Sukkot

| Sukkot | |

|---|---|

A sukkah (plural: sukkot) in a kibbutz in Gush Etzion | |

| Official name | Hebrew: סוכות or סֻכּוֹת ("Booths, Tabernacles") |

| Observed by | |

| Type | Jewish, Samaritan |

| Significance | One of the three pilgrimage festivals shalosh regalim |

| Observances | Dwelling and eating festive meals in a sukkah; holding and carrying the four species; doing hakafot and praising God with hallel prayers in synagogues |

| Begins | 15th day of Tishrei |

| Ends | 21st day of Tishrei |

| Date | 15 Tishrei, 16 Tishrei, 17 Tishrei, 18 Tishrei, 19 Tishrei, 20 Tishrei, 21 Tishrei |

| 2023 date | Sunset, 29 September – nightfall, 6 October (7 October outside of Israel) |

| 2024 date | Sunset, 16 October – nightfall, 23 October (24 October outside of Israel)[1] |

| 2025 date | Sunset, 6 October – nightfall, 13 October (14 October outside of Israel) |

| 2026 date | Sunset, 25 September – nightfall, 2 October (3 October outside of Israel) |

| Related to | Shemini Atzeret, Simchat Torah |

Sukkot,[a] also known as the Feast of Tabernacles or Feast of Booths, is a Torah-commanded holiday celebrated for seven days, beginning on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei. It is one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals on which Israelites were commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. Biblically an autumn harvest festival and a commemoration of the Exodus from Egypt, Sukkot’s modern observance is characterized by festive meals in a sukkah, a temporary wood-covered hut.

The names used in the Torah are "Festival of Ingathering" (or "Harvest Festival", Hebrew: חַג הָאָסִיף, romanized: ḥag hāʾāsif)[2] and "Festival of Booths" (Hebrew: חג הסכות, romanized: Ḥag hasSukkōṯ).[3][2] This corresponds to the double significance of Sukkot. The one mentioned in the Book of Exodus is agricultural in nature—"Festival of Ingathering at the year's end" (Exodus 34:22)—and marks the end of the harvest time and thus of the agricultural year in the Land of Israel. The more elaborate religious significance from the Book of Leviticus is that of commemorating the Exodus and the dependence of the Israelites on the will of God (Leviticus 23:42–43).

As an extension of its harvest festival community roots, the idea of welcoming all guests and extending hospitality is intrinsic to the celebration. Actual and symbolic "guests" (Aramaic: ushpizin) are invited to participate by visiting the sukkah. Specifically, seven "forefathers" of the Jewish people are to be welcomed during the seven days of the festival, in this order: Day 1: Abraham; Day 2: Isaac; Day 3: Jacob; Day 4: Moses; Day 5: Aaron; Day 6: Joseph; Day 7: David.[4]

The holiday lasts seven days. The first day (and second day in the diaspora) is a Shabbat-like holiday when work is forbidden. This is followed by intermediate days called Chol HaMoed, during which certain work is permitted. The festival is closed with another Shabbat-like holiday called Shemini Atzeret (one day in the Land of Israel, two days in the diaspora, where the second day is called Simchat Torah).

The Hebrew word sukkoṯ is the plural of sukkah ('booth' or 'tabernacle') which is a walled structure covered with s'chach (plant material, such as overgrowth or palm leaves). A sukkah is the name of the temporary dwelling in which farmers would live during harvesting, reinforcing agricultural significance of the holiday introduced in the Book of Exodus. As stated in Leviticus, it is also reminiscent of the type of fragile dwellings in which the Israelites dwelled during their 40 years of travel in the desert after the Exodus from slavery in Egypt. Throughout the holiday, meals are eaten inside the sukkah and many people sleep there as well.

On each day of the holiday it is a mitzvah, or commandment, to 'dwell' in the sukkah and to perform a shaking ceremony with a lulav (a palm frond, then bound with myrtle and willow), and an etrog (the fruit of a citron tree) (collectively known as the four species). The fragile shelter, the 'now-three-item' lulav, the etrog, the revived Simchat Beit HaShoeivah celebration's focus on water and rainfall and the holiday's harvest festival roots draw attention to people's dependence on the natural environment.

Origins

Sukkot shares similarities with older Canaanite new-year/harvest festivals, which included a seven-day celebration with sacrifices reminiscent of those in Num. 29:13–38 and "dwellings of branches," as well as processions with branches. The earliest references in the Bible (Ex. 23:16 & Ex. 34:22) make no mention of Sukkot, instead referring to it as "the festival of ingathering (hag ha'asif) at the end of the year, when you gather in the results of your work from the field," suggesting an agricultural origin. (The Hebrew term asif is also mentioned in the Gezer calendar as a two-month period in the autumn.)

The booths aspect of the festival may come from the shelters that were built in the fields by those involved in the harvesting process. Alternatively, it may come from the booths which pilgrims would stay in when they came in for the festivities at the cultic sanctuaries.[5][6][7][8][9] Finally, Lev. 23:40 talks about the taking of various branches (and a fruit), this too is characteristic of ancient agricultural festivals, which frequently included processions with branches.[7]: 17

Later, the festival was historicized by symbolic connection with the desert sojourn of exodus (Lev. 23:42–43).[6] The narratives of the exodus trek do not describe the Israelites building booths,[10][7]: 18 but they indicate that most of the trek was spent encamped at oases rather than traveling, and "sukkot" roofed with palm branches were a popular and convenient form of housing at such Sinai desert oases.[11]

Laws and customs

Sukkot is a seven-day festival. Inside the Land of Israel, the first day is celebrated as a full festival with special prayer services and holiday meals. Outside the Land of Israel, the first two days are celebrated as full festivals. The seventh day of Sukkot is called Hoshana Rabbah ("Great Hoshana", referring to the tradition that worshippers in the synagogue walk around the perimeter of the sanctuary during morning services) and has a special observance of its own. The intermediate days are known as Chol HaMoed ("festival weekdays"). According to Halakha, some types of work are forbidden during Chol HaMoed.[12] In Israel many businesses are closed during this time.[13]

Throughout the week of Sukkot, meals are eaten in the sukkah. If a brit milah (circumcision ceremony) or Bar Mitzvah rises during Sukkot, the seudat mitzvah (obligatory festive meal) is served in the sukkah. Similarly, the father of a newborn boy greets guests to his Friday-night Shalom Zachar in the sukkah. Males sleep in the sukkah, provided the weather is tolerable. If it rains, the requirement of eating and sleeping in the sukkah is waived, except for eating there on the first night where every effort needs to be made to at least say kiddush (the sanctification prayer on wine) and eat an egg-sized piece of bread before going inside the house to finish the meal if the rain does not stop. Every day except the Sabbath, a blessing is recited over the Lulav and the Etrog.[14] Keeping of Sukkot is detailed in the Hebrew Bible (Nehemiah 8:13–18, Zechariah 14:16–19 and Leviticus 23:34–44); the Mishnah (Sukkah 1:1–5:8); the Tosefta (Sukkah 1:1–4:28); and the Jerusalem Talmud (Sukkah 1a–) and Babylonian Talmud (Sukkah 2a–56b).

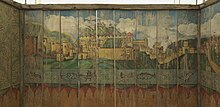

Sukkah

The sukkah walls can be constructed of any material that blocks wind (wood, canvas, aluminum siding, sheets). The walls can be free-standing or include the sides of a building or porch. There must be at least two and a partial wall.[15] The roof must be of organic material, known as s'chach, such as leafy tree overgrowth, schach mats or palm fronds – plant material that is no longer connected with the earth.[16] It is customary to decorate the interior of the sukkah with hanging decorations of the four species[17] as well as with attractive artwork.[18]

Prayers

Prayers during Sukkot include the reading of the Torah every day, reciting the Mussaf (additional) service after morning prayers, reciting Hallel, and adding special additions to the Amidah and Grace after Meals. In addition, the service includes rituals involving the Four Species. The lulav and etrog are not used on the Sabbath.[19]

On the Festival days, as well as the Sabbath of Chol Hamoed, some communities recite piyyutim.[20]

Hoshanot

On each day of the festival, worshippers walk around the synagogue carrying the Four Species while reciting special prayers known as Hoshanot.[19]: 852 This takes place either after the morning's Torah reading or at the end of Mussaf. This ceremony commemorates the willow ceremony at the Temple in Jerusalem, in which willow branches were piled beside the altar with worshippers parading around the altar reciting prayers.[21]

Ushpizin and ushpizata

A custom originating with Lurianic Kabbalah is to recite the ushpizin prayer to "invite" one of seven "exalted guests" into the sukkah.[22] These ushpizin (Aramaic אושפיזין 'guests'), represent the "seven shepherds of Israel": Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph and David, each of whom correlate with one of the seven lower Sephirot (this is why Joseph, associated with Yesod, follows Moses and Aaron, associated with Netzach and Hod respectively, even though he precedes them in the narrative). According to tradition, each night a different guest enters the sukkah followed by the other six. Each of the ushpizin has a unique lesson to teach that parallels the spiritual focus of the day on which they visit, based on the Sephirah associated with that character.[23]

Some streams of Reconstructionist Judaism also recognize a set of seven female shepherds of Israel, called variously Ushpizot (using modern Hebrew feminine pluralization), or Ushpizata (in reconstructed Aramaic). Several lists of seven have been proposed. The Ushpizata are sometimes coidentified with the seven prophetesses of Judaism: Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Hulda, and Esther.[24] Some lists seek to relate each female leader to one of the Sephirot, to parallel their male counterparts of the evening. One such list (in the order they would be invoked, each evening) is: Ruth, Sarah, Rebecca, Miriam, Deborah, Tamar, and Rachel.[25]

Chol HaMoed intermediate days

The second through seventh days of Sukkot (third through seventh days outside the Land of Israel) are called Chol HaMoed (חול המועד – lit. "festival weekdays"). These days are considered by halakha to be more than regular weekdays but less than festival days. In practice, this means that all activities that are needed for the holiday—such as buying and preparing food, cleaning the house in honor of the holiday, or traveling to visit other people's sukkot or on family outings—are permitted by Jewish law. Activities that will interfere with relaxation and enjoyment of the holiday—such as laundering, mending clothes, engaging in labor-intensive activities—are not permitted.[26][27]

Religious Jews often treat Chol HaMoed as a vacation period, eating nicer than usual meals in their sukkah, entertaining guests, visiting other families in their sukkot, and taking family outings. Many synagogues and Jewish centers also offer events and meals in their sukkot during this time to foster community and goodwill.[28][29]

On the Shabbat which falls during the week of Sukkot (or in the event when the first day of Sukkot is on Shabbat in the Land of Israel), the Book of Ecclesiastes is read during morning synagogue services in Ashkenazic communities. (Diaspora Ashkenazic communities read it the second Shabbat {eighth day} when the first day of sukkot is on Shabbat.) This Book's emphasis on the ephemeralness of life ("Vanity of vanities, all is vanity...") echoes the theme of the sukkah, while its emphasis on death reflects the time of year in which Sukkot occurs (the "autumn" of life). The penultimate verse reinforces the message that adherence to God and His Torah is the only worthwhile pursuit. (Cf. Ecclesiastes 12:13,14.)[30]

Hakhel assembly

In the days of the Temple in Jerusalem, all Israelite, and later Jewish men, women, and children on pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the festival would gather in the Temple courtyard on the first day of Chol HaMoed Sukkot to hear the Jewish king read selections from the Torah. This ceremony, which was mandated in Deuteronomy 31:10–13, was held every seven years, in the year following the Shmita (Sabbatical) year. This ceremony was discontinued after the destruction of the Temple, but it has been revived in Israel since 1952 on a smaller scale.[31]

Simchat Beit HaShoevah water-drawing celebration

During the intermediate days of Sukkot, gatherings of music and dance, known as Simchat Beit HaShoeivah (Celebration of the Place of Water-Drawing), take place. This commemorates the celebration that accompanied the drawing of the water for the water-libation on the Altar, an offering unique to Sukkot, when water was carried up the Jerusalem pilgrim road from the Pool of Siloam to the Temple in Jerusalem.[32]

Hoshana Rabbah (Great Supplication)

The seventh day of Sukkot is known as Hoshana Rabbah (Great Supplication). This day is marked by a special synagogue service in which seven circuits are made by worshippers holding their Four Species, reciting additional prayers. In addition, a bundle of five willow branches is beaten on the ground.[19]: 859 [21]

Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah

The holiday immediately following Sukkot is known as Shemini Atzeret (lit. "Eighth [Day] of Assembly"). Shemini Atzeret is usually viewed as a separate holiday.[33] In the Diaspora a second additional holiday, Simchat Torah ("Joy of the Torah"), is celebrated. In the Land of Israel, Simchat Torah is celebrated on Shemini Atzeret. On Shemini Atzeret people leave their sukkah and eat their meals inside the house. Outside the Land of Israel, many eat in the sukkah without making the blessing. The sukkah is not used on Simchat Torah.[34]

Sukkot in the generations of Israel

Jeroboam's feast

According to 1 Kings 12:32–33, King Jeroboam, first king of the rebellious northern kingdom, instituted a feast on the fifteenth day of the eighth month in imitation of the feast of Sukkot in Judah, and pilgrims went to Bethel instead of Jerusalem to make thanksgiving offerings. Jeroboam feared that continued pilgrimages from the northern kingdom to Jerusalem could lead to pressure for reunion with Judah:

If these people go up to offer sacrifices in the house of the Lord at Jerusalem, then the heart of this people will turn back to their lord, Rehoboam king of Judah, and they will kill me and go back to Rehoboam king of Judah.

Nehemiah

You can help expand this section with text translated from the corresponding article in Hebrew. (May 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Hannukah

You can help expand this section with text translated from the corresponding article in Hebrew. (May 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

In Christianity

Sukkot is celebrated by a number of Christian denominations that observe holidays from the Old Testament. These groups base this on the belief that Jesus celebrated Sukkot (see the Gospel of John 7). The holiday is celebrated according to its Hebrew calendar dates. The first mention of observing the holiday by Christian groups dates to the 17th century, among the sect of the Subbotniks in Russia.[35]

Academic views

De Moor has suggested that there are links between Sukkot and the Ugaritic New Year festival, in particular the Ugaritic custom of erecting two rows of huts built of branches on the temple roof as temporary dwelling houses for their gods.[36][37]

Some have pointed out that the original Thanksgiving holiday had many similarities with Sukkot in the Bible.[38][39]

See also

- Feast of Wine

- List of harvest festivals

- Palm Sunday

- Sukkah City – a 2010 public art and architecture competition planned for New York City's Union Square Park

- Ushpizin, 2004 film

- Shkinta

Notes

- ^ Biblical Hebrew: חַג הַסֻּכּוֹת Ḥag haSukkōṯ, lit. "the pilgrimage of booths". Also spelled Sukkoth, Succot; Ashkenazi Hebrew: Sukkōs

References

- ^ "Zmanim - Halachic Times". www.chabad.org.

- ^ a b "Sukkot | Meaning, Traditions, & Tabernacles | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ^ "Sukkot, The Feast of Booths (known to some as the Feast of Tabernacles) | Jewish Voice". www.jewishvoice.org. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ "Chabad Library". October 20, 2024.

- ^ Farber, Zev. "The Origins of Sukkot". www.thetorah.com.

- ^ a b "Booths (Tabernacles), Feast of". www.encyclopedia.com. New Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c Rubenstein, Jeffrey L. (2020). "The Origins and Ancient History of Sukkot". A History of Sukkot in the Second Temple and Rabbinic Periods. Brown Judaic Studies. pp. 13–30. doi:10.2307/j.ctvzpv502.7. ISBN 978-1-946527-28-8. JSTOR j.ctvzpv502.7. S2CID 241670598.

- ^ MacRae, George W. (1960). "The Meaning and Evolution of the Feast of Tabernacles". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 22 (3): 251–276. ISSN 0008-7912. JSTOR 43710833.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. "TABERNACLES, FEAST OF - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ Frankel, David. "How and Why Sukkot was Linked to the Exodus - TheTorah.com". www.thetorah.com.

- ^ Yoel Bin Nun, Zachor Veshamor p.168; Noga Hareuveni, Teva Venof Bemoreshet Yisrael, p.68-70

- ^ Finkelman, Shimon; Shṭain, Mosheh Dov; Lieber, Moshe (1994). Scherman, Nosson (ed.). Pesach: Its observance, Laws and Significance. Mesorah Publications. p. 88. ISBN 9780899064475. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Dr. Chaim Charles (12 October 2014). "True Chol Hamoed Celebration is only in Israel". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Shulchan Orech, Orach Chayim. 658:1.

- ^ "Building the Sukkah - Halachipedia". halachipedia.com. Retrieved 2022-10-13.

- ^ "How do we make a Sukkah?". BeingJewish.com. 20 December 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Belz, Yossi (10 September 2009). "Sukkot". ajudaica.com. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Sukkah Decoration". The Jewish Museum. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Sacks, Lord Jonathan (2009). The Koren Siddur (Nusaḥ Ashkenaz, 1st Hebrew/English ed.). Jerusalem: Koren Publishers. ISBN 9789653010673.

- ^ As they appear in Machzorim of the Ashkenazic and Italian rites.

- ^ a b "Honshana Rabbah". Chabad.org. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "ushpizin". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 19. p. 303.

- ^ Tauber, Yanki. "The Ushpizin". Chabad.

- ^ Hasit, Arie (4 October 2019). "On Ushpizin and Ushpizot: The Guests at My Sukkah". Haaretz. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Seidenberg, David (2006). "Egalitarian Ushpizin: The Ushpizata". NeoHasid.org. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayim, 530

- ^ Krakowski, Rabbi Y. Dov (10 April 2014). "Hilchos Chol HaMoed". Orthodox Union. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Pine, Dan (7 October 2011). "Community festivals celebrate Sukkot with food and fun". J. Jweekly. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Sukkot: The Festival of Booths". ReformJudaism.org. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Schlesinger, Hanan (15 September 2002). "Ecclesiastes (Kohelet)". MyJewishLearning.org. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Appel, Gershion (Fall 1959). "A Revival of the Ancient Assembly of Hakhel". Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought. 2 (1): 119–127. JSTOR 23255504.

- ^ Prero, Rabbi Yehudah (4 April 2016). "Simchas Bais HaShoeva – A Happiness of Oneness". Torah.org. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ See Rosh Hashanah 4b for rare cases where it is viewed as part of the Sukkot holiday.

- ^ "A Deeper Look at Shemini Atzeret / Simchat Torah". Chabad.org. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Understand the Feast of Tabernacles From a Christian Viewpoint". Learn Religions. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ De Moor, Johannes Cornelis (1972). New Year with Canaanites and Israelites. Kok. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Wagenaar, Jan A. (2005). Origin and Transformation of the Ancient Israelite Festival Calendar. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 156. ISBN 9783447052498.

- ^ Morel, Linda (20 November 2003). "Thanksgiving's Sukkot Roots". Jewish Journal. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Gluck, Robert (17 September 2013). "Did Sukkot Shape Thanksgiving?". Retrieved 29 September 2019.

Further reading

- Chumney, Edward (1994). The Seven Festivals of the Messiah. Treasure House. ISBN 978-1-56043-767-3.

- Howard, Kevin (1997). The Feasts of the Lord God's Prophetic Calendar from Calvary to the Kingdom. Nelson Books. ISBN 978-0-7852-7518-3.

External links

Jewish

General

- Thetorah.com - Sukkot

- Encyclopædia Britannica - Sukkot

- Jewish Encyclopedia - Sukkot

- Jewish Virtual Library – Jewish Holidays: Sukkot

- My Jewish Learning: Sukkot 101

By branch of Judaism

- Reform Judaism: Sukkot Reform Judaism

- The Rabbinical Assembly: Sukkot Conservative Judaism

- Orthodox Union – Jewish Holidays: Sukkot Orthodox Judaism

- Chabad.org: Sukkot & Simchat Torah Hasidic Judaism

- Reconstructing Judaism: Sukkot Reconstructionist Judaism

- Sukkot – Society for Humanistic Judaism Humanistic Judaism

- The Karaite Jews of America: Sukkot Karaite Judaism

Christian

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !