Kurdish Americans

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 25,000 (0.01% of U.S. population; 2020 Census figures)[1] Higher community estimates of 40,000 and beyond[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

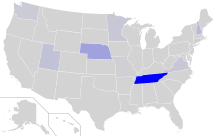

| San Diego, Nashville, Tennessee, and in the upper Midwest, including in Nebraska, Moorhead, Minnesota, and Fargo, North Dakota[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Kurdish, American English | |

| Religion | |

| Islam and Yazidism |

|

Kurds in the United States (Sorani Kurdish: کوردانی ئەمریکا) refers to people born in or residing in the United States of Kurdish origin or those considered to be ethnic Kurds.

The majority of Kurdish Americans are recent migrants from Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. Most have roots in Kurdistan Region (northern Iraq) or Iranian Kurdistan (northwestern Iran).[4] The Iraqi Kurdish people comprise the largest proportion of ethnic Kurds living in the US.

The first wave of Kurdish immigrants arrived as refugees during the 1970s as a result of the Iraqi–Kurdish conflict. A second wave of Kurdish immigrants arrived in the 1990s fleeing Saddam Hussein's genocidal Anfal Campaign in northern Iraq. The most recent wave of Kurdish immigrants arrived as a result of the 2011 Syrian Civil War and the 2014 Iraqi Civil War, including a number who worked as translators for the U.S. military.[5]

In recent years, the Internet has played a large role in mobilizing the Kurdish movement, uniting diasporic communities of Kurds around the Middle East, South East Asia, European Union, Canada, the US, and Australia.[6]

History

Kurdish immigration to the US began in the 20th century, after the World War I, with several waves of migration to the United States from the area considered Kurdistan. Following the war, the Iraqi Revolution increased the emigration of Kurds to the United States. After the war, the Kurds had been promised an autonomous region, Kurdistan in the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. The ideology of the time was heavily influenced by Woodrow Wilson's doctrine of the right to self-determination.[7]

After the Turkish War of Independence, however, the treaty was annulled and replaced with the Treaty of Lausanne, which denied any Kurdish claim to an autonomous region. After the reversal of Kurdish land claims and ensuing persecution, Kurdish emigration from the Middle East began. Many diaspora communities were established in Europe and other Kurds emigrated to the US.[8]

Following the wave of migrants that left in the aftermath of the World Wars, a second wave of Kurds in 1979 came from the north of Iraq and Iran.[7] Migration was mainly due to the Iranian Revolution in 1979. There were also large groups of Kurds that left because of the socio-political turmoil, a byproduct of the revolution and general political instability. Many of the immigrants who made the journey in 1979 had hoped to overthrow the Shah or at least opposed him. The opposition to the Shah, many immigrants from Iran were granted asylum with little trouble and received assisted travel to the US.[9] Other byproducts of the revolution were border disputes between Iran and Iraq, which culminated in the Iran–Iraq War, from 1980 to 1988.

The third distinguished wave of Kurdish migrants arrived between 1991 and 1992 and is considered to be the largest of the four waves.[7] The migration was partly due to Kurdish support for Iran in the Iran–Iraq War because Saddam Hussein had retaliated by attacking multiple Kurdish regions with chemical weapons. The most horrific and infamous of these attacks occurred at Halabja in 1988. Although different groups of Kurds have alternate interpretations of the attack, Kurds usually regard the event as evidence of genocide against the Kurdish people and have used that claim for political gains.[10] Although there was widespread support for Iran from Iraqi Kurds, the war caused severe internal divisions within the Kurdish population.[11] Thousands of Kurds then moved to the US.[12]

Another major wave of Kurdish migration to the United States or at least to Nashville, which has the largest concentration of Kurdish communities in the country, was in 1996 and 1997, following a major civil war between Iraqi Kurdistan's two major political parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The Iraqi army began targeting hundreds of individuals accused of working against Saddam's regime. The International Organization for Migration initiated an evacuation. Kurdish refugees crossed the Turkish border, after which they were evacuated to Guam, a US territory, and later resettled in the US.[13]

The collapse of Saddam Hussein's regime in April 2003 led to a massive influx of Kurds returning to lands they were displaced from during the Ba'athist policies. Several groups of Kurds emigrated to the United States by the instability caused by land disputes between returning Kurds and Arabs whose land they had occupied[12]

Demography

The total Kurdish population in the United States according to the 2000 census was 9,423.[14] More recent accounts estimate the total Kurdish population in the US at around 15,361.[15] Other sources claim that the number of ethnic Kurds in the United States is between 15,000 and 20,000 people.[16]

The city of Nashville, Tennessee includes the largest Kurdish population in the United States. A neighborhood in south Nashville has been nicknamed as "Little Kurdistan" due to its large number of Kurds.[17] Based on the 2000 census, the Kurdish population in Tennessee is 2,405, and in Nashville, the Kurdish population is 1,770.[18] According to Salahadeen Center of Nashville, there are more than 10,000 Kurds living in Nashville.[19] As of 2017, there were approximately 15,000 Kurds in Nashville out of the estimated 40,000 that reside in the entire United States. This is the largest population of Kurds in the United States. However, the U.S. Census data shows there are approximately 4,000 Kurds in Davidson County, and 5,000 in Tennessee, much lower than what Kurdish community officials estimate.[1][20] There are also sizable populations in Dallas, Texas, Atlanta, Georgia, areas of Southern California such as San Diego, Binghamton, New York, and Bridgeport, Connecticut as well as Waterbury, Connecticut.[21][22][5] Most have roots in northern Iraq or northwestern Iran.[4]

California and Tennessee, both according to U.S. Census data published in 2020, have a similar number of Kurds, hovering around 5,000. There are nearly 2,000 Kurds in San Diego County alone, and most Californian Kurds live in Southern California, with some, but significantly less of a presence in Northern California. There are 3,000 Kurds in Texas, especially within the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex area.[1]

Iraqi Kurds

Kurds in Iraq have been the subject of aggressive Arabization processes following the Al-Anfal campaign of the early 1990s. The Arabization process took place in conjunction with massive displacement of Kurdish families from Kurdish regions, leading to an influx in Kurdish immigrants during the early 1990s.[9] Iraqi Kurdish populations in America have open channels of communication with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) mediated through various groups such as cultural centers, mosques, and other humanitarian organizations. Due to this communication network, Kurdish organizations in the US have provided a significant amount of aid and humanitarian relief to the Iraqi Kurdish population on several occasions, oftentimes going through the KRG to implement relief efforts.[23]

Iranian Kurds

The most aggressive of these policies was a language policy by Reza Khan that attempted to ban the Kurdish language, in favor of Persian.[24] Despite oppressive policies such as the banning of the language, Iranian Kurds achieved semi-autonomy for a brief moment in time when the Mahabad Republic rose to power in 1945, with the tacit support of the Soviet Union.[25] The Iranian Revolution that took place in 1979 had multiple effects on Iranian Kurdish emigration because of the economic and political instability that it caused within Iran and the accompanying Kurdish persecution. The international support and attention dissenters of the shah received helped Iranian refugees receive asylum in the US, which led to a large wave of migrants following the Revolution. Kurds occupy an unclear socio-political position in Iran. Although the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran granted equal rights to all ethnic minorities, distribution of vital resources such as healthcare, education, housing, and employment indicate that Kurds in Iran have remained an oppressed group in practice.[26]

Turkish Kurds

The "Kurdish Question" has been present in Turkish politics since the country's inception l, and the issue has remained contentious. The Turkish government has tried multiple assimilation strategies, including language policies that suppressed the Kurdish language, discriminative economic and employment practices towards Kurdish people and attempting to wholly ignore the ethnic identity of Kurds by referring to them instead as "Mountain Turks".[27] There are far fewer American Kurds from Turkey than Iran and Iraq. One reason for the scarce amount of Turkish Kurds emigrating to the US is that many emigrating Turkish Kurds will travel to one of the closer Kurdish diaspora communities within the European Union like Germany, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland, all of which are all home to varying sized Kurdish communities.[28][29]

Language

Kurdish immigrants do not share a common language, however there are various dialects depending on the area of Kurdistan a Kurd is from. It has been deliberately outlawed from assimilation practices in Turkey and Iran.[30] The language is officially recognized in the Iraqi constitution, alongside Arabic. Kurdi, or Sorani, emerged as the literary expression of Kurdish language and is recognized in Iraq as the official written form of Kurdish.[31] Within the Kurdish language, there are three dialect groups: Northern Kurdish/Kurmanji (the largest group), Central Kurdish/Sorani, and Southern Kurdish/Laki. The existing linguistic divisions within the Kurdish language make it difficult to generalize about what languages are being spoken by Kurds in the United States. English is spoken much more frequently by younger generation Kurds than the older. Although an emerging phenomenon in the US, other diasporic Kurdish communities in the European Union have demonstrated that the immigration experience oftentimes leads to a dissolution of previous existing linguistic barriers, allowing for a more cohesive Kurdish community in the diaspora than was possible in Kurdistan.[32]

2020 census

List of U.S. states by Kurdish population according to the 2020 census:

| State | Numbers | % |

|---|---|---|

| 4,850 | 18.7% | |

| 3,467 | 13.37% | |

| 2,931 | 11.3% | |

| 2,566 | 9.9% | |

| 1,068 | 4.12% | |

| 906 | 3.49% | |

| 836 | 3.22% | |

| 761 | 2.93% | |

| 720 | 2.78% | |

| 709 | 2.73% | |

| 636 | 2.45% | |

| 579 | 2.23% | |

| 484 | 1.87% | |

| 470 | 1.81% | |

| 441 | 1.7% | |

| 425 | 1.64% | |

| 417 | 1.61% | |

| 381 | 1.47% | |

| 369 | 1.42% | |

| 328 | 1.26% | |

| 290 | 1.12% | |

| 283 | 1.09% | |

| 272 | 1.05% | |

| 203 | 0.78% | |

| 159 | 0.61% | |

| 157 | 0.61% | |

| 103 | 0.4% | |

| 102 | 0.39% | |

| 95 | 0.37% | |

| 93 | 0.36% | |

| 88 | 0.34% | |

| 87 | 0.34% | |

| 75 | 0.29% | |

| 72 | 0.28% | |

| 57 | 0.22% | |

| 53 | 0.2% | |

| 53 | 0.2% | |

| 53 | 0.2% | |

| 40 | 0.15% | |

| 40 | 0.15% | |

| 35 | 0.13% | |

| 32 | 0.12% | |

| 27 | 0.1% | |

| 26 | 0.1% | |

| 21 | 0.08% | |

| 18 | 0.07% | |

| 17 | 0.07% | |

| 11 | 0.04% | |

| 11 | 0.04% | |

| 5 | 0.02% | |

| 4 | 0.02% | |

| 3 | 0.01% | |

| Total | 25,929 | 100% |

Notable people

- Hamdi Ulukaya, Businessman and entrepreneur, founder of Chobani

- Herro Mustafa, US Diplomat

- Najmiddin Karim, Politician and Neurosurgeon

- Azad Bonni, Neuroscientist at Washington University School of Medicine

- Jano Rosebiani, Filmmaker

- Hakki Akdeniz, Philanthropist and restaurateur. Owner and founder of the pizzeria chain Champion Pizza and Hakki's in New York City

- Saad Abbas Ismail, Archaeologist, translator and writer

- John Shahidi, Businessman, manager and President of Shots Podcast Network, Nelk Boys and Happy Dad Hard Seltzer

- Sam Shahidi, Co-founder of Shots Podcast Network and CEO of Happy Dad Hard Seltzer

- Amar Suloev, mixed martial artist. Fought for the UFC, PRIDE Fighting Championships, Cage Rage, and M-1 Global

- Naren Briar, human rights activists.[34]

- Karzan Kardozi, filmmaker known for Where Is Gilgamesh?.[35]

- Edip Yüksel, Islamic philosopher and intellectual, considered one of the prime figures in the modern Islamic reform and Quranism movements

- Jamal al Barzinji, Businessman, associated with the International Institute of Islamic Thought, the World Assembly of Muslim Youth, and the SAAR Foundation

- Hanna Jaff, Activist

- Haidar Khezri, A Professor of Kurdish and Middle Eastern Studies at University of Central Florida.

- Gazi Zibari, Director of Transplantation Services and Advanced Surgery Center, in Shreveport, Louisiana.

- Hayman Homer, actor known for The Messiah.[36]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Total Population – Census Bureau Table".

- ^ "The Kurdish Diaspora". Institutkurde.org. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ The Kurds: An Encyclopedia of Life, Culture, and Society. p. 308.

- ^ a b "Immigrants thrive in US country music capital". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Sawyer, Ariana Maia (June 23, 2017). "Who are the Kurds, and why are they in Nashville?". The Tennessean. Gannett Company. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Yeğen, Mesut (2008). "Review: The Kurdish Nationalist Movement: Opportunity, Mobilization and Identity". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 40 (3): 518–520. doi:10.1017/S0020743808081245. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 40205989. S2CID 162907844. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c Ryan, David, and Patrick Kiely. America and Iraq: Policy-making, Intervention and Regional Politics. London: Routledge, 2009.

- ^ Baser, Dr Bahar. Diasporas and Homeland Conflicts: A Comparative Perspective. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2015.

- ^ a b Mansfield, Peter, and Nicolas Pelham. A History of the Middle East. London: Penguin, 2013.

- ^ Watts, N. F. (January 1, 2012). "The Role of Symbolic Capital in Protest: State-Society Relations and the Destruction of the Halabja Martyrs Monument in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 32 (1): 70–85. doi:10.1215/1089201X-1545327. ISSN 1089-201X.

- ^ Yildiz, Kerim, and Tanyel B. Tayşi. "Iranian State Policy and the Kurds: Politics and Human Rights." The Kurds in Iran: The Past, Present and Future. London: Pluto, 2007. N. pag. Ebsco Host. Web.

- ^ a b Yildiz, Kerim. The Kurds in Iraq: The Past, Present and Future. London: Pluto, 2007.

- ^ UC Davis. "Kurds and Refugees – Migration News | Migration Dialogue." Migration News. University of California Davis, n.d. Web. 8 April 2015.

- ^ US Census Bureau. "The Arab Population: 2000" (PDF). Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ^ "2006–2010 American Community Survey Selected Population Tables". Government of the United States of America. Government of the United States of America. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "The Kurdish Diaspora". Institutkurde.org.

- ^ "Nashville's new nickname: 'Little Kurdistan'". The Washington Times. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Patricia, De La Cruz G., and Angela Brittingham. The Arab Population, 2000. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau, 2003.

- ^ "Salahadeen Center Of Nashville." SCN History. Salahadeen Center Of Nashville, n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

- ^ Eccarius-Kelly, Vera (Winter 2018). "The Kurdistan Referendum: An Evaluation of the Kurdistan Lobby". Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. 41 (2): 16–37. doi:10.1353/jsa.2018.0012.

- ^ Chedekel, Lisa (January 28, 2005). "Kurds in State Travel Far to Vote". courant.com.

- ^ Manfield, Lucas (November 11, 2019). "Silent No Longer: Trump's Betrayal Stirs DFW's Sizable Kurdish Community to Action". Dallas Observer.

- ^ Nashville, Tony Gonzalez The Tennessean. "Nashville Kurds Rally to Aid Families in Conflict." USA Today. 1 Sept. 2014. Web. 2 Mar. 2015.

- ^ SHEYHOLISLAMI, Jaffer (2012). "Kurdish in Iran: A case of restricted and controlled tolerance". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (217): 19–47. ISSN 0165-2516. Retrieved February 25, 2021 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Roosevelt, Archie Jr. (1947). "The Kurdish Republic of Mahabad". Middle East Journal. 1 (3): 247–269. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4321887. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Gunter, Michael M. Out of Nowhere: The Kurds of Syria in Peace and War. N.p.: Oxford UP, 2014.

- ^ ZEYDANLIOGLU, Welat (2012). "Turkey's Kurdish language policy". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (217): 99–125. ISSN 0165-2516. Retrieved March 18, 2015 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Wahlbeck, Östen (June 1, 2012). "The Kurdish Refugee Diaspora in Finland". Diaspora Studies. 5 (1): 44–57. doi:10.1080/09739572.2013.764124. ISSN 0973-9572. S2CID 153877727. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Baser, Bahar. Diasporas and Homeland Conflicts: A Comparative Perspective. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2015.

- ^ Hardach, Sophie (2013). ""'Professor, You're Dividing My Nation'; In Iraqi Kurdistan, tongues are tied by politics."". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 59 (41). Retrieved March 20, 2015 – via Academic OneFile.

- ^ Haddadian-Moghaddam, Esmaeil; Meylaerts, Reine (2014). "What about Translation? Beyond "Persianization" as the Language Policy in Iran". Iranian Studies. 48 (6): 851–870. doi:10.1080/00210862.2014.913437. ISSN 0021-0862. S2CID 144199492. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Schmidinger, Thomas. "The Kurdish Diaspora in Austria and Its Imagined Kurdistan." The Kurdish Diaspora in Austria and Its Imagined Kurdistan (n.d.): n. pag. Kurdipedia. Web.

- ^ "Census Bureau Data". Retrieved October 20, 2024.

- ^ "Naren Briar Washington Kurdish Institute". Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ "Karzan Kardozi IMDB". Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ "Hayman Homer IMDB". Retrieved September 12, 2024.

Further reading

- Dundas, Chad (2014). "Kurdish Americans". In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America. Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). Gale. pp. 41–52.

- Meho, Lokman I., ed. The Kurdish Question in U.S. Foreign Policy: A Documentary Sourcebook (Praeger, 2004).

- O'Connor, Karen. A Kurdish Family: Journey Between Two Worlds (Lerner Publishing Group, 1996).

- Sheyholislami, Jaffer; Sharifi, Amir (January 1, 2016). ""It is the hardest to keep": Kurdish as a heritage language in the United States". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2016 (237): 75–98. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2015-0036. ISSN 1613-3668. S2CID 151708039.

See what we do next...

OR

By submitting your email or phone number, you're giving mschf permission to send you email and/or recurring marketing texts. Data rates may apply. Text stop to cancel, help for help.

Success: You're subscribed now !