Mozote, though he denied it. Monterrosa later began to date a Salvadoran woman who worked in the press corps, for an American television network. Monterrosa's girlfriend let her co-worker know that something had gone wrong at El Mozote, though she did not go into detail. But people knew that he had lost radio contact with his men and that it was unfortunate and something that later brought regrettable consequences. Although he says he lost contact with his men, the guerrillas did not believe it and said it was well known to everyone that he had ordered the massacre. In an interview with James LeMoyne, however, he stated that he did in fact order his men to "clean out" El Mozote.[114]

Interim government and continued violence: 1982–1984

Peace offer and rejection

In 1982, the FMLN began calling for a peace settlement that would establish a "government of broad participation". The Reagan administration said the FMLN wanted to create a Communist dictatorship.[115] Elections were interrupted with right-wing paramilitary attacks and FMLN-suggested boycotts. El Salvador's National Federation of Lawyers, which represented all of the country's bar associations, refused to participate in drafting the 1982 electoral law. The lawyers said that the elections couldn't possibly be free and fair during a state of siege that suspended all basic rights and freedoms.

FMLN steps up campaign

Attacks against military and economic targets by the FMLN began to escalate. The FMLN attacked the Ilopango Air Force Base in San Salvador, destroying six of the Air Force's 14 Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopters, five of its 18 Dassault Ouragan aircraft and three C-47s.[116] Between February and April, a total of 439 acts of sabotage were reported.[117] The number of acts of sabotage involving explosives or arson rose to 782 between January and September.[118] The United States Embassy estimated the damage to the economic infrastructure at US$98 million.[119] FMLN also carried out large-scale operations in the capital city and temporarily occupied urban centres in the country's interior. According to some reports, the number of rebels ranged between 4,000 and 5,000; other sources put the number at between 6,000 and 9,000.[120]

Interim government

Pursuant to measures implemented by the JRG junta on 18 October 1979, elections for an interim government were held on 29 April 1982. The Legislative Assembly voted on three candidates nominated by the armed forces; Álvaro Alfredo Magaña Borja was elected by 36 votes to 17, ahead of the Party of National Conciliation and the hard right Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) candidates. Roberto D'Aubuisson accused Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez Avendaño of imposing on the Assembly "his personal decision to put Álvaro Alfredo Magaña Borja in the presidency" in spite of a "categorical no" from the ARENA deputies. Magana was sworn into office on 2 May.

Decree No. 6 of the National Assembly suspended phase III of the implementation of the agrarian reform, and was itself later amended. The Apaneca Pact was signed on 3 August 1982, establishing a Government of National Unity, whose objectives were peace, democratization, human rights, economic recovery, security and a strengthened international position. An attempt was made to form a transitional government that would establish a democratic system. Lack of agreement among the forces that made up the government and the pressures of the armed conflict prevented any substantive[clarification needed] changes from being made during Magaña's presidency.[121]

More atrocities by the government

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reported that, on 24 May 1982, a clandestine cemetery containing the corpses of 150 disappeared persons was discovered near Puerta del Diablo, Panchimalco, approximately twelve kilometers from San Salvador.[122] On 10 June 1982, almost 4,000 Salvadoran troops carried out a "cleanup" operation in the rebel-controlled Chalatenango province. Over 600 civilians were reportedly massacred during the Army sweep. The Salvadoran field commander acknowledged that an unknown number of civilian rebel sympathizers or "masas" were killed, while declaring the operation a success.[123] Nineteen days later, the Army massacred 27 unarmed civilians during house raids in a San Salvador neighborhood. The women were raped and murdered. Everyone was dragged from their homes into the street and then executed. "The operation was a success," said the Salvadoran Defense Ministry communique. "This action was a result of training and professionalization of our officers and soldiers."[124]

During 1982 and 1983, government forces killed approximately 8,000 civilians a year.[50]: 3 Although the figure is substantially less than the figures reported by human rights groups in 1980 and 1981, targeted executions as well as indiscriminate killings nonetheless remained an integral policy of the army and internal security forces, part of what Professor William Stanley described as a "strategy of mass murder" designed to terrorize the civilian population as well as opponents of the government.[50]: 225 General Adolfo Blandón, the Salvadoran armed forces chief of staff during much of the 1980s, has stated, "Before 1983, we never took prisoners of war."[125]

Government murder of human rights and labor union leaders

In March 1983, Marianella García Villas, president of the non-governmental Human Rights Commission of El Salvador, was captured by army troops on the Guazapa volcano, and later tortured to death. Garcia Villas had been on Guazapa collecting evidence about the possible army use of white phosphorus munitions.

In April 1983, Melida Anaya Montes, a leader of the Popular Forces for Liberation (FPL) "Farabundo Martí", a communist party-affiliated militia, was murdered in Managua, Nicaragua. Salvador Cayetano Carpio, her superior in the FPL, was allegedly implicated in her murder. He committed suicide in Managua shortly after Anaya Montes' murder. Their deaths influenced the course within the FMLN of the FPL's Prolonged Popular War strategy.[citation needed]

On 7 February 1984, nine labor union leaders, including all seven top officials of one major labor federation, were arrested by the Salvadoran National Police and sent to be tried by a military court. The arrests were part of Duarte's moves to crack down on labor unions after more than 80 trade unionists were detained in a raid by the National Police. The police confiscated the union's files and took videotape mugshots of each union member.

During a 15-day interrogation, the nine labor leaders were beaten during late-night questioning and were told to confess to being guerrillas. They were then forced to sign a written confession while blindfolded. They were never charged with being guerrillas but the official police statement said they were accused of planning to "present demands to management for higher wages and benefits and promoting strikes, which destabilize the economy." A U.S. official said the embassy had "followed the arrests closely and was satisfied that the correct procedures were followed."[126]

Duarte presidency: 1984–1989

Fixed elections and lack of accountability

In 1984 elections, Christian Democrat José Napoleón Duarte won the presidency (with 54 percent of the votes) against Army Major Roberto d'Aubuisson of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA). The elections were held under military rule amidst high levels of repression and violence, however, and candidates to the left of Duarte's brand of Christian Democrats were excluded from participating.[127] Fearful of a d'Aubuisson presidency for public relations purposes, the CIA financed Duarte's campaign with some two million dollars.[128] $10 million were put into the election as a whole, by the CIA, for electoral technology, administration and international observers.[129]

After Duarte's victory, human rights abuses at the hands of the army and security forces continued, but declined due to modifications made to the security structures. The policies of the Duarte government attempted to make the country's three security forces more accountable to the government by placing them under the direct supervision of a Vice Minister of Defense, but all three forces continued to be commanded individually by regular army officers, which, given the command structure within the government, served to effectively nullify any of the accountability provisions.[130][131] The Duarte government also failed to decommission personnel within the security structures that had been involved in gross human rights abuses, instead simply dispersing them to posts in other regions of the country.[132]

Days of Tranquillity

Following a proposal from Nils Thedin to UNICEF, "Days of tranquillity" were brokered between Government and rebel forces, under the direction of UNICEF Executive Director James Grant. For three days in 1985, all hostilities ceased to allow for mass-immunisation of any child against polio, measles, diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough. The program was successful. More than half of El Salvador's 400,000 children were immunised from 2,000 immunisation centres by 20,000 health workers, and the program was repeated in subsequent years until the conclusion of the war. Similar programs have since been instituted in Uganda, Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Sudan.[133][134]

Army massacres continue

While reforms were being made to the security forces, the army continued to massacre unarmed civilians in the country side. An Americas Watch report noted that the Atlácatl Battalion killed 80 unarmed civilians in Cabanas in July 1984, and carried out another massacre one month later, killing 50 displaced people in the Chalatenango province.[135] The women were raped and then everyone was systematically executed.[136]

Through 1984 and 1985, the Salvadoran Armed Forces enacted a series of "civic-action" programs in Chalatenango province, consisting of the establishment of "citizen defense committees" to guard plantations and businesses against attacks by insurgents and the establishment of a number of free-fire zones. These measures were implemented under former Cabanas commander, Lieutenant Colonel Sigifredo Ochoa Perez, who had previously been exiled to the US Army War College for mutiny.[137] By January 1985 Ochoa's forces had established 12 free-fire zones in Chalatenango in which any inhabitants unidentified by the army were deemed to be insurgents. Ochoa stated in an interview that areas within the free fire zone were susceptible to indiscriminate bombings by the Salvadoran Air Force. Ochoa's forces were implicated in a massacre of about 40 civilians in an Army sweep through one of the free fire zones in August 1985. Ochoa refused to permit the Red Cross to enter these areas to deliver humanitarian aid to the victims.[138] Ochoa's forces reportedly uprooted some 1,400 civilian rebel supporters with mortar fire between September and November 1984.[139]

In its annual review of 1987, Amnesty International reported that "some of the most serious violations of human rights are found in Central America", particularly Guatemala and El Salvador, where "kidnappings and assassinations serve as systematic mechanisms of the government against opposition from the left".[140] On 26 October 1987, unknown gunmen shot and killed Herbert Ernesto Anaya, Director of El Salvador's nongovernmental Human Rights Commission. Anaya was in his car in his driveway with his wife and children at the time. Some human rights groups linked the increase of death squad-style killings and disappearances to the reactivation of the popular organizations, which had been decimated by mass state terror in the early 1980s.[141] Col. Renee Emilio Ponce, the Army operations chief, asserted that the guerrillas were "returning to their first phase of clandestine organization" in the city, "and mobilization of the masses".[142]

Peace talks

During the Central American Peace Accords negotiations in 1987, the FMLN demanded that all death squads be disbanded and the members be held accountable. In October 1987, the Salvadoran Assembly approved an amnesty for civil-war-related crimes. The Amnesty law required the release of all prisoners suspected of being guerrillas and guerrilla sympathizers. Pursuant to these laws, 400 political prisoners were released. Insurgents were given a period of fifteen days to turn themselves over to the security forces in exchange for amnesty.[143] Despite amnesty being granted to guerillas and political prisoners, amnesty was also granted to members of the army, security forces and paramilitary who were involved in human rights abuses.[144]

Army death squads continue

In October 1988, Amnesty International reported that death squads had abducted, tortured, and killed, hundreds of suspected dissidents in the preceding eighteen months. Most of the victims were trade unionists and members of cooperatives, human rights workers, members of the judiciary involved in efforts to establish criminal responsibility for human rights violations, returned refugees and displaced persons, and released political prisoners.[145]

The squads comprised intelligence sections of the Armed Forces and the security services. They customarily wore plain clothes and made use of trucks or vans with tinted windows and without license plates. They were "chillingly efficient", said the report. Victims were sometimes shot from passing cars, in the daytime and in front of eyewitnesses. At other times, victims were kidnapped from their homes or on the streets and their bodies found dumped far from the scene. Others were forcefully "disappeared." Victims were "customarily found mutilated, decapitated, dismembered, strangled or showing marks of torture or rape." The death squad style was "to operate in secret but to leave mutilated bodies of victims as a means of terrifying the population."[145]

FMLN offensive of 1989 and retaliation

Outraged by the results of the 1988 fixed elections and the military's use of terror tactics and voter intimidation, the FMLN launched a major offensive known as the "final offensive of 1989" with the aim of unseating the government of President Alfredo Cristiani on 11 November 1989. This offensive brought the epicenter of fighting into the wealthy suburbs of San Salvador for essentially the first time in the history of the conflict, as the FMLN began a campaign of selective assassinations against political and military officials, civil officials, and upper-class private citizens.[146]

The government retaliated with a renewed campaign of repression, primarily against activists in the democratic sector.[146] The non-governmental Salvadoran Human Rights Commission (CDHES) counted 2,868 killings by the armed forces between May 1989 and May 1990.[147] In addition, the CDHES stated that government paramilitary organizations illegally detained 1,916 persons and disappeared 250 during the same period.[148]

On 13 February, the Atlácatl Battalion attacked a guerrilla field hospital and killed at least 10 people, including five patients, a physician and a nurse. Two of the female victims showed signs that they had been raped before they were executed.

US message

Nearly two weeks earlier, US Vice President Dan Quayle on a visit to San Salvador told army leaders that human rights abuses committed by the military had to stop. Sources associated with the military said afterword that Quayle's warning was dismissed as propaganda for American consumption aimed at the US Congress and public.[149] At the same time, critics argued US military advisors were possibly sending a different message to the Salvadoran military: "Do what you need to do to stop the commies, just don't get caught".[150] A former US intelligence officer suggested the death squads needed to leave less visual evidence, that they should stop dumping bodies on the side of the road because "they have an ocean and they ought to use it".[151] The School of the Americas, founded by the United States, trained many members of the Salvadoran military, including Roberto D'Aubuisson, organizer of death squads, and military officers linked to the murder of Jesuit priests.[152]

In a 29 November 1989 press conference, Secretary of State James A. Baker III said he believed President Cristiani was in control of the army and defended the government's crackdown on opponents as "absolutely appropriate".[153] The US Trade Representative told Human Rights Watch that the government's repression of trade unionists was justified on the grounds that they were guerrilla supporters.[154][155]

Government terrorism in San Salvador

In San Salvador on 1 October 1989, eight people were killed and 35 others were injured when a death squad bombed the headquarters of the leftist labor confederation, the National Trade Union Federation of Salvadoran Workers (UNTS).[156]

Earlier the same day, another bomb exploded outside the headquarters of a victims' advocacy group, the Committee of Mothers and Family Members of Political Prisoners, Disappeared and Assassinated of El Salvador, injuring four others.[157]

Death squads attack the Catholic Church

As early as the 1980s, the University of Central America fell under attack from the army and death squads. On 16 November 1989, five days after the beginning of the FMLN offensive, uniformed soldiers of the Atlácatl Battalion entered the campus of the University of Central America in the middle of the night and executed six Jesuit priests—Ignacio Ellacuría, Segundo Montes, Ignacio Martín-Baró, Joaquín López y López, Juan Ramón Moreno, and Amando López—and their housekeepers (a mother and daughter, Elba Ramos and Celia Marisela Ramos). The priests were dragged from their beds on the campus, machine gunned to death and their corpses mutilated. The mother and daughter were found shot to death in the bed they shared.[158] The Atlácatl Battalion was reportedly under the tutelage of U.S. special forces just 48 hours before the killings.[159] One day later, six men and one youth were slaughtered by government soldiers in the capital, San Salvador. According to relatives and neighbors who witnessed the killings, the six men were lined up against a masonry wall and shot to death. The seventh youth who happened to be walking by at the time was also executed.[160]

The Salvadoran government then began a campaign to dismantle a liberal Catholic Church network that the army said were "front organizations" supporting the guerrillas. Church offices were raided and workers were arrested and expelled. Targets included priests, lay workers and foreign employees of humanitarian agencies, providing social services to the poor: food programs, healthcare, relief for the displaced.[161] One Church volunteer, who was a U.S. citizen, said she was blindfolded, tortured and interrogated in Treasury Police headquarters in San Salvador while a U.S. vice consul "having coffee with the colonel in charge" did nothing to intervene.[162]

Pressures to end stalemate

The murder of the six Jesuit priests and the November 1989 "final offensive" by the FMLN in San Salvador, however, were key turning points that increased international pressure and domestic pressure from war-weary constituents that alternatives to the military stalemate needed to be found. International support for the FMLN was declining with the end of the Cold War just as international support for the Salvadoran armed forces was weakening as the Reagan administration gave way to the less ideological Bush administration, and the end of the Cold War lessened the anti-Communist concerns about a potential domino effect in Central America.[163]

By the late 1980s, 75 percent of the population lived in poverty.[40] The living standards of most Salvadorans declined by 30 percent since 1983. Unemployment or underemployment increased to 50 percent.[164] Most people, moreover, still didn't have access to clean water or healthcare. The armed forces were feared, inflation rose almost 40 percent, capital flight reached an estimated $1 billion, and the economic elite avoided paying taxes.[165] Despite nearly $3 billion in American economic assistance, per capita income declined by one third.[40]

American aid was distributed to urban businesses although the impoverished majority received almost none of it.[165] The concentration of wealth was even higher than before the U.S.-administered land reform program. The agrarian law generated windfall profits for the economic elite and buried the cooperatives in debts that left them incapable of competing in the capital markets. The oligarchs often took back the land from bankrupt peasants who couldn't obtain the credit necessary to pay for seeds and fertilizer.[166] Although, "few of the poor would dream of seeking legal redress against a landlord because virtually no judge would favor a poor man."[165] By 1989, 1 percent of the landowners owned 41 percent of the tillable land, while 60 percent of the rural population owned 0 percent.[40]

Death squads and peace accords: 1990–1992

After 10 years of war, more than one million people had been displaced out of a population of 5,389,000. 40 percent of the homes of newly displaced people were completely destroyed and another 25 percent were in need of major repairs.[167] Death squad activities further escalated in 1990, despite a UN Agreement on Human Rights signed 26 July by the Cristiani government and the FMLN.[168] In June 1990, U.S. President George Bush announced an "Enterprise for the Americas Initiative" to improve the investment climate by creating "a hemisphere-wide free trade zone."[169]

President Bush authorized the release of $42.5 million in military aid to the Salvadoran armed forces on 16 January 1991.[170] In late January, the Usulután offices of the Democratic Convergence, a coalition of left-of-center parties, were attacked with grenades. On 21 February, a candidate for the Democratic National Unity (UDN) party and his pregnant wife were assassinated after ignoring death squad threats to leave the country or die. On the last day of the campaign, another UDN candidate was shot in her eye when Arena party gunmen opened fire on campaign activists putting up posters. Despite fraudulent elections orchestrated by Arena through voter intimidation, sabotage of polling stations by the Arena-dominated Central Elections Council and the disappearing of tens of thousands of names from the voting lists, the official U.S. observation team declared them "free and fair."[171]

Death squad killings and disappearances remained steady throughout 1991 as well as torture, false imprisonment, and attacks on civilians by the Army and security forces. Opposition politicians, members of church and grassroots organizations representing peasants, women and repatriated refugees suffered constant death threats, arrests, surveillance and break-ins all year. The war intensified in mid-1991, as both the army and the FMLN attempted to gain the advantage in the United Nations-brokered peace talks prior to a cease-fire. Indiscriminate attacks and executions by the armed forces increased as a result.[172] Eventually, by April 1991, negotiations resumed, resulting in a truce that successfully concluded in January 1992, bringing about the war's end.[citation needed] On 16 January 1992, the Chapultepec Peace Accords were signed in Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City, to bring peace to El Salvador.[173] The Armed Forces were regulated, a civilian police force was established, the FMLN metamorphosed from a guerrilla army to a political party, and an amnesty law was legislated in 1993.[174]

Aftermath

The peace process set up under the Chapultepec Accords was monitored by the United Nations from 1991 until June 1997 when it closed its special monitoring mission in El Salvador.

In 1996, U.S. authorities acknowledged for the first time that U.S. military personnel had died in combat during the civil war. Officially, American advisers were prohibited from participating in combat operations, but they carried weapons, and accompanied Salvadoran army soldiers in the field and were subsequently targeted by rebels. 21 Americans were killed in action during the civil war and more than 5,000 served.[2]

Truth Commission

At war's end, the Commission on the Truth for El Salvador registered more than 22,000 complaints of political violence in El Salvador, dating between January 1980 and July 1991, 60 percent about summary killing, 25 percent about kidnapping, and 20 percent about torture. These complaints attributed almost 85 percent of the violence to the Salvadoran Army and security forces alone. The Salvadoran Armed Forces, which were massively supported by the United States (4.6 billion dollars in 2009),[175] were accused in 60 percent of the complaints, the security forces (i.e. the National Guard, Treasury Police and the National Police) in 25 percent, military escorts and civil defense units in 20 percent of complaints, the death squads in approximately 10 percent, and the FMLN in 5 percent.[175] The Truth Commission could collect only a significant sample of the full number of potential complaints, having had only three months to collect it.[176] The report concluded that more than 70,000 people were killed, many in the course of gross violation of their human rights. More than 25 per cent of the populace was displaced as refugees before the U.N. peace treaty in 1992.[177][178]

The statistics presented in the Truth Commission's report are consistent with both previous and retrospective assessments by the international community and human rights monitors, which documented that the majority of the violence and repression in El Salvador was attributable to government agencies, primarily the National Guard and the Salvadoran Army.[179][180][181] A 1984 Amnesty International report stated that many of the 40,000 people killed in the preceding five years had been murdered by government forces, who openly dumped their mutilated corpses in an apparent effort to terrorize the population.[182][183]

The government mostly killed peasants, but many other opponents suspected of sympathy with the guerrillas—clergy (men and women), church lay workers, political activists, journalists, labor unionists (leaders, rank-and-file), medical workers, liberal students and teachers, and human-rights monitors were also killed.[184] The killings were carried out by the security forces, the Army, the National Guard, and the Treasury Police;[1]: 308 [185] but it was the paramilitary death squads that gave the Government plausible deniability of, and accountability for the killings. Typically, a death squad dressed in civilian clothes and traveled in anonymous vehicles (dark windows, blank license plates). The deaths squads tactics included publishing future-victim death lists, delivering coffins to said future victims, and sending the target-person an invitation to his/her own funeral.[186][187] Cynthia Arnson, a Latin American-affairs writer for Human Rights Watch, says: the objective of death-squad-terror seemed not only to eliminate opponents, but also, through torture and the gruesome disfigurement of bodies, to terrorize the population.[188] In the mid-1980s, state terror against civilians became open with indiscriminate bombing from military airplanes, planted mines, and the harassment of national and international medical personnel. Author George Lopez writes that "although death rates attributable to the death squads have declined in El Salvador since 1983, non-combatant victims of the civil war have increased dramatically".[189]

Though the violations of the FMLN accounted for five percent or less of those documented by the Truth Commission, the FMLN continuously violated the human rights of many Salvadorans and other individuals identified as right-wing supporters, military targets, pro-government politicians, intellectuals, public officials, and judges. These violations included kidnapping, bombings, rape, and killing.[176]

Military reform

In accordance with the peace agreements, the constitution was amended to prohibit the military from playing an internal security role except under extraordinary circumstances. During the period of fulfilling of the peace agreements, the Minister of Defense was General Humberto Corado Figueroa. Demobilization of Salvadoran military forces generally proceeded on schedule throughout the process. The Treasury Police and National Guard were abolished, and military intelligence functions were transferred to civilian control. By 1993—nine months ahead of schedule—the military had cut personnel from a wartime high of 63,000 to the level of 32,000 required by the peace accords. By 1999, ESAF's strength stood at less than 15,000, including uniformed and non-uniformed personnel, consisting of personnel in the army, navy, and air force. A purge of military officers accused of human rights abuses and corruption was completed in 1993 in compliance with the Ad Hoc Committee's recommendations.[citation needed]

National Civil Police

The new civilian police force, created to replace the discredited public security forces, deployed its first officers in March 1993, and was present throughout the country by the end of 1994. In 1999, the PNC had over 18,000 officers. The PNC faced many challenges in building a completely new police force. With common crime rising dramatically since the end of the war, over 500 PNC officers had been killed in the line of duty by late 1998. PNC officers also have arrested a number of their own in connection with various high-profile crimes, and a "purification" process to weed out unfit personnel from throughout the force was undertaken in late 2000.[190]

Human Rights Commission of El Salvador

On 26 October 1987, Herbert Ernesto Anaya, head of the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador (CDHES), was assassinated. His killing provoked four days' of political protest—during which his remains were displayed before the U.S. embassy and then before the Salvadoran armed forces headquarters. The National Union of Salvadoran Workers said: "Those who bear sole responsibility for this crime are José Napoleón Duarte, the U.S. embassy...and the high command of the armed forces". In its report the Commission on the Truth for El Salvador, established as part of the El Salvador peace agreement, stated that it could not establish for sure whether the death squads, the Salvadoran Army or the FMLN was responsible for Anaya's death.

Moreover, the FMLN and the Revolutionary Democratic Front (FDR) also protested Mr. Anaya's assassination by suspending negotiations with the Duarte government on 29 October 1987. The same day, Reni Roldán resigned from the Commission of National Reconciliation, saying: "The murder of Anaya, the disappearance of university labor leader Salvador Ubau, and other events do not seem to be isolated incidents. They are all part of an institutionalized pattern of conduct". Mr. Anaya's assassination evoked international indignation: the West German government, the West German Social Democratic Party, and the French government asked President Duarte to clarify the circumstances of the crime. United Nations Secretary General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Americas Watch, Amnesty International, and other organizations protested against the assassination of the leader of the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador.[191]

Post-war international litigation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

Groups seeking investigation or retribution for actions during the war have sought the involvement of other foreign courts. In 2008 the Spanish Association for Human Rights and a California organization called the Center for Justice and Accountability jointly filed a lawsuit in Spain against former President Cristiani and former defense minister Larios in the matter of the 1989 slaying of several Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter. The lawsuit accused Cristiani of a cover-up of the killings and Larios of participating in the meeting where the order to kill them was given; the groups asked the Spanish court to intervene on the principle of universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity.[192]

Long after the war, in a U.S. federal court, in the case of Ford vs. García the families of the murdered Maryknoll nuns sued the two Salvadoran generals believed responsible for the killings, but lost; the jury found Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, ex-National Guard Leader and Duarte's defense minister, and Gen. José Guillermo García—defense minister from 1979 to 1984, not responsible for the killings; the families appealed and lost, and, in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear their final appeal. A second case, against the same generals, succeeded in the same Federal Court; the three plaintiffs in Romagoza vs. García won a judgment exceeding US$54 million compensation for having been tortured by the military during El Salvador's Civil War.

The day after losing a court appeal in October 2009, the two generals were put into deportation proceedings by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), at the urging of U.S. Senators Richard Durbin (Democrat) and Tom Coburn (Republican), according to the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA). Those deportation proceedings had been stalled by May 2010.

The Spanish Judge Velasco who issued indictments and arrest warrants for 20 former members of the Salvadoran military, charged with murder, Crimes Against Humanity and Terrorism requested that U.S. agencies declassify documents related to the killings of the Jesuits, their housekeeper and her daughter but were denied access.[193]

"The agencies in charge of making the information public have identified 3,000 other documents that remain secret and are not available; the reasoning given is that privacy is needed to protect sources and methods. Many of the documents, from the CIA and the Defense Department, are not available..."[194]

The Cold War with the Soviet Union and other communist nations at least partially explains the backdrop against which the U.S. government aided various pro-government Salvadoran groups and opposed the FMLN. The U.S. State Department reported on intelligence that the FMLN was receiving clandestine guidance and arms from the Cuban, Nicaraguan, and Soviet governments.[195] While this White Paper on El Salvador later received criticism from some academics and journalists, it has also been largely substantiated based on the evidence available at the time.[196] The closure of the Cold War between 1989 and 1991 reduced the incentive for ongoing U.S. involvement and invited broad international support for the negotiation process that would lead to the 1992 peace accords.[197]

The political and economic divisions at play in El Salvador during the civil war were complex, which is often overlooked by scholars and analysts eager to vindicate one side or the other. More research is needed, for example, to shed light on Salvadorans that resisted as political independents or as part of pro-democracy coalitions.[198] After a 2012 historians seminar at the University of El Salvador commemorating the 20th anniversary of the peace accords, Michael Allison concluded:

"Most postwar discourse has been driven by elites who participated in the conflict either on the part of the guerrillas or the government. It's not that these individuals' perspectives are wrong; it is just healthier if they are challenged or supplemented by outside views."[198]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Three dates that are often cited as the start date of the Salvadoran Civil War: 15 October 1979 when the 1979 Salvadoran coup d'état occurred,[5]: 262 [6]: 155 [7]: 206 [8]: 4 [9]: 40 sometime during 1980,[10]: 221 & 223 [11]: 688 [12]: 781 [13]: 211 and 10 January 1981 when the final offensive of 1981 began.[14]: 242 [15]: 31

- ^ Armed with M16, IMI Galil, and G3 assault rifles; Uzi submachine guns; heavy weapons including artillery and missiles of North American manufacturing; and helicopters and fighter jets

- ^ Armed with: assault rifle AK-47 and M16; machine guns RPK and PKM; and handmade explosives.

References

- ^ a b c Michael McClintock (1985). The American connection: state terror and popular resistance in El Salvador. London: Zed Books. p. 388. ISBN 0862322405.

- ^ a b Graham, Bradley (6 May 1996). "Public Honors for Secret Combat". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ El Salvador, In Depth, Negotiating a settlement to the conflict. Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University.

US government increased the security support to prevent a similar thing to happen in El Salvador. This was, not least, demonstrated in the delivery of security aid to El Salvador

- ^ a b c Oñate, Andrea (15 April 2011). "The Red Affair: FMLN–Cuban relations during the Salvadoran Civil War, 1981–92". Cold War History. 11 (2): 133–154. doi:10.1080/14682745.2010.545566. S2CID 153325313. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ McClintock, Michael (1985). The American Connection: State Terror and Popular Resistance in El Salvador. Vol. 1. London, United Kingdom: Zed Books. ISBN 9780862322403. OCLC 1145770950. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Torture in the Eighties: An Amnesty International Report. London, United Kingdom: Amnesty International. 1984. pp. 155–158. ISBN 9780939994069. OCLC 1036878685. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ Acosta, Pablo; Baez, Javier E.; Caruso, Germán & Carcach, Carlos (2023). "The Scars of Civil War: The Long-Term Welfare Effects of the Salvadoran Armed Conflict" (PDF). Economía. 22 (1). LSE Press: 203–217. ISSN 1529-7470. JSTOR 27302241. OCLC 10243911663. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Ram, Susan (1983). "El Salvador: Perspectives on a Revolutionary Civil War". Social Scientist. 11 (8). Social Scientist: 3–38. doi:10.2307/3517048. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3517048. OCLC 5546270152.

- ^ Doucette, John W. (1999). U.S. Air Force lessons in Counterinsurgency: Exposing Voids in Doctrinal Guidance. Air University Press. pp. 39–60. JSTOR resrep13838. OCLC 831719036.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez, Luis Guillermo & Quijano de Batres, Ana Elia, eds. (2009). Historia 2 El Salvador [History 2 El Salvador] (PDF). Historia El Salvador (in Spanish). El Salvador: Ministry of Education. ISBN 9789992363683. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Hoover Green, Amelia (2017). "Armed Group Institutions and Combatant Socialization: Evidence from El Salvador". Journal of Peace Research. 54 (5). Sage Publishing: 687–700. doi:10.1177/0022343317715300. ISSN 0022-3433. JSTOR 48590496. OCLC 7126356262.

- ^ Hoover Green, Amelia & Ball, Patrick (2019). "Civilian Killings and Disappearances During Civil War in El Salvador (1980–1992)" (PDF). Demographic Research. 41 (27). Max Planck Society: 781–814. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.27. ISSN 1435-9871. JSTOR 26850667. OCLC 8512899425. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Seligson, Mitchell A. & McElhinny, Vincent (1996). "Low Intensity Warfare, High-Intensity Death: The Demographic Impact of the Wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 21 (42). Taylor & Francis: 211–241. ISSN 0826-3663. JSTOR 41799994. OCLC 9983726023. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Héctor; Ching, Erik K. & Lara Martínez, Rafael A. (2007). Remembering a Massacre in El Salvador: The Insurrection of 1932, Roque Dalton, and the Politics of Historical Memory. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826336040. OCLC 122424174. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Jones, Seth G.; Oliker, Olga; Chalk, Peter; Fair, C. Christine; Lal, Rollie & Dobbins, James (2006). Securing Tyrants or Fostering Reform? U.S. Internal Security Assistance to Repressive and Transitioning Regimes (1 ed.). Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation. pp. 23–48. doi:10.7249/mg550osi. ISBN 9780833042620. JSTOR 10.7249/mg550osi. OCLC 184843895.

- ^ a b c Michael W. Doyle, Ian Johnstone & Robert Cameron Orr (1997). Keeping the Peace: Multidimensional UN Operations in Cambodia and El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 222. ISBN 978-0521588379.

- ^ a b María Eugenia Gallardo & José Roberto López (1986). Centroamérica. San José: IICA-FLACSO, p. 249. ISBN 978-9290391104.

- ^ "Dirección de Asuntos del Hemisferio Occidental: Información general – El Salvador". U.S. State Department. 18 November 2004. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014.

- ^ a b Andrews Bounds (2001). South America, Central America and The Caribbean 2002. El Salvador: History (10a ed.). London: Routledge. p. 384. ISBN 978-1857431216.

- ^ Charles Hobday (1986). Communist and Marxist parties of the world. New York: Longman, p. 323. ISBN 978-0582902640.

- ^ "El Salvador 30 años del FMLN". El Economista. 13 de octubre de 2010.

- ^ 2006 – Manuel Guedán – Carta del Director. Un Salvador violento celebra quince años de paz, article in Quorum. Journal of Latin American Thought, winter, number 016, University of Alcala, Madrid, Spain, pp. 6–11

- ^ a b c d Seligson, Mitchell A.; McElhinny, Vincent. Low Intensity Warfare, High Intensity Death: The Demographic Impact of the Wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua (PDF). University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Irvine, Reed and Joseph C. Goulden. "U.S. left's 'big lie' about El Salvador deaths." Human Events (9/15/90): 787.

- ^ Dictionary of Wars, by George Childs Kohn (Facts on File, 1999)

- ^ Britannica, 15th edition, 1992 printing

- ^ "United States General Accounting Office. Report to the Honorable Edward M Kennedy, US Senate. El Salvador. Military Assistance has helped counter but not overcome the insurgency" (PDF). April 1991. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Wood, Elizabeth (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Chapultepec Peace Agreement" (PDF). UCDP. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Report of the UN Truth Commission on El Salvador (Report). United Nations. 1 April 1993.

- ^ "'Removing the Veil': El Salvador Apologizes for State Violence on 20th Anniversary of Peace Accords". NACLA. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "El Salvador's Funes apologizes for civil war abuses". Reuters. 16 January 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Danner, Mark (1993). The Massacre at El Mozote. Vintage Books. pp. 9. ISBN 067975525X.

- ^ El Salvador, In Depth: Negotiating a settlement to the conflict. Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

While nothing of the aid delivered from the US in 1979 was earmarked for security purposes, the 1980 aid for security only summed US$6.2 million, close to two-thirds of the total aid in 1979.

- ^ "philly.com: The Philadelphia Inquirer Historical Archive (1860–1922)". Archived from the original on 18 February 2019 – via nl.newsbank.com.

- ^ Stokes, Doug (9 August 2006). "Countering the Soviet Threat? An Analysis of the Justifications for US Military Assistance to El Salvador, 1979–92". Cold War History. 3 (3): 79–102. doi:10.1080/14682740312331391628. S2CID 154097583. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Truth Commission: El Salvador". 1 July 1992. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Incostitucionalidad 44-2013/145-2013" (PDF) (in Spanish). Supreme Court of Justice of El Salvador. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ COHA (25 July 2016). "El Salvador's 1993 Amnesty Law Overturned: Implications for Colombia".

- ^ a b c d "Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America" By Walter Lafeber, 1993

- ^ Haggerty, Richard A. (1990). El Salvador: A Country Study. Headquarters, Department of The Army. p. 306.

- ^ "El Salvador en los años 1920–1932" (in Spanish). 8 January 2007. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ^ Armed Forces of El Salvador. "Revolución 1932" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ^ a b Little, Michael (1994). A war of information : the conflict between public and private U.S. foreign policy on El Salvador, 1979–1992. University Press of America. ISBN 9780819193117.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Robert; Vanden, Harry (September 1982). "Defining Terrorism in El Salvador: La Matanza". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 463: 106–118. doi:10.1177/0002716282463001009. S2CID 145461772.

- ^ Haggerty, Richard A. (November 1988). "Foreign Military Influence and Assistance". El Salvador: A Country Study (PDF). Federal Research Division Library of Congress. pp. 223–224.

- ^ Walter, Williams (1997). Militarization and Demilitarization in El Salvador's Transition to Democracy. p. 90.

- ^ Armstrong, Robert / Shenk, Janet. El Salvador: The Face of Revolution (Boston: South End Press, 1982), 163.

- ^ Whitfield, Teresa (1995). Paying the Price: Ignacio Ellacuría and the Murdered Jesuits of El Salvador. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 9781566392532.

- ^ a b c d Stanley, William (1996). The Protection Racket State: Elite Politics, Military Extortion, and Civil War in El Salvador. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1566393922. Stanley William, Professor at the University of New Mexico

- ^ Dunkerley, James (1982). The Long War: Dictatorship and Revolution in El Salvador. pp. 106–107.

- ^ Stanley, 2012, p. 120

- ^ a b Socorro Jurídico Cristiano

- ^ Library of Congress. Country Studies. El Salvador. Background to the Insurgency. [1]

- ^ Gettleman, Marvin (1987). El Salvador : Central America in the new Cold War. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0394555570.

- ^ Rabe, Stephen (2016). The killing zone : the United States wages Cold War in Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190216252.

- ^ Pastor, Robert (Winter 1984). "Continuity and Change in U.S. Foreign Policy: Carter and Reagan on El Salvador". Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 3 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1002/pam.4050030202.

- ^ McMahan, Jeff (1985). Reagan and the world : imperial policy in the new Cold War. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 085345678X.

- ^ a b Report of the UN Truth Commission on El Salvador. 1 April 1993. p. 27.

- ^ NACLA, Revolution Brews cited in McClintock 1985, p. 270

- ^ United States Embassy in San Salvador, cable 02296, 31 March 1980. The Washington Post, 31 March 1980.

- ^ National Security Archives, El Salvador: The Making of US Policy, 1977–1984, p. 34.

- ^ United States. Dept. of State. Bureau of Public Affairs (1985). Central America, US policy. Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State. ISBN 9780080309507.

- ^ Arneson, Cynthia (1993). Crossroads: Congress, the President, and Central America, 1976–1993. Penn State Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780271041285.

- ^ "El Salvador Accountability and Human Rights: the Report of the United Nations Commission on the Truth for El Salvador" Human Rights Watch, 10 August 1993

- ^ Wood, Elisabeth J. (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0521010504.

- ^ Wood, Elisabeth J. (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0521010504.

- ^ Wood, Elisabeth J. (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18, 19. ISBN 978-0521010504.